The Boys Who Made Me

I loved three boys in Alabama. Two of them are now dead. Colt is the one who’s still alive, though I haven’t seen him in fifteen years. Each of these boys mesmerized me in their own way. I remember them perfectly captured in the snow globes of their youth—not yet men but already being shaped by masculinity, and what it wanted them to become. My three Alabama boys showed me what being a boy meant, and I was taking notes.

As an adult, I’ve become critical of straight, cisgender men, especially those whose violence and entitlement harm the women who love them, society at large, and themselves. In a way, it’s a bit shocking that I consider men my muses. My novel, Boys of Alabama, looks at masculinity through the eyes of a teen boy who moves from Germany to a small Southern town, where football and snake-handling churches rule. But when I think back on my youth and the pull these three had over me—the pull they still have—I know that’s what they’ve always been. My Alabama boys. My muses.

To be around them was an education. Like when Colt parked his car at the edge of a cul-de-sac and guided me out to the golf course in the middle of the night. He grabbed my hand and led me through the thorns and bushes until we hit the perfect crew-cut grass of the 9th hole. As we stepped into the rich, manicured paradise, it felt like we’d entered a new world: shaved hills bathed in sodium light; small pods glossy and clean; a deep Alabama blue surrounding us. This was trespassing, but Colt was never scared.

His breath smelled sharp as he shook his cup of Dr. Pepper and crushed ice, whiskey swirling through it. Through him. He hummed Garth Brook’s “The Dance” slurred and slow as we walked. I liked to watch him move through the damp night. I can do this, I thought as he pulled me into a slow waltz near the golf ball cleaning station. This was romance. Like the movies. His bangs a perfect swoosh. His grin cocky and encouraging. My name in his mouth as he said it over and over and over against my ear, stumbling, his arm heavy over my shoulder.

In the back of my brain a thought: This is how a boy touches a girl. This is how a boy sounds when a girl touches him here and then here and now here behind the shell of his ear. This is how a boy blushes when he’s nervous. How he asks a question with his body. How a boy determines what is his to take.

I catalogued the things he had that I saw myself losing: flat contoured chest underneath a crimson polo, boney hips jutting against my palms, curling dark hair on his thighs. My body was suddenly a thing a boy wanted. What a confusing experience, to want to be the thing that wants you. I felt his desire in the air between us. He reached out and pulled me into him, and I turned something off. I turned something else on.

People said we made a cute couple. They said it so often, it must have been true. He gave me a heart necklace on a chunky silver chain with a toggle clasp. A gift for a girl. This could be something I wanted, I thought as he fastened it.

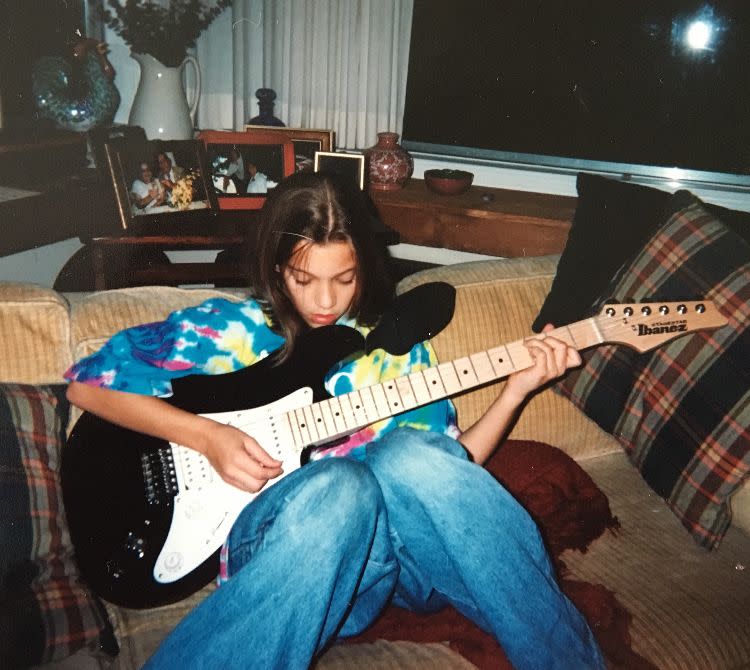

I loved to buy him presents: baseball caps, wallets, video games. Just a few years before, I’d refused to shop outside of the boy’s section in department stores. Those aisles still felt familiar. I knew what to buy for a boy. I didn’t understand what I was supposed to want as a girl. The pinks, the florals, the frills—I found it all appalling. But the spray of Polo Blue into the air? That was how I wanted to smell. Colt showed me how to pour Coca Cola over brand-new Crimson Tide baseball caps and then rub them in the dirt and set them outside for 72 hours to wear them in. He had many tricks like this, tricks boys like him seemed to just know.

The summer of my sixteenth birthday, I was surprised by my own reflection in the mirror. My transformation had been slow but suddenly seemed complete. Hair that touched my shoulders. Wet lips that tasted like strawberries when I licked them. I pulled at the edges of my shirt. Too short in the waist. I wanted to ask the mirror who this new person was. In my mind, I still had my twelve-year-old body, gangly and curve-less, dropping into a halfpipe. Baggy pants dragging their hems across the floor. A shirt so big I could sit my entire body inside of it.

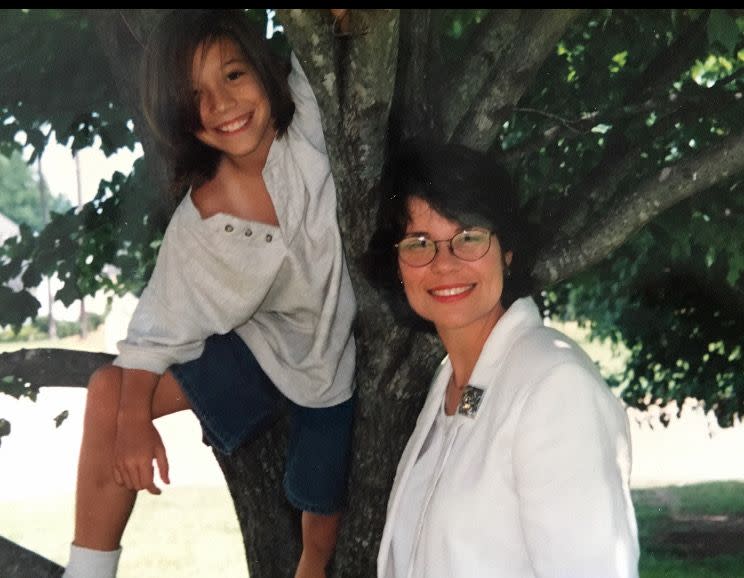

You look so beautiful, my mother said as I stood before her in a dress, panic rising in my chest. Colt stood in the corner with khakis and a wrinkled blue button-up shirt. He looked handsome. I saved the image in my mind. The outfit. The stance: hands in pockets, leaning against the wall. This is how a boy waits for a girl.

Before Colt, there was Mason, the first boy I loved. He is one of the dead ones. We were nine when we met. He drank cold milk in the middle of hot afternoons and smelled sour but also kind of sweet, like Kool-Aid crystals. His younger brother, Little Bill, used to follow us as we skated through the empty University of Alabama campus in the scorched heat of summer break. Little Bill is dead now, too.

Mason lived like he was immortal, like nothing truly bad could ever happen to him. He was the first person to show me a gun in real life. He slid a rifle out from under his bed during a booming thunderstorm. Smooth red wood and dark metal. I was terrified when he pointed the barrel at my face and whispered, bang. Lightning cracked open the clouds. Neon white slices of sky. Mason threw back his head to expose the freckles climbing up from his collar and over his neck. It ain’t even loaded, he said.

Mason made cigarettes out of notebook paper and cotton balls and bits of grass the lawn mower cut up. We smoked them at the creek behind our houses, where we’d hunt water moccasins. Mason saw me how I wanted to be seen. He brought me to hang out with his rat pack of boys like he didn’t see a difference between me and them. The other girls he ignored. I was an exception. Chosen.

I would observe Mason, a ringleader among his friends. This is how a boy shoves another boy when he’s embarrassed. How a boy throws his skateboard against the pavement when he fails at a trick. How a boy convinces his little brother to ride his bike down a dangerously steep set of stairs, and how he laughs when he crashes into the bricks. How a boy calls another boy names with endearment, like a joke, like he loves him. How a boy hugs the same brother he laughed at, crushing him hard against his sweaty, white ribs, planting a kiss at the top of his curls.

I learned of Mason’s death over text message when I was in college. It had been years since we’d spoken. He was around twenty, but in my mind, he is forever eleven, dirty and wet from the creek, gummy scars glossy on his hands from a fishing accident, eyes wide with excitement about whatever scheme he was cooking up.

I think about the promise of boyhood, especially Southern boyhood, and the kind of country-fried future boys are promised if they make themselves in the image of man. Mason never got to the other side of his boyhood. And neither did I. He died and a part of me died, too.

Sammy was the second boy I loved. A goth kid with paperwhite skin and crow-black hair, he wore chokers fashioned from clipped panty hose. He tried to kiss me once, and I let him. It felt like we were two boys, kissing at night, as the crickets screeched and the humid air held us. He’s gay, I thought, before it occurred to me that I could be gay, too.

Sammy lived on chicken nuggets and diet soda. He played the drums and beat on every surface like it was his snare. We used to watch movies on a big-screen television in the dark of his dad’s double-wide. His mother would drive us in her pickup truck into town where we’d skate, finding stairs to jump and handrails to grind. She took us to Montgomery so we could go to Hot Topic and get MxPx patches to iron onto our backpacks and hoodies.

We listened to Smashing Pumpkins B-sides and stared at his ceiling and talked about getting out of this place, a town too small for us. Though Sammy never did leave. When I heard he’d died, it had been years since I’d seen him. Like Mason, he is still a boy in my mind. Forever fourteen.

A tomboy is how grownups described me back then, but it never seemed quite right. My desire colored over the edges of that tidy term. I did not want to be one of the girls garlanded at First Communion in a white dress, clutching a wreath of baby’s breath that my mother picked out. No. There I was trying to pee standing up in the bathroom, a hot stream of piss on my thigh, pooling into my socks. There I was waking up from a nightmare in the middle of the night, my consciousness rocketing back into a body that said girl when all I wanted was one that said boy. I had only the binary at the time. Nothing seemed to exist in between.

Each of these boys told me the same thing: You’re not like other girls. They said it with approval and relief. Their compliment felt like the highest honor. I was special because I was like them. They did not posture around me or treat me like a girl, as they would say, and for that, I felt grateful. It validated my growing suspicion that I was genetically and spiritually different from the girls I knew. I spent so much time looking at Mason and Sammy and Colt that I tricked myself into thinking I was them. I’d see Mason’s body in front of mine, pumping down the street on his skateboard. My body was his body, until the moment I caught my actual reflection in the mirrored store windows we cruised past, shocking me back into myself.

The masculinity I carry in my body today comes from each of them. I’ve returned to the butchness of my youth. I wear men’s clothing and keep my hair shaved short. Though I have not shaken my female pronouns entirely, I lean into a more expansive gender identity that colors over the binary. I have embraced the boy in me. And when I think about what a boy is, there is Sammy leaning back on his bed. I see Colt walking through the halls of school, tanned and humming a country song. And there is Mason, mischief filling his eyes, dropping in on an 8-foot halfpipe. When I go home to visit Alabama, every street holds a memory. I see us walking through our neighborhood at dusk, skating over hot concrete in a wet afternoon, sneaking onto golf courses in the middle of the night. I choose to remember all three of them as they were, buoyant and hopeful, spring-loaded. Those boys are my stories, and I think, in one way or another, they will find their way into each one I’ll ever try to tell.

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

You Might Also Like