This District in Birmingham, Alabama, Showcases the Work of Three Significant Black Architects

At first glance, Birmingham’s Civil Rights District may appear like any other historic district in the country. You’ll find tourists stopping to read markers detailing important events of the movement, locals strolling through Kelly Ingram Park during their lunch breaks, and students lining up to enter museums for school field trips. However, what many people don’t realize is that scattered throughout those city blocks are hidden architectural treasures that tell the story of Black excellence.

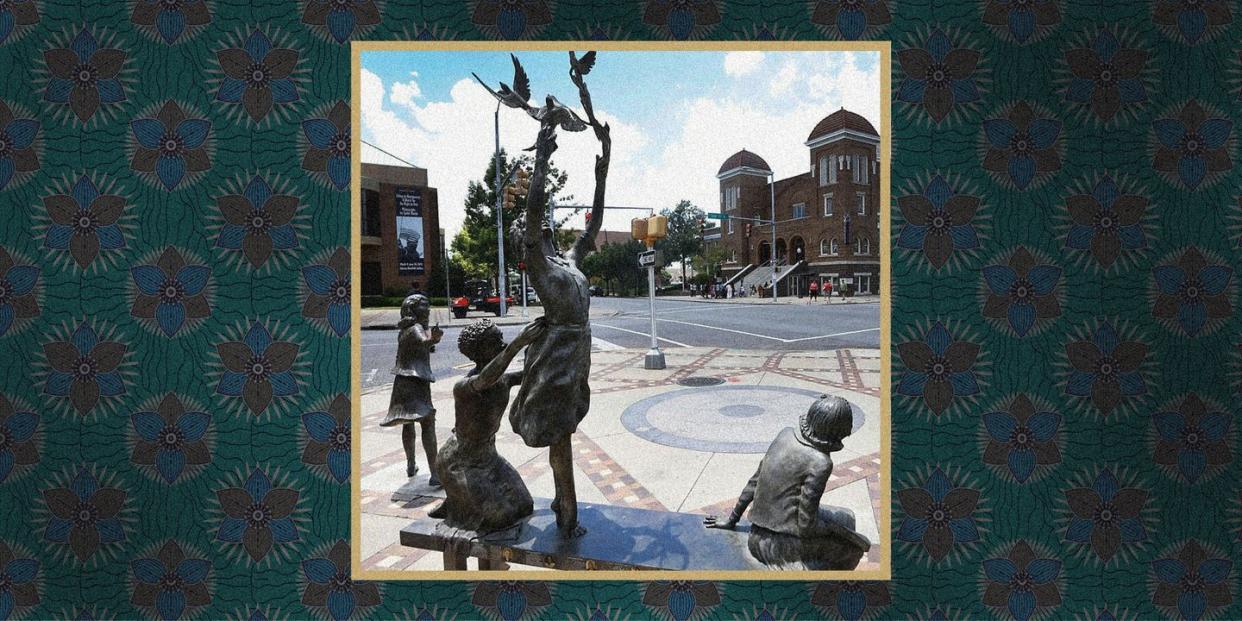

The district is one of the few places in the nation that showcases the work of three Black architects spanning different generations: the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and Parsonage by architect Wallace Rayfield, the Masonic Temple Building by architect Robert Robinson Taylor, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute by architect J. Max Bond Jr.

“I consider this three to four block radius to be one of the rarest cultural landscapes and historical environments in the United States that presents to our nation the contribution of two generations of Black architects,” says Brent Leggs, senior vice president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and executive director of its African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

Leggs first started working with local leaders in 2015 as part of an advocacy campaign to establish the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument. During the 1950s and 1960s, several significant moments in the fight for racial equality took place in the streets and buildings within the now-recognized Civil Rights District. Officially designated by President Barack Obama in 2017, Birmingham’s national monument encompasses roughly four city blocks of the district and includes sites of Black history like the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and Masonic Temple Building.

Denise Gilmore, who previously worked with Leggs at the National Trust, serves as Birmingham’s senior director of the division of social justice and racial equity; in her current role, she oversees the preservation and advancement of the monument. For her, the buildings show the important role Birmingham played in the modern Civil Rights Movement and shines a light on local heroes.

“These sites recall the struggles,” says Gilmore. “The buildings provide the narrative and the stories for what happened in the fifties and sixties in the struggle for civil and human rights.”

One of the city’s most recognized landmarks is the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church by Wallace Rayfield. Born in Macon, Georgia around 1873, Rayfield was only the second formally trained Black architect practicing in the United States at that time. He earned degrees from Howard University, Pratt Polytechnic Institute, and Columbia University before being recruited by Booker T. Washington to teach at Alabama's Tuskegee Institute. In 1908, he opened his own architecture practice in Birmingham, where he focused on creating safe spaces in churches for Black people to gather. Gilmore notes that Rayfield "was prolific in terms of his architecture and his designs that were built in Birmingham."

Completed in 1911, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, the most famous of Rayfield's Birmingham projects, blends together elements of Romanesque and Byzantine design and showcases Rayfield’s meticulous attention to detail. Due to segregation in the city, the church quickly became a social center for Black residents of Birmingham and later a headquarters for organizing during the Civil Rights Movement.

Most people know of the church due to the bomb blast that killed four Black girls in 1963. Leggs notes the events that took place at the church were catalytic in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Today, it serves as a leading example of how local community members not trained in preservation can take stewardship of important architecture to help tell its full story.

“It's beautiful to see how the church, over the past decades, has grown its stewardship capacity to be an exceptional caretaker of the historic church building, and also, the recent reimagining of the parsonage to tell an overlooked story about the architectural significance of the church, as well as to present to the public the lesser known contribution of an amazing American architect,” says Leggs.

Just a couple of streets over stands architectural work from the first accredited Black architect in the U.S.: Robert Robinson Taylor. He was the first Black graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he majored in architecture. Similar to Rayfield, Taylor was recruited by Washington to design new buildings on Tuskegee’s campus and to develop its architectural program.

Between 1922 and 1924, Taylor worked with Louis Persley, the first Black architect registered in Georgia, and the Windam Brothers, a Black-owned construction company, to design the Masonic Temple Building in Birmingham’s 4th Avenue Historic District. The 8-story building, decorated with grand Greek columns and marble decorative details, was one of the few places where Black entrepreneurs could open a business in Birmingham during the city’s long period of segregation. Black residents would flock to the grand skyscraper to see the doctor, get a haircut, and even attend concerts in the building’s first-floor auditorium. Musical greats such as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie played at the temple numerous times. It also later became a place where Civil Rights Movement leaders and groups such as the NAACP would meet to plan and organize.

Irvin Henderson, the managing partner for Historic District Developers, which is renovating the Masonic Temple, says, "The building is an example of collective economics from a period of time when folks were dealing with everything from Jim Crow to outright lynching. Amidst turbulent times, African Americans were making this economic statement and providing for themselves."

As the city finally became desegregated, the building fell into a deteriorated state. Milton S. F. Curry, dean of the USC School of Architecture at the University of Southern California, notes that early Black architects like Taylor and Wallace had major roles in shaping the nation, but so often their work is overlooked and the buildings are neglected.

"The significance of these architects who designed these cultural artifacts, these buildings that anchor African-American communities, were not necessarily lauded as major architects nationally or even regionally because either the scope of their work or the aesthetics of their work didn't adhere to the kind of conventional references of defining excellence in the field," explains Curry.

The temple had been vacant for nearly a decade before the Historic District Developers, a joint venture between Direct Invest Development LLC and Henderson & Company, announced their plans to restore the Masonic Temple Building with the intention of making it a center of commerce once again in 2019. Henderson notes the Masons will remain the main tenants but the restored building will also house a restaurant and professional offices and the auditorium will be used as a performance venue once more.

While not officially a part of the city's national monument, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute was intentionally built to complement the historic structures surrounding it and help tell the city’s history. J. Max Bond Jr. was selected as the lead architect on the project where he even helped to establish the Institute’s mission and program. Bond graduated from Harvard University with a Master's in Architecture in 1958 and co-founded the architectural firm Bond Ryder Associates with Donald P. Ryder in 1969. His most enduring legacy may be his role in designing several of the country's top civil rights and Black culture research institutes.

“Here was someone who, in a way, was making tangible the rewards from the civil rights struggle, which he saw with his own eyes as a young man,” says Curry. “He was translating those rewards into history and architecture.”

Bond made sure the modernist architecture of the museum, which is directly across the street from Kelly Ingram Park, adjacent to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and beside the A.G. Gaston Motel, didn’t dominate the pre-existing buildings so instrumental in telling the story of the Civil Rights Movement.

Curry notes the building serves as an “ode to classical architectural idioms, but it's also a nod towards a refreshing modernist gaze by pushing this community into kind of the next period by experiencing an architecture that's more contemporary.” The Institute launched in 1992 as a locally-focused history museum and an international center for civil rights research—it continues to be a leader in social justice education today.

The three buildings, each showcasing a different architectural style, highlight not only the perseverance of their makers but that of a community that fought tirelessly and continues to fight for social justice. These Birmingham landmarks showcase why the preservation—and ultimately the experience—of these places is essential to telling the country’s history and propelling us to a brighter future.

“These buildings represent the ingenuity and creativity of Black professionals and a community to manifest their dreams," says Leggs. “Through historic preservation, there is the opportunity to regenerate this powerful legacy and community vision as a way to revitalize that historic neighborhood and continue the important work of uplifting visions of Black America."

You Might Also Like