My dad at 101: The busy first year of a New Hampshire centenarian

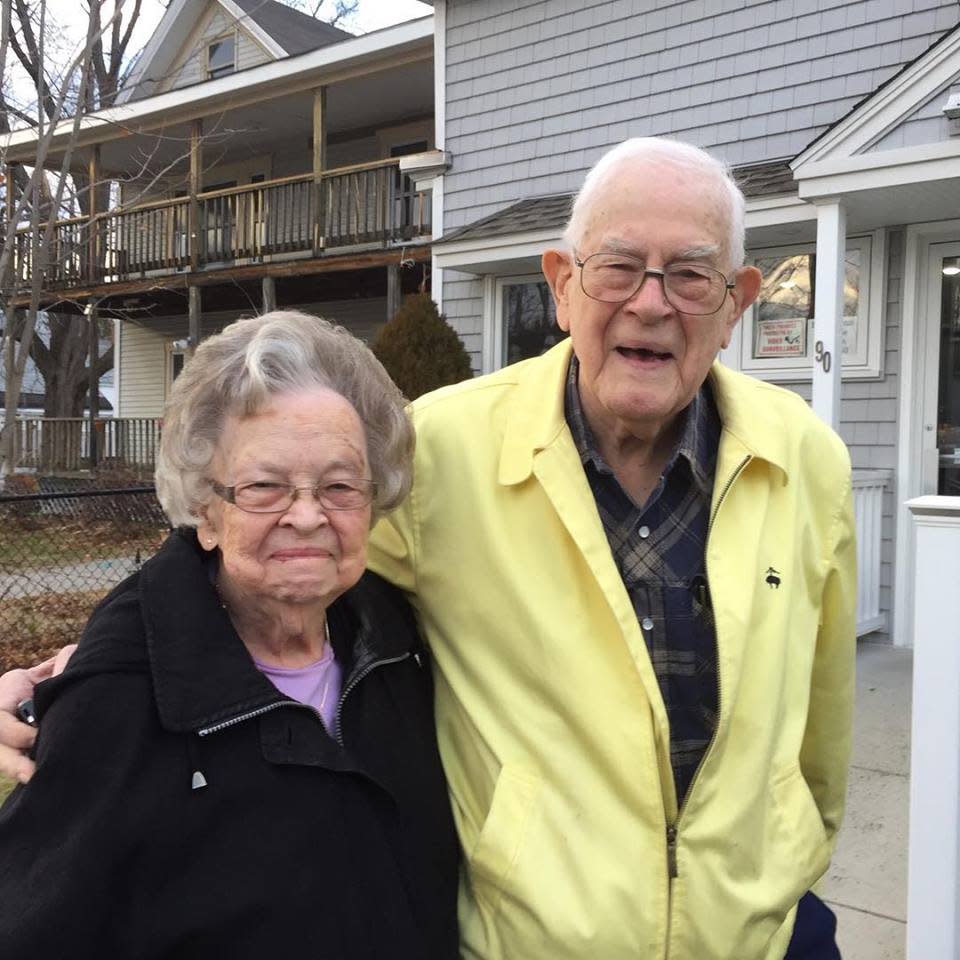

At this writing the oldest living American is Elisabeth Francis of Houston. She’s 114. My father, John B. Robinson, is a spring chicken by comparison. He turned 101 last month. The Inn at Edgewood staff threw a lively celebration. Gary “Creekman” Sredzienski brought his accordion and Portsmouth Mayor Deaglan McEachern read a dedicatory speech.

A few years ago, out of the blue, dad put himself on a keto diet. That means a lot of protein and almost no carbs. He also swore off cake, cookies, ice cream and candy.

“Not a problem, “ Wendy Switzer said. She's the new administrator of the small assisted living facility off South Street in Portsmouth. It once was an inn, tucked up under the pines off South Street. The building now houses nine residents. They call it a “community,” but the intimate setting is more like a family. The newest resident turns 105 this fall.

Wendy's keto-friendly birthday cake was the hit of the party. "Not bad at all,“ everyone agreed. The same could be said for my father's first year as a centenarian.

He tends to downplay the negative stuff including two recent surgeries and two minor tumbles. Last year at this time he was wrapping up 33 radiation treatments, giving him the dubious title of “the oldest cancer patient at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital.” The Dover hospital presented him with a cake for his 100th birthday in 2023. But it wasn't keto-friendly, so he gave it to the staff where he was then living in Durham.

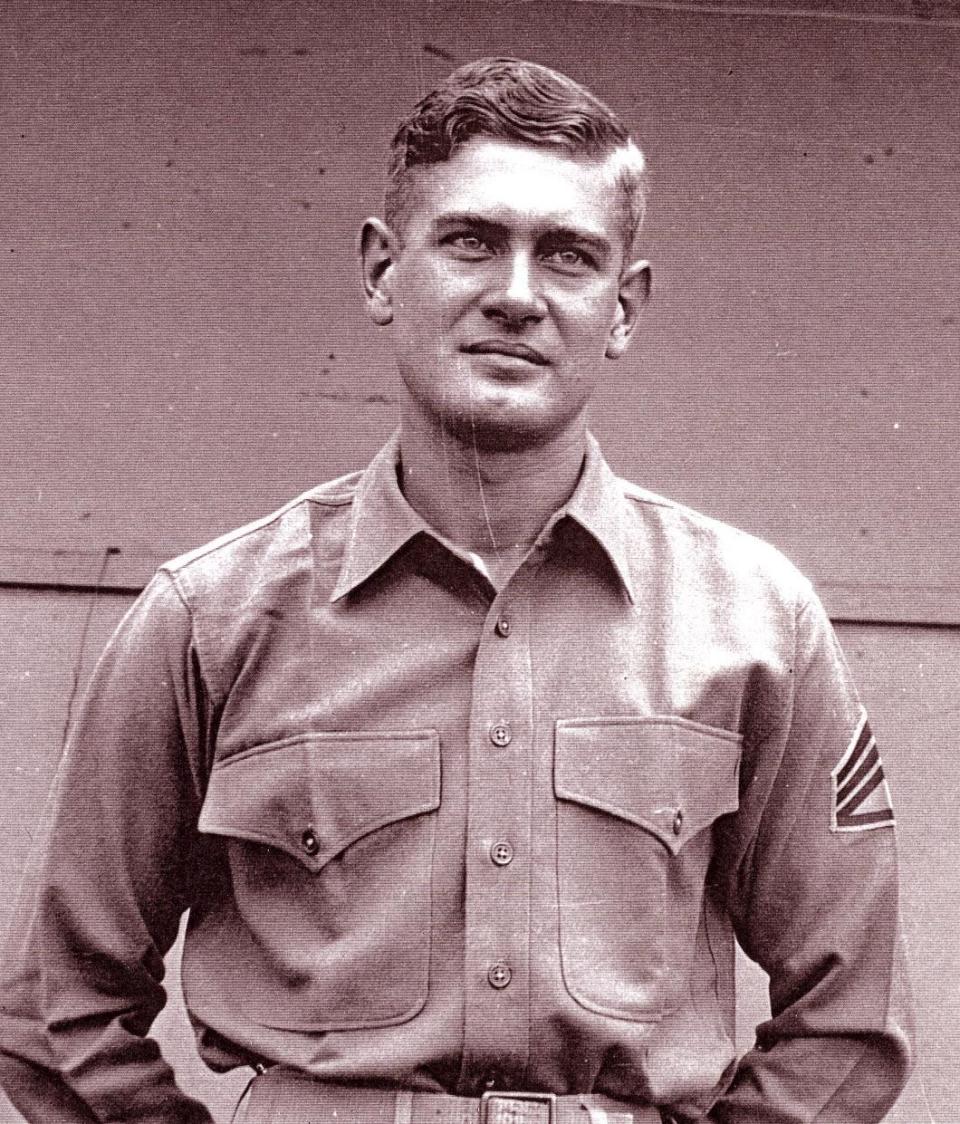

Dad jokes that his latest healthcare adventures are nothing compared to his emergency appendectomy aboard a battleship in the Pacific during World War II. His four years as a U.S. Marine, including service at the Battle of Iwo Jima and in secret missions with the “Beach Jumpers" are ancient history. (See “When your dad turns 100.”) He'll tell those stories if you ask. But his focus is on today, especially what's for dinner, the book he's reading, the weather, the news, and whatever project is spread out on his work table.

He works from a card table tucked in a corner of the living room just inside the entrance. A model airplane builder from age 8, he now specializes in assembling 3D paper figures of animals, birds, ships, and holiday decorations. He downloads the designs on his Chromebook and runs the paper sheets from a color printer at a small desk in his small comfortable room just down the hall.

Last week dad gave a class at the big table in the dining room. Eight Edgewood residents folded, twisted, and glued eight paper rabbits. The class lasted three hours. “They weren’t exactly rapid rabbits,” Dad told me, “but we took our time and everyone took a bunny back to their room.” His masterpiece, a feathered eagle with wings spread, took weeks to construct from 39 sheets of paper. It stands proudly on the living room mantle today.

Did I mention dad suffers from an essential tremor? Cause unknown. It makes holding a fork or a cup of coffee tricky. But when he picks up an X-Acto blade, a miracle happens. His right hand becomes as steady as a rock, allowing him to carve out the most intricate details for his paper sculptures. For half a dozen years now, he has been part of a clinical study that started at Columbia University. He undergoes a two-day battery of cognitive tests every 18 months. The study is managed by a university in Dallas, Texas. Dad is a proud card-carrying “brain donor” who will give his gray matter to science.

I drop off books and craft projects, when possible, but he goes through them like a house afire. We’ve done just about every 3D puzzle from a three-foot tall Empire State Building to St. Paul's Cathedral to a soccer-ball-sized globe of the Earth. The latest project was a working model of a V-8 engine, a wooden race car with pistons operated by rubber bands, and a giant spider held together with metal screws. He’s caught up with police thrillers by Archer Mayer, sci-fi novels by Andy Weir, and he burned through five texts on quantum physics.

When I phoned in recently, dad said he was too busy to talk. “We’ve got a dying project going on here,” he said, then paused for comic effect. “Not that kind. We’re dying table napkins different colors. I’ll call you back later.”

For the record, my father never drank alcohol or smoked, but worked his butt off. He worked 30-odd years for AT&T and is pleased to have beat the system, having been happily retired longer than he worked. If you’re looking for the secret to longevity, you probably won’t find it here. A New York Times essay on “Super-Agers” found no correlation between diet, exercise, and resistance to age-related decline. Staying active and having strong social relationships may be part of the equation, but it seems to come down to genetics and a “lucky predisposition,” whatever that is.

When my father was born in 1923, life expectancy for an American male was 56.1 years. Today that figure has risen to 73.5 years. At this writing I am 73.2. The good news is that I may also have won the genetic lottery. Time will tell. The downside, based on my Portsmouth property tax bill, is that I will never ever retire.

The toughest part of the aging process, we’re learning, is money. We assumed selling the family home was the key to financial peace of mind. We hadn’t anticipated that the monthly rental at a corporate assisted living facility would shoot up by over 60% in five years. We were surprised when an oral surgeon insisted my father had to pay $11,000 in advance of any treatment. When dad moved to Portsmouth last year, a chain bank in town refused to honor his new address unless he showed up in person to prove his identity. Although he has been out of military service for almost 80 years, dad has yet to receive veteran’s benefits. I think he’s due.

It's a pretty scary world out there at any age. There are scammers around every corner ready to rip off the elderly. They pose as government officials, grandchildren in distress, fake lottery agents, computer technicians, even Medicare advisors. So far, we've only been hit by one scam, and escaped unscathed.

But there are still angels. Back in the 20th century, I had done a little work for Patricia Ramsey, then owner of the Edgewood Center. It had been decades, but last year I called her for advice.

“We have an opening at the inn,” she told me. “It's a small room. Would your dad like to see it? “

Pat offered to pick up my father and drive him to Portsmouth to check out the room. I went in one day and he's reading a book about quantum physics, “ she says.

Dad liked the room but asked to have the TV set removed. He's too busy for TV. Almost a year later, he loves this intimate and affordable facility. He praises the staff, and adoores the food. He gets three homemade keto-friendly meals a day. He can see the kitchen from his door. Life is good.

As I was wrapping up this article, the phone rang. “I'm just back from the doctor,“ dad reported, clearly upbeat. “All the doctor had to say was ? Everything looks good. I'll see you in a year!”

J. Dennis Robinson is the author of over a dozen books and 3,000 published articles. His latest works are Portsmouth Time Machine (with illustrator Robert Squier), a richly illustrated hardcover history of New Castle island, and "1623: Pilgrims, Politics, Pipe Dreams and the Founding of New Hampshire."

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: My dad at 101: The busy first year of a NH centenarian