Bret, Unbroken

You know what people think. They see jeans too short and winter coat too shiny, too grimy, and think, homeless. They watch a credit card emerge from those jeans and think, grifter. They behold a frozen grin, hear a string of strangled, tortured pauses, and think, slow. Stupid.

You learned too young about cruelty and pity. You learned too young that explaining yourself didn’t help, that it made things worse. People laughed. Made remarks. Backed away. So you stopped explaining. You got a job, got a cat, got an apartment, and people can think what they want to think. You built a life without explanation and it was enough.

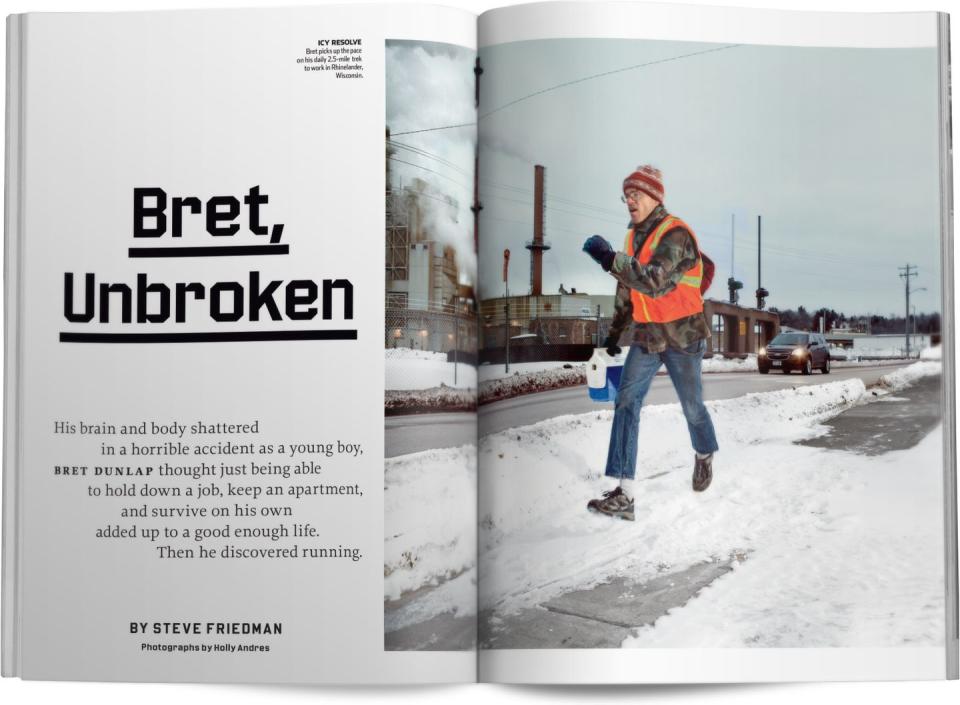

What people see now, this moment, is a solitary man leaning into the wind, trudging down snow-dusted streets toward a faint, watery dawn.

It’s December 20, 2012, almost the shortest day of the year. You have been up since 4:30 a.m. You have eaten your oatmeal and cranberries, and you have fed Taffy the cat and packed your lunch of canned chicken and coleslaw, and you are alone on the streets of Rhinelander, Wisconsin, an industrial town of 7,800 that squats at the confluence of the Wisconsin and Pelican rivers, deep in the woods of the Northern Highlands. It’s 2.5 miles, at least part of which you usually run, to Drs. Foster and Smith, the mail-order and online pet-supply colossus where you have worked for almost 18 years. (Warehouse dummy, people think, and they don’t know about your college credits or your study of military history or that you speak German, understand a little Russian, and can say “How are you?” and “Thank you, goodbye,” in Romanian.)

When you crest a hill half a mile from the warehouse, you pause, turn, and notice the quality of the light, how even in the hard, cold days before Christmas, the weak morning sun turns the smokestacks and factories of downtown Rhinelander into friendly things, peaceful and benign. You think about the most beautiful light in the world, the sunrise behind the barn due east of your mother’s house, 65 miles away. No one knows what you think about the quality of light. Few know that you love horses, or that you have plans to breed chickens, or that you long for love, or that you have hardened yourself to never receiving it.

That’s fine by you. It used to be fine, in any case. It was fine before the day two years ago, when your brother Eric asked you to run a 5K race. He was running a 10K, and he thought it would be nice to have company. You refused—you didn’t want to make anyone uncomfortable. You didn’t want to deal with people looking at you, with them thinking things.

But he was insistent. That was the day you started running. Since then, you haven’t been so sure about things. You’re 45 now, and you’re not so sure you know what people think. You’re not so sure about the life you have spent so much energy constructing.

You’re not so sure it’s enough.

You don’t remember anything from before the accident, and you know that’s a blessing, a small one in a life filled with blessings that are too small for most to see. You don’t remember the chicken coop behind your house, or how Eric played the saxophone, or how the family’s black Labrador, Snowball, howled along.

You were 6, a kindergartner, and it was October, and you were running across the street in Mukwonago, Wisconsin, on the outskirts of Milwaukee, to see your best friend’s new toy truck. His grandmother had been visiting from North Dakota and he was hollering for you to come see it, so you broke from your older brothers, Eric and Mark, and darted into the street. Approaching from behind a curve at the bottom of a hill, the driver of a pickup truck happened into the worst moment of his life. On one side, a little boy and his grandmother and his toy truck and five other children, all waiting for the school bus. On the other side, your brothers. All of them gaping at you, in the middle of the road.

You were wearing a hooded nylon Packers jacket and a piece of the pickup truck’s grillwork stuck to it. Your shoes came off—still tied, with the socks still in them—as your body skidded down the road. It skidded 50 or 60 feet before a man in a VW Beetle jumped out and stopped you. There wasn’t a visible mark on you.

The driver who hit you slammed on his pickup’s brakes, jumped out and ran to the nearest house, pounded on the door. The woman who answered said, “Calm down. It’s one of Barb’s. She’ll have already called an ambulance.” And she had. Your mother had seen everything.

The ambulance took you, unconscious, to Waukesha Memorial Hospital. Your pelvis had cracked in two places, and your large intestine was torn open. Doctors removed your teeth, which had been broken and loosened by the impact. They performed a colostomy, put a brace on your left leg and a cast on your right one, which they put in traction. Your mother arrived with your kindergarten class photo, taken a few weeks earlier. She shoved it at one of the doctors. “This is what you got,” she said. “I don’t care what you do, just get him back to me alive.”

With the cast and brace and all the bandages, the only part of you anyone could see was one foot, so your mother stroked that foot. She called her mother, who lived next door, and told her to take care of your brothers, to get them to school, to make everything as normal as possible, and when doctors told her you had suffered a terrible blow to your head, that your brain was severely damaged, that you would never walk or talk again, that your intellect would never progress beyond that of an 8-year-old, that you would die by the time you were 13, she said nothing, kept petting your foot.

Nothing happened for days—or a week, or two weeks, no one remembers—and when your grandfather was visiting, doctors told him they’d have to perform an operation to relieve the swelling in your brain, and the procedure was risky, it might kill you, but that if they did nothing, you would certainly die. They told him that everyone should prepare for your death, and he asked the doctors if they had told your mother, and when they said they had, he told them he was sure your mother was taking care of everything, and he was right. Your mother had called the funeral parlor.

She brought in a tape recorder and the tape she had made. The chickens and Snowball. Eric wailing on his saxophone. She strung ornaments from the wires above your hospital bed. You were still unconscious, but she talked to you. She brought in the teenagers from the YMCA who had taught you and your brothers music and judo and swimming. Eric and Mark kept going to school and every day their teachers asked, “Has he talked yet?” and every day they had to say no.

You needed blood, more than your mother and her family could provide. She told a neighbor and the neighbor said not to worry, her dad was a foreman at the Waukesha Motor Company, he could do something. He told all the shifts, “Okay, there’s a little guy in the hospital, and he needs blood, and need I remind you, all your vacation vouchers go through me?”

You awoke from the coma, but you didn’t speak, and then one day you did. You don’t remember what you said, but your mother does. You said, “No!”

The doctors told your mother you should be moved to a rehab facility, where you could live out your days. If living was the right word.

Your mother was a hard woman, who by her own admission liked horses better than dogs, and dogs better than most people. She was poor—your mother didn’t believe in euphemisms—working for her brother, who owned a greenhouse. Your father had been gone for a while. (“Oh, he was a loving man,” says your mother. “He loved tall and short. He loved blond and brunette and redhead.”) Your mother was under no illusions about the comforts you’d receive at home. But she grabbed a nurse and together they wrestled you onto an air mattress and they shoved the air mattress into the back of your mother’s green Pinto station wagon, and for what doctors thought would be a few miserable years, you went home.

She wouldn’t let you have a wheelchair. Your mother was a hard woman, and she knew she would die one day, and if by some miracle—some great, undeserved blessing—it happened before you were gone, she knew you would have to be hard, too. She wrestled you onto that air mattress six days a week for months, slid you into that Pinto, and drove you to the physical therapist and the occupational therapist and the speech therapist.

It was the left side of your brain that had been injured. (Hemiparesis was the technical diagnosis.) Because of that, you had trouble with balance, and weakness and nerve damage in the right side of your body—right-handed before the accident, you would have to become a lefty. The left side of your face was partially paralyzed. Your speech was impaired. You needed medication to prevent seizures, medication you would take for years. To the doctors’ surprise, your brain started growing again, but it didn’t work like it used to.

So you learned to read, then you forgot. You learned arithmetic, then forgot. You learned to talk, then forgot. You had to learn things over and over again.

Your mother loved musicals, and trying to sing along with her was sometimes easier than trying to talk. She and your grandmother also read you stories from baby books, showed you how to add two plus two. Even today, your mother can quote pages from If I Ran the Circus. If asked, she said you had problems. She refused to use the word “handicapped.”

Whenever visitors came over, they brought you toys, and your brothers were delighted, because they’re the ones who got to play with the toys. G.I. Joes were the best of all. Eric, 10, was unfailingly kind, solicitous. He had always been that way. Serious, quiet, he had announced when he was 5 that he wanted to be an ichthyologist, and asked for a bathyscaphe for Christmas. He would go on to become a high school physics teacher, before making the suggestion that would change your life. Mark, 8, wasn’t unfailingly anything. Wild, unpredictable, impulsive, he would spend his teenage years running a high school loan-shark operation, employing teenage muscle to keep the enterprise efficient, joining the Army right out of high school, then, after that, becoming a long-haul trucker. Mark teased you, commandeered your G.I. Joes. But woe to any other child who picked on you—and there were a few, before Mark and his gang got hold of them.

A blizzard came that first winter home, cutting power, closing the roads. Eric nailed blankets over the windows, spread blankets over the living room floor. One of your mother’s girlfriends had a husband with a snowmobile, and he brought you your anti-seizure pills.

Your mother was poor, but she knew that education was important, and she knew what a comfort music could be, and she made your brothers take piano lessons, so she made you take them, too. Your right hand didn’t work? Big deal, her brother had a boy with Down’s syndrome, and when he was over, your mother gave him a saw and told him to go outside and get some wood for the fireplace.

If your cousin with Down’s syndrome could saw wood, you could learn to play the piano. Your mother explained the situation to your brothers’ music teacher, told her what she wanted. What she needed. And your brothers’ music teacher found a composer—a veteran of the Crimean War who’d had his right hand blown off. He had composed music for the left hand only. You learned how to play the piano left-handed.

You would grow into a man who built a life alone, a safe strategy that could keep out teachers who thought you were slow, doctors who called you stupid, children who teased you. You remember most of them. But you don’t remember everyone.

At Clarendon Avenue Elementary School, there was a foot race, and you had trouble walking, never mind running, but all the kids had to compete. One of the fastest kids in your class was also one of the most rotten. A mean lowlife destined for a bad end. That’s what your mom remembers hearing about him. But she also remembers him finishing the race, and then looking back, and seeing how far you had to go, and jumping back on the course, and finishing the race again, right behind you, not making fun of you, but keeping you company.

There were the pills and the one-handed music lessons and everything else, but your mother had refused to sue the man who had hit you. He hadn’t been drinking. It was an accident. He had kids, too. That’s the way she saw it. She had fired her lawyer because he had decided to research the assets of that man. She had yelled at that lawyer, too. How dare he?! And she had yelled at the judge, the judge who told her to sit down and shut up, and who told her lawyer she should sue or be reprimanded for being financially irresponsible. “That man didn’t get up that morning and decide, ‘I’m going to wipe out a 6-year-old!’” she yelled at the judge.

Your mother got by. Your uncle paid her every week you were in the hospital, but not long after you got out, she returned to the greenhouse, and she got into a squabble with your uncle’s wife, so she took other jobs—waitressing, wrapping meat at one deli, taking orders at another.

If you were pouring milk into your cereal bowl and you spilled it all over, your mother grabbed a towel and cleaned it up, but she left it to you to make yourself another bowl. You fell down a lot and when that happened, she wouldn’t even stop talking, she’d just reach down and put you on your feet and if you fell again, she would pick you up again.

Your broken bones healed. Doctors reversed the colostomy. Because of the brain damage, you still walked awkwardly, but you fell less. You talked more. And to others, it might have looked like a happy fable: Little boy suffers grievous injury, through tough love and support finds his place in the world. But you hadn’t found your place.

If your mother didn’t know it then, she would soon enough. You were in second grade. It was a spring afternoon, and your mother had come to the school. She might have been hard, but she could also be fun. Every so often she’d stop by school and gather you and your brothers, and maybe a few other kids, and take all of you to go feed the ducks, or to go fishing, or to just sit by a lake and play.

She was on her way to your classroom when she saw you in the hall. You were throwing books and ripping paper. You had reasons, you knew that, and she did, too. The right side of your body didn’t work well. Neither did your mouth. You knew answers and couldn’t say them fast enough and you knew that people thought you were stupid, and you weren’t. Your mother knew how frustrated you were, and if she had been someone else, she might have held you, stroked your head, comforted you.

She snatched you up and she paddled you, right in the school hallway, and people were watching by now, they had heard the commotion and they were shocked, but they didn’t know what she knew, they didn’t know what she told you that day, dragging you out to her car.

“You can’t do all the things the other kids do?” she said. “Tough. You are going to have to deal with it.” She was not religious—she had her reasons, generations old and having nothing to do with you—but now, to her sobbing, raging second-grader, she invoked God.

“God never said anything about fair,” she said. “He said you got a chance.”

After that, she grabbed a marker at home and she scrawled this onto your school bag: “Failure is not falling down. Failure is not getting back up.” She wrote the same thing on the refrigerator.

She read to you every day. She did math problems with you. She paid you and Mark a penny each for every fly you killed. She let you play horseshoes, and didn’t let you see how that terrified her, and everyone else in the vicinity. And she might have softened, might have let you slide when things were toughest, might have given you a break. But she didn’t.

The doctors had told her to make sure your clothes had Velcro fasteners, so that you’d be able to get in and out of them yourself. But she knew the easy cruelty of children, knew the taunts you would easily incite without pasting Velcro targets all over yourself. So she made you shirts with giant buttonholes, and she bought big buttons and she sewed those on and she told you that you were going to learn how to button your clothes.

That first night she and her mother—your grandmother—stood in your room and watched you. When you got to the last button you—and they—realized you had miscalculated, that the two sides were misaligned by one buttonhole. Your grandmother moved to help you. “Get back! If you can’t keep your hands off, you should go home,” your mother snapped. “He needs to learn to do it himself.”

And as you unbuttoned your shirt, with your good left hand and your claw of a right hand, your grandmother stood with her own hands clenched behind her back, to keep them from reaching out to you, and she wept.

Your mother watched, dry-eyed.

Your mother took you to a support group for people who had suffered brain injuries, and their families. When one of the mothers of another young man, also brain-damaged, said, “I’m a survivor, too,” your mother snapped, “Oh, no, you’re not. You’re a parent. This is your job!”

You were put in special classes in high school, and hated them. Other kids would frown and whimper if they couldn’t answer a question and then an advisor would do the work for them. You didn’t want anyone doing your work. You studied Latin because rolling those strange words around your tongue seemed to strengthen it, and German because thinking sentences through in that language helped you express them in English.

By the time you were a sophomore in high school, Eric had left for college and Mark’s loan-sharking business was booming, and his friends—Speedy and Ben and Rich—were your friends. One of them was gay, and your mom was worried that he was a bad influence on you. Not because he was gay. Because he was sneaky. If you were gay, that was fine, but she wanted you to be gay because you were gay, not because you were lonely and one of your loan-sharking brother’s sneaky friends was a predator.

When you were a senior, six weeks before you were due to graduate, your mother got a call from your school. You had walked out of a class and nobody knew where you were. She found you on State Highway 83, headed north. She asked where you were going and you said you didn’t know. But you were going. You refused to return to Mukwonago High School that day, or ever again.

What was the point? You knew you’d never be able to speak well, you’d never be able to tell people everything you were feeling, everything you were thinking. And what you were feeling and thinking was a mess. You were taking Depakene and Peganone to prevent seizures. Your right hand didn’t work properly, and sometimes, especially when you got tired, you limped and listed and there were long silences between your words. You knew you’d always put people ill at ease. What kind of life was that?

You knew what other people thought. You knew what life would be like. You knew what to do. You took a fitful shot at killing yourself. You don’t like thinking about it. You don’t like talking about it.

Your mother took you to the hospital, where a psychologist told her you were a “dullard.” Your mother had found a one-armed composer. She had managed to wrestle you and that goddamn air mattress into her goddamn Pinto. She had found you the blood you needed, and taught you to speak again, and willed you to button your own shirt. So of course she could find a doctor who would take the time to listen to you. To see you. To know you. And she did. He worked in Milwaukee, and he was kind and he listened. And understood. He understood that life was hard, and that life for someone with brain injuries was nearly intolerable, and that all the medications you were on took the “nearly” out of it. He knew how you felt.

“Bret’s smart,” he told your mother, as if she didn’t know that. “By the time you get done talking to him, you’re almost convinced suicide is a logical option.”

It took time to cure those thoughts. Once, your mother found you in your bedroom with a machete. “You want to kill yourself?” she screamed, seizing the machete. “Here, I’ll help you!” She smacked your legs with the handle.

Eventually the doctor suggested taking you off all the medications. He told your mother she might lose you, but it was a gamble worth taking. She and you agreed.

You kept seeing the doctor. You passed your high school equivalency exam. You prepared for the rest of your life.

You decided to take the civil service test for a post office job. You asked that you be able to fill out your name and address before the test started, so you wouldn’t waste so much time writing. They refused. They thought you were trying to gain an unfair advantage. It wasn’t the first time people had misjudged you, and it wouldn’t be the last.

You told your mother you were going to take a data entry course at Waukesha County Technical Institute, and she said sure, if that’s what you want to do. You said you’d get there yourself, and she said of course, if that’s what you wanted.

You walked to West Greenfield Avenue and got on the number nine bus, and you didn’t know it, but behind the bus, slid down in her seat to make sure she wasn’t seen, was your mother. She had never felt so proud. She had never—except for days in the hospital—felt so frightened.

You, Mark, and your mom moved north to Pine Lake in 1987 when she bought a bar—The Whispering Pines—and those were good years. Your mother met a man, Oscar, 15 years younger than her, and kind. You tended bar and got to know people, and people got to know you. Your mom and Oscar married; they lived upstairs and you and Mark lived in an apartment below. You took classes at Nicolet Area Technical College. You got A’s in Computer Concepts, the Psychology of Human Relationships, Economics, and Creative Writing. Business Law and Intermediate Algebra, you got B’s. Fundamentals of Speech, you got a C.

You wanted to be more than a bartender. You applied for jobs around town, but the people hiring said you should be able to type. Of course, you could type. But you couldn’t do it fast enough. You filled out an application at a local gas station—it was long, and it took quite some time and you didn’t like the way the person at the desk watched you labor over it—and after she thanked you, and you left, your mother saw her tear up your application and throw the pieces in the trash can.

One place that was interested in you was Drs. Foster and Smith, a pet-supply business. But the supervisor was curious. You were receiving disability insurance. Did you not know that working a steady job would jeopardize your monthly government check? Why would you want to do that? You explained to the person that you wanted to work because that’s what men did. They worked. Did she have a problem with that? She did not, and she said the company would be glad to have you, and you decided that you thought you might fit in at Drs. Foster and Smith.

You started work on August 29, 1995. You were employee number 860. You worked near another young man named Marko Modic. You lifted things and you moved heavy things and it didn’t take Marko long to figure out—once he got past your difficulty with language and the way, late in the day, the right side of your body stiffened, and the left side of your face froze up—that you were a smart guy. Really smart. And funny. Smarter and funnier than most everyone else in the warehouse. You and Marko would talk about politics and women and sports, and you would join the other warehouse employees one day a week to play volleyball. It didn’t take you long to realize that with your balance issues and the way the right side of your body didn’t work so well, you couldn’t play. You stayed on the sides, making wisecracks.

Marko realized that for all your jokes, you had a chip on your shoulder. You acted like you had something to prove. When someone else would carry a five-gallon bottle of water up a flight of stairs, you would carry two jugs, one on each shoulder, right-side weakness be damned. If someone would ask about your injuries, you’d shut them down. We’re all different, you would say. End of story.

Marko got to know you, but not many others did. The company hosted an annual summer picnic and an employee appreciation Christmas luncheon, but you didn’t attend. Dealing with others was exhausting. And you knew that you made them uncomfortable. You knew what they were thinking when they saw you. Lunchtime, while others were knotted at tables in the cafeteria, talking about whatever people talked about, you sat in the break room, in front of the television, wolfing down your chicken and coleslaw.

People offered you rides to work, but you knew they felt beholden, and you didn’t want that, so you refused. You didn’t want to risk making anyone more uncomfortable. You walked to work and you walked home. You walked to the grocery store and the Laundromat and you walked to the Red Cross blood center because you wanted to be useful. You watched a few TV shows and went to bed early, and you got up and you fed Taffy and had your oatmeal and cranberries and started over again, and it was enough.

Your mother had been a hard woman, and she had done her best and she had succeeded. You were a hard man.

If only you could have explained to people all you knew—about farming and animals and your cat and the designer chickens you planned to breed, about military history, and how you knew Latin and German, how you longed for a woman’s touch…. But you couldn’t explain it to them. That was part of the problem. That was the problem. They didn’t want to hear you try to explain, because you made them so uncomfortable. You knew that. You knew that even if you found the cure for cancer, unless you could speak it or write it, it was useless knowledge.

You didn’t want to be useless. You helped your mom and Oscar around the house. You memorized four-digit bar codes for items in the warehouse so that when someone needed something, you knew exactly where it was. You toted those gigantic jugs of water. You didn’t take vacation days (partly because the paperwork required for a vacation was so daunting). When you weren’t working hard, you studied. You took Introduction to Sociology and American History to 1865 and American History from 1865 and Marketing Principles and Personnel Management. You started a retirement account. The Red Cross only visited Rhinelander to collect blood four times a year, so you started visiting the Community Blood Center at Trig’s Food and Drug in the RiverWalk Center, on South Courtney Street. They would take your blood every two months, unless your iron was low. If that happened, you made sure to eat more spinach and fish and Total cereal. People built their lives differently, and you had built yours. It was lonely, but you could manage. It was enough.

In 2003, when you were 35, your mother and Oscar told you they had bought a farm 65 miles west, and they would be moving. Would you like to join them? There would be horses and chickens.

You declined. You had been working at Drs. Foster and Smith for almost eight years. Did Oscar and your mother seriously think you would consider giving up your seniority?

Your mother was so proud, yet again. And so afraid.

You stayed in Pine Lake near your brother Mark until the bar sold in 2007. Then you moved to your apartment in Rhinelander. It was the first time you would be living completely alone. You still avoided the Christmas party and the company picnic. You still turned down offers of rides to and from work. You had a job, and three Fridays a month your mother and Oscar picked you up after work and you had those weekends at the farm, and it was enough.

Then in early spring of 2010, Eric phoned from Houston, where he was teaching high school science, and he suggested you join him in a 5K run in Rhinelander. You declined. Not because you didn’t think you could do it. You had been walking five miles a day, to and from work, for years, so how difficult could running be? But you knew how uncomfortable you would make the other people, the people who could speak in paragraphs, the people whose right hands didn’t tire late in the day, whose smiles didn’t freeze. And you worried about your balance. What if you stumbled in the middle of the race? What if you fell over? Eric persisted. “C’mon,” he said, “it’s a group thing, but you’re alone. You’re not going to bother anybody and nobody’s going to bother you.” Did you enter because Eric wouldn’t let up, or because of something else? You’re not sure.

You made it through the 5K in tennis shoes from Walmart with the soles coming loose, and that was one of the first times you realized that what you thought you knew wasn’t always true. Running miles wasn’t the same as walking—your legs felt like rubber bands. And no one seemed uncomfortable around you. People seemed preoccupied with how they were going to do. They said hello, and you said hello, and they smiled and you smiled. Maybe you weren’t helping others, but it felt good. The race finished a couple blocks from your apartment, so you and Eric jogged over there and showered before going to the awards ceremony. People welcomed you, asked you your time (29 minutes), smiled and chatted, and it didn’t really matter how slow you talked, how often you had to pause for answers. No one seemed to care. Your boss’s wife was there. So were other people you knew. Five weeks later, you ran another 5K in Park Falls, Wisconsin. The night before, you woke with a cold, but you ran 29 minutes again.

You bought a new pair of shoes, the kind with the big N on them. You decided you had to strengthen the right side of your body. To do that, you needed to go to the gym. You took some of the money you had been saving and you applied for a membership at a local health club, and when you pulled out your credit card and asked if the club accepted it, the guy behind the desk—a big, muscle-bound guy—looked you up and down, at your short jeans and your old jacket and at the smile frozen on your face, and he said, “Well, sure, if it’s your card,” and you turned and left. But you didn’t quit. Failure isn’t getting knocked down. You joined Anytime Fitness, in downtown Rhinelander, and your first time there—after your 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. shift at the warehouse—the manager showed you around and explained the machines and you nodded, and you got on one of the treadmills. There was a woman on the treadmill next to you, an older woman, and she smiled and saw you were new because you were struggling to set the programs on the machine. She asked how fast you wanted to go. You knew you made people uncomfortable, but she was so nice and you didn’t want to be rude, so you answered, thinking she had asked how far you intended to go. Four. You were going to go four miles. She smiled and nodded, but the truth is, she could see not just that you were new but that you were different, and she thought four miles an hour seemed a little fast. But she kept quiet when she helped you punch the buttons.

You nearly flew off the machine and the woman nearly screamed. You recovered on your own, though, and she helped you adjust the machine to a lower speed and you made it those four miles, and that woman thought about how she had never seen a stronger, more determined person in her life.

You kept at it. Your weak right side meant extra effort, extra focus, to keep from falling as you ran, but you kept at it. You had learned to button your shirt with your claw of a right hand. You had learned to play piano left-handed. Of course you were going to become a marathoner. You had heard about the Disney World Marathon and had always wanted to visit Florida, but you checked, and it was filled up. So you found one closer, the Journeys Marathon in Eagle River, and enrolled for the May 2011 event. But before it, you flew to Las Vegas and ran the Thin Mint Sprint, a 5K, at the end of January 2011. By yourself.

The day before the race, at your motel, there was a poker tournament. “Look at the dummy, look at the retard,” is what you told your mother the other players were thinking. You won $60.

You ran the race, you returned to the gym, and you asked your mother if she would keep May 14 open. You wanted her to come to Eagle River to watch you run in the Journeys Marathon. You hadn’t even run a 10K. You couldn’t even walk from her house in Kennan to the barn without swerving. How the hell were you going to make it 26.2 miles? The hard woman told you that you were nuts and told you that you didn’t want to do this, that you should run a half marathon first.

But she and Oscar drove three hours to the race. You wore a cotton T-shirt and over that, a green cotton Whispering Pines sweatshirt that you wore when you did chores at your mother’s barn. You wore nylon running pants over your shorts. You were freezing and your mother thought you might die. She knew the cutoff was six hours, and she seriously doubted you would make it and wondered how you would take this setback. After five hours, when well over half of the entrants had finished, she suggested that Oscar drive the course, to check how you were doing, and Oscar suggested that your mother needed to relax, and then she told Oscar to get in the car and go check on her boy.

Fifteen feet from the finish line you limped up to your mother and Oscar, waiting. You were exhausted, and she could see the right side of your body wasn’t working too well. She could also see the joy in you. You told them about the race, how wonderful it was, how cold you were, how you were going to do more marathons, and your mother was happy and relieved, but she also couldn’t help hearing people screaming all around her.

“Cross the line! Cross the finish line!”

Your time was 5:39. There were 101 finishers. You were 96th.

It’s late afternoon and the last light of day is casting long shadows on the snowy streets of Rhinelander. You’re getting a ride home today, so you have a little time to chat. You’re sitting in Culver’s, home of the ButterBurger.

It’s a Wednesday, and you have just finished another day at Drs. Foster and Smith. You’ll have frozen pizza for dinner and tomorrow some more canned chicken with coleslaw. You bought the can of chicken for $2.39 at Walmart and the bag of coleslaw at Trig’s for 99 cents. You’ll get two meals out of the chicken and at least four out of the coleslaw. You’re good with money. You estimate you save $2,000 a year in cab fare alone. You have more than $50,000 in your retirement account. You had more once, from the insurance money awarded after your accident, but your retirement account means much more to you. You worked for it. Your credit rating is “excellent.” You have a platinum credit card. Those are things people don’t know about you.

They don’t know that you traveled to Las Vegas alone years before you made the trip to run the Thin Mint Sprint. You had intended to meet a woman you’d met online there, but it hadn’t worked out. And once you took a bus to Nashville for the same reason, and that hadn’t worked out either. They don’t know that you met someone who had also been in a psychiatric ward once—after you came home following your suicide attempt—and that you have kept in touch with her, through her problems with drugs and her troubled marriage, and that she asked you to train with her for a half marathon (this does not make your mother happy).

You know that disappointment hurts, but that nothing hurts as deeply as the injuries people inflict on themselves. You talk about terrible acts of violence in the world and you say that people who can’t express themselves, who feel as if they can’t tell the world who they are, those people are driven to terrible sadness and can do terrible things to themselves and others, and you sound more like a philosophy professor or a priest than a warehouse dummy.

You talk about thought and language and the Romanian woman you met online and you say “Good day” and “How are you?” in Romanian, then admit that if the conversation goes much beyond that, you’re in deep trouble. Even though it’s late in the day, and you’re tired, your smile is bright, and infectious.

You know that taking action—whether it’s reading history or reciting poetry—expands the mind, and that running conditions the body and expands a man’s world, and that a man can take pride in the things he does, as long as he’s doing things, and you sound like a therapist, or maybe like someone who once tried to commit suicide and then learned the folly of his thinking.

And then you say for a long time you wished you had a girlfriend but now realize that women your age usually have kids, and those women want someone with a car to help take those kids to soccer practice, and that without a car you would just be a burden, so you have accepted that you’re not going to have a girlfriend. And you sound like a lot of other people who put themselves in boxes because they’re afraid.

You feel bad for people who don’t enter races because they think they won’t do well. Does that make any sense? you ask. How are you going to do well if you don’t try?

You know that speed and distance are the standard measures of a runner’s success, but that like a lot of standard measures, they’re wholly inadequate to measure your experience. They’re wholly inadequate to measure you.

In almost 18 years, you still haven’t been to a company picnic or the employee appreciation luncheon. You don’t go because you know you make people uncomfortable. Running is one thing—you’re one among many, you don’t have to chat, and anyone who is uncomfortable, you’re not going to see again anyway. But life is something else. What use would it be, you showing up and talking about yourself? What good could that possibly do anyone?

Bobbi Jewell almost screamed when you nearly flew off that treadmill next to her at Anytime Fitness nearly three years ago, but she helped you adjust the settings and watched you go four miles. And then she watched you go four miles the next time you were both there, and the time after that. She watched you add the elliptical trainer and the stair climber.

Bobbi is the owner of a travel agency in Rhinelander, and you stop by her business—it’s your first stop once you get back in town from running trips—to show her your medals, your bling. You don’t know how much you inspire her.

Marko Modic, your old pal from the warehouse, got promoted a few years after you started together. Then he got promoted again. Today he’s head of human resources at Drs. Foster and Smith. He says you’re smarter than 99 percent of the people at the warehouse, and he’s including your supervisors and his.

He says you have changed, but in subtle ways. He says that before you started running, you would never, ever talk about the accident. Now, especially if it might help someone else, he says you’ll admit that you went through a bad time in your life, that your doctors said you’d never be able to walk or talk, and that if someone else is out there and a doctor says that to him or her, then that person should find another doctor.

Marko has bad days. Who doesn’t? And when those days come, he thinks about you. He thinks about what his old partner from the warehouse floor has endured, and how he’s turned out, and then Marko takes a breath and he knows he’ll be fine, if he just does something. He thinks about you and he takes a step forward, and you don’t know that.

Five years ago, a couple down the road from your mother in Kennan had a 50th anniversary party and they got a visit from their grandson, Johnny, who had been badly beaten and suffered brain injuries. They called your mother and asked if they could bring Johnny over, if he could meet you.

He was having trouble speaking. He wanted to know how you had learned to talk again. You told him that your mother loved musicals, and that vocalizing, that twisting your tongue around those unfamiliar sounds, helped you. Maybe that helped him. You don’t know.

Your brother Eric started running just two years before he got you into the sport. A colleague told him he would like it. “Same old story,” Eric says. “Somebody is running and she tells somebody else. Simple. And I tried it and I decided I like doing something besides nothing.”

Eric runs only once or twice a week, a handful of 5K and 10K races a year. He says he was shocked when he heard you were planning to run a marathon, but he’s not shocked at your success.

He says he never thought about what you could do or couldn’t do, or your particular struggles or successes. You were just his little brother, and something happened, and you and the family dealt with it. It seems like everyone in your family is sort of hard. But when he does stop to think about your running, yeah, it’s something. “Of course it’s changed him,” he says. When he begins to doubt himself—in running, or in anything—he thinks about what you have done. So yeah, of course it has changed Eric, too. Do you know that? Maybe, maybe not.

There’s a lot you don’t know. You don’t know if you’ll attend the company picnic this July, and you don’t know if you’ll stop in at the employee appreciation lunch at Christmastime. You don’t know if you’ll find love. You kind of doubt it. In the past 20-some years, you have donated 12 gallons of blood. Nine to the Red Cross and three more to the Community Blood Center. You know it feels good, and you like the free cookies, and you like chatting with the nurses at the RiverWalk Center. Twelve gallons. You know it’s doing good. But you don’t know how good. There’s so much you don’t know.

You will deteriorate. You have scar tissue at the base of your brain, and you live with pain. When it’s humid, your scar tissue swells and you get tremendous headaches. You might start losing a step tomorrow. You might start losing a lot of steps tomorrow.

Or you may not. You know that researchers have put brain-injured mice on “treadmills,” and those exercising mice recover cognitively faster and more fully than nonexercising ones. You know that a doctor named Steven Flanagan, M.D., chairman of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center, figured that out. He and other scientists suspect the recovery is due to exercise-induced chemical production in the brain, chemicals that promote recovery. You know that along with this there’s a growing body of evidence suggesting that people with brain injuries also may recover faster and more fully if they exercise. You know that doctors around the country recommend that patients with brain injuries, when they are able and under supervision, increase their levels of physical activity. You know that it’s worked for you, that your mind and body have improved, because of running.

You don’t like to talk about your brain injury, or recovery, or what was, or what might have been. But you want people—especially people who are going through what you went through—to know that things can get better, that if things are getting a little better for you, they might get a little better for them.

Your mother believes you are better, and happier, since you started running. She talks about it three days before the shortest day of 2012, sitting in her kitchen, drinking coffee, four days before she and Oscar will drive to Rhinelander to pick you up, take you out for Chinese, and bring you back here to the farm.

She says you feel it’s a blessing you don’t remember your life before the accident, that it would only have made the past 39 years more difficult. They’ve been difficult enough. She says you would have been anything you wanted to be—a doctor, or a lawyer maybe—if that man hadn’t driven his truck into you. She says you love learning and that it’s got to be frustrating being a warehouse dummy. She says she wants you to return to the farm because you love the farm, not because you’re frustrated in Rhinelander.

The first morning at the farm you’ll wake at 4:30 a.m., as you do every morning, and you’ll read in bed (lately you’ve been reading about the American expedition to Siberia after World War I) and then play some cribbage with your mother and Oscar, and then you’ll go take care of the horses and chickens—you walk in a straight line from the house to the barn now, since you started running—and then have breakfast and then help with some bit of construction. Insulating the barn, straightening porch timbers, then pinochle, dinner, a movie on TV, and then it’s bedtime. At some point in there, you’ll go for a run.

Your mother drinks coffee and talks about the jalape?os she pickles, and says there are great kids who don’t become good boys and good boys who don’t become fine men, but you have been all. She says she’s not sure you would have developed into the man you are without running. In fact, she doesn’t think you would have become quite as independent and confident without it. She says you might beat your time by a couple minutes or a couple seconds, but that you will beat it. She knows that improvement might not mean a lot to many people. But it means a lot to you. It means a lot to her. She was an idiot to have fought you on the running, to have doubted you. She knows that now. Your mother doesn’t have difficulty seeing the idiocy in others, and she doesn’t have a hard time seeing the idiocy in herself.

Your mother is a hard woman who has no time for religion, not since she learned about the priest who refused to convert her Lutheran mother, who was pregnant, to Catholicism before she married her husband in the church. The priest told your grandfather that your grandmother was a whore and that her baby would be a bastard.

Your mother is a hard woman who has no time for religion but who is sure we should all seek God, to try to understand what our gift is, to be useful. She says her gift is not panicking in difficult times, in being good at acceptance. She says your gifts are patience and perseverance. (You disagree; you say they’re persistence and stubbornness.)

Your mother sits in her kitchen and speaks of death and mercy and how she was so wrong about running and about the futility of lamentation, and after three hours, she admits that she cried for you once. You were 10 and she realized one afternoon that you would never whistle. It was so stupid, she says, after all you had been through. But she couldn’t help it. She bawled like a baby, because you would never whistle.

People who feel sorry for themselves? She understands. We all encounter injury and illness and loss and change, and we’re all scared and sad and hopeless. She has certainly been all those things. And the moment she bawled like a baby might serve as an object lesson in how we all—runners and nonrunners, brain-damaged and life-battered, blessed and cursed, teenaged loan sharks and high school physics teachers alike—might handle those moments when we want to give up.

“I have sat in a bathtub full of bubbles having a glass of wine, crying and feeling sorry for myself,” your mother says. “Then I got out of the goddamn bathtub and went to bed and got up the next day.”

You love running for how it makes you feel. You love it for the endorphins, and how it’s something that’s hard, and that you can get better at. You love it because at the starting line, you can chat with anyone and so what if it’s a little uncomfortable, you’re not going to see them again anyway. You love it because it has changed you. You walk straighter now and you feel stronger, and you like how you can check out pretty women in shorts and no one seems to mind. You love it because running makes you realize that you were living in a box until a couple years ago—a safe box, but a box, and that since running, you see you’re as good as anyone else, maybe not as fast, but trying as hard, improving as much—and having as much fun. After you finish a race you stay at the finish line, and you yell encouragement at the people still competing—the slowest, the fattest, the people with the most to gain. You know how they feel. You know they’re winners, even if they don’t.

For your second marathon, you ran Disney, in Orlando, in January 2012. You finished in 5:59, almost 20 minutes slower than Eagle River. But it was warm in Florida, much warmer than you expected. And you ran into a fence at mile eight—in spite of all your training, your weaker right side still throws you off as you tire—so you basically limped the last 18 miles. You did it because you’re stubborn and persistent, and because you had entered the race, had grown used to the rewards of racing, and you had decided damn if you were going to fly back home to Rhinelander without a medal, without bling.

You run five days a week now. When you’re tired, your right foot flaps a little bit, and it lands funny, but it’s not too bad. You have finished six 10Ks, a half marathon, and three marathons. This year, you’re going to run the Journeys Marathon in Eagle River for the third time, and you’re shooting for a 4:22. Ten minutes a mile. You think you can do it. But you don’t know.

One thing you do know, something you have learned since you ran that first 5K in those floppy tennis shoes: You’re going to run more races. You’re going to fly to places you never would have before. You’re going to meet people you never would have met, say things you never would have said.

And you’ll be fine.

Something else you know, something else you learned from running: That solitary, hard life you spent so much time and energy building? It’s not enough. It never was.

You want more.

Story Update · December 15, 2016 Steve Friedman’s story about Bret Dunlap was a finalist for a 2014 National Magazine Award in feature writing. The overwhelmingly positive reaction to the piece shocked Friedman, who says, “I’ve never had that kind of response.” It was obvious that Dunlap’s ambition and perseverance struck a chord. “He wanted more, and realized he didn’t need to set limits on himself beyond the profound ones he already faced,” Friedman says. “The limits we set on ourselves are the really confining ones.” Dunlap dealt with additional hardship after the story came out, according to his mother, Barb. Just over a year ago, he had to put his cat, Taffy, down, then a horse stepped on his foot, which sidelined him from running and his ability to get to work. Following that, he lost his job when the Drs. Foster and Smith warehouse was sold. After that, Dunlap moved back to his mother’s farm. He’s since recovered from his foot injury and now, in addition to gardening, mowing, tending to the animals, and splitting logs, helps Barb as she copes with her own health issues. “If you’ve met Bret, the idea of him with an ax and wedges would scare the bejeebers out of you,” Barb says. “But he’s getting better at it.” Earlier this year, he ran the Rhinelander’s Hodag Run for Your Life Half Marathon in 2:14. His 2017 goal is the Journeys in Eagle River Marathon. “I’m doing alright,” Dunlap says. “For a lot of years I was getting up, going to work, coming home, and it’s a little hard transitioning, but I’m doing better. The other day I took a couple hundred pounds of squash to the food pantry. I’ve been in classes to become a chief election official for the village of Kennan. I’m staying busy and keeping up on my running. Nothing really too exciting, but I’ve got the confidence that whatever comes, I’ll be doing pretty well.” –Nick Weldon

You Might Also Like