Cellphones offer look back at most personal moments of 2020

A year like no other: Americans shambled through it, doing the best they could under circumstances that were uneven at best — and sometimes downright punishing.

As they endured, here and there, they pulled out their phones and snapped photos of the world around them.

Snapshots of 2020. We all have them. And behind some are the stories of a pandemic and an era of polarization, progress and upheaval — the visual representations of daily life and its personal moments.

Associated Press reporters went back to some of the people they interviewed during the news events of the past year and asked a straightforward question: What image on your phone's camera roll tells YOUR story of 2020?

We are sharing some of their answers in photographs and words.

___

DEVON HENRY, VIRGINIA

Devon Henry’s Virginia construction company completed over 350 projects in 2020. But one, he said, was the most meaningful by far.

Team Henry Enterprises was the general contractor handling the recently completed Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia, a tribute to the people whose work building and maintaining the school founded by Thomas Jefferson had long gone unrecognized.

Henry is a Black man who faced death threats after it came to light that his company also handled this year’s removal of Richmond’s Confederate monuments. He took his kids, wife and mom to visit the Charlottesville site in November. He snapped this shot, which he said more than anything else, exemplifies 2020 for him.

“This was a year, for me, of reflection,” he says.

During the visit, Henry saw people taking their time exploring the memorial, reading through the entire timeline, touching the granite and feeling the names of the enslaved engraved into the stone.

The meaning of the monument and the way it has been recognized, he said, "personally means a great deal to me.”

— By Sarah Rankin

___

DEMETRIA HESTER, OREGON

Demetria Hester had been protesting racial injustice on the streets of Portland, Oregon, for 80 straight days after the killing of George Floyd when she was arrested. Hester’s hair had been falling out in chunks — from exposure to tear gas, she says — and her voice was cracked and hoarse from leading bullhorn chants for weeks.

The prosecutor in Portland decided not to press charges. But for Hester, the moment was transformative. She dyed her newly shaved head a golden yellow and shaved the Black Lives Matter fist into the back, tracing it with black dye.

Two weeks later, she traveled to Washington, D.C., to take part in a march to commemorate the 57th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream" speech.

When Hester saw the White House, she asked a stranger to take her photo from behind with her new hairdo front and center. Standing there, she said, she felt like she herself had become a “true civil rights entity.”

“So much led up to that moment,” says Hester, who ultimately protested more than 100 days in Portland last summer and fall.

“When I cut my hair, I was like, ‘This is for Black Lives Matter, this is about the power. You can’t take my brains. You can’t (take) my thoughts. You can’t take my ambition. You can’t take the strength my ancestors gave me,’” she says.

“This is part of a revolution,” Hester says. “It’s amazing to be a part of that, because we’re not going back.”

— By Gillian Flaccus

___

SARAH WEAVER, FLORIDA

Bandit Coffee in St. Petersburg, Florida, closed to customers on March 16, and state and local restrictions on restaurants soon followed. Owner Sarah Weaver quickly pivoted to contactless, curbside pickup orders — which was no small feat.

Pre-pandemic, Bandit didn't have a phone for taking orders and didn’t accept online orders for their carefully sourced, house-roasted coffee. Now, nine months later, most customers order online and pick up at a table under a tent — the staff places a name card next to the order, so the customers know which coffee to grab.

Although the state has lifted all restrictions on restaurants, Weaver says she’s “held steady” with the online system to keep her staff and customers as safe as possible.

“We’re fortunate for the temperate Florida weather,” she says. “2020 has been a time of change, but instead of forcing a return to normal, our team at Bandit has embraced how we can serve our community through creative adaptation.”

— By Tamara Lush

___

JUMANA AZAM, ILLINOIS

For a time this past spring, Jumana Azam was working 16-hour days responding to an influx of coronavirus patients at Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center. During the worst of it, the 34-year-old respiratory therapist was facing multiple deaths a day while close to 100 ventilators were in use on sick patients around her in the ICU.

“It was like war,” she says.

Her hours have decreased since then, but another major event in Azam’s life ended this year on a much brighter note: She got married.

Planning a wedding during a pandemic proved its own source of stress. The original plan was for the couple to marry in spring 2021. But with so much uncertainty and several aging family members, Azam and her fiancé decided not to wait.

After a small ceremony of 40 people, a friend captured a moment in the car while Azam and her new husband drove off, waving to tearful, masked family members.

“I cried throughout the whole ceremony, but in that moment, I was just so relieved that everything went well ... If you surround yourself with love and happiness, good things will still happen in a terrible year.”

— By Noreen Nasir

___

MARY DE LA ROSA, CALIFORNIA

Mary De La Rosa, a former early childhood educator, closed her toddler and preschool program in March due to the coronavirus pandemic. While the closing took a significant financial and personal toll, it also gave her more time to work with the Los Angeles-based racial justice group Westside Activists.

De La Rosa and her two daughters have attended protests and racial justice events every week since then. They make their own posters, write postcards to encourage voter turnout in swing states and call their elected officials. De Le Rosa uses her early childhood education background to help children, including her own, learn about racial justice.

“They’re the future,” De La Rosa says. “They need to continue to demand for change to happen if we want to make any progress. And I make sure they know that.”

Before a protest this past summer, 9-year-old Bella told her mother she wanted to be louder. Their solution: a paper megaphone with the words “Black Lives Matter.”

Bella spends much of her time memorizing protest chants. She has been chanting “Choose love, not hate,” around her family’s home for the past six months.

“I love to watch her chanting as loud as she can, using her voice,” De La Rosa says. “It’s been a year of her learning to use her voice and to use it proudly.”

— By Christine Fernando

___

RUQAYYAH BAILEY, MISSOURI

By any measure, Ruqayyah Bailey has had a tough year. But she is focused on her accomplishments, not her challenges.

Challenges are old hat for Bailey. The 31-year-old autistic St. Louis County resident was barely making enough as a part-time cafe cashier. When COVID-19 hit, the cafe closed. She lost her job and moved home with her mom.

The cafe reopened in the summer, and Bailey briefly returned to her apartment. It didn’t last. The social service agency that helps subsidize her housing had to shut down due to the virus, forcing Bailey to move back to her mom’s home again. To make matters worse, the cafe closed for good this month.

Through it all, Bailey relishes the bright spots. Her junior college classes are going great — two As and a B.

Then there is tennis.

In October, Bailey took first place in the beginners’ tennis division of the Missouri Special Olympics. A photo from her phone, taken by her coach, shows her standing proudly on the court, medal around her neck, a bright pink mask on her face.

“I did it! I did it! I worked hard and I did it!” she said when asked what the photo means to her.

Her can-do spirit came through in another way. As a child, Bailey was on a school bus involved in an accident and figured she’d never drive. Yet this year she took lessons and got her license last month.

“Thank God for that stimulus check,” she says, “because I used that for my driving lessons.”

— By Jim Salter

___

KANESSA ALEXANDER, MASSACHUSETTS

Like many who run small businesses, Boston salon owner Kanessa Alexander found the pandemic to be a rocky time.

The Black mother of four opened her shop about five years ago in the city’s predominantly white West Roxbury neighborhood after she was denied service herself in high-end salons. Now she’s seen her staff dwindle from eight to one, leaving her and one stylist to handle clients at less than 30 percent capacity due to pandemic safety rules and far fewer customers.

A selfie she took July 20 wearing a mask at her four-chair salon, Perfect 10, tells the story, the 43-year-old Alexander says.

“I was in the salon alone with a mask on when we were closed. It was such an uncertain and uncomfortable time,” she says. “It was a summer day, and it should have been a day that I was at the beach with my kids or in the salon with a full staff working. It felt very different. I could see it in my eyes. I could see it in everyone’s eyes.

“We were still trying to figure out, where do we go from here? The Black Lives Matter movement was happening, and there were protests. It was, should we board things up? It was a whole series of events in the midst of summer, which should have been a joy.”

— By Leanne Italie

___

PONNI ARUNKUMAR, ILLINOIS

Regular forest walks have helped Dr. Ponni Arunkumar get through one of the most challenging years of her professional career.

The medical examiner for Cook County, which includes Chicago, scrambled early this year to cope not just with a spike in COVID-19 but also with soaring numbers of homicides. Deaths tripled overall from the year before. But the size of Arunkumar’s staff remained the same.

She says her photographs of one of the forest-preserve trails she walks each weekend with her husband are reminders that downtime isn’t a luxury — it’s a necessity for staying sharp amid the county’s death surge.

“It has been a very long year ... and we don’t know when this is going to end,” she said.

She made her weekend walk part of her routine over the summer as COVID deaths waned. They are now up again, and she intends keep doing the weekend walks.

“This prolonged stress can get to you,” she says. “Not just me but the whole staff. … It has started affecting us a bit.” She adds: “Everyone needs a break.”

— By Michael Tarm

___

MEYERS LEONARD, FLORIDA

Meyers Leonard of the Miami Heat wanted to pick a family photo as his favorite of 2020, one featuring his wife and dog and some more relatives.

Instead, he chose one of himself, alone, surrounded by darkness.

“I’ll say, as a blanket statement, 2020 was not easy for anyone,” Leonard says.

His image, however, also shows strength and some light. It was taken by a Heat employee after an extra workout Leonard had in the NBA’s restart bubble at Walt Disney World in Florida over the summer.

Leonard felt alone there. He lost his starting job in part because of injury. His wife wasn’t allowed to join him until the end, and he was sharply criticized for his decision to stand for “The Star-Spangled Banner” before games while most players chose to kneel.

“I have no shame saying that parts of 2020 were very, very difficult for me,” Leonard said. “And I’m willing to speak up and say that it’s OK to not be OK. There are too many people, especially during COVID, going through things. Friends of mine haven’t seen their parents in almost a year. I mean, it’s crazy. I thought I had everything, and sometimes life just gets flipped upside down.

“Yet people need to know, there is a light. There is a light at the end of the tunnel. Trust me, I’ve had moments where I’m in the dark you see in that photo. But there is a light, and there is hope, if we stay strong.”

— By Tim Reynolds

___

DALE TODD, IOWA

The Aug. 10 derecho that hammered Cedar Rapids, Iowa, with winds up to 140 mph severely damaged tens of thousands of homes and businesses and devastated the community's tree canopy.

Much of the city of 130,000 people was without electricity for a week or longer. “It feels like we got kicked in the teeth pretty good,” city councilor Dale Todd says.

But Todd says the lack of power and air conditioning caused something “sort of magical” to happen: Once-distant neighbors came together to help as the city started a massive effort to clear debris.

Todd’s family and neighbors gathered every night for community meals, at first featuring meats that had to be used or would spoil. They talked about their days and looked at the stars from Todd’s backyard without distractions from cellphones or television.

In this photo, Todd’s wife, Sara, fixes the mask of their 21-year-old son, Adam, who has severe epilepsy. Todd calls the photo a reminder of the “powerful sense of community that evolved.”

“That is what is going to get us through this pandemic, through this next year with the economy," he says, “and hopefully it can be a model for how we rebuild our politics and sense of democracy.”

— By Ryan Foley

___

RUTH CABALLERO, NEW YORK

When home health nurse Ruth Caballero looks at an April photo of her wearing her full kit of pandemic protective gear, she sees a feeling: “how scared I was.”

Covered in a surgical gown, face shield, plastic cap and two layers of masks and gloves, she was heading into a New York City apartment to see one of her first coronavirus patients, just released from a hospital.

“I remember putting all of that on and saying to myself, ‘Please, let me be able to be as effective medically to help this patient as much as I can. And please allow me to stay COVID-negative,’” recalls Caballero, who works for the Visiting Nurse Service of New York.

Moments later, Caballero came face-to-face with the ravages of COVID-19, meeting a tremendously weakened patient who asked: “Nurse, did they send me home to die?”

“No, they sent you home to live,” Caballero remembers saying. “And we’re going to fight this together.”

Caballero’s cellphone photo is a portrait, one of many, of New York City’s fearsome battle with the coronavirus. During an early April peak, it was blamed for over 750 deaths a day in the city alone. Still, Caballero glimpses more than those desperate times when she looks at that picture.

She also thinks of how different she felt two or three months later, as that first surge subsided, protective equipment shortages eased and she gained experience caring for coronavirus patients — and seeing them get better.

By then, “I looked forward to being able to provide them with nursing care,” says Caballero, who now has worked with more than 50 COVID-19 patients. “I’m not afraid,” she says. “Whatever I can do to help them recover, it is one of my greatest joys.”

— By Jennifer Peltz

___

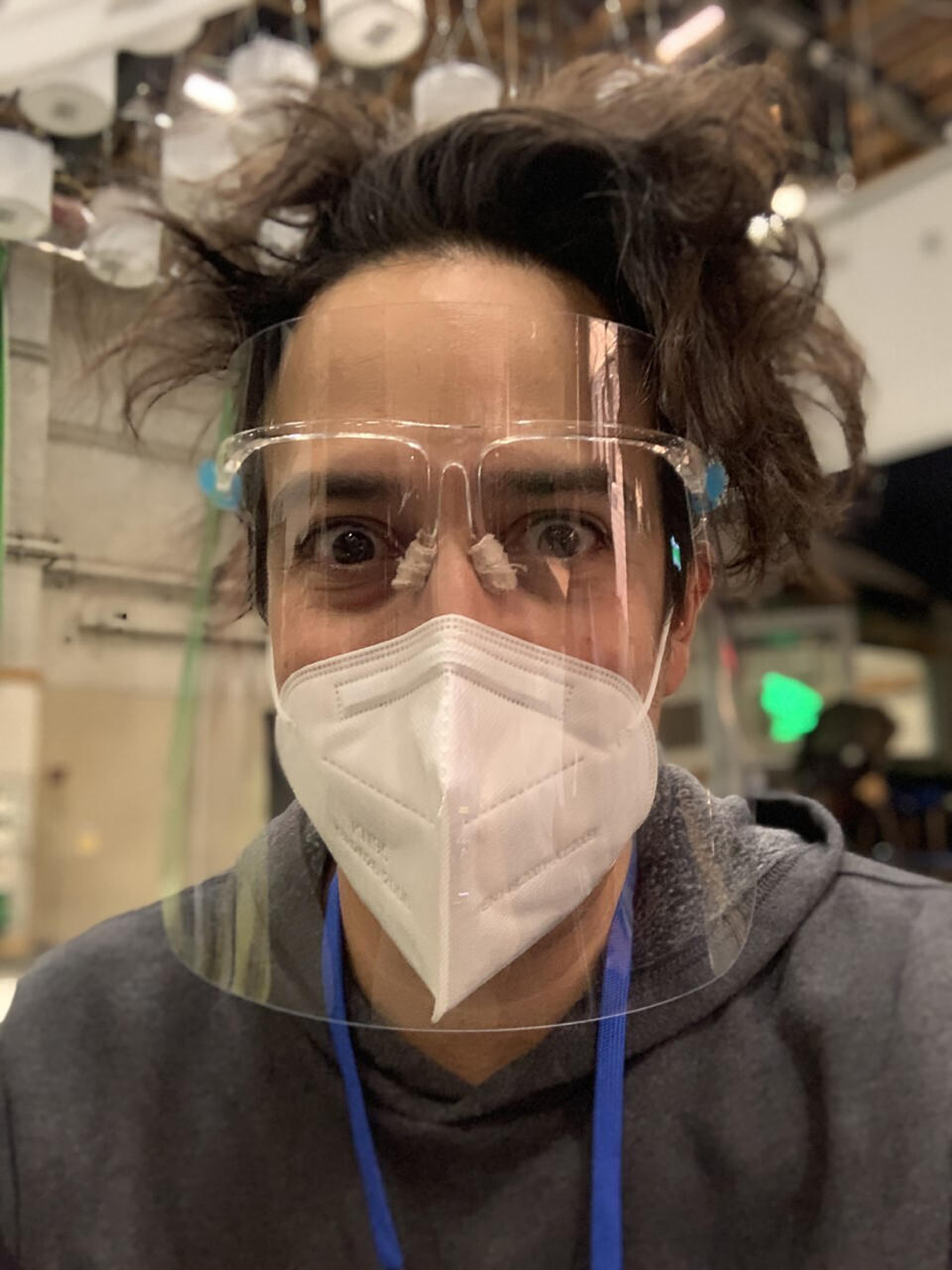

LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA, NEW YORK

Lin-Manuel Miranda already wears plenty of hats: He’s a Broadway playwright and producer, singer, songwriter, actor, rapper and composer.

But at the beginning of 2020, he was set to add a new title to his resume: film director. Until the coronavirus pandemic changed his plans, that is. Netflix had to shut down production of his directorial debut, the musical drama “Tick, Tick... Boom!,” earlier this year after only eight days of shooting.

“We started back up again in September. We wrapped just before Thanksgiving. And I’m incredibly grateful and proud to say that we were able to finish filming with no one getting sick, no delays,” Miranda says.

With wild hair and eyes wide open, the entertainer — in a face mask and face shield — took a selfie on the New York set of the film, which stars Andrew Garfield and Vanessa Hudgens. It will be released next year.

“The picture you’re seeing is me at the end of the day of our most complicated musical sequence. ... So that’s why my hair is literally standing straight out of pure exhaustion,” he says.

“We really kind of learned a new way of filmmaking,” says Miranda, who this year released the 2016 filmed version of his Broadway musical “Hamilton” on Disney+ as well as “We Are Freestyle Love Supreme,” the Hulu documentary highlighting his improv skills. “It was a lot on top of what is already a hard gig, but it also made finishing it all the sweeter.”

— By Mesfin Fekadu, AP music writer

___

ADAM RAMMEL, OHIO

Adam Rammel enjoyed seeing a full house at his brewpub, Brewfontaine, and had high hopes for his second location next door, the Syndicate. But for three months, from March 15 to June 5, the Bellefontaine, Ohio, restaurants were closed to indoor diners and limited to takeout and delivery. Rammel can't shake the image of upside-down chairs on tables in an empty dining room.

Social distancing and customer anxiety have reduced the restaurants’ Friday and Saturday night crowds from an expected 130 people to 60 at best. With winter here, Rammel and his co-owners have given up on serving customers outdoors. Like other restaurateurs, he hopes the widespread availability of a coronavirus vaccine will bring back the crowds.

Asked how he’s been able to get through more than nine months of anxiety, Rammel said he’s been helped by “an amazing support system with partners, including my family. Trying to remain positive. And bourbon. Lots of bourbon.”

— By Joyce Rosenberg, AP business writer