Franc Roddam: ‘I had the idea for MasterChef after Mel Brooks mocked British food’

It began as a retort to Mel Brooks. It was the early 1980s and a 40-something British film director from the North East was trying to hold his own in a production meeting at 20th Century Fox in Los Angeles.

“Mel Brooks and his buddies were doing their usual level best to mock British food,” recalls Franc Roddam. “They were a braying pack of creatives saying that there was no such thing as British cuisine, that if you wanted a good meal in London you had to go Italian or French or Indian. But never British.

“I tried to defend it. I said that, yes, there were instances of overcooked vegetables, but if you wanted good cooking you would find it in people’s homes.”

Brooks and co were not convinced; Roddam lost the argument. But the conversation set him thinking. He was an ambitious director with triumphs under his belt. The success of the 1979 movie Quadrophenia – which he co-wrote and directed – and his creation of the hit British show Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, among others, had given him access to big players in Hollywood. Senior executives at the BBC would take his calls.

The idea that Britain was a nation filled with great, but unknown, home cooks set him on a path to create a show that aired just a few years after that LA meeting – MasterChef. It is today watched by 300 million people worldwide, with 60 productions – all with different formats – across the globe. And as MasterChef UK, now featuring presenters Gregg Wallace and John Torode, approaches its 20th anniversary, Franc Roddam has agreed to give a rare interview.

Having been a critic on MasterChef for some 18 years, I’m fascinated to meet the man behind the show that has become not only an important part of my life, but embedded in the nation’s TV schedules.

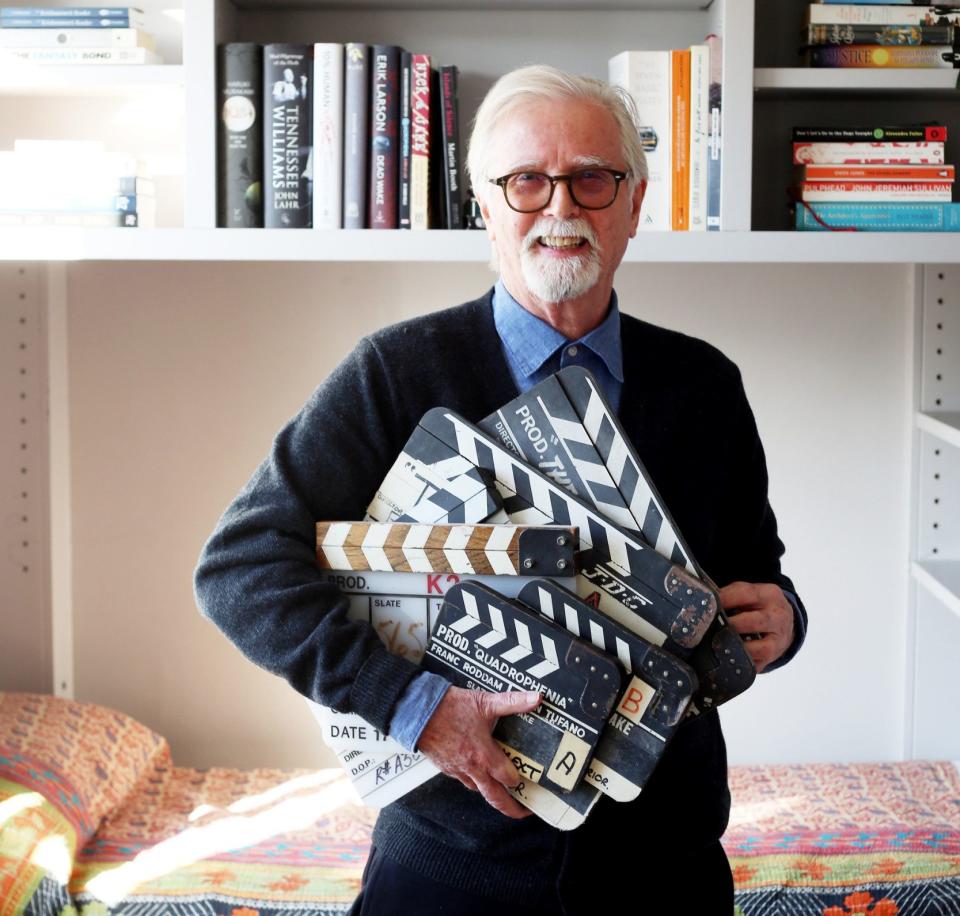

Roddam is a sprightly, fit 77-year-old and we meet in his penthouse office in Notting Hill. At a long table covered with books, he’s just checking the ratings of a Christmas special of the UK show, MasterChef: Battle of the Critics, in which I featured. “We had 2.5 million viewers, we’ll get about another million online and we won the slot,” he says with some satisfaction.

I describe the extreme pressure I experienced having my cooking efforts scrutinised. “I know what it’s like to go on the show,” he says. “I once appeared on Spanish MasterChef and it was very, very intense. I was able to appreciate the courage that people have going on it.”

But he was also on the show with the renowned and influential chef Ferran Adrià. “I said to Ferran, ‘you’ve done so much for food around the world’. And he replied, ‘but MasterChef has done more’. I’ve never forgotten that.”

Roddam attacked his initial pitching meetings to the BBC with great confidence. “I’m one of those people for whom an idea comes totally in one go. My job is to convince people to do it. And when I spoke to the BBC I had it carefully planned. I’m very contract-savvy. Everything was written down to ensure ownership. I’d been cheated too many times in the past.” The final meeting was at the BBC studios in Elstree. “They gave us a whole series and then an ensuing 14 years. Luck,” he later adds, “is an important element to my life.”

The show launched in an era of TV in which, Roddam says, “the public were separated. What MasterChef did was to create public participation rather than mere passive watching. Today the whole landscape of TV is about the public and voting. MasterChef was one of the first shows to do that.” A regular face on daytime television, Loyd Grossman, was selected as host: “Quite the foodie,” Roddam recalls, and someone he felt had the “Marmite effect, [who would] create a dialogue about the show”. Scallops and syllabub starred in gourmet three-course menus cooked by home cooks with a budget of £30.

But by the end of the 1990s the show had lost its way and, Roddam admits, “it lay fallow for a couple of years”. In the early 2000s Roddam pitched a new format to the BBC and, crucially, chose to work with Elisabeth Murdoch and her production company Shine. “She was fabulous,” he recalls. There was a new format (the celebrity judge dropped; a shorter cooking time) but there was another key difference. “MasterChef in the old format had never sold rights to the rest of the world.” Now they would sell those rights and do it ruthlessly.

Twenty years on and those rights are still agreed with Roddam, who enforces a style guide and his one key rule: “We don’t criticise people on MasterChef, only the food.”

All the global formats use the same swirling logo that Roddam created but are very different, according to the local culture. “In Brazil the show is three hours long,” he says. “In Dubai it’s a restaurant; in Los Angeles it’s a show hosted by Gordon Ramsay that’s linked to Florida where there’s a MasterChef cruise ship. In India, as the titles roll, some guy jumps out of a helicopter with a large knife which he chucks at the camera. We keep a tight hold over it all, although it’s very important that each production company feels they are making the show. Surprisingly, there is very little litigation.”

Meanwhile in the UK, from this summer, filming for MasterChef will move to a new bespoke set in Birmingham as part of the BBC’s drive to improve its regional reach. “While it’s understandable it’s also disruptive and expensive,” he says. But the reward is a renewed BBC contract for six years of UK shows in its three series formats (amateur, professional and celebrity). Roddam has also benefited from a recent trend of what TV execs call “stripping” (running episodes at the same time every day), further entrenching MasterChef into the nation’s psyche. “The show expanded to being broadcast five nights a week. That expansion served us well.”

Or as Gregg Wallace once put it, “The only problem Franc has is counting his money.” When I ask Roddam about this he says, with a twinkle: “I’m comfortable.” Comfortable enough to have a large townhouse and nearby offices in Notting Hill, and to look after the seven children he has from three marriages. And a great deal more comfortable than he was growing up in Norton-on-Tees, near Middlesbrough, where, one of seven children, his first taste of work was at the docks.

“It was an industrial town – my father was employed at the steelworks – but our patch felt more like a village. We had a large veg garden and chickens, my mother was a fabulous cook – there were always stews and cakes and lemon meringues and apple pies – and opposite us was a duck pond and a blacksmith,” he recalls. “But we also had two cinemas at the top of the street.”

That cinema gave Roddam an idea and an ambition. “I wanted to be like the stars on the screen, but a hero in my own life. So I got out of Norton in the late Sixties and started travelling, as a beatnik. I went through Turkey and Afghanistan and then eventually returned to London and joined the London Film School in Covent Garden.”

After working in movies for several years, his directing debut was with Quadrophenia in 1979, a film loosely based on The Who’s rock opera of 1973. It remains on The New York Times’s list of best movies ever made.

The film bug has never left Roddam. “I still write screenplays,” he says. “In fact I make films in my head all day. It’s cheaper and the films are perfect.”

Of his own culinary tastes, he cooks often for his large family and dines out frequently – “I’m an epicurean rather than a hedonist” – and he loves restaurants. “I like a tablecloth and a napkin.”

As to the future of his culinary creation, he still has big ideas. Very big ideas. “We are an enormous brand without a product,” he says, “and so I want MasterChef to become the biggest online supermarket in the world.” And while his BBC contract wouldn’t allow such commercial propositions, “with 300 million MasterChef viewers in the rest of the world, that’s OK”. He tells me later he’s currently nudging some Italian billionaires about the project.

With Roddam’s proven knack for selling, this episode of MasterChef will be well worth watching.