Is faded Morecambe poised for a comeback?

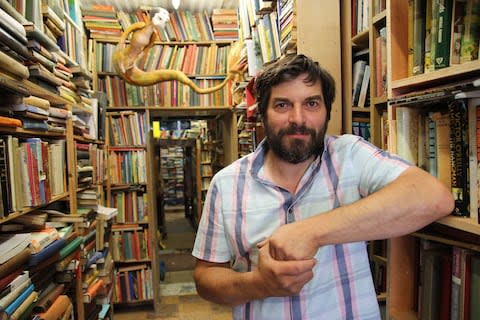

Aronne Vetesse, peers out the door of his Old Pier Bookshop on Morecambe seafront. “We still have the best view in the country,” he asserts.

“It’s better than the Bay of Naples, this – and I’ve been to the Bay of Naples.”

A bold statement, for sure, but looking across the seabird-speckled waters of Morecambe Bay, towards the Lake District’s moody peaks, I don’t feel compelled to disagree. It is indeed a fine view.

During Morecambe’s Fifties and Sixties heyday, that same vista provided the backdrop for tens of thousands of summer holidays, as working-class families downed tools for a week and made for the coast.

Back then the Old Pier Bookshop was a cafe, also run by the Vetesses, and business was booming. “We were able to shut during the winter then,” laughs Aronne, who says those halcyon days are long gone.

The decline of Morecambe mirrors that of other British seaside towns, which were hammered by the rise of cheap foreign holidays, the dismantling of the railways and the demise of working-class culture.

By the Seventies the rot had really set in and Morecambe – a town once famous for its summertime music, theatre and comedy shows – had suddenly become the butt of the joke.

The late comic, Colin Crompton, took great delight in poking fun at the “Costa Geriatrica”, reportedly describing it as a “place where people go to die but forget why they went”.

By the Eighties blue-rinse faithfuls were rubbing along uneasily with DSS claimants, who’d been lured to Morecambe to fill dilapidated guest houses, earning the town another unwanted moniker: the Costa del Dole.

The Eighties marked a new nadir and in hindsight there was something symbolic about the death of Morecambe’s most famous son, John Eric Bartholomew (stage name Eric Morecambe), whose hometown seemed to have followed him to an early grave.

Something unexpected happened in the Nineties: Morecambe was thrown a lifeline by, weirdly, Noel Edmonds, who gained messiah status locally when he and his pink and yellow sidekick, Mr Blobby, opened a theme park in the town.

Despite some scepticism, Crinkley Bottom didn’t appear to be full of hot air with strong ticket sales suggesting that it could save the town. But Edmunds and the council fell out and the attraction closed after just four months (a court case between the two parties resulted in the council paying the TV star £950,000 in damages).

“That’s all in the past now,” beams Vetesse, whose labyrinthine bookshop is a place where many happy hours are whiled away. “Morecambe has turned a corner.”

Back to the glory days?

One of Morecambe’s fatal flaws was that it never got a truly grand hotel, but the rebooted Midland has finally addressed that.

Saved from the wrecking ball in the dark old days, the Art Deco property reopened to much fanfare in 2008 and spearheaded the redevelopment of Morecambe promenade.

The fancy cars outside suggest the property is bringing money to Morecambe. Most of the gas-guzzlers would have come in on the new bypass, which provided Morecambe with a welcome link to the M6.

Building a road is easy, compelling people to drive down it is the hard part. That a statue of Eric Morecambe is currently the town’s top rated attraction on TripAdvisor illustrates the scale of the challenge.

Then there’s the poverty, which seems almost Dickensian in the town’s West End. Even parts of the seafront have a gloomy resignation with once-glorious Art Deco department stores now housing bargain shops and bed retailers.

“We can’t get away from the fact that this is a low-economy place,” explains Alex Zawadski, creative producer at Deco Publique, a Morecambe-based project that uses art and culture as a tool for civic regeneration.

After working as a guide in Borneo and a jeweller in Florence, Zawadski returned to her native Morecambe to help pioneer its regeneration. She now helps organise the town’s annual Vintage By The Sea festival and has been instrumental in putting art into public spaces.

“It’s about placemaking, making people feel like they have ownership of places,” explains the garrulous redhead, walking me around some murals, which festoon what’s left of the old lido.

It is on this brownfield site that the town’s hopes are pinned. For this is where the Eden Project has been conducting a feasibility study in lieu of opening a northern outpost of the popular Cornish attraction.

The original Eden has contributed a reported £2 billion to the local economy and welcomed more than 20 million visitors since it opened in 2001, so the stakes are high.

Zawadski takes me to Morecambe’s inglorious Arndale shopping centre, which seemed like a good idea in the Seventies. The building replaced the Victorian-era Royalty Cinema, which was converted into a bingo hall following dwindling ticket sales, before finally being pulled down.

Now it’s the shopping centre whose fortunes are fading as e-commerce threatens traditional stores. That the White Elephant Gallery has moved into one of its vacant units shows, perhaps, how things have moved full circle: art, replaced by retail, replaced by art.

“A lot of galleries in Shoreditch and Manchester’s Northern Quarter would love our footfall,” explains curator, Paul Kondras, whose gallery “shows interesting work in a non-patronising way.”

Kondras and co-curator, Neil Wilson, have lived in the area for years and sense the tide is changing.

“Things are coalescing after years of decline,” says Wilson. “People are cottoning on to the fact that you have got access to big cities, the Lakes and Dales here.”

With one-bed flats going for around £32,000 there are certainly opportunities for remote workers, reckons Peter Wade, a local guide, who I meet outside the old seafront railway station. It’s now a pub.

“For people who can make a living online, Morecambe is a great destination,” he says, as we do “the Eric pose” next to the seafront statue of the comic.

Wade has ridden the Morecambe roller coaster and is a trustee at the Victorian-era Winter Gardens, a Grade-II listed redbrick theatre, which has clung on but seen better days.

“It’s a case of plodding on and hoping an investor comes along with the money,” he sighs, as we walk around the theatre’s dusty backstage. A metaphor for the town, I muse. He nods.

Wade seems unwilling to get his hopes up about the future of Morecambe – like everyone else, he’s been bitten before – but deep down I detect cautious optimism.

Later that night I walk along the prom from the Smuggler’s Den, one of Wade’s pub recommendations (a fine one, too). Music blares from a seaside tavern and I can’t help but chuckle at the song: it’s Don’t Stop Believing by Journey. For Morecambe right now I couldn’t think a more fitting soundtrack.