We Need Black Men to Start Believing in the Electoral Process Again

When I was a kid, I used to watch my father do amazing things for people all the time—he’d fix roofs, lay drywall, pour cement for entire driveways. We were extremely poor, and I could never understand why. I thought: My dad is an anomaly. How can you be so great as a person and still suffer from poverty?

As I grew older, I realized my dad was not an anomaly. Most Black men his age were similarly situated but were crippled in some way: My dad, for instance, earned a felony when he was a young boy for defending his mother against white supremacy. Knowing that his struggles were all too common for Black men and watching America snuff out his greatness were my marching orders and the reason I fight for the betterment of my community.

I wound up doing campaign work for a long time, and one thing I noticed right away was that most of the people who determine what’s said about politics generally, but progressive politics more specifically, are white men. The messaging they convey doesn’t speak to my lived experience as a Black man. It’s not motivating to me or to the brothas I know—uncles, cousins, friends, men like my father.

It is well-known that voting is a habit that’s formed when resources are spent on it, and Black men aren’t a priority when it comes to spending money on elections. That was the genesis of the Black Male Voter Project. Our goal isn’t just to make voters out of Black men but to foster this idea of voting on issues that are important to us. We don’t outright support candidates; we support issues important to Black men. We’re seeking to combat the narrative that Black men are apathetic toward politics.

Being a Black man in America is a political statement, and it is impossible to watch politics from my body when the result of so much of the politics of this country has been the subjugation of me and folks who look like me. You can’t discount the impact that’s had on the mental health of Black men, either, and yet mental health is not considered part of the fight for revolution as it pertains to white supremacy. Imagine what hundreds of years of slavery have done to the psyche and the soul and the makeup of Black bodies in this country.

There’s a direct correlation between voting and people’s health, especially for Black men. We know we’re overrepresented in the prison population, which means we are less likely to have voting rights. A Florida prison system did a study a few years back, and they found that people with restored voting rights were less likely to go back to prison.

Every time that I’m silent about inequality, I think about my mother, who would pretend to laugh—to lessen the impact—when she would tell me stories about being sprayed with a fire hose when she was nine years old for no reason other than being downtown after dark. She couldn’t run and hide because she also had groceries for her siblings in her arms, and so she had to pick up the groceries while being sprayed. The white man who did it was still in elected office as the fire chief when I was growing up. Whenever I’m silent, I feel as though I’m selling my mother out.

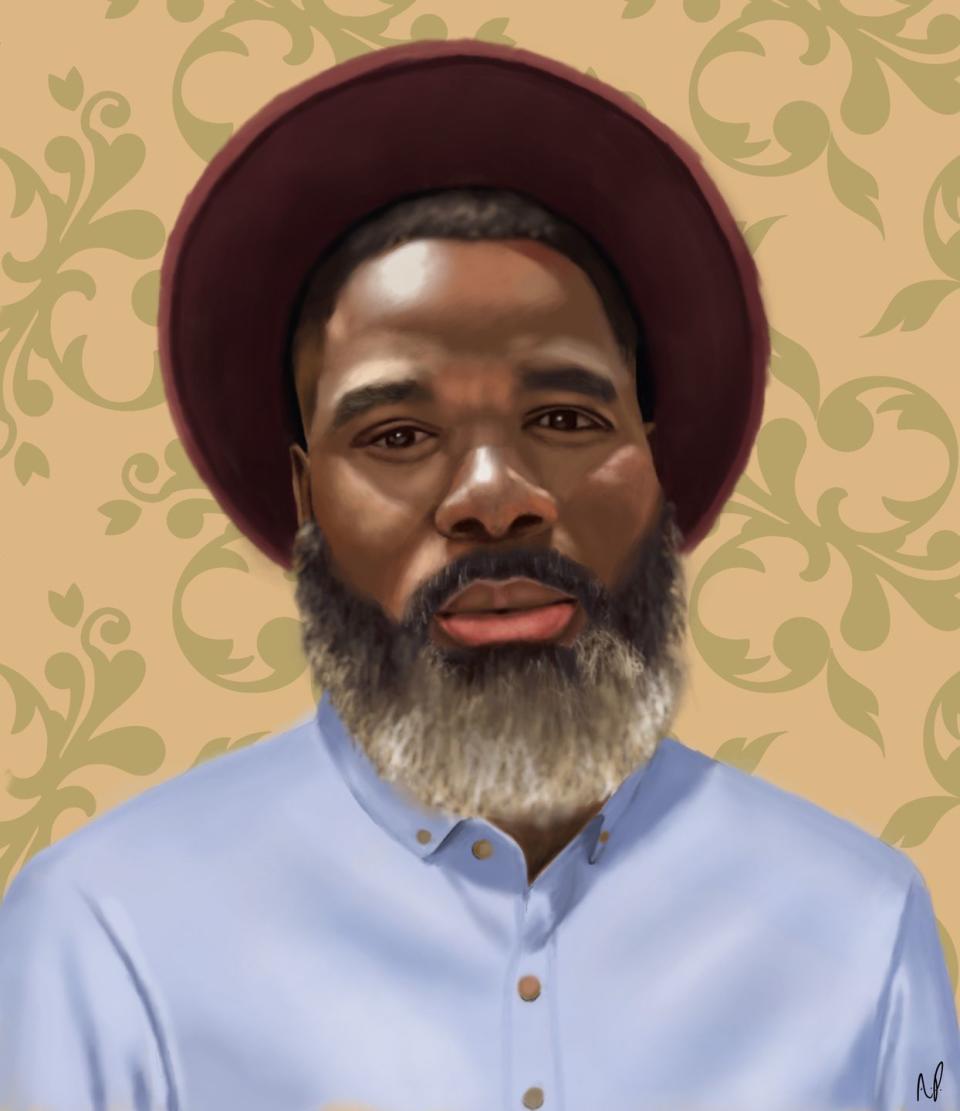

How we define success with our organization, in the end, is more complex than simply getting more Black men to vote. We’re building long-term relationships. We hold focus groups called Brothas Be Voting and populate the room with brothas who don’t normally participate in politics, people from the street and from underground economies, so we can hear what the barriers are. That way, we can work to remove them and help Black men start believing in the electoral process again. —As told to Michelle Garcia

You Might Also Like