Dutiful, never thrilling show presents Sophie Taeuber-Arp as a creative jack-of-all-trades

Tate Modern’s new exhibition is the first British retrospective for Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the Swiss-born – well, I was going to say “artist”, but the gallery opts for “crafts professional”. Fair enough, given that the show is chock-full of rugs and tapestries and folksy cushion covers and pillowcases, as well as beaded chokers, pouches, and scrunchy-like bracelets, all of which, it suggests, are as worthy of our attention as her abstract paintings. But, as phrases go, “crafts professional” doesn’t generate much excitement (on her business card, she preferred “architect”); and it sets the tone for a show that feels dutiful (insisting, as it does, that applied arts should be front and centre) but never scintillating. Lots of technical preparatory drawings, as well as axonometric projections, presentation albums, and the like – but little to thrill the soul.

Born in Davos in 1889, Taeuber, as she was before she extended her surname after marrying the Dadaist Hans (Jean) Arp in 1922, is less well known here than on the continent. So, the opening gallery provides an introduction, with a short biographical film and a wall of black-and-white photographs that track her life before her accidental death, aged 53, from carbon-monoxide poisoning. Here she is, at a party in Switzerland in 1925, wearing a corrugated-cardboard costume. A couple of years later, she’s beside the sea in Brittany, sporting beachwear designed by Sonia Delaunay-Terk. Evidently, then, she was more than a bit-part player in modernism’s compelling drama, a stylish dresser (and dancer) who was friends with “tout le monde”.

She trained in Munich and Hamburg before falling in with the Dadaists in Zurich, and the cavernous second room swallows up lots of tiny examples of her output from this period. I’m not convinced that her modest crayoned grids, known as “vertical-horizontal compositions”, ever set the world on fire: the odd gilded frame cannot compensate for the pictorial lustre they lack. Her turned-wood Dada objects, though, are pleasing, like hats for Bassett’s liquorice-allsorts mascot; a tongue-in-cheek portrait of Arp resembles an Easter egg decorated as an irritable owl. A troupe of marionettes created for a theatre in Zurich in 1918, also made on a lathe, and elegantly finished with feathers and scimitar-sharp metal hardware, are memorable too. One militant robotic critter, representing a phalanx of guards, could be a geriatric Dalek waving a set of walking sticks.

After the war, Taeuber-Arp took up architecture and interior design, which is why the show includes so many technical drawings, as well as examples of her underwhelming furniture. There are also a few boring black-and-white photographs that she took on her travels. So, she visited the Colosseum: who cares?

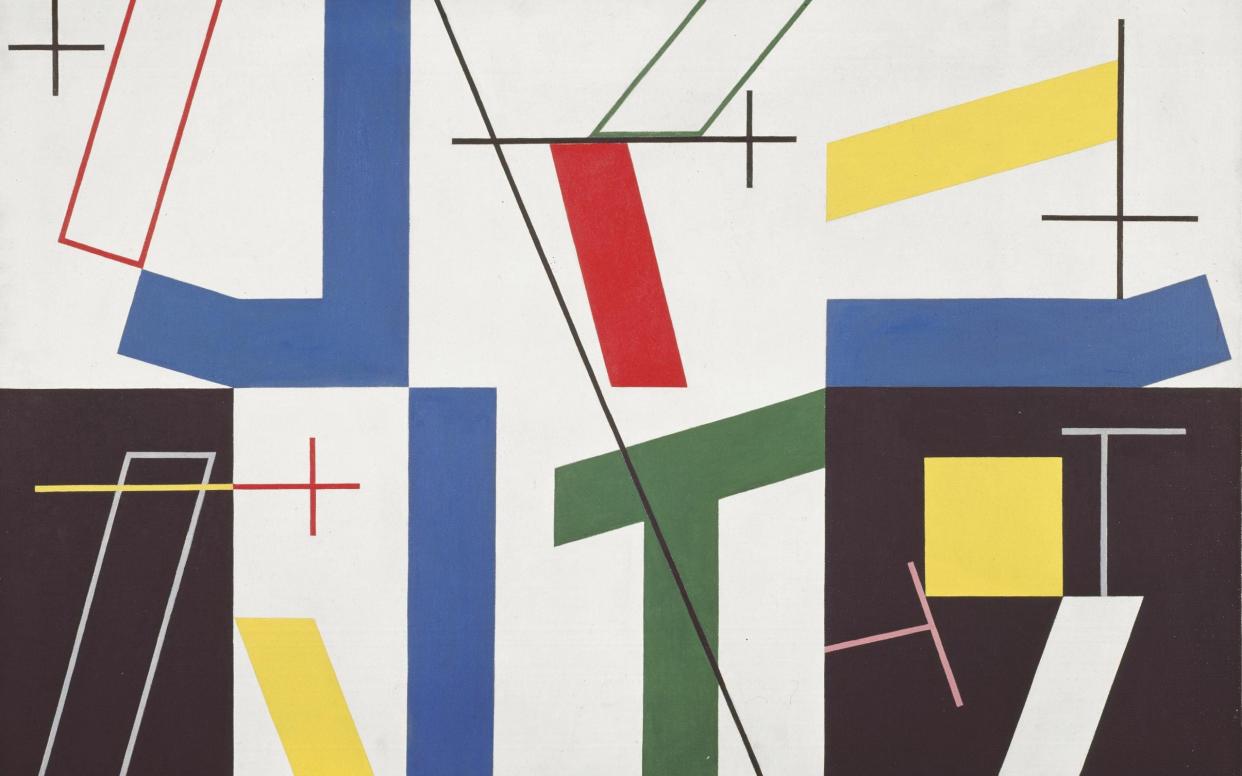

After settling permanently in France, though, in 1929, she produced lots of satisfying abstract paintings resembling dominoes or wiring diagrams, limiting herself to bold, flat colours and simple motifs (circles, squares, thin crosses, parallelograms). Conjuring a captivating sense of movement, they’re like intricate mechanisms whirring with interrelated parts. Orderly circles appear to clack together like beads on an abacus. Lines and polygons seemingly switch back and forth with the oscillating precision of a desktop toy. Click!

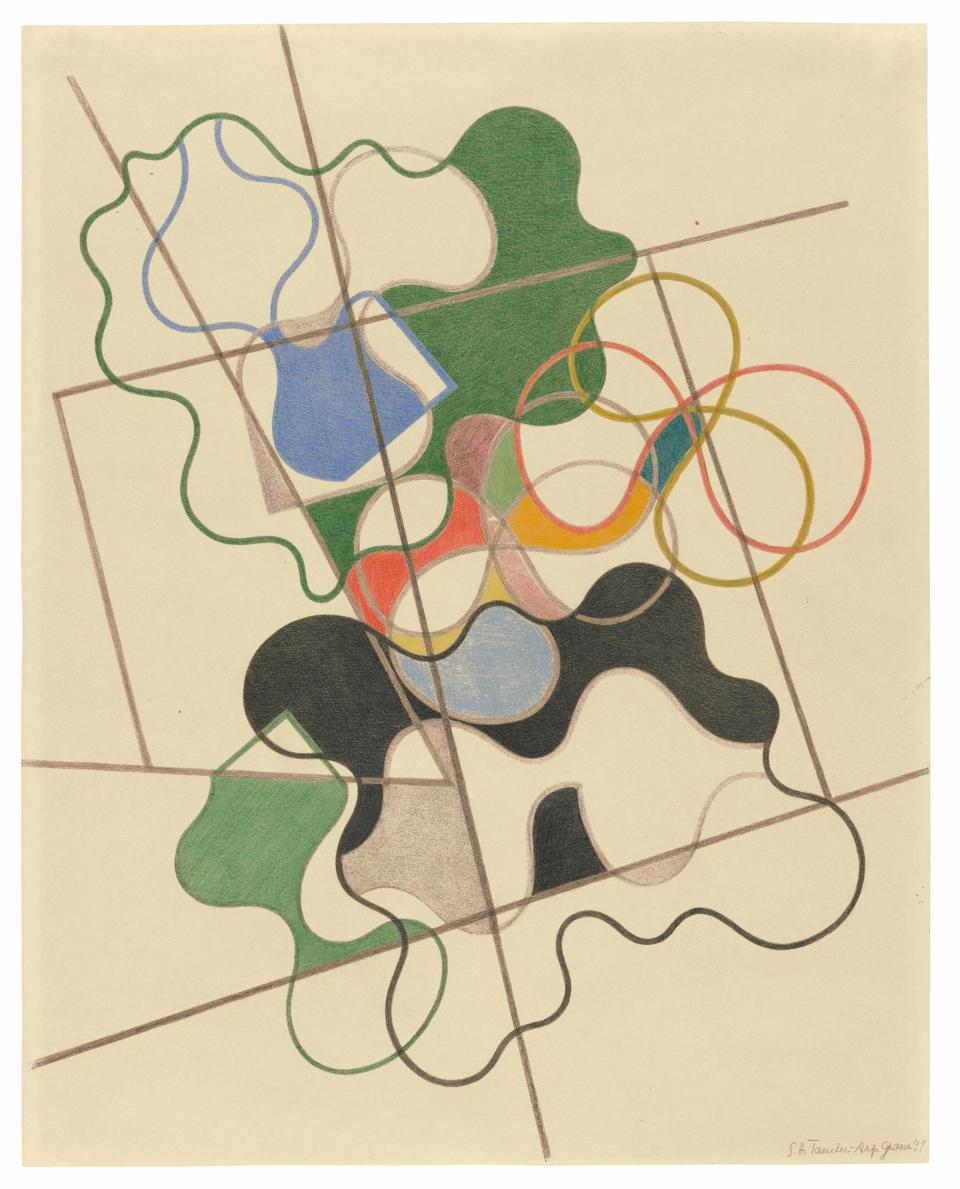

By the Second World War, Taeuber-Arp’s approach was much more organic and fluid: I kept thinking of the later American artist Brice Marden. The conflict, though, took its toll: her inky final works, albeit as sleek as a Leica chassis, are full of fractured forms and conical, searchlight-like shapes. Mostly, though, Taeuber-Arp comes across as an avant-garde jack-of-all-trades, an enviably creative jobbing professional who carved out a successful career in many spheres. How much you’ll want to engage with that career is up to you.

From July 15 until Oct 17; information: tate.org.uk