COVID-19 Is Killing With More Than Just a Virus

Shon Myers and Claire Hanley grew up in the same, small Maine town. It wasn’t until last fall that they reconnected, at 43 and 37 years old, via the dating app Bumble. When they met up again in October, Meyers revealed to Hanley that he was a recovering heroin addict. Although he’d relapsed before, as 40-60% of people in recovery do, he was attending daily meetings and felt strongly that this time was different.

“Shon had a year of sobriety under his belt and seemed very much committed to it,” says Hanley. “His family even said they'd never seen Shon so dedicated to being sober.”

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. As Portland, ME, and the rest of the country began to shut down in mid-March, Hanley worried what Myers would do when he couldn’t attend his daily in-person meetings. But when she tried to broach the subject, Myers seemed unwilling to accept that a program so essential to so many people would be included in the growing number of school, office, and other business closures.

“But a week or two later, they closed the buildings that were holding the meetings,” Hanley says. “There wasn’t a lot of information.”

Since Myers wasn’t a “techie person,” according to Hanley, she offered to show him how to use the video conference service Zoom so he could continue participating in his meetings online. But after a couple attempts, Myers got discouraged. “It’s not the same,” he told Hanley.

“Shon was a fisherman, a very salt-of-the-earth-type person,” she says. “He relied on that in-person connection, handshakes, hugs. He had a lot of friends in the Portland recovery community. It was almost like his church. So I think he missed seeing his sober friends.”

Those feelings of isolation coupled with the stress over his finances—with restaurants closed, there was little demand for fresh seafood—is what Hanley believes caused Myers to “unravel.” In the weeks they spent quarantining together at Hanley’s home, she noticed him growing increasingly quiet. “It was like there was something going on in his head all the time,” she says.

The Saturday before Easter, however, Myers seemed to be in lighter spirits. They’d spent the morning in Hanley’s backyard playing with her son Charlie. She’d snapped a photo of them together, Myers sitting in an azure lawn chair with Charlie perched high on his wide shoulders, the two of them smiling with Ted, Hanley’s 12-year-old terrier mix, curled up on Myers’s lap.

Later that afternoon, Myers said he was going out to grab some clothes from his apartment and check on his mom before returning to Hanley’s place. Around 3:30 p.m., he texted Hanley that he was also going to swing by Trader Joe’s to grab some flowers for her and his mom to celebrate Easter the following morning. She remembers the last text he sent her, on April 11, 2020: "Ugh. Never mind. Line is around the block. I guess no flowers then. I'm leaving. ??”

Hanley laid down for a nap with her son, but when she woke up Myers still hadn’t returned. She texted him, but he didn’t respond. Because he’d been upset, she thought maybe he’d just needed some space to cool off and told herself not to worry.

Two days later, on April 13, she got the news she’d been dreading. Myers, a recovering heroin addict with a year of sobriety under his belt, had relapsed and died. The failed trip to Trader Joe’s seemed to be the final nail on the coffin. Were it not for coronavirus, Hanley believes her boyfriend would still be here today.

“With an addict like that, I know there's no guarantee he would have never relapsed,” she says. “But I don't think he would have relapsed right now. I do think he would still be alive.”

A Mental Health Crisis In Full Swing

As Americans hunkered down at home this spring, a perfect storm of boredom, loneliness, and heightened anxiety began to set in. In addition to the fear of catching the virus itself, industries across the board were crippled. In Maine, the service, leisure, and hospitality industries—which would directly impact the demand for the fresh seafood Myer’s spent his days catching—were hit the hardest. Nationally, the number of out-of-work Americans hit a historic high, with 36 million people filing for unemployment in the first two months of the pandemic alone. In a survey published by the National Endowment for Financial Education in April, the month Myers died, nearly 9 in 10 Americans report feeling anxious about money. Job security, income stability, and being able to pay bills including utilities, rent, and mortgage are among the top concerns. Even the extra $600 of unemployment that has offered some financial relief is temporary, with an end date scheduled for later this month.

Experts have warned of the lasting effects this unprecedented time will have on our mental health; already, a historic number of people are reporting an increase in symptoms of anxiety and depression related to the pandemic.

“We are creating a mental health crisis that is absolutely in full swing and seeing so many people overdose, relapse, die by suicide,” says Ashley Loeb Blassingame, co-founder of Lionrock Recovery, a telehealth drug and alcohol addiction rehab program offering outpatient treatment online. “You name it, it’s happening.”

A post shared by Ashley Loeb Blassingame (@mcloebin) on Jun 23, 2020 at 2:34pm PDT

Myers is one of a yet-unknown number of people who have relapsed since mid-March, when stay-at-home orders went into effect for the majority of states in an effort to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. At least 35 states have reported an increase in opioid-related deaths, according to the American Medical Association. And sales numbers show that many Americans have been turning to alcohol and other substances as a way to cope.

In normal times, people in recovery might combat their triggers in a productive way by going to a meeting with their chosen support group, working out their stress in the gym, or meeting a friend for coffee and a chat. But with everything closed, all of these outlets were off the table. This left many, like Myers, feeling lost and desperate.

“Relapse is up,” Blassingame confirms. “The number of people who are seeking treatment is up. We have 600 clients in treatment right at this moment. We’ve tripled in the last three months. ”

Though more Americans are becoming familiar with the concept of telehealth thanks to pandemic-related necessity, Lionrock has already been in the business for a decade, long before the concept of seeing a doctor virtually was normalized. Virtual counseling sessions geotagging to ensure patients are where they say they are, online support group meetings, and remote drug testing are among the tactics Lionrock’s nation-wide network of therapists use to help patients achieve and maintain sobriety. In response to the pandemic, Blassingame and her team also decided to offer a free support group and online tools for anyone who might be struggling with the ongoing crisis. Unlike traditional treatment options that rely on making in-person connections, Lionrock was well-positioned to handle the immediate influx of people seeking their services.

“The COVID-19 piece has been a really strange world for us because, almost overnight, everyone in the treatment business came into our sector,” says Blassingame. “It’s these same treatment centers that told us for years what we were doing was never going to work. But actually, telehealth makes treatment more accessible.”

“My Brain Went to That Place”

Emily McAllister has been sober since September 25, 2009, and is in an active 12-step recovery support program. When the pandemic hit, she felt fine—at first. Her program encourages a “one day at a time” approach, so that’s what she focused on while juggling working from home, educating her oldest daughter, and entertaining a toddler simultaneously.

“I found I did really well when they would give us these fake dates for when we would go back to school,” McAllister explains. “Like, ‘I just have to make it to April 13.’ ‘OK, I just have to make it to May 1.’ The tipping point for me was when they took that off the table and said, ‘No, just kidding, you're not going back until the fall.’ I felt very powerless and overwhelmed.”

Before coronavirus, McAllister regularly attended two in-person meetings every week and would use going to the gym or planning a date night with her husband to relieve stress and prevent her anxiety from triggering her to drink. But with everything closed and Americans asked to stay at home, none of that was an option.

“I had this day where it was a bit of a spiral,” she says. “I just felt so much anxiety, depressed, sad, and a little defeated. It was crazy. My brain was looking for a way to not feel that. It wasn't like I was going to go to the store. But my brain went to that place.”

Instead of drinking, however, McAllister decided to share her coronavirus-related urges on social media. She explained that her increased anxiety and the over-saturation of pro-drinking COVID-19 memes that had flooded her feeds since California’s lockdown began had her thinking about relapsing for the first time in years.

A post shared by Emily | Chasing McAllisters (@emilymcallister_) on Apr 11, 2020 at 11:20pm PDT

“I'm not a person who cries in my Instagram stories,” says McAllister. “But I just let all the walls down and shared honestly about how I was feeling, and the response I got was crazy. There were so many people who were like, ‘Oh my God, I've been feeling that way and I didn't want to tell anybody because I didn't want them to think I was gonna get loaded.’ It was just really cool to hear. And sharing about it took a lot of the power out of it for me. Once I told on myself, [drinking] was not going to be an option.”

While quarantining, McAllister also decided to rev up her meeting attendance. Instead of going in person twice a week, she realized being stuck at home gave her more time to work on her sobriety. She started attending 1-2 virtual meetings every day.

“I'm telling you, I feel like I'm doing more for my sobriety than I had,” says McAllister. “It has lit a fire under me.”

“It Feels So Different This Time”

With no commute, more flexible schedules, and location being a non-issue, there are seemingly more paths to recovery available than ever before. Virtual meetings and telehealth treatment centers like Lionrock are a good thing for people looking to achieve and maintain sobriety—especially as the awareness of these options grows.

It’s not just that virtual offerings come with reduced barriers to entry, like being more affordable than traditional rehab. They also alleviate some of the stigma associated with addiction. Not only are participants exposed to a larger community of people who are seeking treatment, but for those who wish to maintain anonymity, signing on from home means you can attend meetings under a different name and even without showing your face.

Amanda Lynch had never sought treatment for her drinking before coronavirus hit. But for the last year, she’d known “something needed to change.” In January, she even tried giving up drinking cold turkey, but relapsed within a few weeks. She started reading books and listening to podcasts devoted to sobriety and wellness, searching for guidance, but always felt like something was missing. That’s when she started looking for virtual support.

“I've never gone to an AA meeting,” she says. “Everything I'd read about it just didn't feel like the right fit for me. The online avenues definitely work better for me.”

Were it not for COVID-19, Lynch suspects she might not have found so many great online support group options. Many were brought to her attention by sober influencer-types that she followed on Instagram, all rushing to share resources as everything moved online to accommodate stay-at-home orders. Lynch ultimately joined The Luckiest Club, a group run by Laura McKowen, author of We Are the Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life, which offers daily sobriety support meetings, coaching, and courses. She says finally being able to connect with others who are on a similar journey has changed everything.

“It feels so different this time,” says Lynch of her sobriety. “I’m not just saying ‘Oh, I don't want to drink.’ I don't drink. It’s deeper. I’m more excited about the possibilities now.”

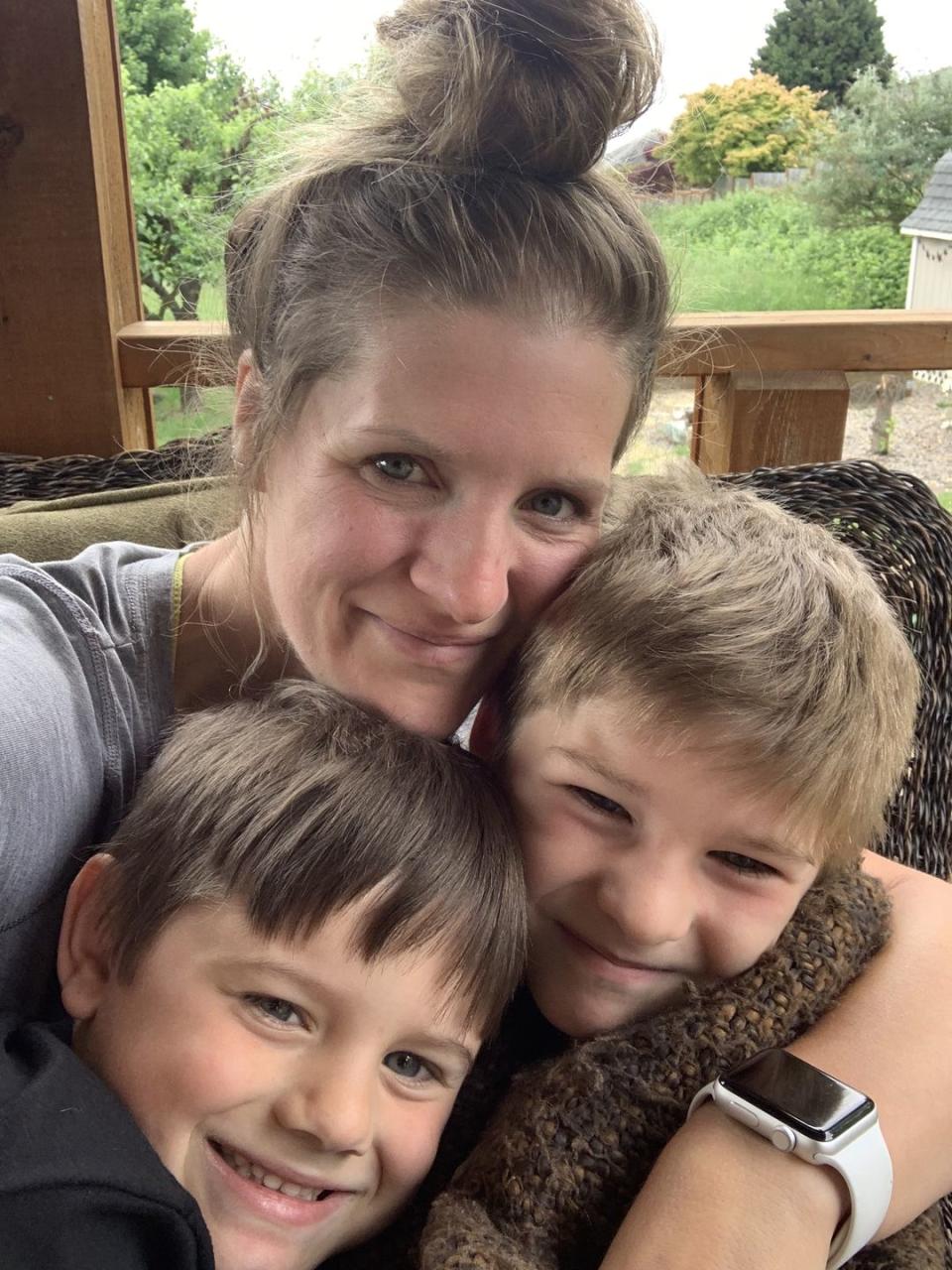

For those in recovery who were already sober, the surge of new virtual offerings was also deemed a good thing. Jessica Steitzer, an Oregon-based artist who runs the blog Sober in Wine Country, has always relied on virtual groups like Sober Sis that use apps like Zoom and Marco Polo to connect members with resources and facilitate sobriety- and recovery-centered conversations. But it wasn’t until the pandemic that she realized just how many options are out there.

“Coronavirus has opened my eyes to other networks like the Sober Mom Squad,” Steitzer says. “It helped me branch out and find other opportunities to connect with the sober community.”

“A Need Has Been Filled Up”

Emily Paulson, author of Highlight Real: Finding Honesty and Recovery Behind the Filtered Life, certified She Recovers coach, and one of the organizers behind Sober Mom Squad, is one of the recovery professionals who worked to make more treatment and support options available online this spring. In addition to the virtual group and individual coaching she offers year round, she also helped start a free online support group for women struggling with pandemic-related triggers. Roughly 600 women signed up, many of whom had never sought treatment.

“That's honestly been the best thing, [discovering] how many people really wanted to connect but were afraid to open the door to a room,” says Paulson. “This has been a really kind of non-confrontational way for people to seek help. I’ve talked to so many women—not only in our Sober Mom meetings and She Recovers, but lots of platforms that have launched meetings—who have said ‘I never started going to meetings until these virtual meetings were launched.’ So I do think that a need has been filled up that we didn't even know was there to begin with.”

I love my Sober Witch tank, @soberwitch ????????

A post shared by Emily Lynn Paulson (@highlightrealrecovery) on Mar 18, 2020 at 10:17am PDT

With all 50 states now in the process of reopening, Paulson does expect some people will be logging off after months of being stuck indoors in favor of attending in-person meetings. But for many others, she predicts the growing number of virtual support and treatment options will continue to be a saving grace.

“I think it's shown there was a segment of the population that wasn't getting served,” she says. “My hope is that when we do go back to normal, whatever normal is going to look like, there will still be a virtual component available for people.”

Support from readers like you helps us do our best work. Go here to subscribe to Prevention and get 12 FREE gifts. And sign up for our FREE newsletter here for daily health, nutrition, and fitness advice.

You Might Also Like