From a living room in Queens to a global empire: how Weight Watchers took over the world

Eleanor Halls discovers how the Weight Watchers founder Jean Nidetch built up her billion-dollar empire by reading Marisa Meltzer's This is Big

It was 1961 and 38-year-old Jean Nidetch was on her way to her local grocery store to buy, primarily, but among other things, three boxes of Mallomars. These gooey marshmallow treats would soon be stashed under the sink in the bathroom of her home, where, once the door was locked and the children distracted, Nidetch, who at 15 stone was lighter than her husband and happy about it, would consume all three boxes in one sitting.

She was thinking about this when an acquaintance walked past her in the aisle and, marvelling at her physique, asked Nidetch when she was due. Stricken, Nidetch – whose cab driver father had always been proud of having a plump daughter and wife during the Depression – went home, took a bracing look at herself in the mirror, and signed on to a New York obesity clinic. By 1962, she had lost 70lbs and, crucially, kept the weight off.

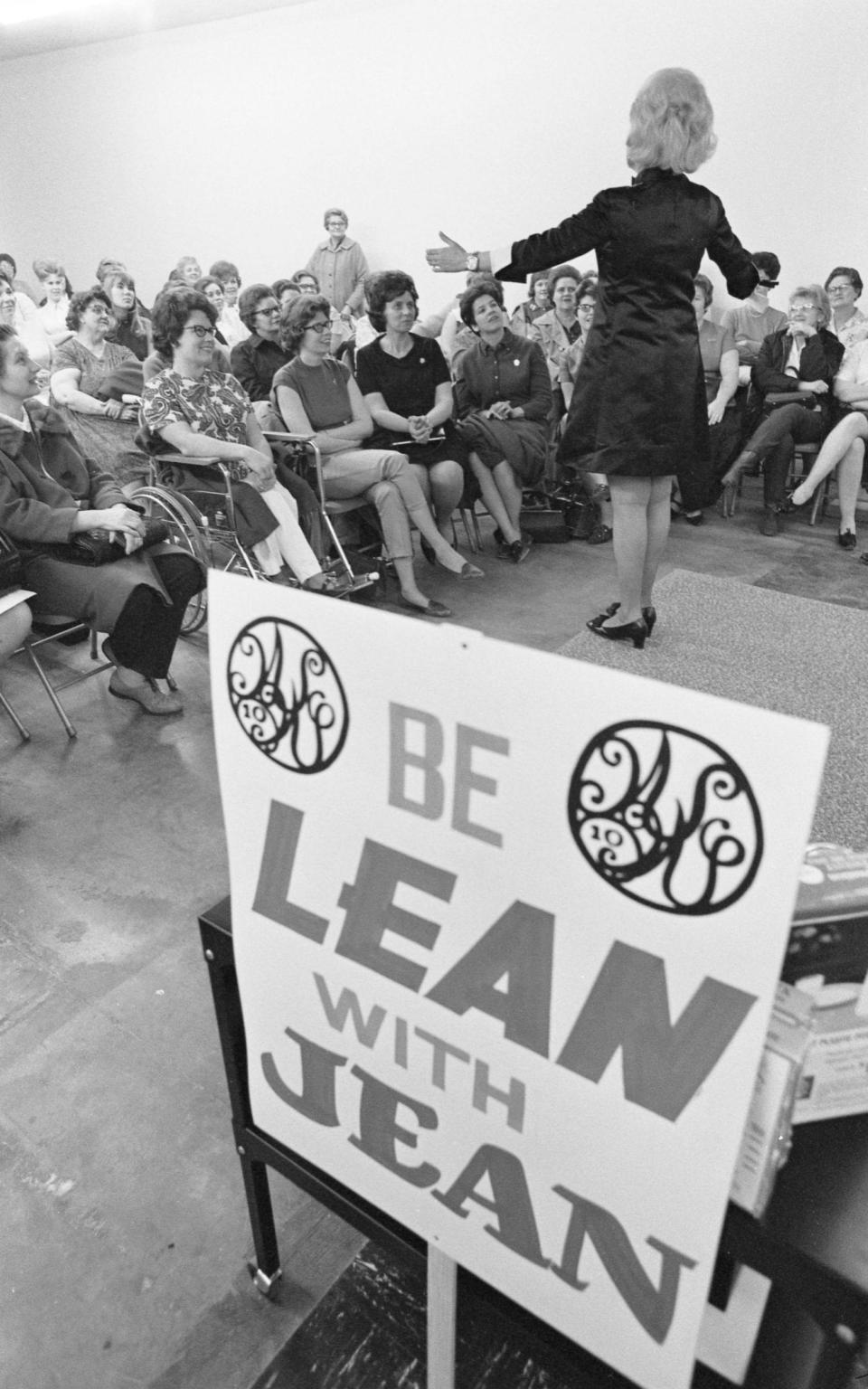

A naturally charismatic and glamorous extrovert who never left the house without an immaculately coiffed bouffant, Nidetch soon became a household name in her neighbourhood for weight loss tips and motivational pick-me-ups, which she dispensed to anyone who dropped by her home. Her motto: “It’s choice, not chance, that determines your destiny.” These drop-ins soon became regular weekly salons, and on May 15 1963, Nidetch had launched Weight Watchers with her first public meeting. She was so confident of her future success that she called it Weight Watchers International.

“Most fat people need to be hurt in some way into taking action and doing something for themselves. Something has got to happen to demoralise you suddenly and completely before you see the light,” writes 44-year-old American journalist Marisa Meltzer in the opening pages of This Is Big, as she describes the moment that turned Nidetch from an unknown housewife into one of the world’s most successful entrepreneurs almost overnight.

The first Weight Watchers meeting had 50 chairs set out – 400 people turned up. By 1966, 297 classes were operating every week in New York City alone; by 1968 the company reported a gross revenue of $5.5 million; and in 1969, the company had 102 franchises and 1.5 million members. In 1978, Weight Watchers was sold to Heinz for $71 million.

Meltzer, who first visited a dietitian as a toddler and “fat camp” aged 10, became fascinated with the businesswoman after reading her obituary in April 2015. She was drawn to the details in Nidetch’s life that mirrored her own – the women were both blonde, both five-foot-seven, both lived in Brooklyn and both Jewish. Meltzer, a self-described “chronic, yo-yo dieter” who has received her fair share of misguided pregnancy enquiries, decided to join Weight Watchers on the spot. She then wrote down a list of questions she wished she could have asked Nidetch, who had died aged 91 of natural causes and with little of her fortune left. The answers, and the fascinating meanderings of Meltzer’s research, provide the backbone of her book.

Nidetch wrote an autobiography in 2010 and a history of Weight Watchers in 1970, but Meltzer’s This Is Big is the first outsider’s chronicle of what is now a billion-dollar global empire, which has spawned magazines, frozen food lines, cookbooks and cruises; an empire so tightly woven into the fabric of American society that no social history makes sense without it. Currently, 45 million Americans are on a diet, and $33 billion (£27 billion) is spent on weight loss products annually. Weight Watchers’ celebrity ambassador Oprah Winfrey owned 5.5 million shares until 2019. Last year, as diet became a dirty word and wellness its shiny new usurper, Weight Watchers rebranded to WW.

The word diet, as Meltzer writes, comes from the ancient Greek diata, or “way of life”. In Europe, plumpness used to be admired as a physical demonstration of wealth, class, and in the case of women, fertility. The word diet didn’t assume its connotation of losing weight until industrialisation in the second half of the 19th century, when men put out of manual labour suddenly found themselves at home and piling on the pounds.

During the two world wars, excess and indulgence were turned into shameful vices that conflicted with national duty. Scales became bathroom staples shortly after 1918, the year that Diet and Health: With Key to the Calories by Lulu Hunt Peters became a bestseller in America. Corsets were phased out, photography swept across fashion magazines, and, with ready-to-wear clothing replacing the bespoke, sizing was now fixed and competitive.

Meltzer’s whistle-stop history of America’s body image is both effortlessly informative and efficiently selective – as a seasoned magazine writer for Vogue and Vanity Fair she knows how to juice a handful of facts with a brisk squeeze of the fist. Nuggets from Nidetch’s autobiography and the Weight Watchers archives are served alongside chunks of feminist theory and juicy asides – who knew Ivana Trump once said “it makes me feel powerful to be hungry” or that Cinderella was Disney’s first “thin” animated heroine?

Every now and again, Meltzer stops zipping through the history books and comes up for air, taking a moment to fill us in on her own experience of Weight Watchers: going to meetings, trying the recipes, even attempting a cruise. She finds it hard to let go of her preconception that Weight Watchers is “one of the most basic, retro, lowest common denominator, least chic diet companies in the world”. More difficult still, she “doesn’t have a good answer for why I am still fat” and is clearly exhausted trying to figure it out. Worse than the actual diet is thinking about dieting, which is relentless.

Throughout the book, Meltzer holds the reader at arm’s length. This is nothing like Roxane Gay’s evisceratingly personal 2017 memoir Hunger, which revealed the writer’s obesity was a symptom of rape. Gay gained weight for protection from the eyes of men – each sentence is shocking to read and must have been excruciating to write. Meltzer, who profiled Gay for Elle in 2017 and refers to her often, prefers not to go into too much personal detail, presenting a curated selection of traumas and micro-aggressions with a shield of detachment. While this allows for a great deal of organic empathy towards Meltzer – she is never one to milk an anecdote for pity’s sake – the emotional roots of the book seem to dangle above ground.

She hints that a seven-year relationship with a man significantly lighter than her was difficult, but goes no further. Her parents, who put her on her first diet aged five, are reproached but never exposed. Her bulimia and clinical depression are merely mentioned. Naturally a reader has no right to demand such personal truths from a writer, but by framing the book as part memoir, Meltzer invites a certain level of nosiness. “Eating, for me, is really about transgression, a rebellion against myself,” writes Meltzer. But what rebellion? I finished the book still nibbling hungrily at all the things left unsaid.

Call 0844 871 1514 to order from the Telegraph for £12.99