The Faces of Domestic Violence

In June 1975, Mableine Nelson Barlow was shot dead by her ex-husband, two days after their divorce. Her ex was in a drunken rage, and she ran down the street in Compton, California, with their 16-year-old son. Bullets from a 25-caliber handgun riddled her body, and the 36-year-old mother of seven died in her uninjured son's arms.

Mableine's ex husband was never charged for the murder. Years later, he had a religious awakening and sobered up, determined to rebuild a relationship with his estranged children. Eventually, he was allowed back into the family. No one ever spoke of Mableine's death.

That man was photographer and artist Chantal Barlow's grandfather. Barlow grew up only knowing the grandfather who captured every family memory with his trusty camera and didn't find out about his actions until she was a teenager. "By this time, I had a strong, loving relationship with him, and was conflicted for many years to come," she said.

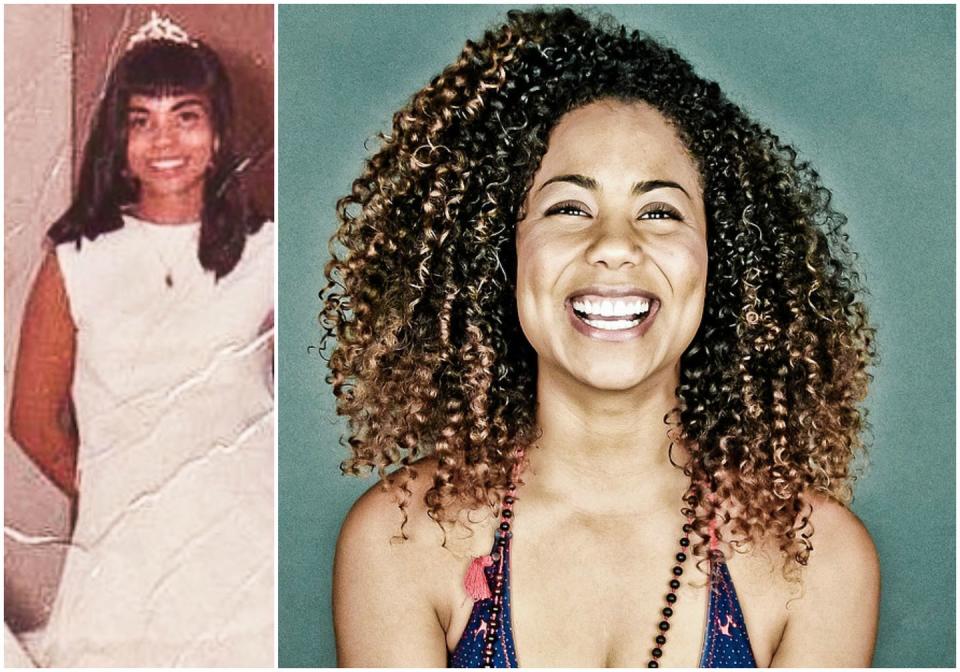

When her grandfather died, an old man surrounded by family, he bequeathed Barlow his prized camera. His life was well-documented and even celebrated, while Mableine's virtually disappeared into the silence of memory. Barlow has only seen three photographs of her grandmother. So, she decided to use her grandfather's camera to photograph women who have experienced domestic violence. She plans to shoot 36 women in total — one for every year her grandmother's life — and each participant wears blue, in honor of Mableine's favorite color.

Dr. Susan Hammoudeh

When I was 23, I met this boy at a bar. It unraveled pretty quickly. Some of the red flags that I saw that I chose to ignore were the yelling and the screaming — like road rage, towards a neighbor, towards a roommate. He had a very traumatic childhood, so I was very sympathetic. Then it started to be directed towards me. And I was in such shock because no one has ever spoken to me in such a way, the most derogatory, racist, sexist names. I look back and I'm like, why didn't I just leave?

The abuse turned sexual, primarily when he was intoxicated. That was always the excuse: "Well, I don't remember any of it. I don't even know if this happened." Some nights were so horrific, and when I would tell him what happened the next day, he would feel bad and then I would feel bad. Then he would accuse me of lying. He had a really hard time accepting responsibility.

There was some physical abuse as well: roughhousing, pushing me around, pulling my hair. Again, it was "I was drunk, I don't remember." One night he came over uninvited to my apartment. He was completely intoxicated. But he comes over and rips my clothes off, pins me down to my bed, spits in my face, raises his fist at me, and I'm screaming. He ended up passing out, as he was raping me... I took a shower, and I went to work.

Then there was a day where he came over uninvited, totally sober, and raped me. Afterwards he said, "Do you see what you made me do? I didn't wanna have to do that." I was completely beside myself. We get in the car to get cigarettes from the gas station and he's like, "What would you call that?" And I'm like, "What?" He's like, "What just happened. You were saying no." And I looked him in the eye and I said, "Rape." He got out of the car, got his cigarettes and that was it. How do I process my boyfriend raping me and then blaming ME?

I kicked him out because my mom was coming to visit me. She didn't know the details, but she knew that something wasn't right. One day, my mom and I were on the road, running an errand and there he was. Driving right next to me. And we pull over into a parking lot and he starts yelling at me and yelling at her, and telling her how all of this is my fault. He eventually left. She's like, "Listen. There's nothing that he can do or say to us that would ever make us leave you." I was ashamed and embarrassed. But hearing those words gave me the motivation to just say, "I'm out of here, I don't care how he's going to retaliate, I'll be able to fight and deal with it because I want my present and I want my future." And that's how I did it. It was hard. It was a good year or year and a half with the emails and the phone calls. But eventually he stopped. He stopped calling, he stopped emailing me, stopped texting me, stopped trying to find me.

There's hope. At your darkest hour, when you have given up already because you're TIRED … and you maybe have tried and you haven't been able to get out, there are options, even if they're difficult to see. You need to be able to reach out to somebody … just one person. You can have your present and you can have your future.

Peggy Reyna

I'm a survivor of domestic violence. I became profoundly deaf from that event. It was many years ago and, of course, it was the ending to many years of abuse. I married at the age of 16 and the person that I married was an abuser. We lived together for 12 and a half years. Finally, I divorced him. Later, I married a second person and that person was a terrible, much worse abuser. On the final day of violence, he threw me against the wall. He jumped on my head and snapped my neck sideways. Left me with a jaw broken in two places, my nose broken, all my teeth kicked out, blood running out of my ears, and profoundly deaf. Through the next few years, I had several surgeries that repaired most of that.

The important thing for me to talk about is the intergenerational cycle of violence and what happened to my family. In particular, my daughter Dream. Dream was already a teenager when I got free from domestic violence. She was already dating the person that she would eventually marry, her abuser. Through the years, I talked to her a lot about domestic violence, about leaving him, about getting restraining orders. She always, always went back, same as her momma always went back so many times. And in 1995, he put a gun to her head and he killed her.

I think it's so important to know that domestic violence is intergenerational. It comes not only from learned behavior, but from learned acceptance to how other people treat you. If you grow up in a home where you see your mother accept that someone beats her up, punches her in the face, kicks her in the stomach, throws her across the room — then she gets up and cleans up the blood and cooks dinner and makes love to him — what you learn is that that's an acceptable way to do relationships … but it's not.

I went on and got a degree in special education with a focus on deafness. Eventually, I moved to Los Angeles and also eventually, became the Project Director of the Deaf, Disabled and Elder Services Program at Peace Over Violence, a domestic violence prevention and intervention agency in Los Angeles. I've been here 25 years.

As I grew more and more emotionally free, I began to feel physically more well, too. And I began to see my life change and then slowly and unbelievably, I saw my children and my grandchildren's lives begin to change. It was too late for my daughter, Dream. But I know that she would be so thrilled to look down and see my grandson and his wife and his two children live in a home absolutely free from violence. No one ever hits them, no one screams at them, no one does that and they get to see it; they live in a different kind of life. Through that, I learned that healing from domestic violence is also intergenerational. That's really the message that I want to give to the world. That you can change. And when you change, those that you love can change because you become the role model.

Tamieka Smith

He was a very, very jealous person. One day, after I got the kids from daycare, he called, telling me, "I need to know everything you talked about during your whole shift." After I got the kids in the house, [he was] asking me about talking to this guy and our conversation. I was telling him nothing was going on. And he said, "I don't believe you." Grabbed me by my arm while the kids were watching (they were only 1 and 2 at the time), and dragged me to our bedroom. He then grabbed his hand around my neck and just started slamming my head against the mirror. Telling me, "All you wanna do is look in the mirror! You wanna look good for somebody else!" He got a pillow off the bed and tried to smother my face. Then he took the pillow off of me, put his hands around my neck, and I was just pleading with him. When he did let go, I asked him, "Do you want to have the boys see you doing this?" That's when he just snapped out of it. I knew then it was time for me to go, or I wouldn't survive. I wanted to see my kids graduate from high school. I didn't want them around that anymore; before they got old enough to realize what was really going on.

After that incident, I decided that I needed to have some kind of game plan to get out of that situation and not come back. It scared me that he knew where I would go, my mom's house. I knew that I had to pretend to basically act like I was gonna be late for work so we could leave. And that's what I did. I pretended to oversleep. I knew he had to be at work before me. Then I packed everything I could in this little Mazda Protégé, with the kids and trying to get all our possessions in this car in a matter of 15, 20 minutes. I looked at them and told them, "When I held you, I told you I was gonna protect you. That's what I'm gonna do."

So we did leave. Once he realized I wasn't at work, he came to my mother's house.When I saw him and another guy... I just started shaking and called 911. And nobody answered the door. By the time the police came, he was gone with the car and the kids' car seats in it. Which I thought was really idiotic and him still trying to control the situation. From that point on, I had to fight to get a domestic order of protection against him. Even though I paid for the car, I just told him, "You can have it. I just want my life. I just wanna live. We just wanna live. We deserve that."

Being a person of strong faith even though I went through a hell of a lot of adversity and lived in a shelter for 10 months, I always knew that things would get better. And, eventually, it did. No one is worth going through hell with. Nobody. Especially when it comes to somebody trying to threaten you, or your family, or even your kids. It's not worth it.

Good Shepherd Shelter, a domestic violence women and children's shelter in Los Angeles, has partnered with Barlow to document the impact of the shelter's comprehensive domestic violence services on their "after care moms" — women who have been out of the shelter for several years. Barlow crafted new, shelter-focused questions for these interviews, and she shares an exclusive first look with Good Housekeeping.

Candida Magallanes

Being in the shelter helped me transition from victim to survivor. From being a woman that was afraid, wanting to run ... to hide, to becoming a woman that could do her own things with her children. I would tell other women at the shelter to see that children need to know that there's hope. That violence is not normal. Teaching them a new face … that things can be done without violence.

Cristina Jara

My time in the shelter had a very large impact on me because I didn't know I had a lot of capacity to do. I came from a family where there was not a lot of communication. I didn't know I was experiencing domestic violence. For me, it was normal. And when I noticed that something was wrong, and when I came here I knew that you didn't have to be hit or to see violence. Here [at the shelter], they taught me that women have rights. We deserve to be loved and respected. And I love that and I wanted to be like that. I wanted to love myself and respect myself. I proposed that. It was kind of hard [to break] the family tradition but I feel good today and I feel good that I stayed here.

I would suggest women currently at the shelter to just enjoy this place. It brings a lot of peace. And sometimes we pass through here but we don't appreciate the help they give us and we go out to [abuse all over again]. And we need to learn how to appreciate the help that they bring here. Everybody that comes and gives the talks, the outings that we go to, the presents that they bring. And once you leave here, it's very hard because we don't have their protection. We have to learn how to appreciate everything that they give you here that stays with you once you leave. That helps you become more secure.

We all deserve to be respected, loved and admired. If that's not happening in our house that means that something's wrong. Don't be afraid to talk with family if there are problems in the relationship and don't be afraid to ask for help, or embarrassed. Because that's what makes us continue in a relationship that's hurting us, and we deserve to be happy.

Reyna Valenzuela

For me, being in a shelter transmitted peace for me, tranquility. I learned that I can do it. I can be a survivor. I don't need someone to be bothering me all the time. It's not something I have to accept. If I have the chance to talk to any of the other moms right now, I'd say, "Don't look back. You're safe. If you want to get out because you want to get out of here, you're free to do it, but don't look back." That's the first thing that I'd tell them. Don't look back; always forward. And to remember, if they're not fine, their kids are not fine. Kids look after the mommies. Kids do like mommies do all the time.

This story is part of an ongoing series about domestic violence and abuse. If you or someone you know is at risk, reach the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233. If you are in danger, call 911. More information and resources are available at the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence or the National Online Resource Center for Violence Against Women.

You Might Also Like