How Black Filmmakers Reinvented the Horror Genre

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In Scream, horror expert Randy lays out the rules for surviving a scary movie: don’t have sex, don’t drink or take drugs, and never say, “I’ll be right back.” If he wanted to cover all the bases, he should have added a fourth survival rule: don’t be Black. Black characters do not last long in your typical horror movie. If they are lucky enough to be given a name or, y’know, any depth of character at all, they are still likely to be dead long before the snotty cheerleader who goes down to the basement in her bra to investigate what that strange noise was.

Even in movies where an extensive body count is de rigueur, the high mortality rate of Black characters has been more than a little suggestive about industry attitudes over the years. It also exposes the inequality of who gets to tell these stories. After all, it took until 2017 for Jordan Peele to become the first ever Black winner of an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

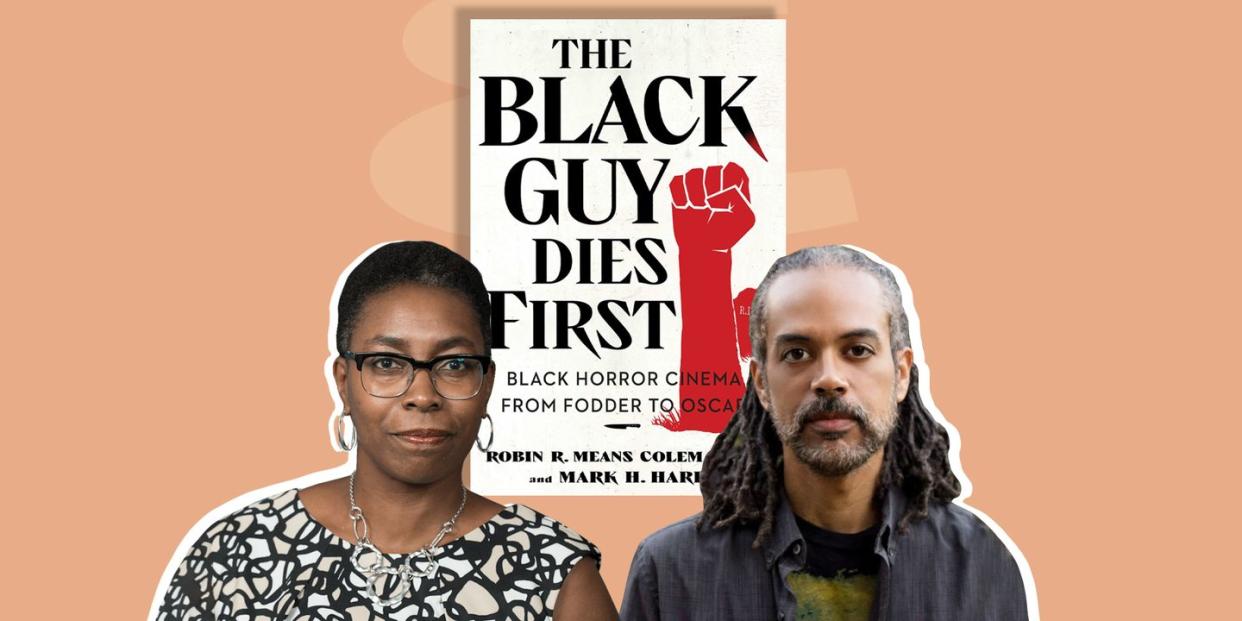

It’s perhaps less surprising, however, that Peele won his statuette for a horror movie. As a new book, The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar, makes abundantly clear, Black people have always been present in horror. From the earliest macabre moving pictures through to modern day terrors, a multiplicity of Black cultures has continuously helped (re)define the nature of the genre. The book is a survey of that evolution’s highest and lowest points, and the story of how American cinema and American social justice are intertwined.

The authors are a pair of leading experts in the field. Dr Robin R. Means Coleman is an internationally recognized scholar with a specialism in media and the cultural politics of Blackness. She is the author of Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (2011). This landmark study of Black horror was made into an acclaimed documentary for Shudder in 2019.

Her co-author, Mark H. Harris, brings a streak of pop culture zaniness to the project. Harris is a journalist whose website BlackHorrorMovie.com has become the key online source for information on the most obscure Black horror. It’s an obsession that’s put to great effect in The Black Guy Dies First, with deep cut lists breaking up the more sober film criticism. According to Dr. Coleman, Mark is also responsible for most of the jokes. In case you were worried that this sounds like a dry read, consider the following point about how movies handle the theme of Black-on-Black violence:

“It would be hard to imagine a White writer broaching this thorny topic, especially in such an admonishing manner, unless they carried a Platinum Level Ghetto Pass—historically held by only three people: John Brown, Mr. Rogers, and Ice-T’s wife Coco.”

The authors make a formidable duo. Speaking to them both, a week prior to publication, I did my best not to ask any truly stupid questions.

ESQUIRE: Publication is imminent. How are you feeling about your book being released into the world?

Mark H. Harris: It’s my first book, so it still seems really surreal. It hasn’t really hit me, even though I have a copy in my hand. I have no idea what to expect. Feedback so far has been great, but I’m basically a new-born being birthed into this world.

Robin R. Means-Coleman: I’m super excited as we approach the release, not just because of the book, but because I’ve been a long-time fan of Mark’s work. His website is a hugely valuable resource. This may be his first book, but that website represents a really smart, witty, scholarly mind in the Black horror space. Our partnership is a decade in the making, but us coming together seems like a really natural pairing.

Some of that partnership can be seen in the seminal documentary Horror Noire, in which you both appear as commentators. The documentary is based on your book, Robin, so you have previous experience in this field. How does The Black Guy Dies First connect with or continue this discussion?

RC: I think the two books are really quite complementary. Horror Noire is a more scholarly book, with a clear, theoretical undergirding that progresses, decade-by-decade, through the evolution of Black Horror and social justice. The Black Guy Dies First is a more commercial book. It’s fun and funny. It’s both a love letter to horror fans and an accessible introduction for those new to the genre.

This is a remarkably funny book, despite the seriousness of the themes discussed. There is barely a paragraph without a joke or a comic metaphor. Was humor essential to this project?

MH: I think it was essential to our approach. It was meant to draw in people who aren’t horror fans, or people who are fans, but who aren’t necessarily interested in the Black horror aspect. We needed to use humor and entertainment to get people in, and then you can slip your message under the door. It’s a similar approach to things like The Daily Show or Last Week Tonight.

$24.99

amazon.com

RC: The parallel between horror and comedy is remarkable. Black horror in particular is infused with the funny. That’s what makes the genre so attractive to me. It draws you in and sometimes it’s super pedagogical, teaching you about Black life and culture and social justice; other times there’s no message at all and it’s purely entertaining. But what is often present is that element of humor. Humor is so much a part of Blackness, and I love that we get to center that. I knew I didn’t want to suck the life out of this really vibrant, dynamic genre.

You refer to the category of “Black Horror” throughout. What does that mean in your book’s terms? Are you talking about movies made by Black creatives, representing Black characters, or simply movies that are aimed at a Black audience?

MH: I would say it is all of the above. I know in Horror Noire, Robin sets up a delineation between Black horror and Blacks in horror, but I think The Black Guy Dies First is a little more general.

RC: There are so many movies in which Black characters are parachuted in as incidental or token characters, and often the Black guy does die first. But those movies are not hailing Black audiences, or speaking to the culture, history, linguistics, or anything to do with Blackness. So I wanted to make a distinction between Blacks in horror and Black horror cinema. The Black Guy Dies First contains some pretty dispiriting statistics. One in particular seems to galvanize the whole project: in a survey of nearly a thousand movies, the Black mortality rate is forty-five percent. What does that say to you about horror’s attitude about Black lives?

MH: That is the driving force of the book. The Black guy dying first may be a campy trope, but underneath it’s reflective of the marginalization of Black characters in the genre. Frankly, it’s not exclusive to horror, but what is unique about horror is how the marginalization is very in-your-face, because the character typically dies in a very violent manner. Historically, Black characters are pushed to the side. They are rarely the hero or the person saving the day. At best, they are the sidekick who dies at the end.

Considering all of that historical contempt, what is it that attracted you to horror, or kept you watching?

RC: It comes back to Black horror versus Blacks in horror. Black horror movies don’t always do us like that. We live, we survive, we come up with radical solutions and retribution to the ways we are treated in the real and the imaginary. Black horror is powerful because it disrupts those treatments and says we’ve got something else we can imagine about the ways we value and hold up Blackness.

MH: There’s probably a significant portion of the Black audience that shies away from horror movies with Black characters, because images of violence against Black people are triggering to them. It’s certainly a hurdle to some people’s acceptance of the genre. Robin and I have a long love affair with horror, though. The movie that kicked it off for me is George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. I remember being twelve years-old and marveling at this black and white movie that seemed ancient, and the lead was this Black guy bossing and slapping around the lead [white] people. It seemed shocking to me that such representation could happen what seemed centuries ago, at least to me at the time. The fact that you could have a story that doesn’t have to end happily—that struck a note with me. You can have something that reflects reality more than I usually see on the movie screen. That stuck with me and I’ve been into horror ever since.

$46.50

amazon.com

RC: That doesn’t mean that Black horror movies have to always be about a message. It’s absolutely lovely when it’s purely entertainment, and I love that so much. But there is something interesting about when a Black character is kicking ass and taking names, and we can say yes, that is the radical solution to the absence of social justice in the real. Maybe we can get it in the fictional.

Romero often claimed that his casting of the Black actor Duane Jones wasn’t political or racial commentary. Do you find that believable?

RC: I don’t. But the other thing that’s interesting is that Romero has often spoken about how his films are social satires or commentary. So, over the years, it’s as if we’re supposed to believe that Duane Jones’ casting is the one exception in all of this very thoughtful reflection on where the US is socially. Romero shifts from a claim that it was colorblind casting to the claim that it was completely apolitical. I think he’s blurring two different things. Regardless of what Romero says, Duane Jones still shows up in that movie as a Black man in the character Ben. There is no colorblindness in how the audience sees and reads Ben. That’s a better focus than what Romero may have intended.

The book chronicles decades of movies. There are highlights, but also many, many lows, as compiled in these great lists of wacky underground movies. Titles like Urban Cannibal Massacre (2013), Honky Holocaust (2014), and Buttcrack (1998)—a film about voodoo and a ghost with an exposed ass-crack. How on earth did you find all of these movies?

MH: I think that’s a line of questioning for me. Robin is far too busy to watch those movies, whereas I have too much time on my hands. Since I started my website, I’ve been obsessively trawling the internet. I sometimes search IMDB, find a Black actor, and wonder, “Have they ever been in a horror movie?” It’s kind of an endurance test sometimes. There’s a lot of dreck. As much as I love horror, a lot of the movies are terrible, especially in this era when anyone with a phone can make a movie. It’s a lot of work, but I’m doing my part.

RC: For me, it started with the first edition of Horror Noire. I was at the University of Michigan and I was really lucky that their library has one of the country’s largest holdings of horror films. A couple of librarians are big fans; they started hoarding this collection, and they were able to reach out to contacts to find these really obscure movies, sometimes shot on low-quality cell phone footage. They would turn up at my office, sometimes wrapped in tinfoil without even a DVD case. We had a television lab in my department, with all these monitors. I’d have two or three movies running at a time, watching horror films simultaneously to get through them and do the analysis. It was a cool job to have.

At the other end of the quality spectrum, we have Candyman (1992). Of all your analyses in the book, this is the one that most grabbed my attention. I thought of Candyman as a landmark moment in Black horror, but you highlight its problematic aspects.

MH: I would say first off that we both appreciate Candyman as a horror film. It’s effective and Tony Todd gives a wonderful performance in the title role. But in terms of Black representation, there are some problems. There is a historical trope of Black men lusting after white women that feeds into it. That can cause some discomfort. The other thing is how the movie centers on Virgina Madsen’s character, a white college student who ventures into a Black urban area. The movie is more about her plight in this “urban jungle.” It’s like the modern urban version of Tarzan, with white people traveling into a jungle populated by bloodthirsty savages.

RC: The other position we speak about is how poorly women are represented in that movie, Black or white. There are tropes about “feminists” being hardscrabble, smoking cigarettes, and talking back to men. Poor Virginia Madsen has to do all this and then get checked by her male colleagues. It’s a film that falls into well-worn tropes around race and gender.

MH: There are shortcomings there, but as Black horror fans, we learn to separate the issues from the movie itself.

RC: Absolutely. Tony Todd snatches the film from those limitations. He elevates it into something gorgeous. In the Horror Noire documentary, he tells a story about how Kasi Lemmons told him he’d be seen as Candyman forever. That’s true, as it’s turned out.

Out of all the films you critique in The Black Guy Dies First, has there ever been a sea change like Jordan Peele’s Get Out?

RC: For a horror film to win an Academy Award, that’s always a showstopper. When that happens, people take notice. Peele is carrying the horror genre forward in Get Out, Us, Nope, and future projects coming through his Monkeypaw Productions. But there’s also an impulse to duplicate that, and we’ve been here before, where other directors try to capitalize on momentum without the same quality, investment, and diversity in the room.

MH: Get Out is that rare horror movie: a critical darling that did tremendously at the box office. It came out right after Trump’s election victory and really struck a chord with American audiences, Black and white, who were really feeling a sense of frustration with how things were going. I think it touched on topics that people had a thirst for. With that success and Peele’s subsequent movies, Hollywood is trying to ride that train. It’s a double-edged sword. Black creatives are getting more opportunity in the industry, but there are also a lot of get-rich quick attempts to cash in on Peele’s success.

RC: It’s cyclical. We saw it in the 70s with Blaxsploitation cinema; then production companies like AIP would get involved and say, “We’re going to do the low budget version of this and make a few bucks.” So what we’re seeing now are some fantastic horror movies, but also a return to Blacks in horror, with characters parachuted into films that weren’t originally written for Black characters, or people trying to quickly capitalize on the Black horror trend. Our hope is we don’t see that cycle return.

MH: We’re at a crucial time right now. Things can go either way. We can keep elevating and finding new voices in the genre, who can explore new areas. Or we can go the way of Blaxsploitation, in which things got diluted and Hollywood moved on to something else.

Do you see reason to hope that the current upswing in Black representation in horror, or in cinema generally, is here to stay?

MH: I don’t think I could exist without some hope. There is definite progress. I think more Black people have won Oscars in the last decade than in the previous century. I guess it’s just a matter of how well that progress is maintained. The recent Oscar nominations reveal that when movies like The Woman King and Nope and Till receive no nominations, that’s an issue. Especially when Top Gun: Maverick gets nominated for best original screenplay. I don’t know how you come out of that movie and go, “What a great screenplay!”

RC: It’s worth remembering that Black horror has been around for more than a hundred years. Black people’s contributions to horror have always been present, and they’re here to stay. If the measure is its mainstream crossover impact, that’s a different question. There are all these movies that don’t get the big screen splash like Get Out or The Purge franchise does. Things like Rusty Cundieff’s Tales from the Hood (1995) or Snoop Dogg’s Bones (2001). Some are high quality; some are not. But they are often fun or funny, and that’s the most important thing. They may not be recognized by awards or measured by crossover success, but Black people have been front and center in the horror genre for over a century.

You Might Also Like