Football fans and blood balloons: how Aaron Sorkin recreated the 1968 Chicago riots

The most dramatic moments in Aaron Sorkin’s new film, which covers the trial of the leaders of the anti-war protests outside the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, were always going to be the flashbacks.

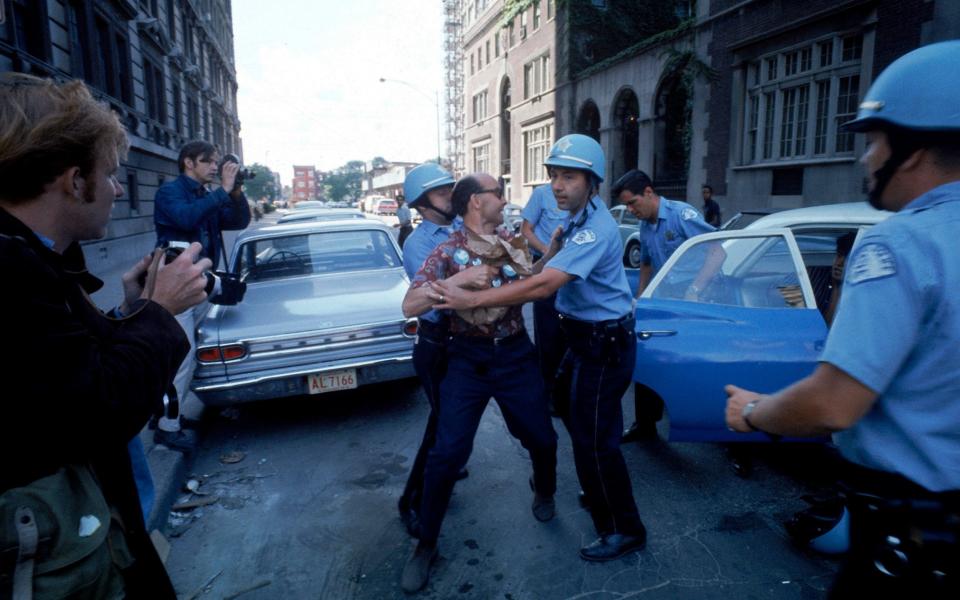

These plunge the audience back into the protests themselves, in which protesters clashed with riot police and the city descended into violence. But when Sorkin, his cast and crew went to Chicago to shoot the scenes last year, they had no idea how powerful the political turmoil of 2020 would render them by the time of the film’s release.

“It’s still going on – life hasn’t changed,” the film’s producer, Stuart Besser, tells me over the phone from the States. “That’s the thing that’s so moving to me, and so sad.

“Everything that’s out there today was there then," says Besser, pointing out that much like their 2020 counterparts, the 1968 protesters carried signs demanding women's rights and civil rights. "When you see it still happening, as a parent it’s like, ‘When will we get it? When will this be right?’”

The Trial of the Chicago 7, which is on Netflix now, arrives after a year in which Black Lives Matter protests, triggered by the police killing of George Floyd in May, have swept America and the world.

Besser reflects: “Seeing black people being beaten for walking over a bridge in Alabama [during the Selma to Montgomery protest marches in 1965], then in 1968 seeing them be beaten in a park for their political views, and now seeing them being beaten again for a different point of view… it’s so troubling.”

The film moves backwards in time, beginning in 1969 when the seven leaders of the protests (as well Black Panther leader Bobby Seale) were put on trial, charged with conspiracy to cross state lines to incite riots. The actual riot scenes come late in the film, emerging via flashbacks as the trial unfolds, and the prosecution and defence tussle over conflicting narratives about what actually happened over that fateful week.

But in production, the Chicago scenes were the first to be filmed, over a freezing cold, speedy nine-day shoot in October 2019.

“We were a pretty brazen group of filmmakers,” Besser laughs. “Talk about jumping in the pool and seeing who can swim!”

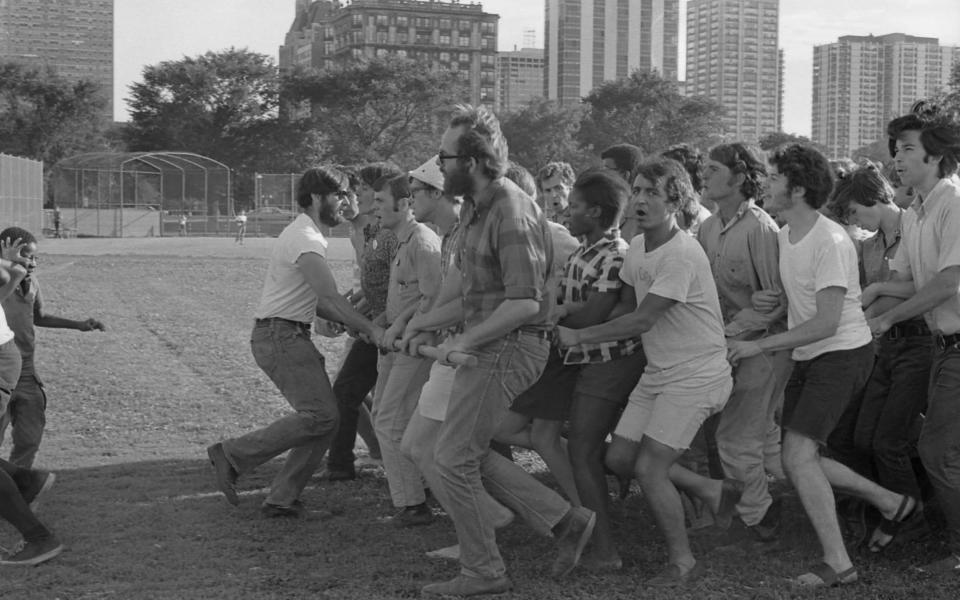

They had the backing of the city government, but ran up against a few unexpected obstacles. The first problem: it was football season. The most prominent locations were Lincoln Park, where the protesters set up camp during the Convention and which became the site of the worst police violence, and Michigan Avenue, one of the major thoroughfares through the city. Besser and Sorkin had planned to shoot in both places on Sunday, the only day they could get permission to close them to the public without disrupting traffic and local businesses.

Unfortunately, Sunday was also the day the Chicago Bears were playing, and the stadium, Soldier Field, is on the city’s south side. “People walk to the stadium down Michigan Avenue… for the love of the Bears,” Besser says ruefully.

This meant that all the shooting for the film’s most dramatic scenes had to be squeezed into the amount of time it takes to play an American football game. “Once the game started around one o’clock on that Sunday afternoon to the time the fans were leaving, we had about two-and-a-half to three hours.”

The trouble didn’t end there. It turned out the production had inadvertently timed their arrival to coincide with the Chicago Marathon, putting further constraints on an already tight schedule. They then lost a day to rain.

So how do you organise and execute a key shoot, involving hundreds of extras and Hollywood stars who have never worked together before, in a matter of hours?

“Look like you have no fear,” Besser chuckles, “and just plough through it.”

The first challenge was to recruit extras. Sorkin wanted the make-up of the crowd to reflect its real ’68 counterpart: “The actual protest wasn’t a bunch of – what would be described as – hippies and diehards in dyed clothes. There were a lot of professional people involved: professors and lawyers and mums and dads.”

More than any other group, the protests were dominated by the young, but the Chicago company hired by the production struggled to recruit enough college-age extras because so many were, oddly enough, in college. On top of that, being an extra wasn’t necessarily the most enticing prospect.

“It’s one o’clock in the morning in Chicago and it’s freezing and you’re getting paid $15 an hour,” Besser says. “So getting people to come back after their first night of working was not always easy.”

In the end, the filmmakers managed to recruit between 250 and 300 extras a day. Crafty shot design was required to give the appearance of a thousands-strong crowd. But this fitted well into Sorkin’s vision of the scenes, which involved lots of vignette shots of individuals and small groups of protestors clashing with police.

To achieve this, stuntpeople ready to simulate the most violent confrontations mingled among the extras. Those playing the police were armed with fake riot batons. “They’re made out of the same wood they use for baseball bats,” notes Youth International Party leader Abbie Hoffman, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, in the film.

The result was a fast-paced, sometimes frenetic sequence of filming. “It was go, go, go from the beginning,” Bessen says. “We’d be shooting, and then the camera might move a little to the right or left, and then the makeup artist Louise McCarthy and her team would run in with blood, and put that on people, and then the cameras would find them again.”

Blood features heavily and disturbingly as soon as the protestors clash with police. It came, apparently, in many forms. Some extras had balloons or patches under their clothes that burst on impact; others had capsules in their mouths that released when they bit down into them.

The nine days the production spent in Chicago sound tumultuous, to say the least.

“Every day there was some catastrophe, but now that we’re months from the actual shooting days, I can’t even remember half of them. I think that that’s the process of filmmaking,” Besser says.

In 1968, thousands of angry citizens faced heavily armed police in Lincoln Park and chanted: “The world is watching.” On a set filled with cameras, there must have been echoes of the same feeling.

“From the minute we called time,” Besser says, “to the minute we finished each night, everybody was running hard.” Perhaps the production had an inkling that the eyes of history would soon be upon them, with the approach of 2020.