Fidelio, Glyndebourne, review: an over-ambitious production salvaged by the singers

One of the results of the closure of our opera houses during the pandemic has been a backlog of planned productions now clamouring for a place in the programme. The problem is acute in a festival like Glyndebourne, which has little flexibility because its schedule is planned so far in advance. Hence the very peculiar solution of placing this full-scale new production of Fidelio, deferred from 2020, in the autumn touring slot – but then deciding that it will not tour and will be seen only in the home theatre.

Still, it is pretty obvious at first glance why this wildly over-ambitious show directed by Frederic Wake-Walker is not made for practical touring. In Anna Jones’s designs, the prison that encloses the action of Fidelio is a huge circular metal gasholder structure which fills the stage. Its tall wiry walls confine movement but also provide a gauze-like surface onto which live footage of the on-stage action by Adam Young of FRAY studio is projected.

When used with restraint and precision, live filming can illuminate motivation and strengthen impact, but this is self-indulgent, the constant huge jumpy moving images distracting attention from the human characters below. In the isolation of Florestan’s prison cell in act two, it becomes positively absurd when all he has for company is a video camera hidden in his chains, which he has to operate himself with predictably uneven results.

Wake-Walker’s concept of the opera as a metaphor for the search for freedom in oppressive regimes leads him to introduce a whole new character, Estella (Gertrude Thoma) whose dreary spoken narration is fortunately cut short as she is bundled away by soldiers, though she does reappear in the second act to urge Leonore (if I got the right idea) to use her personal liberation to change the world for the better.

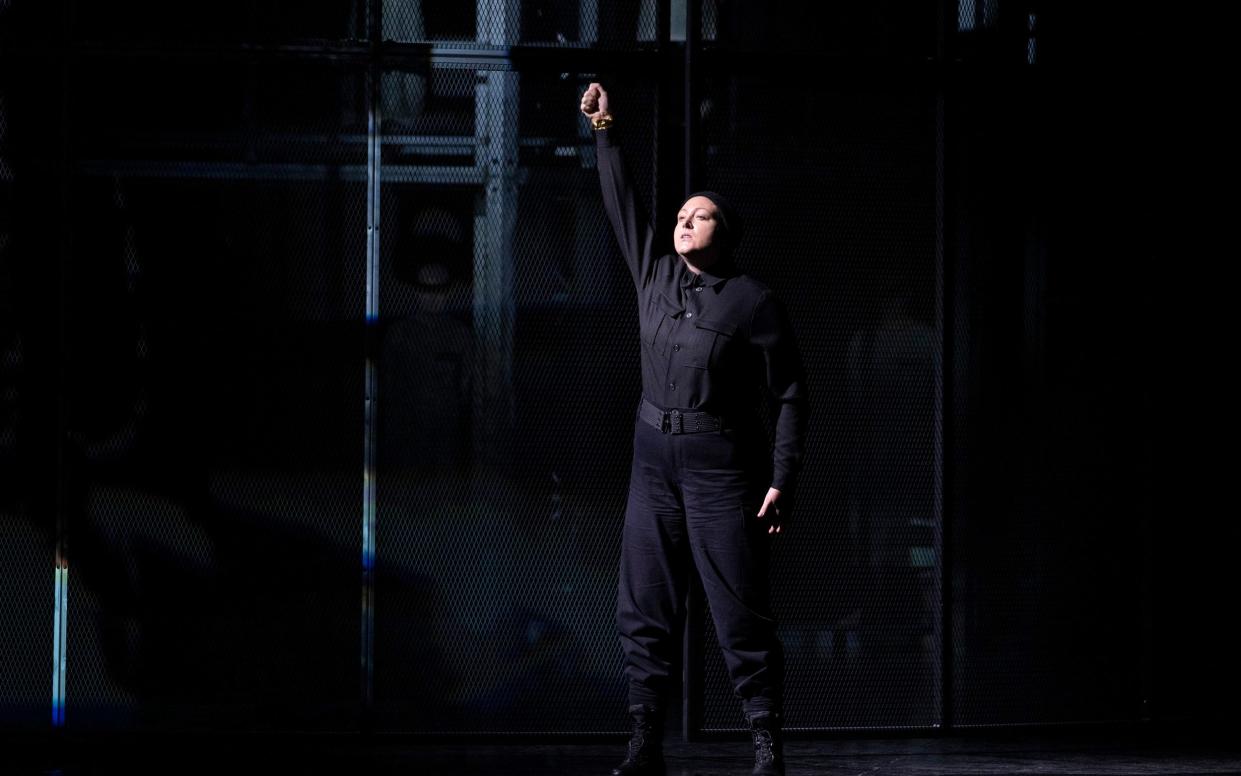

Fortunately within all this distraction there is some fine singing to compel our attention. There is a tremendous house debut from Dorothea Herbert as Leonore, who finds her way to Florestan’s cell disguised as a boy, and reveals herself in music of passionate intensity; she has the necessary wide range and power at the top and bottom of the register.

Adam Smith’s Florestan is equally strong, a little forced, but complementing her admirably in their ecstatic final duet. Callum Thorpe is a wholly authoritative and sympathetic Rocco, firm and focussed, assisting Leonore in her struggle; Dingle Yandell makes a dominating Don Pizarro, though not always secure of pitch.

Jonathan Lemalu arrives at the close as an avuncular Don Fernando to sort Pizarro out, after which the sombre black and white setting gives way to a mad flurry of gold togas for the finale.

In the pit, the Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra has not yet acquired total sophistication, but conductor Ben Glassberg produces some wonderfully atmospheric moments in the introduction to act two, and in the sublime act one quartet, and guides the rest with quiet confidence.

So worry not that you will miss this production on tour: you will probably be better off with reliable revivals of the David Hockney-designed Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, and Donizetti’s Don Pasquale that Glyndebourne will take to its tour venues, with seasonal concerts of Handel’s Messiah to make up the programme.

At Glynebourne until 31 October. C’sall 01273 815 000 to book