Elizabeth I versus Mary Queen of Scots: the royal letter that rewrites history

Sometimes you just hit lucky. In 2010, six years after I finished my biography of Mary, Queen of Scots, Sotheby’s invited me to examine a cache of Elizabeth I documents that they were offering for sale. Intrigued, I paid a visit to New Bond Street, where, breathtakingly, 43 documents in pristine condition – more than half signed by Elizabeth or her leading courtiers – were laid before me.

All shed fresh light on the penultimate phase of Mary’s 19-year imprisonment in England, many illustrating a mounting obsession over the possibility of her escape, as the threat of foreign invasion grew. One thrilling letter changes our view of history.

Missing since 1762, the documents had clearly been purloined around that time from the papers of Sir Ralph Sadler, Mary’s gaoler in 1584-5, to whom most of them are addressed. As an ambassador to Scotland in the early 1540s, he’d held the baby Mary in his arms.

The documents had been hastily ripped out of a bound volume. They passed through the trade, until purchased by the late Lord Hesketh, whose estate sent them to Sotheby’s. Sold for £349,250, they promptly disappeared again.

Now, miraculously, all 43 items are on long loan to the British Library. Several will star in a landmark exhibition, Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens, which opens next week. It’s the first major show to consider Elizabeth and Mary together, putting both women centre stage and giving them equal billing, each on her own terms. It tells their stories from their autographed letters, state papers, drafts of speeches, portraits, drawings, jewels, textiles, cipher codes, maps, and woodcut engravings.

Highlights include Elizabeth’s handwritten translation of her stepmother Katherine Parr’s Prayers and Meditations – a gift for her father Henry VIII – together with her personal crib for a fiery speech dissolving parliament in 1567, and a treasured locket ring, which opens to display miniature portraits of herself and her mother, Anne Boleyn.

From Mary’s side, we’ll see her handwritten letters to Elizabeth, several in French, others in Scots and English; fabulous portraits by Fran?ois Clouet and Nicholas Hilliard, and the gold necklace and heart-shaped locket known as the Penicuik Jewels. An eyewitness drawing of Mary’s execution and hauntingly lifelike casts of the tomb effigies of both queens from Henry VII’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey complete the spectacle.

Even so, for me the prize is the document the British Library’s curators now call the John Guy letter, the one that rewrites history. It proves conclusively that, in defiance of her ministers, Elizabeth sought a last-minute reconciliation with her rival, possibly even a meeting – as has been imagined in Schiller’s play Mary Stuart, Donizetti’s opera Mary Stuarda and Hollywood films such as Josie Rourke’s Mary Queen of Scots.

When the letter was written in October 1584, Mary had been imprisoned for 16 years. Overthrown by her Scottish rebels, who ruled in the name of her young son James VI, she had fled across the Solway Firth to England in 1568, presenting the Protestant Elizabeth with a stark choice: should she protect her Catholic cousin, maybe even restore her to her throne, or treat her as a threat?

Elizabeth’s chief minister, Sir William Cecil, and her spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, had no doubts. Just months before, Walsingham had frustrated a dangerous plot to kill Elizabeth that had been backed by Spain, the pope, and Mary’s Catholic relatives. Mary had once claimed to be the lawful queen of England. Elizabeth’s “security” and the “safety of the state” depended on keeping her locked up. So far, Cecil and Walsingham’s arguments had prevailed. A chilling superscript to a set of Sadler’s instructions, also from the Sotheby’s cache and included in the exhibition reads: “Use but old trust and new diligence, your affectionate, loving sovereign, Elizabeth R.”

And yet, when Elizabeth yielded to her instincts, everything changed. It wasn’t plain sailing. Two years before, Mary had asked that the “jealousy and mistrust” she claimed her cousin had conceived of her should be removed. Elizabeth icily chided her for this, but swiftly softened, recounting that Mary had now written to her “in a most kind and friendly sort”.

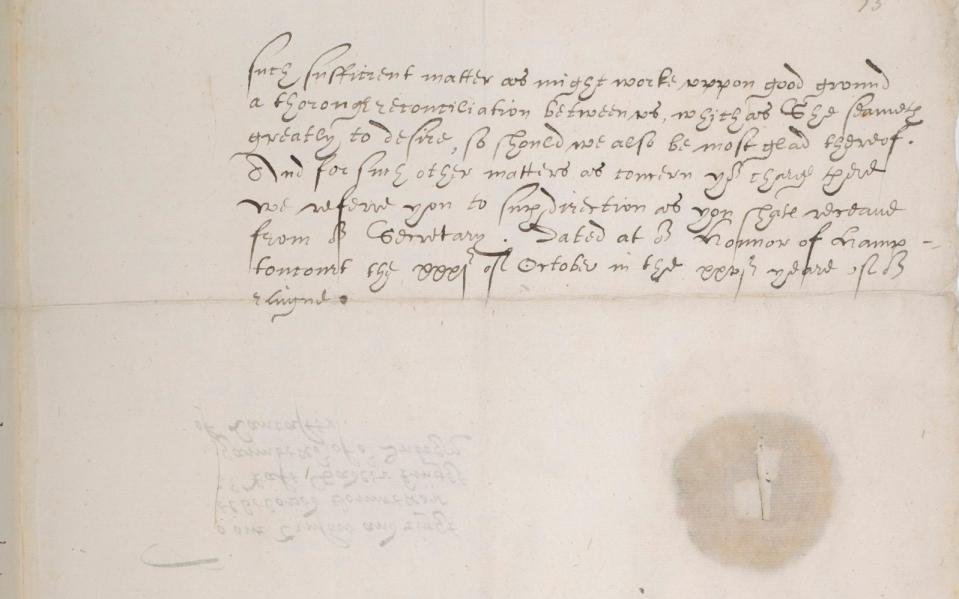

The “John Guy letter” is addressed to Sadler, but he was to show or read it to Mary. To avoid a fight to the death, Elizabeth tendered an olive branch. She was “content to assent” that Mary’s confidential secretary, Claude Nau, should ride south “to acquaint us with such matter as she shall think meet by him to impart to us”. He was to bring with him such proposals “as might work upon good ground a thorough reconciliation between us, which as she seemeth greatly to desire, so should we also be most glad thereof”.

Seeing this letter headlined in the upcoming exhibition is, for me, a personal vindication. I’d always suspected that a letter of this sort could turn up. Deep down, what Elizabeth really wanted was to settle with her cousin, as Mary did, too. Elizabeth didn’t feel this way because both rulers were women (although that played its part), but because Mary was a sovereign, and not a subject. To put a fellow sovereign on trial and execute her was akin to sacrilege.

Six weeks after Elizabeth wrote her letter, Nau presented her with Mary’s proposals. They’re tucked away in the National Archives in Kew. I knew about them before, but not why Nau submitted them at this moment. I’d assumed him to be acting off his own bat, thrashing about in the dark. Finding Elizabeth’s letter inviting them is the missing piece of the jigsaw.

Closer investigation shows that Elizabeth took the proposals so seriously, she disappeared for a month to reflect on them in conditions of absolute secrecy, to the consternation of her ministers.

Mary was offering close to total surrender. In exchange for her freedom and the right to return to Scotland to rule jointly with her son, she would recognise Elizabeth as the lawful queen of England and never again claim her throne, would not support her cousin’s rebels, would not conspire against her, would uphold the Protestant Reformation in Scotland (although without changing her personal faith), and so on. Elizabeth, moreover, was to have a veto on James VI’s marriage, and he was to join with her in approving a final settlement.

All came to naught. There would be no reconciliation, no last-minute meeting of the two queens. Scriptwriters down the centuries would be forced into fiction, but failure cannot be laid at either queen’s door. The negotiations collapsed only because James, now 18, had no intention of sharing his throne with a mother he barely knew, or being married off by Elizabeth. Instead, he informed Mary that he would always honour her with the title of “queen mother”, but that was all. There could be no question of joint sovereignty or her return to Scotland. Instead, James made his own defensive treaty with Elizabeth, ratified a year later.

For Mary, this was matricide, the cruellest of betrayals. “I pray you to note”, she fulminated in a letter to James, “I am your true and only queen. Do not insult me further with this title of queen mother... there is neither king nor queen in Scotland except me.” Her unbridled, secret correspondence with her Catholic supporters across Europe over the ensuing months – which Walsingham intercepted – was her direct reaction to her son’s rejection.

When, in her desperation, she connived in the infamous Babington Plot of 1586 to abduct and kill Elizabeth, she left her cousin no choice but to put her on trial and reluctantly sign her death warrant. Now it was Elizabeth’s turn to sink into deep despair as she sought in vain to shift the responsibility for ordering Mary’s death onto others. It was her Armada of the soul.

John Guy is a Fellow in History of Clare College, Cambridge. Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens is at the British Library, from Oct 8 until Feb 20. Tickets: bl.uk