The 44 best children’s books and YA novels of 2019 so far

Emily Bearn reviews the best children’s books and young adult fiction of the year. From rollicking adventures to charming picture-books, these are sure to keep even the most restless kids entertained

The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone by Jaclyn Moriarty (Guppy) ★★★★★

Guppy Books (named after the fish, not Darius) is a new children’s publisher that currently operates from an Oxfordshire kitchen table. Corks will be popping at the news that its first book, Gloves Off, a novel in verse by Louisa Reid, has been nominated for the Carnegie. Will its second book – a fantasy by Australian novelist Jaclyn Moriarty – continue the winning run?

The story’s narrator is Bronte, who was abandoned by her parents as a baby, and brought up by her aunt in a cocoon of riding lessons and afternoon tea. (“She hadn’t much choice in the matter: she’d found me in the lobby of her apartment building, rugged up in my pram.”) When Bronte is 10, her parents are killed by pirates. In their will, they instruct her to set off around the world, delivering gifts to her other aunts. “She must start the journey in exactly three days… and she’s to do it alone.”

What’s more, the will is written in Faery cross-stitch: “YOU MUST FOLLOW THESE INSTRUCTIONS PRECISELY, BRONTE! OR PEOPLE COULD DIE.” And so she reluctantly sets off on her 109-chapter whirligig of adventure, during which she survives avalanches and water sprites, and starts to suspect that there might be more to her parents’ fate than the stuffy old lawyers let on.

This is Moriarty’s first book for younger readers, and she seems entirely at home in the mind of her cautiously adventurous child narrator: “As much I was frightened, a tiny part of me, right in the centre of my heart, was also rather excited.” Fantasy lovers will relish the dragons and gnomes, “impenetrable forests” and “various nefarious kingdoms”. But however well trodden the landscape, we never feel as if we’ve been here before. Like all the best fantasy writers, Moriarty can turn familiar tropes into something her own.

Order The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Fowl Twins by Eoin Colfer (HarperCollins) ★★★★★

It is seven years since Eoin Colfer wrote the final instalment of Artemis Fowl, his sci-fi fantasy series about a teenage criminal mastermind whose adventures range from kidnapping a fairy to surviving the Russian mafia. But with 25 million books sold, and a Disney film out next year, the story couldn’t end there – and hey presto! Here is a series starring Artemis’s younger twin brothers.

In The Fowl Twins, Artemis has grown up, and is on a five-year mission to Mars in a “revolutionary self-winding rocket ship” that he built in a barn. The Fowl parents are in New York, leaving 11-year-old Myles and Beckett under the surveillance of their family home’s futuristic security system.

Gloriously Colferesque mishaps abound. Walking on the beach, the twins encounter a troll thought to have supernatural longevity. But unbeknown to them, the creature is under the surveillance of ancient Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye, who has “dedicated most of his 150-plus years on this green Earth to staying on this green Earth as long as possible” – and will murder anyone who stands in his way. “I must find the fountain of youth, he resolved… And the family he would possibly have to murder to access it was none other than the Fowls of Dublin, Ireland, who were not overly fond of being murdered.”

Colfer is a hugely entertaining writer who unravels his plot at breakneck speed while never stinting on the detail. “Trolls are highly susceptible to chemically induced psychosis while also tending to nest in chemically polluted sites… this particular troll’s bloodstream was clear because he had never swum across a chromium-saturated lake,” we are told, in a passage in which our heroes are shot at, kidnapped, and threatened by an immortal Duke and a maniacal nun. Only Colfer could pull it off.

Order The Fowl Twins from the Telegraph Bookshop

Deeplight by Frances Hardinge (Macmillan) ★★★★★

Now sit up straight, for here is the much-awaited ninth novel by Frances Hardinge – and she is not the sort of author you read lying in a deck chair with your fist in a box of chocs. Hardinge, who won Costa Book of the Year in 2015 for The Lie Tree, is known for her dense, darkly fantastical plots, and Deeplight is no exception. As she warns the reader in a disclaimer on the title page: “The laws of physics were harmed during the making of this book. In fact, I tortured them into horrific new shapes while cackling.”

This assault on physics has produced a highly entertaining book. The hero of the story is Hark, a 14-year-old orphan who lives in the kingdom of Myriad, a cluster of islands that were once inhabited by warring sea gods. “They say that the ocean around the Myriad has its own madness. Sailors tell of great whirlpools that swallow boats, and of reeking, ice-cold jets that bubble to the surface and stop the hearts of swimmers.” When his friend Jelt embarks on a quest to retrieve submerged relics that the gods left behind when they deserted the islands 30 years ago, the line between truth and legend becomes blurred: “They say that a coin-sized scrap of dead god can make your fortune, if the powers it possesses are strange and rare enough, and if you are brave enough to dive for them.’

Even by the standards of young adult fiction, Hardinge’s storylines are far out. In Gullstruck Island (2009), birds unravel people’s souls; The Lie Tree is a Victorian murder story in which a tree feeds off whispered lies. But she is a deceptively disciplined writer, and here she untangles her complex story in clear, suspenseful chapters, and contains her every flight of fancy within a rigid plot. Hardinge is not always an easy read – but she is a reliably good one.

Order Deeplight from the Telegraph Bookshop

The World of the Unknown: Ghosts by Christopher Maynard (Usborne) ★★★★★

There are dozens of ghost books competing for attention in the run-up to Hallowe’en – and any with pumpkins on the cover are doomed to look stale by November. But what a treat to discover this relic risen from the dead: Christopher Maynard’s 1977 cult classic The World of the Unknown: Ghosts, reprinted after more than 1,000 fans lobbied the publisher for a new edition.

Older readers may recall the stir that the book caused (“a seminal work of groundbreaking genius”, according to David Nicholls), and the new edition sensibly resists any temptation to tamper with its winning formula. The shiny cover – with a picture of a haunted house and a gusting candle – looks as dated as Worzel Gummidge. But this is an utterly engrossing book, in which nostalgia is key to the appeal. “Many of the different kinds of ghosts that are thought to haunt the Earth and their behaviours are described here,” the introduction explains. “Whether they really do exist is still a complete mystery, but perhaps this book will help you to make up your mind.”

Maynard’s mind seems set, as he talks us through everything from phantom ships to poltergeists in the sort of matter-of-fact tone with which a botanist might describe a herbaceous border. “Poltergeist activity usually happens when people between the ages of 12 and 16 are present,” and “If people are unfortunate enough to see their own doppelg?nger, it can be an omen that they will die in the near future,” are typical of his observations. There is also a helpful section on ghost-hunting equipment: “The temperature of the air is said to drop noticeably when ghosts are around, so take a big, easy-to-read thermometer.” And don’t try to make small talk: “A ghost almost never speaks, even if it is spoken to.”

Order The World of the Unknown: Ghosts from the Telegraph Bookshop

We Are the Beaker Girls by Jacqueline Wilson (Doubleday) ★★★★★

What’s afoot with Dame Jacqueline Wilson, who over the course of 111 novels has dreamt up some of the most memorable stories of family dysfunction in modern children’s literature? In Wilsonland, bullies and abusive step-parents lurk around every council-estate corner; children are liable to depression and neglect; one heroine was even abandoned as a baby in a dustbin. Wilson is a superb storyteller, who appeals to children of every background, and seldom puts a foot wrong. But her fans should be warned. The latest instalment in her Tracy Beaker series – about a child growing up in the “dumping ground” of a care home – contains unmistakable glimmers of hope.

Tracy is now a grown-up. In last year’s My Mum Tracy Beaker, we found her living on a council estate “ankle-deep in rubbish” with her nine-year-old daughter, Jess. But in We Are the Beaker Girls, they are living in a seaside town, above the antiques shop where Tracy works. “We moved in a month ago,” explains Jess, whose narration sets the novel’s infectiously upbeat tone. “We treat ourselves [to ice cream] whenever we make a big sale… And today we’d made an absolutely HUGE sale.” The volatile Tracy has made up with Miss Oliver (“now she’s almost like Mum’s foster aunty”); her romantic life is calm (“Bill asked Mum if she had a boyfriend. Mum just laughed. She says she’s given up on men”); and after being bullied at her last school, Jess is relishing her new start: “When we moved to Cooksea I decided I wasn’t going to be that pathetic girl any more.”

Inevitably, storms sully the horizon – not least when Jess is picked on by a local foster child, who provides all the drama that Wilson fans have come to expect. But at the heart of this uplifting book is the story of the troubled Tracy blossoming into a jolly good mum.

Order We Are the Beaker Girls from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Tzar's Curious Runaways by Robin Scott-Elliot (Everything with Words) ★★★★★

Russia is fertile ground for children's fiction, with novels such as Katherine Rundell's The Wolf Wilder and Sophie Anderson's The House with Chicken Legs recently demonstrating how Slavic folklore can be magicked into a modern bestseller. The Tzar's Curious Runaways, by the former BBC sports journalist Robin Scott-Elliot, weaves a similar spell.

The heroine is 14-year-old Katinka, a ballerina with a hunchback who belongs to Peter the Great's "Circus of Curiosities", where she has been performing since the Tzar's men kidnapped her from her parents at the age of six. "She was used to the way people looked at her and didn't see her... In their twisted minds, she was 'a freak' because she belonged to the Tzar's collection of people who were different."

But Scott-Elliot's narrative begins after the Tzar's death, when Katinka and her fellow performers are at risk from the ruthless Empress, who wants the circus destroyed: "'I want them all gone – hunt them out,' the Tzarina had declared, 'remove them from every nook and cranny they have crawled into in my palace.'" So Katinka escapes, fleeing across the snowy steppe with a 14-year-old giant and a singing dwarf: "A singing dwarf would not be as useful in an escape plan as a tough giant, but there was something in [her] head telling her they should stick together."

What follows is a brilliantly suspenseful novel, which should have even the most reluctant reader eager to reach the next cliff-edge. ("Katinka Dashkova wanted to live, so she held her breath," reads the first sentence, as the heroine hides from a knife-wielding nobleman.) But Scott-Elliot is too poetic a writer ever to let the terror distract from the real adventure – which is the beautifully imagined quest of a child in search of her home.

Order The Tzar's Curious Runaways from the Telegraph Bookshop

Madame Badobedah by Sophie Dahl (Walker) ★★★★☆

Sophie Dahl says one of the greatest gifts her grandfather, Roald Dahl, gave to his family was to make "writing a viable career option". So far, she has put that gift to use by writing a novel, Playing with the Grown-ups (2007), and a cookbook, Miss Dahl's Voluptuous Delights (2010). Now, she has taken the next bold leap in his footsteps by writing a book for children.

Somewhere in between a novella and a picture book, Madame Badobedah tells the story of Mabel, who lives in a seaside hotel. "My dad is the manager, but my mum is the BOSS," Mabel explains – lest anyone look at Lauren O'Hara's delightfully old-fashioned illustrations and think otherwise. Mabel likes adventure, and finds it when the mysterious Madame Badobedah ("rhymes with ooooh la la") comes to stay with 23 bags, two dogs, two cats and a tortoise. After spying through the keyhole, Mabel forms a theory: "She was, without question, an ancient supervillain on the run from the police."

Roald Dahl's fiction has had an incalculable influence – not least on David Walliams, whom many see as his successor. But although Sophie Dahl has spoken of her closeness to her grandfather (he named the "poor little scrumplet" in The BFG after her), she sensibly resists any temptation to imitate his style. There is the odd Dahl-esque touch (Madame Badobedah is "old, old, old. With red lips... her hair was red and crunchy; a toffee without the stickiness") but where Roald's imagination was fired by the grotesque, his granddaughter is drawn to the gently eccentric. "Even he feels the cold in this country, poor darlink," says Madame Badobedah, as she pours tea from a jumper-clad teapot.

"I really hate bitter books, and bitter people," Sophie Dahl has said. There is no bitterness here, and nothing too revolting – but there is plenty of charm.

Order Madame Badobedah from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Deathless Girls by Kiran Millwood Hargrave (Orion) ★★★★★

Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s lyrical novels have made her the darling of children’s literary fiction. The Girl of Ink & Stars (2016), published when she was 26 and nominated for the Carnegie, is now a fixture on school reading lists. For her fourth novel, however, she leaves her primary school fans behind and plunges into the realms of teenage vampire fiction.

The Deathless Girls tells the story of Dracula’s brides, who are mentioned in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel but never individually named, and their origins are left unexplained. In Stoker’s version, they are seductive vampire “sisters” who reside with the Count in his castle in Transylvania, repulsed by sunlight, entrancing men with their beauty and charm.

It takes a bold author to pick up where Stoker left off, but Hargrave confidently claims the narrative for her own. The “brides” in her story are Lil and Kizzy, twin sisters from a band of Transylvanian travellers, who are brutally kidnapped on the eve of their 17th birthday and enslaved in the castle of the cruel Boyar Valcar. Lil initially finds comfort in her mysterious affinity with Mira, her fellow kitchen maid; but when Kizzy disappears – sent as a gift to the Voivode, as feudal lord who demands blood sacrifices from each Boyar – she must set out on a perilous quest to save her.

Hargrave is an entrancing writer, who gets full mileage out of her Gothic milieu. Castle yards are “red with slaughtered pigs”; and behind every mountain lurks a nightmarish villain: “They call him the Dragon, because he razes whole villages that disobey his command. He is an evil man, with a black heart. Some say he’s worse than a man, has no heart at all.” But this is no mere pastiche. Hargrave is a deceptively modern writer, who finally invests Dracula’s beleaguered brides with some feminist clout.

Order The Deathless Girls from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Ups and Downs of the Castle Mice by Michael Bond (Bodley Head) ★★★★★

Michael Bond will always be remembered for his books about a bewildered Peruvian bear who turned up in 1958 on a platform at Paddington, and swiftly became one of the most commercially successful characters in the history of children’s fiction. (Paddington has starred in three films, five television adaptations, a Marks & Spencer Christmas advertisement, and appeared on a first-class stamp.) But this enchanting short story – which is being published two years after Bond’s death – reminds us that there were other strings to the author’s bow.

In what is believed to be Bond’s final creative work, The Ups and Downs of the Castle Mice follows on from The Tale of the Castle Mice (2016), about a family of rodents living inside a doll’s house in a castle belonging to an Earl. After a series of misfortunes in the first story, Mr and Mrs Perk and their 13 children now face a new threat in the form of the castle’s mercenary housekeeper Miss Price, who intends to exploit the mice as a tourist attraction while the Earl is holidaying in India, then run off with her takings. “As the days went by, the bundles of notes grew higher and higher” – but the wicked Miss Price had not reckoned on the ingenuity of Mr Perk, who mobilises his family in a daring plan to bring her down.

As in the Paddington books, there is a clear moral framework. (“The Earl and Countess have always been very kind to us,” Mrs Perk lamented. “I hate to think of that Price woman taking advantage of their trust.”) Bond was 90 when he wrote it, but his humour remains engagingly boyish – a quality expressed in the beautiful illustrations by Emily Sutton. The result is a story that is poignant but never soppy, with an unexpected twist that suggests the nonagenarian Bond’s imagination was taking an increasingly mischievous turn.

Order The Ups and Downs of the Castle Mice from the Telegraph Bookshop

Lori and Max by Catherine O'Flynn (Firefly) ★★★★★

Children’s fiction has lately come under fire for dwelling on domestic misery at the expense of the traditional adventure story. (As the Branford Boase Award judges last year put it, the fashion for “claustrophobic” family dramas has led to “a rather depressing children’s literary landscape”.) In this masterful detective novel by Catherine O’Flynn, however, a narrative of family dysfunction is cleverly interlaced with old-fashioned derring-do.

The heroines are Lori and Max, 10-year-old girls whose backstories strike an operatic note. Max lives above a chicken shop called Rooster Party (“it’s obviously not a party for the roosters”) with her father, who is a gambler, and her mother, who has depression. Max is always hungry (“some days school dinner is the only meal she has”), her clothes are too small and she is constantly moving school.

Lori is an orphan who lives with her grandmother and dreams of becoming a detective. So far, the most exciting mystery she has solved is the whereabouts of Nan’s spectacles. But when Max goes missing after being falsely accused of stealing money that her classmates have raised for charity, Lori is determined to prove her friend’s innocence.

O’Flynn calls herself “a former child detective who failed to ever solve a crime”, yet she plots with the precision of Agatha Christie, turning every unexpected event into an immaculate puzzle, which the attentive reader can piece together as the story romps on. The deceptively simple plot contains meaty themes of friendship and family breakdown, beautifully observed through the eyes of two children on the cusp of adolescence. O’Flynn’s first novel, What Was Lost (2007), won her a Costa Book Award. This is her first book for children, and it has all the makings of another hit.

Order Lori and Max from the Telegraph Bookshop

Chinglish by Sue Cheung (Andersen) ★★★★★

Stories set in Chinese takeaways are thin on the ground – which makes this debut novel by Sue Cheung a rare gem. Written in diary format, the book tells the story of 13-year-old Jo Kwan, the daughter of Chinese immigrants living in the Midlands. The story begins in 1984, when Jo's family move from Hull to Coventry, where her father intends to open a Chinese restaurant. "My life up till now [has been] completely bonkers," she writes. "But I'm hoping that from tomorrow everything will become normal."

On arrival, however, it turns out that the restaurant is in fact a takeaway, and Jo's home is to be a tiny flat upstairs. Her grandparents are frequent visitors, but most of the adults in the family speak no English, and Jo and her siblings speak no Chinese: "In other words, we all have to cobble together... a rubbish language I call 'Chinglish'. It's very awkward."

It is that awkwardness that Cheung encapsulates so well, as Jo's dreams of becoming an artist clash with the reality of life at home. Her father insists on keeping the takeaway open 364 days a year, and when she returns from her first day at school, her parents are too "busy defrosting squid rings" to talk to her.

("'Huh?' [Mum] replied. And that, sadly, is how most of our conversations end.") Cheung says that the book is based on her own childhood – evidenced in the convincing precision with which she recalls every domestic detail – be it her parents "arguing over what was a safe amount of monosodium glutamate to put in the food without poisoning customers"; or the "handcrocheted antimacassar" on her grandmother's armchair.

Writing about her past, she says, has "saved me paying for an expensive course of therapy". It has also resulted in a first-class book.

Order Chinglish from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Time of Green Magic by Hilary McKay (Macmillan) ★★★★★

Hilary McKay has become the Joanna Trollope of children's fiction, belting out sumptuously fleshed, compulsively readable family sagas. Since her debut, The Exiles (1991), about four sisters sent to live with their grandmother, she has written 56 books. Last year, The Skylarks' War, set during the First World War, won the Costa.

Her latest, The Time of Green Magic, is set, like many of McKay's stories, against a background of domestic dysfunction. The heroine is 11-year-old Abi, an only child whose mother died when she was a baby. When the story begins, Abi's father has just remarried, and reading has become Abi's escape from her new stepbrothers. "She read while other people cooked meals and loaded dishwashers and swept floors. She read while her father dragged into her life Polly as stepmother, plus two entirely unwanted brothers." But when the family moves into a new house with "a lantern straight out of Narnia" by the front door, the children find themselves drawn together by mysterious goings-on, to which their parents seem blind. "Abi couldn't yet grasp what she'd seen, except somehow, once again there had been magic in the house." And after Louis wakes to find a strange creature in his room ("whatever it was it growled, so low in its throat that the vibrations ran through the bed like electric pulses"), the children determine to discover where it belongs.

What follows is an inventive and beautifully told story, which should keep any young reader gripped. But the real pleasure of McKay's fiction lies in her eye for the everyday. There is always drama in her books, but she is too confident a writer to feel the need to shatter any teacups – and unusually for a children's author, many of her tales have no obvious villain. As she puts it: "I've met very few villains in my life Most people are extremely nice."

Order The Time of Green Magic from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Girl Who Speaks Bear by Sophie Anderson (Usborne) ★★★★★

I always enjoy the nuggets of biography publishers tell us about their authors. Sophie Anderson, apparently, lives in the Lake District and likes "fell walking and canoeing". But her books are much darker than anything her Girl Guide lifestyle might suggest. Last year, her lyrical debut novel The House with Chicken Legs told the story of a young girl under the spell of the mythical Baba Yaga. Her follow-up, The Girl Who Speaks Bear, also contains strong echoes of Slavic folklore.

This enchanting story is set in a Siberian snow forest, where the 12-year-old heroine Yanka was found standing naked 10 years ago outside a bear cave, and adopted by a local villager. Yanka remembers the bear that nurtured her as a baby, "nuzzling my face into her warm belly.

Huge furry limbs shielding me from the biting snow." As she gets older, her curiosity grows: "I wonder if she remembers me... misses me. I wonder about the bear almost as much as I wonder about my real parents." Yanka has never felt she belongs in her adoptive community ("Everyone else in the village was born here...

They wear fur coats passed down from great-grandfathers") – a sentiment exacerbated when she wakes up one morning to discover that her legs resemble those of a bear: "[They] are enormous... And covered in fur... Like a bear. I have bear legs." Rather than be taken to hospital, Yanka runs away: "I need to find more than a cure for these legs. I need to understand why they have grown... and I think those answers lie in the forest."

Like Anderson's first novel, this is a tale of identity and belonging, but she is too good a storyteller ever to let moral messages slow down the plot. And, like all the best fantasy writers, she manages to invest even her wildest imaginings with the ring of truth.

Order The Girl Who Speaks Bear from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Monster Who Wasn't by TC Shelley (Bloomsbury) ★★★★☆

The monster is the current darling of children's literature, with titles such as There's a Monster in Your Book (Tom Fletcher) and Eat Pete (Michael Rex) encouraging younger readers to see every beast's lovable side. But this new fantasy series by the previously unpublished schoolteacher TC Shelley takes a more old-fashioned approach. "It is a well-known fact that fairies are born from a baby's first laugh," the book begins, citing one of JM Barrie's rules – and monsters, according to Shelley's logic, "are born from a human's last sigh and the vileness of the monster is in direct proportion to the depth of the sigher's regret".

The story begins on "Hatching Day", when the newest human sighs flit down to the monsters' "cavern of filth" beneath the earth's surface and hatch under the watchful eye of the all-powerful King Thunderguts. But to the other monsters' disgust, one of the sighs turns out to have been contaminated by a baby's laugh and hatches into a human boy. ("'Good grief. It looks human,' something hissed.") The child, known as Imp, is saved when he is adopted by a family of gargoyles who claim him as one of their own: "Goblins come in all shapes and weirdnesses. It's part of our charm. Don't you worry, you're just the same as the rest of us." But when King Thunderguts involves Imp in a plot to make monsters the masters of the world, the child's future looks increasingly precarious.

Shelley is a first-time novelist who writes with the confidence of an old hand. The plot never flags, but characters have time to develop, and even Shelley's most outlandish creations are rendered believable by her descriptive precision. August is a quiet month in children's publishing, which makes this wonderful debut all the more of a treat.

Order The Monster Who Wasn't from the Telegraph Bookshop

Crossfire by Malorie Blackman (Penguin) ★★★☆☆

When she was appointed Children's Laureate in 2013, Malorie Blackman suggested that black characters put parents off buying books: "Children will go with any story as long as it's good but white adults sometimes think that if a black child's on the cover it is perhaps not for them," she said. Blackman has been overturning such prejudice with her own book sales. She has published more than 60 titles, most famously her Noughts and Crosses series, which was inspired by her anger at the death of Stephen Lawrence, and ranks among the bestselling YA fiction of recent years.

Crossfire is the fifth in the series and, like its predecessors, set in a dystopian future in which the all-powerful black Crosses preside over an underclass of white Noughts. The first book told the story of the doomed love affair between 17-year-old Sephy, the daughter of a black politician, and Callum, a young Nought involved in terrorism. Crossfire takes up the story more than 30 years on, but the plot is still boiling briskly, with the country's first elected Nought Prime Minister accused of murder, and two new teenage protagonists Troy and Libby embroiled in a whirlwind kidnap.

Blackman says that all her books are written in response to current events, and here she alludes to both Brexit and Donald Trump. Her plots are always densely woven, and those who have missed any of the earlier instalments will find some of the threads hard to untangle, but she is a supremely suspenseful writer, who will soon lull you into ditching the crib sheet and letting the story sweep you on.

Some of her fans might feel let down by the ending. After 464 pages, it feels a little unsporting to leave us dangling from a cliff in the final chapter, which ends with several aspects of this nail-biting drama unresolved.

Order Crossfire from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Curse of the School Rabbit by Judith Kerr (HarperCollins) ★★★★★

When Judith Kerr died in May, aged 95, she left a legacy of more than 30 books, which had established her as one of the greatest children's writers of her age. Her most famous title, The Tiger Who Came to Tea, was published half a century ago. But The Curse of the School Rabbit – which she was working on in the final months of her life – bears all the hallmarks of Kerr in her prime.

The story is narrated by Tommy, whose father is an out-of-work actor ("Dad had been having one of these 'resting' patches for a while, and I was getting a bit worried because it was coming up to Christmas and I really need a new bicycle"). When the family is co-opted into looking after the school rabbit Snowflake, Tommy's little sister Angie is delighted. But Tommy has misgivings, which appear to be borne out when Snowflake pees on the trouser leg of a film star who comes for dinner, thereby dashing his father's hopes of a job. When Angie then falls ill, Tommy becomes convinced that Snowflake has placed a curse on the family. ("I went to feed Snowflake, and I said, 'It's all your fault, you stupid rabbit!'") But when Snowflake goes missing, Tommy takes charge ("I thought, I must find that rabbit"), and in a seamless narrative twist, the mischievous pet finally brings the family some good luck.

Kerr's work ranges from When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (1971), a semi-autobiographical novel about a Jewish family fleeing Nazi Germany, to her ever-popular picture books about Mog the cat. This latest story possesses all of her trademark qualities: lyrical artwork, a gently anarchic plot and the warmth and humanity that made her work immune to shifts in publishing fashion. And perhaps what is most impressive in an author of 95: the unfailing ability to see the world through the eyes of a child.

Order The Curse of the School Rabbit from the Telegraph Bookshop

Alfie on Holiday by Shirley Hughes (Red Fox) ★★★★☆

The seaside has inspired some of our most gluttonously nostalgic picture books – from The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch, still in print more than 40 years after its publication, to contemporary (but equally old-fashioned) titles such as Nicola Davies’s wonderful A First Book of the Sea (2018). And when the author is our 92-year-old national treasure Shirley Hughes, we can expect the nostalgia gauge to read even higher than usual.

Such is the case with Alfie on Holiday, the 23rd book in the Alfie series, which features Hughes’s four-year-old hero on its cover, standing in front of a sandcastle. It is now more than 30 years since the first Alfie book – but little has changed. There are no iPads or mobile phones, and no concessions to the vagaries of style. Alfie is still wearing leather sandals, and his little sister Annie Rose is still tumbling about their cluttered home, placing rival demands on their stay-at-home mother.

Annie Rose “was not feeling well” the story begins, in a flourish of Hughesian drama. “She was awake a lot in the night and kept crying. Mum was very busy looking after her.” Alfie is bored – but Grandma comes to the rescue and takes him to the sea.

Hughes’s simple words and familiar drawings capture the timeless excitement of a seaside holiday, as Alfie and his grandmother run “down across the pebbles to the big sandy beach”. But in Hughes’s stories a conflict is always rumbling. And here, in a drama to which every preschool child will relate, Alfie makes a new friend, who ignores him the next day when more interesting companions arrive. Hughes never moralises. But lessons are gently learnt – and soon Alfie is home, making dens with his “truly special friend” Bernard. This is an enchanting book in which Hughes weaves her magic as deftly as ever.

Order Alfie on Holiday from the Telegraph Bookshop

Anna at War by Helen Peters (Nosy Crow) ★★★★★

The Second World War has inspired so many of the most cherished children’s novels of the past half-century – from Goodnight Mister Tom to Carrie’s War – that new historical fiction can struggle to make its mark. Even in such august company, Anna at War – told from the perspective of a modern 10-year-old boy and his 89-year-old Jewish grandmother – is a welcome addition to the canon.

Daniel knows little about his grandmother’s history: “I knew she left Germany to get away from Hitler, but anyone would want to get away from Hitler, wouldn’t they?” When he learns more about the war at school, his curiosity is aroused – and his grandmother finally tells him the story of her childhood. Anna begins with her memories of Kristallnacht, when her family lived in a small German town, in which her father ran a publishing company: “[I] peeped through the narrow gap between the wardrobe doors… Two Nazi stormtroopers were destroying my room. One man stabbed through my bedclothes with a bayonet… Would he have done that if I had still been in the bed?” That night, Anna’s father is taken to Buchenwald (“I had heard of concentration camps. They were prisons for people the Nazis didn’t like.”) Anna escapes to England on the Kindertransport, and is placed in the care of a farming family in Kent. But from this place of apparent safety, she swiftly stumbles into a web of rural espionage, and finds herself embroiled in a perilous intrigue involving an injured German spy.

Helen Peters dedicates her book to “all the children who have had to leave their homes and make new lives in other places”. But despite its meaty themes, this is first and foremost a fast-paced adventure, whose elegant prose and cliffhanger chapters should keep even less confident readers gripped to the thrilling end.

Order Anna at War from the Telegraph Bookshop

Jemima Small Versus the Universe by Tamsin Winter (Usborne) ★★★★★

Fat children have fared badly in fiction. At best, characters such as the slothful Billy Bunter have offered comic relief; while in Lord of the Flies, the asthmatic Piggy is tormented by his peers – and eventually killed. So what a delight to stumble on Jemima Small, a big “whale” of a girl in whom we find the makings of a thoroughly modern heroine.

When the novel begins, Jemima is 12 and lives with her father and her brother, her mother having abandoned the family six years ago. Jemima is fat: “I’m going to tell you the word that ruins my entire life: BIG. Because my name is Jemima Small. But I am exactly the opposite.” At school, she is relentlessly bullied, made worse when she is picked to join a club for overweight pupils: “The words ‘FAT CLUB!’ came hurtling at me across the playground… It’s not just the pain of it. The pain you get used to. It’s the embarrassment.”

Jemima wants only to be thin, and to have her mother back. But in Tamsin Winter’s novels there is never a quick fix: “No matter how much wishing I did, my body stayed the same shape, and my mum didn’t reappear.”

Winter does not spare the reader’s heartstrings. Her debut, Being Miss Nobody, is about a schoolgirl who suffers from selective mutism, and whose brother is dying of leukaemia. But here, as then, the joy in the story lies in the way the odds are overturned, and the heroine’s true identity emerges. Winter beautifully captures Jemima’s voice, with its mix of pathos and determination – and the occasional scrap of pithy wisdom thrown in: “It’s like when you look up at the night sky – what you see isn’t the whole picture.”

Winter dedicates the book “to everyone who has looked in the mirror and felt like nothing” – a sentiment to which all too many young readers will relate.

Order Jemima Small Versus the Universe from the Telegraph Bookshop

New Class at Malory Towers by various authors (Hodder) ★★★★☆

Few children’s authors have attracted as much opprobrium as Enid Blyton, who has never been forgiven for inventing a Toyland in which golliwogs stole cars. Yet Blyton has stormed into the 21st century with book sales of 11 million a year – and it is Malory Towers that is coming out tops. A musical version opens in Bristol this month, a television series is in production – and here are four new short stories, each written by an avowed Blyton fan.

It has been more than 60 years since Darrell Rivers and her friends made their final farewell to Potty and Miss Grayling, and in New Class at Malory Towers – which keeps to Blyton’s Forties setting – subtle changes are afoot. A story by Patricia Lawrence brings the first black girl to the school. Another tale stars a girl from India. (“India!” a third-former gasps.) Otherwise, everything is much the same. In a story by Lucy Mangan, we find the familiar cast gathered in the pool (“it was always a joy to bathe in the big hollowed out rock pool down by the sea”), tormenting Gwendoline: “Deep breath, Gwendoline!’ [Darrell] shouted, then ducked her under the water. Alicia shrieked in delight.”

It is easy to parody Blyton, but here each writer resists the temptation, recapturing Blyton’s childlike fluency instead. And in true Blyton style, there are plenty of mysteries to solve – as when Darrell stumbles on sabotage in the school library: “Someone’s vandalised a cookery book with bread and jam.” But alas, the publisher’s stated intention to bring the series “up to date” appears to have been lost on dear old Gwen, who has grown notably snobbier: “‘Oh, you know very well!’ Gwen clearly wasn’t about to back down. ‘My mother married up and your mother married down and that is why I am who I am and you are, well’ – she gestured at Maggie – ‘you.’”

Order New Class at Malory Towers from the Telegraph Bookshop

Return to Wonderland by various authors (Macmillan) ★★★★☆

It takes a bold author to rewrite the classics of children’s literature – but there has been no shortage of volunteers. In the last year, there have been retellings of everything from Malory Towers to The Jungle Book, while Michael Morpurgo (who has already retold Peter and the Wolf and The Wizard of Oz) released a novelised version of The Snowman. But one does not mess lightly with Lewis Carroll (an author described as “the Tolstoy of the nursery”), which is perhaps why 11 children’s authors have clubbed together for the task of reimagining Wonderland more than 150 years after Alice left.

Each contribution takes the form of a separate story, based on one of Wonderland’s inhabitants. But while the cast is familiar, some of the scene changes might leave Carroll flummoxed. In a story by Pamela Butchart, Alice has told “LOADS of people EXACTLY where the rabbit hole was”, with the result that “EVERYONE” has started “abseiling down [it] for their holidays”. Wonderland is now “SO POPULAR” that Disneyland in California “AND the one in Paris” have gone into administration.

Lisa Thompson makes an engagingly unreliable narrator out of the Knave of Hearts, whose story she feels Carroll left incomplete: “He stands accused of stealing the Queen’s jam tarts” but “we never hear the final verdict”. And Piers Torday solves the mystery of how the Cheshire Cat got his smile. There is a feast of invention and fine writing here – as one would expect from a list that includes star names such as Lauren St John and Robin Stevens. But as with any retelling, one has to ask what purpose it serves. And the publisher’s promise to bring “a whole new generation of readers to Wonderland” perhaps misses the point that the years have never withered Wonderland’s charm.

Order Return to Wonderland from the Telegraph Bookshop

Noel Streatfeild’s Holiday Stories by Noel Streatfeild (Virago) ★★★★★

Noel Streatfeild wrote more than 80 books, including her beloved children’s novel, Ballet Shoes. But she is the fount that keeps on flowing – and here is a brand new collection of stories, published more than 30 years after her death. These 14 stories, which were written between the Thirties and Seventies, were recently found buried among Streatfeild’s papers. As one might guess from their dreamily nostalgic titles (“Chicken for Supper”, “Let’s Go Coaching”), there are few pantomime twists or cliffhanger endings. Instead, their charm lies in their evocation of the small, everyday dramas of childhood.

In one story, two children go to stay with their grandmother in Devon and meet a mysterious stranger while picking whortleberries on the moor. In another, four circus children find themselves camping near the home of their “very, very grand and very, very proper” cousins, the Flags. In a Streatfeild story the moral is always clear, even if the social mores might leave the modern young reader somewhat baffled: “Although Duke Flag had made his money in a chain of grocery stores there was not one in the refined neighbourhood in which he lived, so he was just accepted as a pillar of society. He lived in a pillar-of-society house, which was modern Tudor, with a hint of Norman castle.”

In an intriguing author’s note, Streatfeild explains how her own childhood feelings of inadequacy (she describes herself as “downright plain” and “a slow developer”) inspired her to become a writer. “Being an unsuccessful child,” she writes, “makes you look very carefully, with almost grown-up eyes, at yourself and the people around you.” It is that ability to “look very carefully” that makes these languid little stories such a rewarding read.

Order Noel Streatfeild's Holiday Stories from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Garden of Lost Secrets by AM Howell (Usborne) ★★★★★

While the Second World War has inspired some of the most famous children's novels of the past half-century (Carrie's War, The Silver Sword, Goodnight Mister Tom), the First World War has produced considerably fewer. But the centenary of the Armistice has altered the balance, with titles such as The Skylarks' War (Hilary McKay) among a stream of prize-winning new fiction set during the Great War. The Garden of Lost Secrets is another such gem.

The story begins in October 1916, when 12-year-old Clara is sent to stay with her aunt and uncle, who work as the housekeeper and head gardener on a country estate. "Try not to worry, Clara ... Look on this as a little adventure. We will all be together again soon," her mother reassures her. But on arrival, Clara finds her aunt and uncle unrecognisable from the jocular figures she remembers from earlier visits. Among her aunt's litany of rules is that Clara is "under no circumstances ... to go near the Earl's hothouses or summer house". But naturally, she does, and soon finds herself embroiled in a deftly plotted mystery involving a locked room, a ghostlike child who appears in the gardens at night – and the disappearance of the Earl's coveted pineapples. Clara, writes Howell, "had never thought of herself as particularly brave". But as her "little adventure" spirals into a perilous quest for truth, this young heroine shows herself a match for any 21st-century schoolgirl sleuth.

Debut writer Howell says her story was inspired by reading an old gardener's notebook from Ickworth House in Suffolk – and she writes with the ease of someone who feels thoroughly at home in her historic milieu. But this is also a touching story about courage and friendship, which should appeal equally to readers with more modern tastes.

Order The Skylarks' War from the Telegraph Bookshop

Evie and the Animals by Matt Haig (Canongate) ★★★★★

Matt Haig's bestselling memoirs Reasons to Stay Alive (2015) and Notes on a Nervous Planet (2018) explored his struggle with depression, and made him one of the most popular self-help writers in the world. His children's fiction seems far removed from his adult titles, in which he remembers a youth shadowed by the fear of "death or total madness". But Haig says that all his stories are "really guide books", in which he shares the lessons learnt during his recovery. His first picture book, The Truth Pixie (2018), concerned a girl who is worried about the future. Haig described it as: "Reasons to Stay Alive for seven-year-olds – but with trolls and elves and silly jokes thrown in."

In that title, the theme was anxiety. In Evie and the Animals, we have scrolled down the self-help index to find ourselves at "fitting in": "Once there was a girl called Evie Trench. Evie was not a normal child. She was a 'special' child ... Evie often thought it would be a lot easier to be a normal child than a special child, but there you go."

Haig is too accomplished a storyteller to allow lessons to be overstated, and what follows is a suspenseful thriller, with a fine balance of peril and poignancy. Evie can talk to animals, and it is through her conversations with characters such as Beak the sparrow that Haig dispenses some of the pithy wisdom that characterises his adult books: "If you have wings. It's like freedom... There is nothing like being free to be yourself." But things take a sinister turn when Evie finds herself under threat from the villainous Mortimer, who "uses animals to kill everyone with the Talent. This is why you must never act on it again." Haig is a deeply engaging writer. This book will appeal to a wide range of readers – not just those who worry about fitting in.

Order Evie and the Animals from the Telegraph Bookshop

Rumblestar by Abi Elphinstone (Simon & Schuster) ★★★★★

Abi Elphinstone has been described as a "worthy successor to C S Lewis" and her fantasy novels (The Dreamsnatcher, Sky Song) have been compared to Narnia. This seems a heavy burden to place on her, given that Lewis was one of the most influential writers of the last century, who became – in the words of the American magazine Christianity Today – "the Aquinas, the Augustine and the Aesop of contemporary evangelicalism".

If you read Elphinstone's latest novel Rumblestar seeking theological wisdom, you will be disappointed. But this is a suspenseful and beautifully imagined fantasy that will have a new generation of followers. The book's unlikely hero is the 11-year-old Casper Tock, a bursary boy at Little Wallops boarding school. Rich children make easy villains in children's fiction, and Casper's odious classmate Candida is one such caricature: "You don't belong here... The pupils at Little Wallops are from well-connected families. We're refined. Special." Casper keeps a low profile and adheres to a rigid regime ("that way, fewer things went wrong"). But one day he stumbles into Rumblestar, an Unmapped Kingdom whose magic is under threat from the evil harpy Morg. Casper must rise to the rescue, aided by his new friend Utterly Thankless, a girl allergic to behaving, and her miniature dragon Arlo.

Elphinstone is a joyful writer who never lets the action flag. Her jaunty style is a far cry from the stark beauty of Lewis's prose. But as in all good fantasy, there is a deeper meaning, and the real magic in her story lies in the transformation of an ordinary child: "Back in Little Wallops he would have let people walk all over him [but] out here in the forest he felt suddenly bold. 'I'm a million miles from home, Utterly, but I'm giving this quest everything I've got.'"

Order Rumblestar from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Good Thieves by Katherine Rundell (Bloomsbury) ★★★★★

Katherine Rundell's first four novels had ecstatic reviews ("The world had better watch out!" raved Philip Pullman about The Wolf Wilder) and made her the queen of highbrow children's fiction. She has said that her aim when she writes is "to put down ... the things that I most urgently and desperately want children to know." This sense of urgency informs her latest novel, The Good Thieves, which combines a galloping plot with some neatly scattered pearls of wisdom.

The story is set in Thirties New York, where Vita Marlowe's grandfather has been robbed of his family home by a notorious con man. So Vita and her mother set sail from their home in England to put things right. Rundell's heroes seldom have it easy. (In The Explorer, four young children have to battle through the Amazon jungle; in Rooftoppers, the infant Sophie is found floating at sea in a cello case.) But despite suffering from ongoing pain as a result of polio, Vita faces every challenge with Rundellian fortitude. When we meet her she is standing on deck as her ship crests a wave "the size of an opera house"; and she arrives in New York with the bombast of a young Donald Trump: "Vita set her jaw and nodded at the city in greeting, as a boxer greets an opponent before a fight." But when she finally tracks down the con man, Vita's quest for justice takes an unexpectedly perilous course.

As a child, Rundell has said, she read "with a rage to understand". There are moments in her writing when life's lessons can seem too eagerly applied ("Love has a way of leaving people no choice"; "It is not always sensible to be sensible", etc). But this is a nit-picking criticism. The Good Thieves is another suspenseful and beautifully written book that will delight Rundell's fans.

Order The Good Thieves from the Telegraph Bookshop

We Won an Island by Charlotte Lo (Nosy Crow) ★★★★★

Twenty-five years after his death, ITV’s sun-soaked adaptation of Gerald Durrell’s Corfu memoirs has catapulted his books back into the bestseller lists. With Durrell-mania at an all-time high, will this debut novel by Charlotte Lo – “about island life with hints of The Durrells” – stand up to its tantalising sales pitch?

The heroine is Luna, one of three children whose bereaved father has been suffering from depression: “Everything changed when [Granny] died. Dad barely spoke any more. Instead he just spent all day asleep or watching old Countdown episodes.” He has stopped going to work, and when the story begins the family is facing eviction from their London flat. But an escape is offered when a billionaire launches a competition to give away his remote Scottish island, and Luna unexpectedly wins: “I missed Dad’s smile. If he just gave the island a chance, I was sure he’d find it again.” So Luna’s bewildered family duly find themselves pulling their suitcases across an abandoned beach, and moving into a tumbledown house full of bats. “Vines climbed up the brickwork, twisted around the windows and swallowed the front door… our island was a tangle of weeds, colourful flowers and zippy insects.”

What follows is a touching story of domestic mayhem and the restorative power of nature. Lo is a simple, elegant writer, whose prose will appeal to readers of all ages. But while there is plenty of comedy (not least when Luna’s brother enters a local sheep pageant), at the heart of the tale is Luna’s struggle to win her grieving father back. Most children’s books contain some sort of baddie. But here there are no villains, and even the billionaire turns out to be benevolent. It might not be Corfu, but this book is definitely a bask in the sun.

Order We Won an Island from the Telegraph Bookshop

Malamander by Thomas Taylor (Walker) ★★★★★

Thomas Taylor's career as a children's illustrator took off like a meteor 20 years ago, when he drew the cover for the first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. Since then, he has written and illustrated umpteen picture books but only now has he finally published a fantasy novel of his own.

Malamander tells the story of 12-year-old Herbert Lemon, who lives and works in the Lost and Found cupboard of the Grand Nautilus Hotel in Eerie-on-Sea, returning mislaid goods to their owners. In summer, the town is filled with day-trippers and ice-cream vans. But in the winter, "when sea mist drifts up the streets like vast ghostly tentacles, and saltwater spray rattles the windows", the promenades empty, and everyone fears the legendary sea monster: "when darkness falls and the wind howls around Maws Rock... some swear they have seen the unctuous malamander creep."

One such winter, young Violet Parma appears at the hotel, and asks Herbert to help track down her parents, who vanished when she was a baby. "I think you are the only person in the world who can help me... Because I'm lost... And I'd like to be found." When the children discover that the Parmas' disappearance is linked to the dread malamander, their investigation takes a sinister turn.

Taylor is a supremely elegant writer, who does not dilly-dally. The plot is delivered like gunfire, and even less confident readers will be encouraged by cliffhanger chapters and knuckle-whitening prose. But this is also a touching story of friendship and loss, with wonderful vignettes of children on the cusp of growing up. Children's fantasy has become a crowded landscape in which new novelists can vanish without trace, but Taylor stands out. This is a sumptuously imagined book, which works a powerful spell.

Order Malamander from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Umbrella Mouse by Anna Fargher (Macmillan) ★★★★★

Animals are popular heroes of children’s fiction set in the First or Second World War. While tales of canine or equine bravery abound, this enchanting first novel by Anna Fargher shows us warfare from the often overlooked perspective of an urban mouse. The story begins in 1944, in James Smith & Sons, an umbrella shop in Bloomsbury, where the young Pip Hanway lives with her parents. Countless generations of Hanway mice have made their nest inside the same ancient umbrella (“You live in a piece of history!” as Pip’s father reminds her); and Pip has little experience of the world outside.

Then, one day, a bomb strikes the shop, killing both her parents: “The grandfather clock clunked mechanically… It was just before it finished playing the Westminster Chimes that it happened. As if from nowhere, a terrible crash thundered through the shop, and nothing was ever the same again.” So Pip sets off for northern Italy to find the umbrella museum where her mother lived as a girl, before stowing away to England in a parasol. “I know where I’m meant to go! … I’m going to the umbrella museum in Gignese.”

Mice are often sentimentalised in children’s fiction, but Fargher invests Pip with the complexity of a human while still minutely observing her every rodent characteristic. Pip’s adventure brings her into the company of other displaced animals, all of whom are rendered similarly plausible. Particularly engaging is the loquacious rescue dog Dickin, who relishes telling us what is going on: “These new V-1 rockets are Hitler’s vengeance weapons. Now that we have a foothold in France, the Allies have a chance of crossing the continent and closin’ in on Germany and he’s as mad as a hatter about it.” This beautifully written book is aimed at nine-year-olds, but will appeal to much older children, too.

Order The Umbrella Mouse from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Secret Starling by Judith Eagle (Faber) ★★★★★

According to the judges of the Branford Boase Award for children’s fiction, today’s novelists are spurning adventure stories in favour of “claustrophobic” domestic dramas, and creating a “depressing children’s literary landscape”. And yet the success of writers such as Robin Stevens (Murder Most Unladylike) and Katherine Rundell (The Explorer) suggests that the old-fashioned adventure story is enjoying a renaissance – and The Secret Starling by debut novelist Judith Eagle is a fine example.

The story is set in the Seventies, and the heroine is Clara, who lives at wind-ravaged Braithwaite Manor with her “icily cold” uncle, “who didn’t have a fun bone in his body… not a glimmer of warmth radiated from this sternest of beings. It is entirely possible that he had no real feelings at all.”

The house is equally forboding: It “look[ed] like something out of a Victorian gothic novel, crouching in the middle of the moors like an angry crow. A single dark turret rose up to stab the gloomy skies.” Clara’s governesses have all fled in terror (“‘It’s like life GROUND to a halt in the 19th century!’ the last-but-one had cried, grabbing her bag”), and Clara lives a life of unremitting tedium. But the adventure begins when her uncle disappears, sacking the cook and the butler, leaving Clara with £200 to fend for herself.

Eagle is a thrilling writer, who turns this pantomime-gothic set-up into a highly suspenseful modern tale, in which Clara and her new friend Peter battle for survival and unravel a web of grown-up deceit. Eagle’s prose is sparse, and the deceptively complex plot unravels at cracking pace. But she is no Enid Blyton – for the real pleasure in this story lies in the transformative friendship between Clara and Peter, whose adventures should appeal to boys and girls alike.

Order The Secret Starling from the Telegraph Bookshop

Dear Ally, How Do I Write a Book? by Ally Carter (Orchard) ★★★★☆

It takes a bold novelist to tell her fans how to write a book. But Ally Carter has cause to be confident. As she muses in the introduction to this highly entertaining how-to manual for budding writers: “Surely, after 10 years in this business and with a total of 15 books under my belt, I should know what I’m doing by now.”

Carter’s enticingly titled novels (I’d Tell You I Love You, But Then I’d Have to Kill You; Only the Good Spy Young) have made her one of the global queens of teenage drama – and experience has taught her that fiction is not an exact science: “I can’t really tell you how to write a book. There is no single way to do it, you see. Every author is different. Heck, every book is different.” So she sets out to cover the rudimentary skills, such as plotting and characterisation.

But what one marvels at is Carter’s aptitude for drama. “Writing takes time. It takes work. It takes putting in the hours – sometimes more than a thousand of them,” she tells us breathlessly, adding that she spends “at least 900 hours” on each book, 30 of them taken up crying.

There are also lessons in metaphor: “You see, in a lot of ways, writing is like turning on a garden hose that hasn’t been used in a really long time. The first water out of the hose is always rusty and dirty… But it doesn’t stay that way. Nope. The longer the water runs, the clearer it will be.”

The water flowing from Carter’s hose sometimes looks rather transparent. (“The great thing about writers is that most of them are really, really nice” is not a sentence one might expect from someone teaching us about characterisation.) But this book is not aimed at the next Doris Lessing. It is aimed at the next Ally Carter – and for anyone wanting to write like she does, it is a masterclass not to be missed.

Order Dear Ally, How Do I Write a Book? from the Telegraph Bookshop

Diary of an Awesome Friendly Kid by Jeff Kinney (Puffin) ★★★★★

The American author Jeff Kinney says that he intended his Diary of a Wimpy Kid books to be nostalgic recollections of childhood, which would appeal more to adult readers than to children. But the charm of this phenomenally successful series (its 13 books have sold more than 200 million copies) has always been best appreciated by the under-12s. The fictional author of the diaries is Greg, a gauche video-game fanatic who endears himself by dint of his childishly anarchic perspective.

But in Diary of an Awesome Friendly Kid, the narrative torch passes to Greg’s best friend Rowley. “My book isn’t about HIM, it’s about ME,” Rowley explains. And what “REALLY gets on Greg’s nerves is when I copy him. So I’m probably not gonna let him know about this journal.” When Greg inevitably finds out he goes “MAD” and insists that Rowley’s diary becomes Greg’s biography. So the rest of the book is a record of Greg’s boasts (“Greg says he only uses five per cent of his brain and if he WANTED to he could levitate a building with his mind”), and of his slapstick antics: “Greg was banned from MY house because he… put cling film over our toilet bowl.”

As with the previous Wimpy Kid books, the story is propelled along by Kinney’s comic strip illustrations, with much of the dialogue expressed in explosive speech bubbles (“GAAAAH!”) – a format particularly suited to reluctant readers. But despite their easy format, the books contain meaty themes to do with family and friendship – and by the end of this nail-biting instalment, Johnson and his Boswell have spectacularly fallen out: “[Greg] said I need to go back through the book and take out all the stuff with me in it… I was pretty mad and I whapped him with his own biography.” More please.

Order Diary of an Awesome Friendly Kid from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Year I Didn't Eat by Samuel Pollen (Yellow Jacket) ★★★★★

Samuel Pollen's novel comes with a warning: "This is a book about anorexia. It includes calorie numbers and descriptions of disordered eating. Please read and share carefully." It is perhaps not the greatest sales pitch. But this is a clever and touching novel, in which anorexia looms over the narrative like the monster in a horror show.

The story is narrated by 14-year-old Max, who records his struggle with an eating disorder in a diary that he is advised to keep by his therapist. Pollen himself developed anorexia when he was 12, and has likened the illness to having a "bad cop" inside your head. It is that bad cop, Ana, to whom Max's diary is addressed. She is his illness personified, and the only person in whom he can confide: "There are seven billion people on this planet, and somehow, the only person I can actually talk to is you."

As the illness consumes him, Max grows more isolated, avoiding people who "don't know what I'm like now". To Ana, he tells everything ("I didn't eat any food all day, then drank two pints of water..."). As he fades away, his monstrous alter ego grows ever stronger, greedily fuelling his phobias. "Do you really need to eat that? ... You'll look like a sumo wrestler if you eat one of those." Max has flashes of rebellion – "What I need to do is kick you out of my head for good" – but Ana always bounces back: "Do you reckon your mum and dad got special scales to trick you into eating more?"

It is through this torturous dialogue between Max and Ana that Pollen lets us see what anorexia is like. Some young readers might find the subject matter heavy going, but the teenage narrator is brilliantly authentic – and the message is a hopeful one. "Someone doesn't need to understand you to save your life," Max finally observes. "They just need to care."

Order The Year I Didn't Eat from the Telegraph Bookshop

Horrid Henry: Up, Up and Away (Orion) ★★★★★

Francesca Simon has described her fictional hero Horrid Henry as “an embodiment of that impulse in all of us – to rule the world and get our own way”.

Henry does not always get his own way, but he might reasonably be feeling rather pleased with himself. For he has now starred in 25 books, which have sold 20 million copies, making him one of the most profitable rascals in children’s fiction.

We were supposed to have seen the back of him in 2015, when Simon announced that Horrid Henry’s Cannibal Curse was to be his final appearance. But lo – here he is again, in a new book to celebrate the series’ 25th birthday. Up, Up and Away contains four new stories, each featuring Henry in reliably rebellious mood. In one, he runs wild on an aeroplane (“WAAAAHHHH! Horrid Henry could stand it no longer. He’d go mad if he stayed in this HELLHOLE.”); in another he attempts to write an essay on the Tudors (“Who cared how many wives KING GREEDY GUTS had?”).

In the hands of Enid Blyton, such stories would read like cautionary tales. But Henry is impish rather than malicious. And Simon’s great skill is to make him lovable, by seeing the world entirely through his comically anarchic perspective: “No playtime? That was a FATE WORSE THAN DEATH.”

After a quarter of a century, Henry’s battles have a cozy familiarity. Simon is particularly good on his sibling rivalry with Perfect Peter, his smug younger brother, and on his impassioned dislike for his schoolteacher Miss Battle-Axe, an “ALIEN SLIME MONSTER” with “bulging red eyes” and “FIRE escaping from her nostrils”. But not even the most ferocious grown-up can make any impact on Henry’s behaviour. In 25 years, he has learned no lessons at all – which accounts for much of his appeal.

Order Horrid Henry: Up, Up and Away from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Boy Who Flew by Fleur Hitchcock (Nosy Crow) ★★★★★

That children have a hearty appetite for murder has been proved by the success of authors such as Robin Stevens, whose Murder Most Unladylike series features two schoolgirl detectives, forever stumbling upon dead bodies. Fleur Hitchcock’s writing, on the other hand, really isn’t for the faint-hearted. Murder at Twilight told the terrifying story of a vanished schoolboy; in Murder in Midwinter, a child is forced into hiding after witnessing an argument linked to a killing.

Hitchcock’s readers expect a white-knuckle ride, and her latest novel – set in 19th-century Bath and filled with Gothic skylines and dastardly villains – will not disappoint. The hero is Athan, who lives in Dickensian poverty with his mother and two sisters. To help the family survive, Athan works for Mr Chen, an inventor who appeared in his life “like a kingfisher on a wet day”, and has become his mentor: “No one’s ever managed to teach me anything before, but Mr Chen’s different. It’s as if he knows everything – the why of everything, the truth.” When Mr Chen is murdered, Athan determines to prevent the details of their latest invention – a flying machine – from falling into enemy hands. But as he sets out to track down Mr Chen’s killers and protect their secret, Athan finds his family in growing peril.

Hitchcock says that this story has been 10 years in the making, with more than 30 abandoned drafts, but you never sense this struggle in her writing. The book is aimed at readers of nine plus, even the more reluctant of whom will be swept along by the cliffhanger chapters and simple, suspenseful prose. It is a far cry from Pippi Longstocking. “This morning, Haddock the auctioneer was found viciously harmed unto death. His damaged corpse was left hanging from Mr Wood’s new crescent. His tongue…”

Order The Boy Who Flew from the Telegraph Bookshop

Your Mind is Like the Sky by Bronwen Ballard (Frances Lincoln) ★★★★☆

Our most cherished picture books tend to be those that contain an underlying wisdom. Giraffes Can’t Dance (Giles Andreae) affirms that it is all right to be different; Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar has inspired Marxist, feminist and queer interpretations – but is described by its author as “a book of hope”, showing how even the most insignificant-seeming creature can unfold its talent. But our busy modern children do not need whimsical stories to help them make sense of the world. Instead, they can take direct advice from a growing library of self-help books, designed (to quote the author of one, Create Your Own Happy) to help them take “positive steps towards their own happiness and positive self-esteem!”

Some parents might find the idea of children’s self-help off-putting. But Your Mind is Like the Sky, by Bronwen Ballard (a “personal coach and organisational consultant”), is an exemplar of the genre. It is aimed at readers of seven, but would be suitable for younger ones too. “Your mind is like the sky,” it begins. “Sometimes it’s clear and blue”, with “white, fluffy cloud thoughts”, but sometimes it is full of “darker, meaner, raincloud thoughts”. This is the problem that the book addresses.

Most children’s self-help books take anxiety as their theme. Unusually, however, there are no games or activities suggested here, and no “calm down tactics”. The message is relayed solely through the pictures and text, which show a little girl wrestling with her dark thoughts – and finally beating them. “When a raincloud thought comes into your head, you say, ‘Oh, it’s a raincloud thought’”. And then you notice all the white fluffy cloud thoughts as well.” With lyrical illustrations by Laura Carlin, this is an engaging and refreshingly jargon-free book, which would be ideal for any worried child.

Order Your Mind is Like the Sky from the Telegraph Bookshop

Enchantée by Gita Trelease (Macmillan) ★★★★★

There is something about the title Enchantée that raises suspicion. Is it chick lit? Is it a vocab book? Is it a French etiquette manual? But quelle surprise! It turns out to be a densely plotted historical fantasy by Gita Trelease – a debut novelist who is being excitedly compared to Victor Hugo.

The story begins in Paris in 1789, on the eve of the French Revolution, when the 17-year-old Camille has been left destitute after the death of her parents from smallpox. As well as providing for her younger sister, Camille must cope with an abusive older brother who squanders their rent money gambling with the Duc d’Orléans.

To survive, Camille has been reluctantly practising the magic skills taught by her mother, enabling her to turn scraps of metal into coins: “These days, her hands never stopped shaking… Little by little, magic was erasing her. Sometimes she felt it might kill her.” But hunger drives her ever further, until eventually she transforms herself into the dazzling Baroness de la Fontaine, and leaves her freezing garret for the Palace of Versailles and its decadent webs of aristocratic intrigue.

In lesser hands, this might all sound like a Disney cartoon treatment. But Trelease is a supremely confident writer who gives even the most outlandish fantasy the ring of truth. History lessons are swiftly dispensed (“Everyone’s struggling these days… We’re not the only ones. Apart from the nobles, all the people of France are hungry”); but every gilded carriage and lead sky is recorded with cinematic precision.

This book may be a far cry from Les Misérables, but it is a triumph of high jinx over history, which should keep young readers enthralled to the meticulously plotted end.

Order Enchantée from the Telegraph Bookshop

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Sabina Radeva (Puffin) ★★★★★

It is always satisfying to find a children’s book that fills in some of the guilty gaps in a parent’s knowledge. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species – in which the molecular biologist Sabina Radeva bottles Darwin’s theory of evolution down to 48 prettily illustrated pages – is just such a title. Aimed at readers as young as six, the tone, for the most part, is correspondingly simple. Darwin “travelled the globe on board the HMS Beagle, visiting wondrous lands, studying animals and collecting fossils”. When he came home, he “worked from his English country house, where he lived with his wife, eight children, and his dog Polly!” We see him visiting an orang-utan at London Zoo.

But when it comes to Darwin’s revolutionary theories, the book gets deceptively informative. After tackling the basics (species: “groups of living things that look alike and can have babies together”), we gallop straight to beefy ideas such as “Variation under Nature” and “Variation under Domestication”: “We now have over 340 breeds of dog! People have raised them for their different sizes, shapes, colours and even talents. Yet all of these breeds came from one kind of wild wolf, many howling moons ago!”

Some six-year-olds may be daunted by chapter titles such as “Imperfections of the Geological Record”, and “Mutual Affinities of Organic Beings”, not to mention an appendix that covers “Epigenetics” and “Comparative Embryology”. But Radeva wears her erudition lightly, and her breezy style will sweep even the less confident readers along (“we’ll never know just how weird and wonderful many extinct species might have been!”). The result is a triumph of concision that appeals both to the budding young scientist and to the adult who has given up hope of ever reading Darwin in the original.

Order Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species from the Telegraph Bookshop

Charlie Changes Into a Chicken by Sam Copeland (Puffin) ★★★★☆

Sam Copeland has been a literary agent for umpteen years, and has launched many an unknown author on the road to success. Now the roles have been reversed. He has written one of most hyped children’s book debuts of the decade, complete with film rights and 20 foreign translations. “This is Charles McGuffin,” the novel begins, beside an illustration of a boy holding a toy plane. “It isn’t actually him. It's just a picture of him. OF COURSE. If you hadn’t figured that out, this book will be way too difficult for you.”

Copeland, on the other hand, makes it all look way too easy. His book is a masterclass in publishing savvy. It is aimed at readers of eight who, as any agent will tell you, are not interested in lyrical prose. Jokes are what sell, and from the opening paragraph Copeland strikes just the right larky tone. The hero is “like you and me” (commercial tick) except for “one MAJORLY HUGE, MASSIVE difference”, which is that he can change into animals. (“One minute he’s a normal boy, the next minute he’s a wolf. Or an armadillo.”) In chapter four he becomes a pigeon, narrowly avoiding the clutches of his child-hating head teacher (tick) Ms Fyre, who lurks in a sweltering office full of orchids.

But it is more than a comic caper. Charlie is a thoughtful child, and his transformations are brought about by anxiety. He is worried about his brother, who is in hospital, and about Dylan, the bully at school: “We are enemies, Charlie, and we can never forget that. We are destined to fight.”

So here is the modern masterpiece: a book that is full of laughs, while also exploring childhood anxiety – currently one of publishing’s favourite themes. Hats off to Copeland for this is a touching and engaging story, even if it’s so slick you can almost hear the cash tills ringing. Order Charlie Changes Into a Chicken from the Telegraph Bookshop

The Truth about Old People by Elina Ellis(Macmillan) ★★★★★

If we are to believe a recent survey, more than five million British grandparents are now regularly relied upon as babysitters – which may explain why they have become ever more popular material for children’s books. Grandpa Christmas by Michael Morpurgo and Great-Grandma and the Camper Van by Lois Davis are among a flood of recent examples. There are five different books on sale called I Love You, Grandma, not to be confused with Grandma Loves You, of which there are four. Now for the budding anthropologist comes a book that boldly sets out to reveal The Truth About Old People.

The story is told in the words of a little boy, whose findings are based on his own grandparents – both “really old” with “wrinkly faces” and “a little bit of hair”. The boy has been hearing “lots of strange things about old people”, most of them negative. Some people have told him that old people are “not much fun”; others that they are “slow” and “clumsy” and “scared of new things”. But, as Ellis’s drawings charmingly reveal, the truth is very different. In one picture, the grandparents cavort with their grandson on roller skates; in another, they dance a jig in their drawing room. In one illustration – contrary to reports that “old people definitely don’t care for ROMANCE” – they are (eek!) shown kissing. “Old people are… AMAZING!” the boy concludes, as his grandparents race into the sunset on a tandem.

The publisher’s claim that the book “tackles ageism” is perhaps overstated – this is a defiantly upbeat book, which does not concern itself with any geriatric nitty-gritties. (Most grannies would not risk the consequences of bouncing bare-legged on a trampoline.) But grandparents are the rising stars of children’s fiction – and this simple, touching story shows why.

Order The Truth about Old People from the Telegraph Bookshop

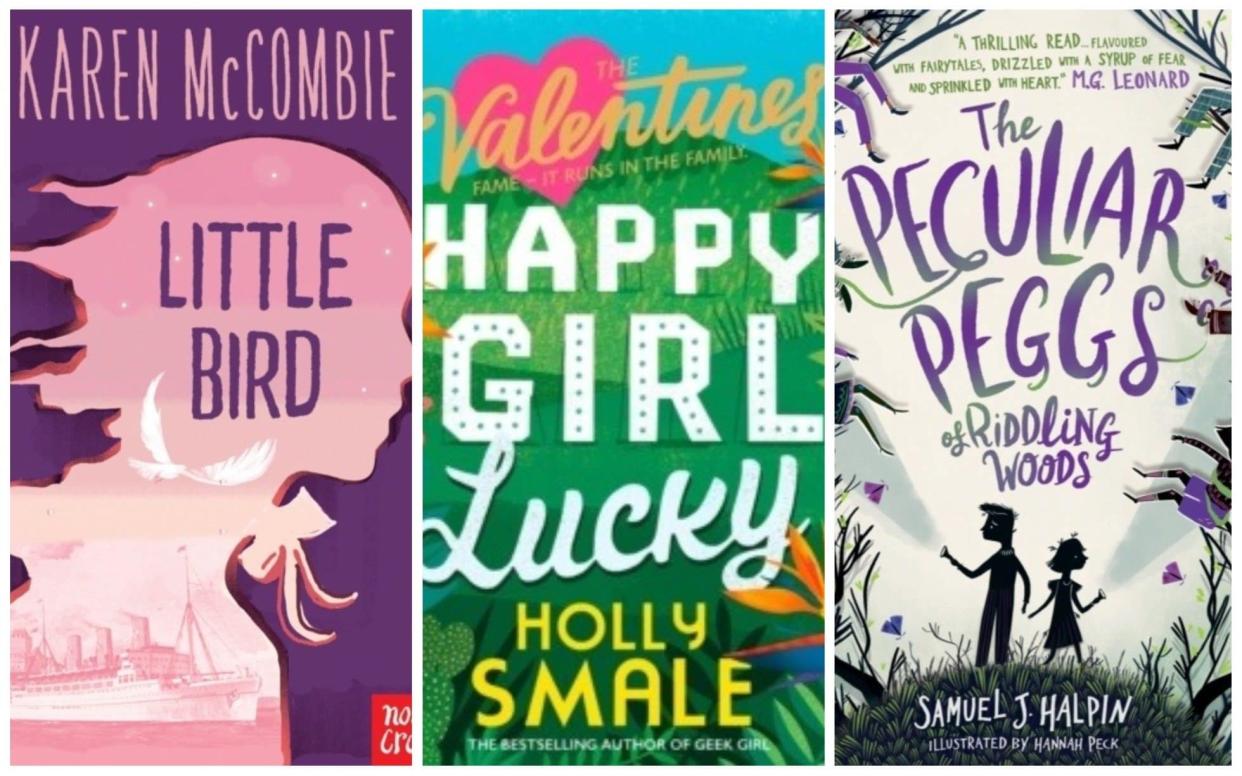

Happy Girl Lucky by Holly Smale (Harper Collins) ★★★★★

OMG!!! Here it is! The long-awaited new series by the high priestess of teenage fiction, Holly Smale. Geek Girl, her phenomenally successful debut novel, told the story of Harriet Manners, an unfashionable 15-year-old who is spotted by a modelling agency. This time, the heroine is Hope, who lives in London with her brother and two sisters, and is feted wherever she goes: “We’re one of the most famous families on the planet. A dynasty of movie stars stretching back four generations… We are the Valentines.”

Hope is destined for stardom (“My parents took one look at my beaming, newborn face and thought: There’s a girl who’ll embody rainbows, sunrises and the kiss at the end of a film”). But her gilded life is mired by family dysfunction – which has culminated in her mother being admitted to a rehabilitation home, following an apparent breakdown: “Her platinum-blonde hair is perfectly smooth, her eyes are closed and one hand is held delicately against her forehead… My mother really knows how to command a scene.”

As does Hope, who spends much of the story squabbling with her sisters, and getting in high dudgeon that she is not allowed her full share of the limelight until she is 16: “When I’m finally unleashed on my adoring, impatient public, I’ll be so talented and glamorous that my world-renowned siblings will collapse with jealousy” and “beg me to explain my wondrous movie star ways”. This is a far cry from Noel Streatfeild. Yet Hope is also is an eagle-eyed narrator who captures her family’s eccentricities brilliantly. “My eyelashes must have been fluttering too fast to see properly,” she says near the start. But the triumph of this book is that she never misses a thing.

Little Bird Flies by Karen McCombie (Nosy Crow) ★★★★★

Karen McCombie is best known for her long-running Ally’s World series, the adventures of a 13-year-old girl under titles such as Sisters, Super-Creeps and Slushy, Gushy Love Songs. But in the course of 80-odd books, McCombie has shown she has many strings to her bow. Her latest novel makes a seamless leap to the Victorian Highlands, and the fictional, storm-battered island of Tornish.