How a New Generation of Women Painters Is Creating Dreamy Kaleidoscopic Works

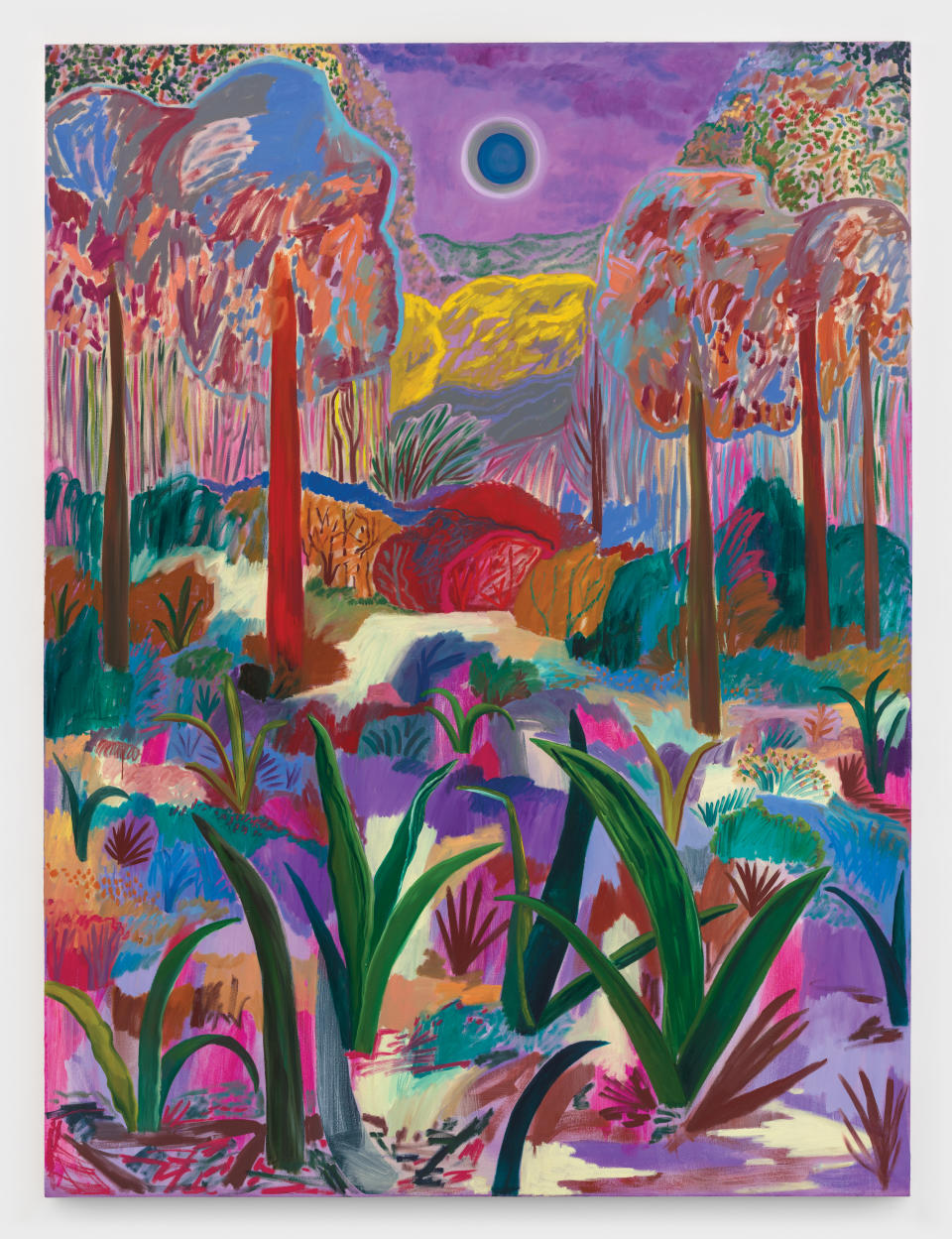

The new seascapes and landscapes in Amy Lincoln’s cozy studio, a skylighted converted garage behind her house on a quiet street in Queens, N.Y., burst with blues and magentas so vibrant, yellows and reds so brilliant, they’d make fireworks jealous. There are pink raindrops, green clouds and purple earth, lit by sunrays beaming down or radiating outward in concentric circles. The paintings, destined for a solo show opening at Sperone Westwater in New York this month, practically glow, as if illuminated on a giant iPhone.

For Lincoln, that’s no coincidence. Since creating a website for her art in the early 2000s, she has aimed to replicate on canvas the way pigment can light up digitally. “I remember thinking, ‘I want the color in the painting to be as bright in real life as it looks on the screen,’ ” she says on a gray winter morning. “Because for a little while, it looked better on-screen than in person.”

More from Robb Report

Ukraine Unveils a New Banksy Postage Stamp That Mocks Russian President Vladimir Putin

Micheal Jordan Wore These 6 Air Jordans During the NBA Finals. Now They're up for Grabs.

A Lucian Freud Painting of His Daughter Could Fetch up to $24 Million at Auction

Coupled with a reductive, almost facile style—poofy clouds and curvy waves, all perfectly symmetrical—the effect is psychedelic, or perhaps akin to Disney animation, an early influence when Lincoln was growing up in Portland, Ore. “I want them to be worlds and to be distinct from our world,” she says. “Weird” shades that “push each other around” are the goal. “I try to steer clear of the color being too obvious.”

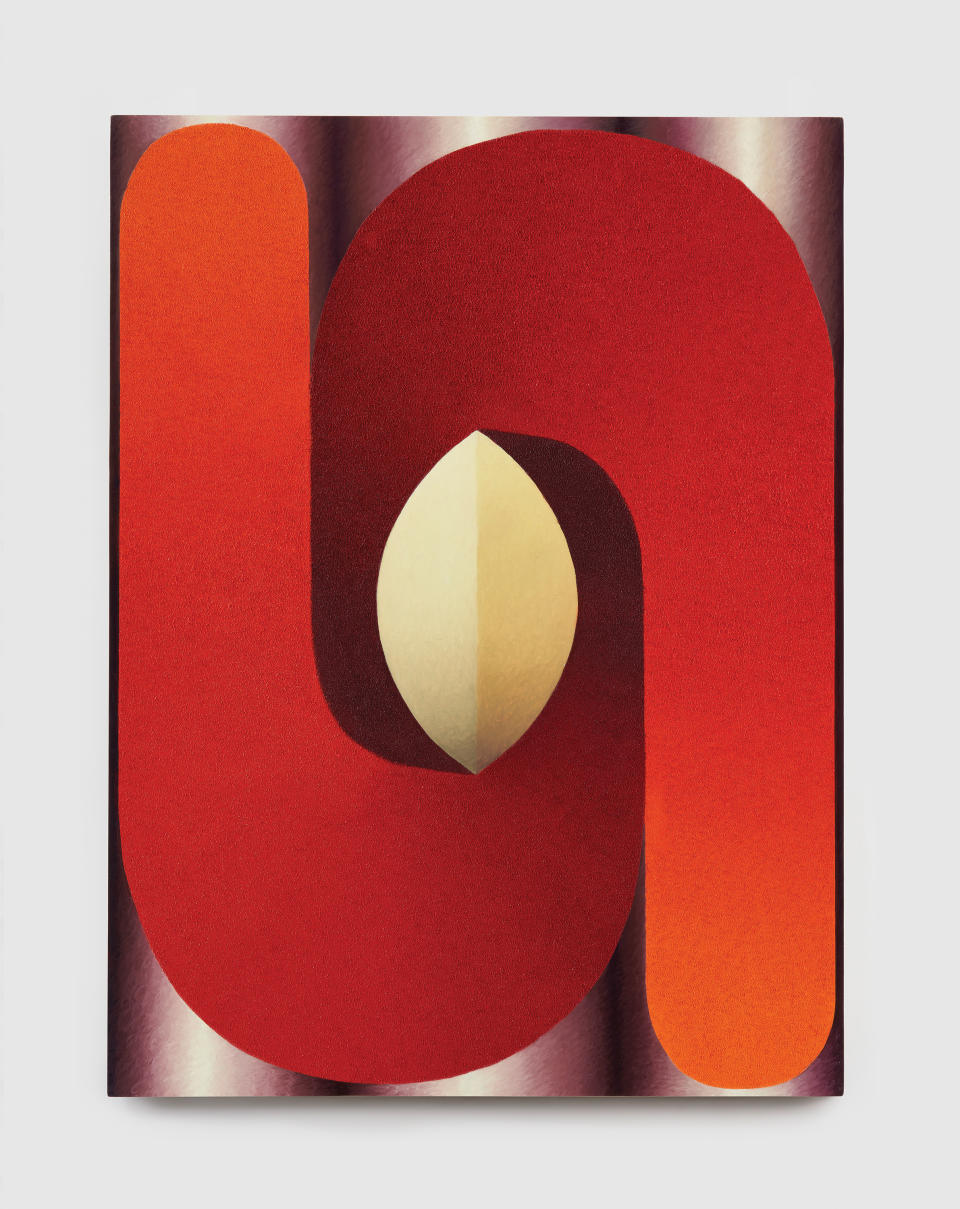

Lincoln’s dreamscapes align with the work of several other millennial women capturing the attention of collectors today, including Loie Hollowell, Lumin Wakoa, Shara Hughes and Lucy Bull. Their subjects and degrees of abstraction may vary, but they share a devotion to “color as content,” as Hollowell puts it, and a trippy vibe that gives their work an otherworldly quality. Hollowell’s recent pieces meld neo-tantric influences and references to the body into a geometric, feminist abstraction; Wakoa, meanwhile, composes impressionistic views of her garden. Hughes makes moody, dramatic landscapes, and Bull creates densely vivid canvases that look as if a flower shop exploded.

The output from these women once may have been derided as “decorative”—not long ago, “colorist” was a dirty word. But demand for their work reflects a generational shift; like Lincoln’s, these canvases look stellar online. “I definitely think of my work as operating on Instagram as much as in the real world,” Lincoln says. “That is such an important way that I interact with people. It almost feels like it’s a parallel art world, like the real art world is on Instagram, and IRL is a weird shadow of it.”

Lincoln, Hollowell and Wakoa are also close friends who live near each other, have young children of about the same ages and frequently discuss art-making. Lincoln has known Hollowell since studying under her father, artist David Hollowell, at UC Davis. “She was making these beautiful portraits of herself and of her friends,” says Loie Hollowell, who was in high school at the time. “They were just so good that I really idolized her.”

When both ended up in New York about 15 years ago, the two reconnected and developed a rapport that allowed for cross-fertilization in a period, as Lincoln recalls, when painting, especially the realism she then favored, was uncool. “Installations were big,” she says. “I think of it as a bunch-of-shit-in-a-room kind of installations, like a bunch of random garbage. A lot of what you saw in galleries was just visually dry.”

Still, Lincoln realized her own paintings had felt “out of step” since college, when she had a rude awakening. “Nobody cares that you can draw a dog that looks like a dog. What matters are your ideas,” she says. “I was working in this stodgy way, and I needed to make it contemporary.” Shaking up her practice, she abandoned painting precise nudes and self-portraits from life and experimented with drawing from memory in Sharpie and overlaying acrylic. She also ditched oil paint because she found it muddied her hues and reinforced her perfectionist tendencies. Fast-drying acrylic allowed for a looser gesture and fed her growing interest in color.

Though her work wasn’t selling much, Lincoln helped create a community. She and her now-husband, Kevin Curran, mounted exhibitions in their loft—they called it the Laundromat—to promote other artists, including Hollowell. Both women began to explore landscapes and had a two-person show in Queens in 2013. Lincoln’s images of foliage were bright and lush, reminiscent of Henri Rousseau, while Hollowell’s skewed darker. By 2019, when Lincoln began making seascapes, she had simplified her style to a minimalism that reads almost like shorthand. “It’s a symbol of a cloud or a symbol of a wave,” she says.

Nature also provided Lincoln with a less politically charged subject than portraiture, a genre that now invites scrutiny of who is—or is not—depicted. “Obviously, I am aware of climate change, but I don’t necessarily want my work to be super didactic, like warning of the hellscape that we’re all barreling toward,” she says, adding that she needs her studio practice to be more Zen.

“It’s not a catharsis of negative emotions. It’s more of a meditative, peaceful experience that I’m seeking.”

Lincoln thrived during the pandemic. She had been spending four days a week commuting to her bookkeeping clients—her longtime survival job—but, forced to stay home, she was able to condense the workload to three days. Then, with galleries resorting to posting exhibitions on their websites, her online show of seascapes with Taymour Grahne Projects in early 2021 gave her unprecedented exposure. “That was a big turning point,” she says, “because that was the first time I ever sold out a show. Things changed really quickly.”

Sperone Westwater, perhaps best known for representing conceptual-art icon Bruce Nauman, soon signed Lincoln, and by fall of that year, she was able to give up bookkeeping—as well as painting in the middle of the night—for good. In addition to no longer being able to blame a bad mood on lack of studio time, she says market success has brought its own set of worries: “Are people going to like the new work? What if I don’t want to keep making this work that everybody likes? If I try something different, will people not respond to it? Most of the problems—I should be knocking on wood—are great problems. I need to figure out how to chill out.”

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.