I decided my sister should die after an accident – now I’m filming people’s last moments at Dignitas

Fifteen years ago, I stood in a hospital room in France as doctors gave my much loved elder sister a sedative before removing the apparatus that was keeping her alive. A few minutes later she stopped breathing, and even as I write this all these years later, my eyes well up with tears. I miss her every day.

As she had gently trotted round a training ring, Hilary, then 66, had been thrown off the horse on which she was having the last of 10 riding lessons. She was wearing a helmet but the fall broke her neck at the highest point possible, her C1 vertebra. She survived, thanks initially to the teacher giving her mouth to mouth resuscitation until the paramedics arrived, but once she had been stabilised at the closest hospital, it became clear that she would require mechanical respiration with a tube through her neck for as long as she lived. In addition to being unable to speak, she would be tetraplegic, in all likelihood dying from pneumonia or some other infection within a few years at best.

The doctors asked what we, her family who had gathered from around the world, thought she would want, since she was in no state to communicate her own wishes, and we agreed by a majority of three to one that what lay ahead for her was no life she would or could accept. We gave the go-ahead for them to switch off the machinery and in so doing, to end her life. This was not an assisted death as such, but there is no question that as a result of the decision we took that day, a few weeks later we would gather at a crematorium in north London for her funeral. In that sense, we killed her.

And here I am now, standing in a room at Dignitas, in an industrial estate on the outskirts of Zurich, filming the last moments of another woman’s life. It’s been a long, emotional journey and I can only hope it will be worthwhile.

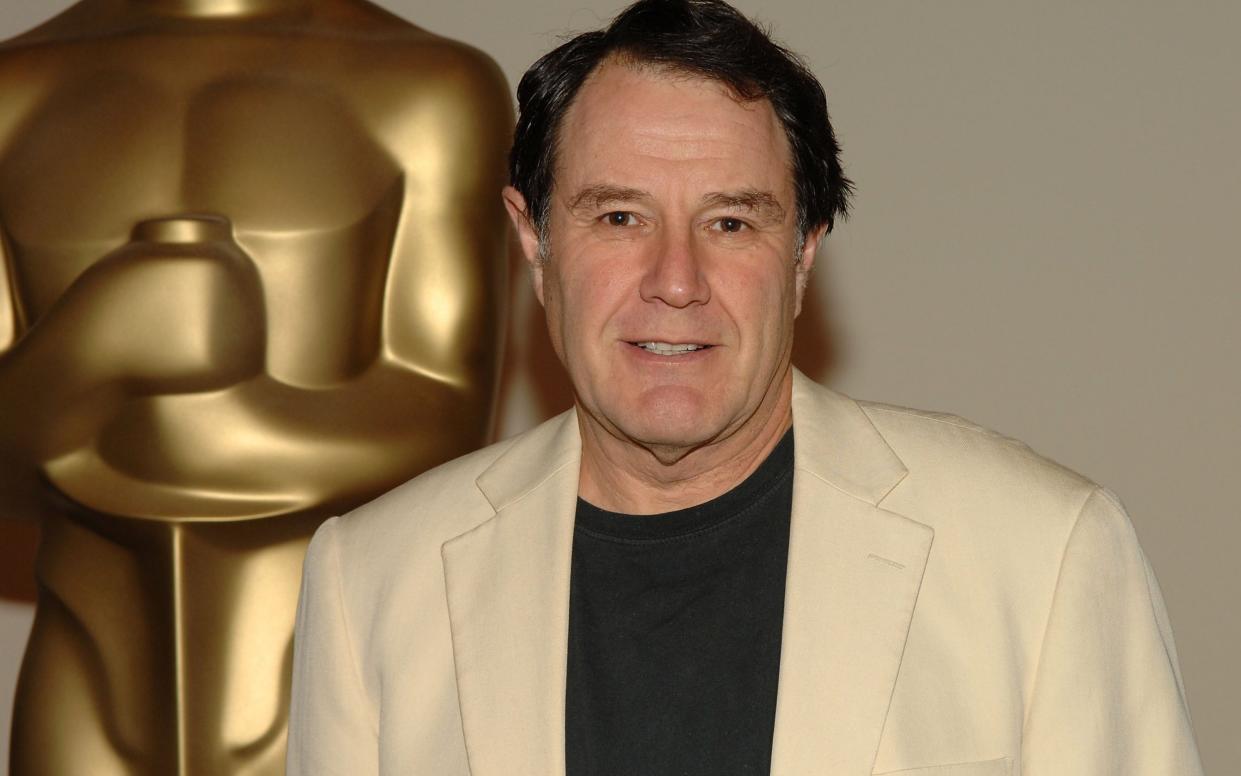

A Time To Die, my latest feature documentary, was not my idea, but when the production company approached me, I didn’t hesitate.

I was aware of the ongoing debate around the contentious issue of whether the current law on assisting someone to die should be changed. As it stands, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, helping someone to die can lead to a 14-year prison sentence. Last month, the Isle of Man took a step closer to becoming the first part of the British Isles to legalise assisted dying after its Parliament gave a second reading to an Assisted Dying Bill. In Westminster, Parliament has debated changing the law three times in the past decade, and in 2015, MPs voted against the legalisation of assisted dying in England and Wales.

Currently, if you help someone to end their own life, there will most likely be a police investigation. While the circumstances will be taken into account when determining whether it is in the public interest to prosecute, you will probably be interviewed under caution, your home may be declared a crime scene, and it can take months or even years of living with a jail sentence hanging over you for a decision to be taken. All of this at a time when you are probably in the midst of grief.

This has to be one of the most difficult, personal and emotionally trying programmes I have made in a 50-year career reporting on wars and making documentaries. It took me deep inside the lives and deaths of people wrestling with wretched choices. People like Dan, 47, a former music teacher now living with multiple sclerosis, who continues to compose music on his laptop using movements of his tongue and nose, which are picked up by his screen. Dan now lives back with his parents and is getting his Dignitas paperwork in order – or as he calls it, “his get-out-of-jail free card”.

We spent time with Di and Trevor, a couple whose plans for a far-flung retirement travelling the world were halted when Trevor developed motor neurone disease. Unable to speak or eat, and in constant pain, Trevor used an iPad to answer my questions. At one point, he held up the words: “Utter boredom, pain, both actual and emotional.”

Under the circumstances, it was really quite remarkable the freedom our contributors gave us to record their lives, and in some cases, their deaths, and I suppose that must say something about our having convinced them of our ethics, along with our promise to respect their wishes throughout, and our genuine concerns for their welfare.

We negotiated rare access with Switzerland’s best known assisted dying organisation, Dignitas, and through them we contacted their 1,300 UK members, some of whom had joined because they sympathised with the cause, others because they might want it as an insurance policy for use at an unspecified later date, and others because they had a more immediate desire for an assisted death. We considered how best to negotiate the ethical and moral dilemmas of what to show and what not to show, and in this respect we were guided not only by Ofcom’s strict regulations but more importantly, by our participants’ own wishes.

Kim and Andy, a couple who met at her university in Manchester, got in touch and invited us to document their life since Kim’s diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a rare neurological disorder.

Kim, a fiercely independent woman throughout her life, was so appalled by her deterioration that she was adamant about wanting to travel to Dignitas. Now reduced to using words sparingly, she gave it to me straight: “I will take a drink. I will die – hopefully painlessly.” Right from the beginning, they were both extremely willing to have us follow them the entire distance, however it unfolded. Indeed, we genuinely didn’t know if Kim would change her mind until we filmed the family packing up the car. Even then she might have decided to come home, right up until the point she finally took the drink that would kill her.

I gained so much from witnessing the compassion, care and love between the people who allowed us in at the bleakest point of their lives. It’s not easy getting up in the morning to go to work knowing that in all likelihood there will be a moment when the tears simply can’t be stopped. So, why, at an age when most of my peers will have retired, did I do it?

I felt ultimately that the best service we could provide our audience with was to coolly and neutrally show examples of those most affected by the law as it stands now, while highlighting fairly and honestly what it is that those who oppose any change most fear.

And if we could pull back the curtain to show just what is involved practically with an assisted death, as well as what it is like if you don’t get one, or take matters into your own hands, that might just make a difference to their understanding of the issue.

Having heard from around 150 active supporters of assisted dying, we approached numerous opponents to hear their side of things. I was surprised by how few ultimately agreed to take part. The Archbishop of Canterbury was too busy, two noted palliative care professors at first seemed willing, and then essentially ghosted me. A high profile religious opponent who had organised numerous demonstrations against a change in the law was also too busy to talk to us. A GP who had sincere views against a change in the law based on her concerns for her largely Muslim patients was forbidden by the partners in her practice from giving us an interview. Another consultant was told by her hospital trust not to put her head above the parapet.

In spite of this, we wanted to let the audience decide which side they favour most. This debate is too often driven by anecdotes, in some cases quite horrific ones, which are brandished like weapons by the warriors embedded in the trenches of either side.

On this issue, you can’t have it both ways, but what you can do is try to walk a mile in another person’s shoes, and maybe that will help you decide what you think is right in a just society that cares for its citizens.

A Time To Die airs on Monday November 13 at 10.45pm on ITV