The History of Parkway Gardens, a Bucolic Haven for Middle-Class Black Families

A fleet of limousines pulled into the cul-de-sac in front of photographer Gordon Parks’s bungalow at 15 Adams Place in the suburban enclave of Parkway Gardens, in Greenburgh, New York. Groups of African-Americans, dressed in their summer finery, emerged from the late model limos. It “looked like a car salesman’s paradise,” socialite Betty Granger wrote in her Amsterdam News column, “Conversation Piece.” It was September 12, 1954, and Parks, who was finding acclaim as a photo-journalist and a top-paid Vogue fashion photographer, had invited nearly 50 friends for a party around his new in-ground pool.

Few homeowners of any race had in-ground pools in the 1950s. And most African-Americans had for years been denied access to the nicer park and hotel pools on account of Jim Crow segregation laws. The temperature that day reached only 72 degrees, but many braved a chilly dip simply for novelty’s sake. According to Granger’s firsthand account, six uniformed servers weaved around the -Parkses’ well-manicured lawn, serving lounging guests “100 pounds of barbecued chicken and ribs” and “12 cases” of vintage champagne.

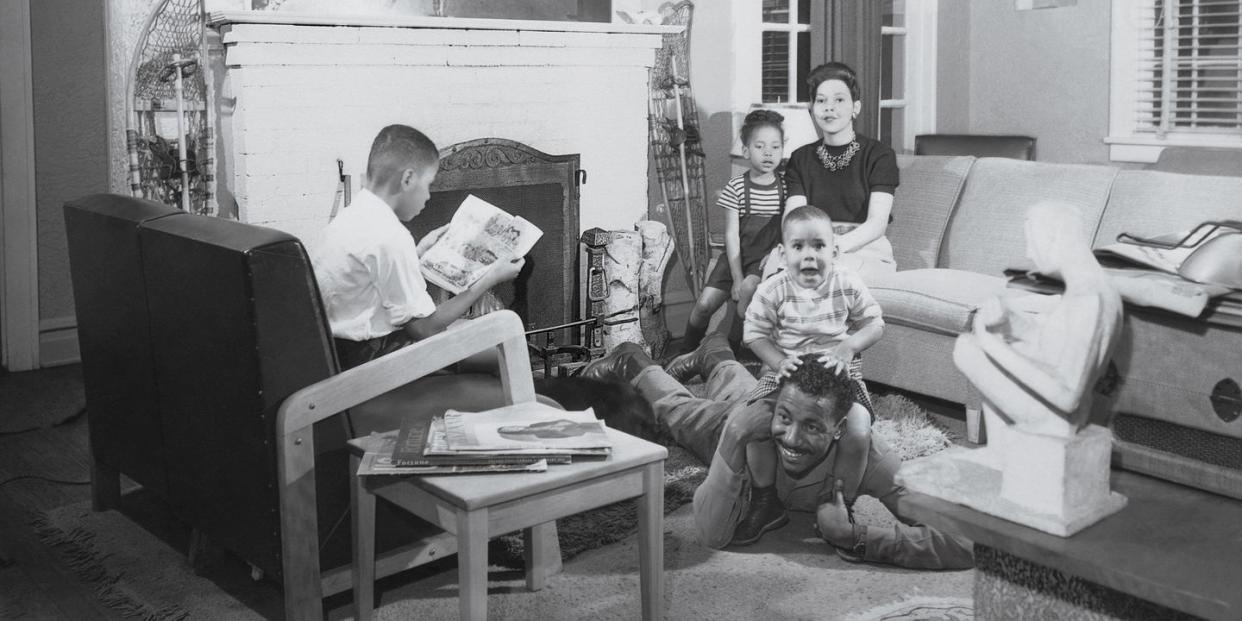

The party raged until midnight, and not one of Parks’s mostly Black neighbors called the police to complain. This was the type of safety and community that Gordon and his wife Sally had sought when they decided to move their family of five from a cramped apartment in Harlem to Greenburgh nearly a decade earlier—when the area was still mostly white. “I desperately wanted the children to escape the hardships I had endured,” Parks wrote in his 2005 memoir, A Hungry Heart. “The bungalow I found was surrounded by space, trees, and a lawn.” He was not alone in this desire. Hundreds of thousands of African-Americans across the country braved the move to suburbs like Greenburgh in the 1940s and ’50s.

I visited Parkway Gardens recently, lured by the description of a suburban paradise that unfolds in Parks’s memoir. I was surprised to find no sign of its former grandeur—no marker of the important role it played in African-American history. In fact, it looked like many other neighborhoods whose architectural charm has been dulled by aluminum siding and overdevelopment. I stopped a group of passersby, and they nodded when I brought up Parkway Gardens’ past. And then, as it so often does, the conversation turned to the neighborhood’s shifting demographics—a result of recent gentrification—and how difficult it can be to preserve the past.

Parks’s home, now a registered town landmark, remains unchanged, and it offered me a rare glimpse of a forgotten time when dreams of freedom, World War II–era financial opportunities, and the rise of conspicuous consumption collided, making Parkway Gardens a premier destination for upwardly mobile African-Americans.

There has been a Black presence in Greenburgh since enslavement, but the town, located in Westchester County west of White Plains, began to take shape as a suburban refuge for Blacks at the close of the 1920s. Its earliest Black residents were migrants from the South and the Caribbean who found work as manual laborers and domestics. They settled on large, inexpensive plots of land, built their own homes, and raised livestock—before there were streetlights, paved roads, or a real sewage system in Greenburgh.

Town developers established Parkway Gardens and the adjacent Parkway Homes in 1925 (following the completion of the Bronx River Parkway) as a haven for ambitious Italian and Irish immigrants. The prices of the houses were prohibitive for most African--Americans until the stock market crash of 1929, when real estate values plummeted. Financial turmoil proved fortuitous for the few African--Americans who had been able to protect their nest eggs as the nation spiraled into the deepest depression in its history. That year Anna Bernard, a New York University Law School graduate, and her dentist husband, Woodruff Robinson, were able to purchase a home at 191 South Road in Parkway Gardens. As most of their Black peers in places like Harlem bore the brunt of the Great Depression’s effects, the Bernards and other Blacks of various socio-economic classes in neighboring communities formed garden clubs and opened beauty salons and barbershops, churches, restaurants, and nightspots, which slowly transformed the landscape of southwestern Westchester County.

Falling prices helped, but it was prominent socialite--journalists like Betty Granger and Dorris McNeil—who would launch her weekly Amsterdam News column “Westchester Notes” in the early 1950s—who helped make the suburbs a destination for New York’s Black high society. Granger and McNeil penned pieces about splashy sorority and fraternity garden parties, and tournaments hosted by bridge clubs with French names like Parmi Nous (among us) and Les Jolie Huit (The Pretty Eight). They amplified the philanthropic work of social clubs like the Pearls of Westchester. And they offered a view into the world of exclusive Black civic organizations and secret societies such as the Boule and the Links, Incorporated.

The columnists were putting names, faces, and places to a dream that had long been denied African-Americans. Every account of spacious back yards, lively social calendars, proximity to beaches and ski resorts, and easy access to commuter trains to New York City made suburban homeownership look appealing.

“Parkway Gardens was central to entertainment for Black society,” says Ken Jones, a Greenburgh councilman and Anna Bernard’s great-nephew. “A lot of celebrities lived here, and there were fabulous parties.” After Parks’s arrival, a string of other Black celebrities moved to or near Parkway Gardens in the 1950s. Jazzman Cab Calloway purchased a 12-room home on Knollwood Road, where he hosted legendary poker parties. Comedian “Moms” Mabley had a home on North Road. Jazz pianist Hazel Scott, the wife of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., lived on South Road, near retired Brooklyn Dodger star Roy Campanella. Diana Sands, an actress who had been in the original production of Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun, which examined the challenges of Black homeownership, lived on Van Buren Place.

But along with pool parties and garden soirees lurked the real threat of anti-Black violence. In 1937 businessman Philip Jenkins bought a house in the community, and when he and his wife drove up from Harlem to their new home, they were met by “five cars filled with men [who] surrounded the house,” Jenkins recalled in a 1987 article in the Greenburgh Inquirer. The men tried to block them from moving in, Jenkins said, because they believed “Negroes and whites can’t live in the same community.” Many of his new white neighbors, he learned, held racist fears that “Negroes spread syphilis” and would make the community unsafe for white women and children. Riley Wentzler and Felicia Barber, authors of an online oral history titled Formed by Adversity, Held Together by Faith: The History of Parkway Homes/Parkway Gardens, describe other examples of how anti-Black violence in the neighborhood intensified in the 1940s and ’50s, a terror campaign that included threatening phone calls, the vandalization of property, and even burning crosses on lawns.

But the Jenkinses and many other Black newcomers were not deterred. “African-American families were not seeking to acquire homes outside of Black, urban housing markets to immerse themselves in a sea of whiteness,” says Andrew Kahrl, professor of history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. “They were seeking to escape from the clutches of predatory conditions within their own neighborhoods.”

Soon developers like the Manhattan-based Alanwood Corporation saw an opportunity to capitalize on Westchester’s rising popularity. It built more than 1,000 single-family homes across the county between 1945 and 1956, with 59 in Parkway Gardens alone. But as African--American strivers moved into the new Parkway Gardens homes, many whites fled to other neighborhoods. This simultaneous migration—along with vestiges of redlining and restrictive covenants that dated back to the 19th century—created a valuation dynamic that continues to this day. “The cost of homes [in Parkway Gardens] still isn’t quite as high as in some of the surrounding white neighborhoods,” Jones says.

Real estate discrimination and exploitation in Greenburgh neighborhoods mirrored national trends. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, public policy expert Richard Rothstein writes, “Until the last quarter of the 20th century, racially explicit policies of federal, state, and local governments defined where whites and African-Americans should live.” Across the country, real estate investors, developers, and brokers made millions using these policies to exploit Black would-be homeowners, charging exorbitant fees, supposedly to strike restrictive covenants from deeds, while offering them predatory loans—if they granted loans at all—and undervaluing their properties. According to Rothstein, such practices were difficult for plaintiffs to prove in court because, in most cases, these schemes did not technically violate the law.

By the time Gordon Parks sold his Adams Place bungalow, in the mid-1970s, Parkway Gardens and Parkway Homes had become an affluent African-American enclave on par with other historically Black leisure communities, such as Sag Harbor on Long Island and Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard. The streets were narrower and the homes much closer together than when Parks moved in three decades earlier. But it remained what many describe as a “tight-knit” community for working-, middle-, and upper-middle-class Blacks. And its strong civic associations “give the area a certain gravitas, particularly with town government,” says Jones, who is a third--generation Parkway Gardens homeowner. “It’s very unique…to find areas that haven’t been burned to the ground, where third and fourth generations of African-Americans have lived and raised their kids in successive generations.”

As I made my way onto Parks’s old street on that late spring day, I thought of something Kahrl had said: “It is important to recognize and to preserve the history of African-Americans striving toward acquiring, enjoying, and accessing nature—spaces associated with a good life.” Then I spotted several cars with Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority license plates. A group of African-American women carrying casserole dishes and balloons in the historically Black sorority’s signature pink and green colors approached a house on the corner, where guests were mingling in the fenced back yard. It was a heartening sight, a reminder that, despite the area’s fraught history, the “good life” vibe that Parks had sought in the 1940s was still alive in Parkway Gardens.

You Might Also Like