How the Creators of Blackberry Farm Blend Luxury and Nostalgia at Their New Mountain Inn

Eighteen months or so ago, the idea of a multigenerational summer camp appealed about as much as a cremated campfire marshmallow. A residential regime of collective endeavor and relaxed, firefly-filled evenings under the stars sounded like a sleepy 1950s throwback. But after months spent in genuine confinement with close relations, honing our skills at charades, many of us have emerged with an unexpected appreciation for simple family time.

A new type of luxury resort aims to capitalize on this urge for nostalgic togetherness. High Hampton, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina, is the latest venture from Sandy Beall and his family, owners of the celebrated Blackberry Farm and Blackberry Mountain retreats, on the other side of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in eastern Tennessee. Beall is betting that, as the world begins to open up, those itching to travel will choose domestic destinations designed for family bonding instead of clocking up countless air miles on the hamster wheel of European capitals.

More from Robb Report

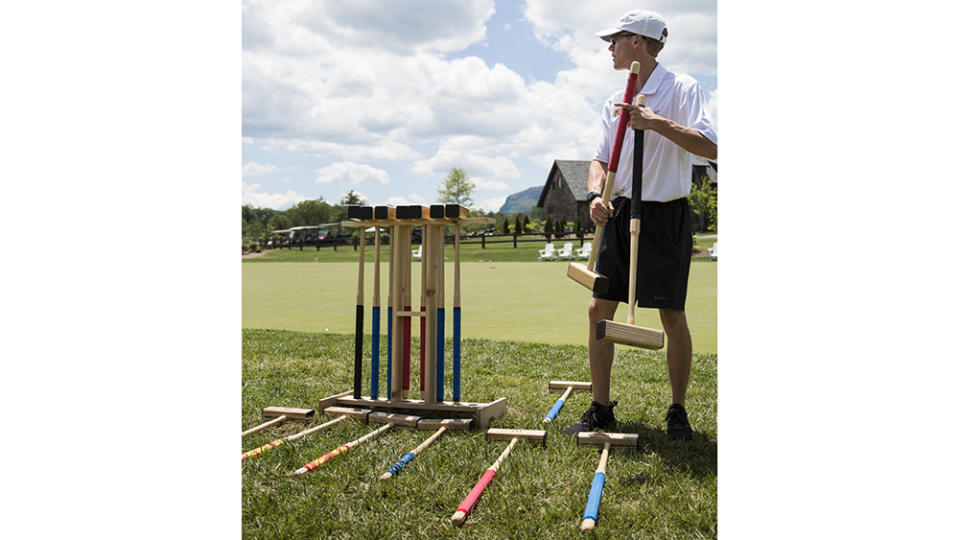

When Robb Report visited High Hampton, just outside the small town of Cashiers, in May, it was shortly after the historic property reopened following a three-year overhaul. The resort was gearing up for a season of distinctly traditional summer-camp fun, complete with bingo, croquet and kayaking, but with the sumptuous cuisine, forensic attention to detail and exceptional service for which Beall family properties are renowned. If the Farm is Southern pastoral perfection and the Mountain is the pinnacle of elite wellness, the reimagined High Hampton is wholesome Americana distilled.

Ball & Albanese

The summer camp schtik is nonironic; this is not a hipster hotel for jaded Brooklynites looking to skewer country-living clichés. “There’s no hatchet-throwing,” as one staff member put it. Beneath the chic upgrades, the resort exudes the spirit of Dirty Dancing; in fact, in 2016, the hotel (under its previous ownership) stood in for Kellerman’s resort in a TV remake.

The idea of a high-end camp is not new, but the genre has faded from fashionable view since the decline of the faux-rustic summer palaces of Gilded Age industrialists, known as the Adirondack Great Camps. High Hampton fits into this tradition of bucolic retreat but stops short of full Marie-Antoinette-as-shepherdess cosplay. Its new owners take authenticity extremely seriously. A more accurate comparison in terms of philosophy and style would be the National Park lodges created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, though with a basting of rich Blackberry sauce.

Beall himself, spry and softly spoken, first tried to buy High Hampton nearly 40 years ago. “I play a long game,” he says, repeatedly. Back then, he recalls, the owners were not ready to sell. “I’d had homes up here since the early ’80s,” he says over coffee in one of the inn’s many well-upholstered nooks. “We inquired about buying it again in, I think, the early ’90s. So I always had a love and affection for the property.”

Beall dictates business mantras with a staccato delivery, his commitment to incremental improvements unrelenting: “We have this saying: ‘Good, better, best, never let it rest.’ But it’s a process. Every year gets a little bit better. You never let up. Constant change. Don’t confuse habits with wisdom, and just never stop improving. That creates magic.”

Ball & Albanese

His staff buzz around him like attentive moths to a flame, discussing progress on soundproofing (wonky old floorboards mean gaps under the doors) or water-pipe repairs. He’s keen to weigh in on every detail, including the habits of local birdlife (a spate of window-pecking by male northern cardinals attacking their own reflections).

The son of a nuclear engineer on the Manhattan Project, Beall and his four siblings grew up in Knoxville, Tenn. Now 70 years old, he got his start in business at 18 while waiting tables at Pizza Hut in college, quickly winning a promotion to store manager. The owner sold his franchise and awarded Sandy a sum to invest in his own restaurant. In 1972, Beall, then just a college sophomore, opened the first Ruby Tuesday, which eventually grew to a global chain of nearly 900 restaurants. Beall remained at the helm until he left the company in 2012.

In 1976, he and his then-wife, Kreis, bought an old inn, Blackberry Farm. The couple lived in two rooms and, to pay the mortgage, rented out the rest to two local banks to entertain their employees and clients. The inn opened to the public in 1990. Beall took the Ruby Tuesday mass-market model and simply elevated it for a wealthier clientele. “Hospitality is hospitality, whether you’re charging $20, $200 or $2,000,” he says. “Now, depending upon who the customer is, from a demographic standpoint, your menu would be tweaked up; the quality of the ingredients, the level of execution, the level of the room would be different.” Other than adding a zero or two, he says, “it’s really the same business.”

By this time, the couple had two teenagers, Sam and David. Early on, Beall divided his assets between his sons, giving Blackberry Farm to Sam. Before his death in a skiing accident in 2016, Sam, a chef and father of five, had transformed it from a genteel local favorite to a trendsetting, world-class culinary destination. Today, it’s the kind of place where you can go foxhunting, consult with the resident beekeeper and buy a $1,100 jigsaw puzzle. Beall remains involved, advising Sam’s widow, Mary Celeste Beall, who took over as proprietor after her husband’s death. In 2018, she oversaw the opening of a high-octane wellness outpost, Blackberry Mountain.

Ball & Albanese

Beall is at pains to point out that, while Blackberry is “a big business” run by “an executive team of a dozen people,” the success of all his resorts ultimately derives from their family structure. After Mary Celeste, he says, the future proprietor “will be one of the children; after them, another child.” Theirs is the kind of patriarchal clan that has largely faded from a culture in which grown children are accustomed to deciding their own fates.

At High Hampton, the latest addition to the family portfolio, most guests appear to be in comfortable retirement, and many have been coming for generations to admire the award-winning dahlias and resident donkeys, Ed and Fred. From 1855, the property was the summer hunting retreat of the Hampton family, wealthy planters from South Carolina. Their most famous scion, Wade Hampton III, was a Confederate general who was reputedly one of the largest slaveholders in the South and, when Reconstruction ended, served as governor of South Carolina and then as a US senator. In Gone with the Wind, Scarlett O’Hara’s first husband, Charles Hamilton, serves in Hampton’s regiment.

The estate passed in 1890 to Hampton’s niece, Caroline. After her death in 1922, it was bought by Gertrude Dills McKee, who later became North Carolina’s first female state senator, and her industrialist husband, Ernest Lyndon McKee. They turned the property into a family-run mountain golf resort, and so it remains.

Arlington Family Offices, a wealth-management company that serves affluent families, bought High Hampton from the McKee family in 2017, and its CEO, Ken Polk, an old business associate of Beall’s, brought him on board. The Beall family now owns the majority of the hotel. “It’s easy to negotiate with like-minded souls,” Beall says. This is a phrase he uses a lot. If you can’t be family, like-minded souls are the next best thing. It also represents the ethos of High Hampton’s membership club, which operates on-site residences and sporting facilities, and which is owned by Arlington and managed by a local developer, Daniel Communities. The founder of the latter is an Arlington client. Everyone is most definitely keeping it in the family.

Ball & Albanese

Which is not to suggest High Hampton is some sort of hobby for a group of buddies. Beall is no gentleman dabbler. “I’ve lost plenty of money in my life. And I’ve made a decent amount of money,” he says. “Every time I invest in something outside of my core competency—what I think I do well—I lose money, and I think I do it over and over sometimes just to remind myself how dumb I am in certain areas of my life. And I always come back to what I do well. But I’d say a good way for a wealthy person to lose money is to open a hotel, a restaurant, buy a big boat, things like that.”

Since the inn opened in April (room rates start at $595 off-peak), guests have been able to use the club facilities, but the general public, who once flocked to High Hampton for the Sunday fried-chicken buffet, are no longer invited. Owning real estate on the property is required for club membership. For some of those who already had homes there, the transition to the new upgraded club presented a challenge. “I think anytime there’s change, the first thing in people’s minds, they think negative,” says Polk. “I think the real key was when Blackberry got involved.” Mary Celeste talked to club members, says Polk, and she “just put it to rest.”

The inn upgrades were managed by Blackberry’s design unit, whose task was to overhaul what had become a faded midmarket hotel. The work included removing plastic replicas of the original 1930s bark shingles from the exterior walls and replacing them with new, genuine bark. Inside, the dark-wood lobby is punctuated by clusters of chairs in leather and velvet, floral sofas, rattan tables and vases of flowers. The effect quietens the further you explore, ending in a lovely room with a four-sided fireplace centerpiece and a grand piano overlooking the lawn.

Ball & Albanese

Upstairs, the aim was to embrace what Scott Greene, the inn’s general manager, calls the building’s “quirkiness and eccentricities” while adding modern accents and air-conditioning. The main lodge’s 24 original guest rooms were combined to create 12 larger ones, which retain a rustic cabin feel updated with modern art and bright quilts made of sari material. The art and furnishings are designed to look relaxed, not over-curated, says Greene. “Some country hotels are very tightly themed,” he says. For example, “they’ll have a room named after a wildflower, and it will only contain pictures of that wildflower. We are more eclectic.”

An additional six buildings housing 40 guestrooms, plus three cottages, are scattered around the grounds, each with its own little verandah with red-painted rocking chairs and views of the manicured grounds, stocked with old trees and hot-pink puffs of rhododendron. Neat rows of parasol-topped daybeds line the back lawn, which runs down to a 35-acre lake, framed by two wooded hills, Rock Mountain and Chimney Top. The 1,400-acre estate includes 15 miles of hiking trails, a new 18-hole golf course designed by Tom Fazio, tennis courts, a pool, gym, croquet lawn, kids’ club and a handful of bars and restaurants. A spa occupies the third floor of the inn and is run by a motherly team (all High Hampton staff display a tender concern for guest welfare that is sweetly maternal).

The Dining Room, with blue glass chandeliers and vases of mountain laurel and ranunculus, hosted nearly 100 guests and club members on an off-season Monday night but never felt noisy or crowded. The meltingly delicious braised lamb with horseradish and pea puree was a standout, while the coconut cake has developed an obsessive following, according to its bashful creator, pastry chef April Franqueza, who, with her husband, executive chef Scott Franqueza, joined High Hampton from Blackberry Mountain.

Scott, who trained in classic French cooking at Café Boulud, and in Michelin three-star contemporary French and American cuisine at Per Se, both in New York, before pivoting to Blackberry’s farm-to-table style, is now trying to bring the best of all three approaches to High Hampton. Once, he says, he would have assumed that fine dining meant a “23-course tasting menu, white tablecloths. Not anymore. I just want food that’s approachable, seasonal and of the highest quality.”

Ball & Albanese

One challenge the chefs were worried about was the willingness of existing club members to embrace anything experimental. The old buffet, a smorgasbord of Southern favorites served morning, noon and night and trenchantly consumed by its devotees for decades, was abolished in favor of à la carte dining and is spoken of by current staffers with something of a shudder. Their fears were largely unfounded, says Scott, whose lunch menu includes kale-artichoke pizza and Verlasso salmon with pistachio pesto. “A woman introduced herself to me the other day… who said her kids were raised off the buffet,” he recalls, implying that he expected to be chewed out. “She just said, ‘Thank you so much for redoing it.’ She said there are some owners that are kicking and screaming about it, but she’s like, ‘The change is welcome.’”

According to Tony Snoey, the club’s general manager, 233 of the existing 250 homeowners bought back into the new club, paying a discount on the $100,000 initiation fee (which has since increased to $125,000). Annual dues, which cover the family, are an additional $14,500. A further 178 lots were made available and are now nearly all sold, with the few remaining parcels starting at $775,000.

Polk estimates the average age of the existing members as early 70s. But after the acquisition, “we saw that the average age went down by 15 to 20 years pretty quickly,” he says. New members are trending younger partly because of the Blackberry appeal, partly because more families are choosing to work remotely from a second home. Polk, who specializes in generational wealth, also says younger people now have more disposable income. Some of his Arlington clients are in their late 20s. “Because of technology and software, there’s been this wealth that’s been amassed at a much younger age,” he says.

Ball & Albanese

For the first time in its history, the resort will be open all year, a departure for a strictly seasonal area. “I think a lot of people are looking to their Cashiers home to be year-round,” says Snoey. New families are “putting full offices into their homes, sometimes dual offices for both the spouses,” he says, noting that High Hampton is capitalizing on a fundamental reordering of family priorities. “Covid has driven the family unit together. I think parents are realizing that going into the office for 80 hours a week is just not as important.”

Despite the encroachment of a modern WFH lifestyle, standards of etiquette remain traditional. One waitress who inquired of a male guest if he was going in to dinner was met with the affronted response, “I am not dressed for dinner.” That’s because jackets are required for the evening meal, where men pull out chairs for their wives, in heels and lacy cocktail dresses, and ultra-groomed daughters, in silky strapless frocks. (Daytime, the look is much more casual: think pickle-ball-appropriate leisure-wear.)

Outside the enchanted circle of members and guests is a green-eyed local community. The inn now employs a gatekeeper to redirect the curious. The Franquezas report that their neighbors in the nearby town of Sapphire have nevertheless exhibited an abundance of Southern hospitality. “You come home and there’s flowers on your doorstep from our neighbors,” reports Scott, who hails from Massachusetts. Such niceties, it seems, did not happen when he was working in New York.

April, who is from Virginia, characterizes Southern culture as “open-door policy,” saying, “It doesn’t matter how close or far you live from someone, they’re your neighbors.” Scott agrees: “I think you hit that Mason-Dixon Line and it just starts. It’s like a step back in time.”

Ball & Albanese

Beall expects the clientele to remain largely a “drive-in market,” in contrast to the Blackberry properties, which are a “fly-in market.” “There are few places like this for what I’d call the Southern markets,” he says, explaining that the vibe is right for the moment.

“It’s very much a mountain camp—an adult camp with golf and hiking, and everybody coming together at meals and having fun and talking. It’s about family traditions.”

His own family has evolved, and after a divorce he is now remarried. He and his new wife, Suzanna, were dividing their time between New York and Florida but decamped to Tennessee mid-pandemic. Beall estimates he has owned more than 50 homes in his time, and he likes to change them at a rapid rate. “I love everything about a home,” he says. “Silver, fabrics, the design, I love everything about it.” The couple have built by Blackberry Mountain and regularly visit Wyoming, where Beall is involved in Snake River Sporting Club, one of “about a dozen hospitality businesses” in which he has a substantial stake.

At High Hampton this summer, families will get together for a doubles croquet championship and a Stars and Stripes kids’ camp, before ending the season with a Battle of the Paddles pickleball competition on Labor Day. But will this nostalgia for retro family vacations last, or will we be on the next plane to Bhutan, solo, come 2022? One staff member says that Beall has an “uncanny” ability to anticipate what will be fashionable in 10 years’ time. Beall’s take on the subject is decidedly more ambitious: He says he prefers to plan ahead “50 years, 100 years, not 5 or 10.”

Ball & Albanese

In Dirty Dancing, which is set at the dawn of the ’60s, Max Kellerman, the owner of the aging resort, laments the end of an era: “You think kids want to come with their parents and take foxtrot lessons? Trips to Europe, that’s what the kids want. Twenty-two countries in three days. It feels like it’s all slipping away.”

We’ve come full circle. At High Hampton, they’re bringing back bingo, if not buffets, because that, not trips to Europe, is what people want now. At least, that’s what Sandy Beall is betting on, and he plays a long game.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.