Believing painters describe sacred art as a stillness practice

For nearly 2,000 years, art has been a way for Christian believers to remind themselves about the reality of “things that are not seen, which are true.”

The earliest Christian art dates back to second-century wall and ceiling paintings in the Roman catacombs, with the first illustrations of Jesus found in Syria during that same era showing a beardless man with close-cropped hair.

For some early Judeo-Christian believers, creating or featuring art was seen as a violation of the Biblical command to “not make unto thee any graven image.” Yet many other people of faith over the ages have seen art as a way to glorify God.

From Leonardo’s da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” (1498) — the most reproduced religious art in the world — to Frans Schwartz’s stunning “Agony in the Garden” (1898), thousands of paintings were created by believing artists over the years, bearing witness that a Savior had, indeed, come.

Art today is a crucial part of Latter-day Saint life — adorning temples, chapels and homes, as well as the many magazines and manuals that members turn to for assistance in understanding and living God’s word. An international art contest among members — now in its 13th year — features online galleries of diverse art from as many as 148 artists worldwide at a time. In recent years, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has taken steps to encourage even more Christ-centered art in chapels to convey a “deeper reverence” for the Savior.

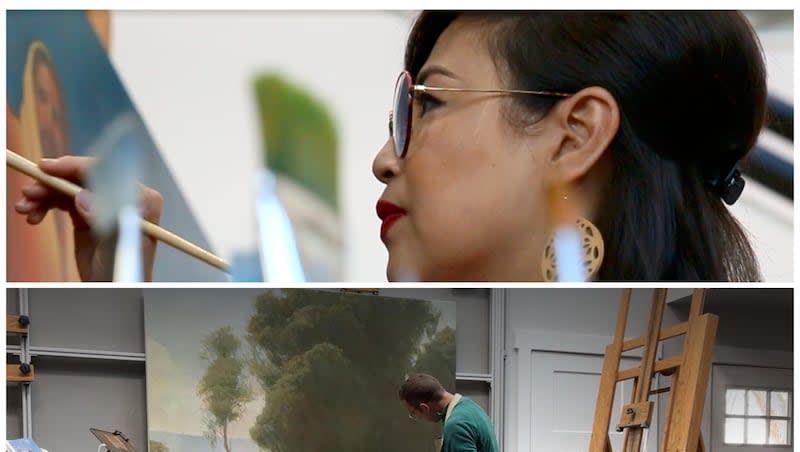

The Deseret News spoke with 15 Latter-day Saint artists to go deeper in appreciating the experience and personal impact of creating high-quality, visual portrayals of Jesus Christ.

Communicating without words

“We don’t worship the art, but it sure helps to have somebody to look to,” says painter Annie Henrie Nader. This is perhaps especially true when words alone don’t seem adequate to capture a profound emotion or a sacred reality.

“Speaking and words aren’t my thing,” says Kate Lee with a smile — happy that art offers her another way to get “emotions on paper.” As Leonardo da Vinci once said, “Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt.”

After her own experiences feeling consoled by the Savior, Annie Cole says, “He understands more than I am able to say.” Feeling hesitant at her ability to capture that through words alone, the charcoal artist seeks to express her “feelings through drawing.”

“You really feel like you’re giving something to the world,” Karen Foster told me about her own painting — even though she sometimes wonders whether we’ve become overly “saturated” with this kind of art.

While it’s true there has never been more high-quality images of the Savior created around the world, it’s also true that these sacred images are a small subset of a visual landscape dominated by an onslaught of profane and unsettling images confronting people every day.

Bringing sacred words to life

“I typically will start a painting based off of a few verses of scripture, or a list of attributes of the Savior,” says Esther Hi’ilani Candari — describing a pattern of preparatory reading and rereading, including consulting different translations and the etymology of key words.

Rod Peterson describes thousands of doodles in his scriptures, recording thoughts and impressions — some of which he eventually turns into a larger painting.

Even though she has read scriptures many times, Eva Koleva Timothy says that when she’s preparing to create another piece of art, sacred texts “come alive in a new way that I’ve never felt or noticed personally.”

“I want to be an observer — personal, close to him, observing what he was going through,” Nader says, describing her portrayal of the “Garden Meditation,” where she tried to portray a “depth of calmness” she believes the Savior must have had, even while the disciples were panicking.

A patient unfolding

Nader describes how a visual sometimes comes to mind right before falling asleep, or while she’s spending time in the temple or scriptures. “Hey, that’s a way you could portray mercy or hope.”

“I rarely, if ever, see the finished painting in my mind before I begin,” Michael Malm writes — rather, an “overall impression” changes as he works with the details of paint as “the painting reveals itself to me slowly one piece at a time.”

He describes being led by small impressions, including a “feeling that something isn’t quite right yet.” Malm adds that “quiet time with the painting helps me to discern what the painting needs.”

“I’ve never been inspired to paint a picture in a frenzied moment,” says Justine Peterson. Greg Olsen highlights the stillness involved in creating a painting “alone in my studio, where I meditate or listen to music.”

When asked why his paintings so regularly portray the Savior in a moment of stillness, Olsen says, “So often the Lord found guidance and relief in stillness. Since He’s the way, the truth, his life also provides a template for us in how to do our mortal life.”

“We also need to learn how to be and be still and remember,” Olsen reiterates, rather than only asking, “What more should I do?”

An invitation to slow down and go deeper

“Art itself kind of requires stillness to enjoy it,” adds Olsen. Compared with music that can so quickly “sweep you off your feet” and “take you wherever,” the visual arts invite people to “slow down, be still and create a conversation with the art.”

“If you do that, and pay a little bit of a price,” he says, “asking some questions and imagining some answers,” this deeper engagement “can give back to you a great deal.”

Yet “a lot of people don’t slow down to think of the impact of religious art,” says Candari. That leads people to “miss out on the actual “feast of what actually can be offered.”

Within a “TikTok economy” that pumps out “fast food for the mind,” Candari observes that it’s now common for people to struggle deeply engaging anything at all — reflecting a collective need to “fight against the downhill slide” culturally that pulls so many of us away from genuinely immersing in any content (written, visual or audio) at what she calls a “feast level.”

Justine Peterson compares artwork to prayer and gospel study in the inner patience required. In a world full of so many deceptively quick answers, however, she admits, it’s “sometimes harder to look at things that are slow and quiet” — “hard to accept that it works.”

Peterson argues as well that the “quick generation of (AI) art is not the same” as what personal art can provide.

Needing ‘something deeper’

Nader didn’t do much religious art previously — instead focusing more on getting into galleries, which tend to be secular. After going on a mission to England, however, she came back newly curious: “How does art actually help people?”

During her time sharing the gospel full time, Nader had met so many people needing “big help” — reflecting, “they didn’t just need a pretty picture on the wall. They needed something deeper.”

It was still a leap of faith for this woman to create sacred art — recalling her worry, “I don’t know if anyone will buy a single painting.”

Nader now appreciates how art can provide a “unique way to share the gospel.”

“I want my pictures to help people feel and understand that he was a real person,” Brent Borup says, “born in real life and not just however you want him to be. He is a real person, with a body.”

“Really this is my testimony,” Rose Datoc Dall also says. “I’m painting my testimony,” Chad Winks agrees, “my visual testimony … I just really want people to see how Christ has impacted my life.”

“This really happened,” Del Parson says about his depiction of the First Vision of the Savior in New York. “How can I depict this? It really happened.”

Rod Peterson describes drawing paintings of Christ since he was 9 years old. Over the years, painting has been a “way for me to build my testimony and share it,” he says, adding, “My greatest desire is to share my testimony of Christ with others.”

Painting together as a family

Three different painters interviewed spoke of painting as a family affair — with husband-wife teams working together, sometimes even with their children. Brent and Jeanette Borup both create art of the Savior.

Rod and Justine Peterson met after studying art together in college in 2010, continuing to create art today, with Rod painting in oils and Justine drawing in pastel and painting in watercolor. If there was any doubt about a familial passion for art, they also have three sons, Van Gogh, Rembrandt and Raphael.

They describe painting as helping “shape our family’s foundation on Christ” — with Justine saying, “The whole purpose of why we paint is to share our testimony.” The Peterson family art often, unsurprisingly, features family and relationship themes from the Savior’s life, such as Rod Peterson’s “Suffer the Children,” where a child puts a crown of flowers on the Savior’s head — or Justine’s “Waiting on the Carpenter,” depicting Mary holding Jesus in her arms watching as Joseph arrives home.

This was “not just a boy who would learn his father’s worldly trade,” Justine writes, “but the boy who would learn a Heavenly trade and grow to carve and shape all of mankind’s souls as the Savior and Carpenter of the World.”

Kelsy and Jesse Lightweave also combine photography and illustration in a family hobby that’s changed the way they spend time together.

One composite image they worked on together, “Descension,” depicts a moment angelic light provides a small amount of comfort to the Savior in Gethsemane — a moment, they say, when “Heaven and Hell collided.”

Humbled by the creation process

Over and over, these artists speak of how “humbling” it is to create art of the Savior. Nader speaks of deepening realization that “we have a master artist who created everything” and who “gave us abilities.”

“I feel like glorifying God, and so humbled every time,” says Eva Koleva Timothy. “I’m just a little pencil in God’s hands,” she says, citing Mother Teresa. “He does the writing.”

“As we open our hearts to God to be our guide as we create,” Timothy says, “he creates with us.”

“He would need to be a part of the creation,” writes Kristin Yee, second counselor in the Relief Society General Presidency for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, reflecting on her own art of the Savior. She describes choosing to trust her “white canvas to Him.”

Yongsung Kim, who is not Latter-day Saint, expresses his gratitude that he can “work miracles for God” as he witnesses the impact of his art on people.

“I don’t feel like I’m anything wonderful or special,” Dall says. “If people are touched that must be the Spirit — it has less to do with me.”

“The Lord may use it in unexpected ways,” she says of her paintings. “I’m humbled if someone is touched by it.”

There is precedent for these kinds of sentiments in earlier Latter-day Saint art, with Minerva Teichert (1888-1976) journaling about feeling she had been “commissioned” to help tell the “great” Latter-day Saint story.

“What I do I am driven to do,” Arnold Friberg (1913-2010) also said. “I follow the dictates of a looming and unseen force.”

“I try to become like a musical instrument, intruding no sound of its own but bringing forth such tones as are played upon it by a master’s hand.”

Help to pierce the veil

Artist Eva Koleva Timothy joined the Church of Jesus Christ at age 15 in Bulgaria — feeling still today “so grateful for the gospel and the missionaries who found me.” While she’s always loved Jesus, the part that feels “incredible” is that her passion is “going to go even deeper.”

”It’s amazing that you can have the gospel and your relationship with the Lord keeps getting better if you want it.”

Years ago, Timothy began feeling that she needed to “create art work for God.” She responded with some confusion, “What? I don’t even know how to do that.”

“This needed to be a matter of consecration,” Rose Datoc Dall remembers feeling in her own life, so that “I would have the Lord’s help.”

“Painting religious subject matters does take faith,” Dall says. “And if I forget to really seek guidance, I get stuck. I can’t paint the life of the Savior and not seek guidance — it just doesn’t work.”

It’s striking how often Latter-day Saint artists seek ways to help their viewing audience pierce the veil, as it were, such as this portrayal of “Silent Angels” from Annie Cole, “Angels Among Us” by Annie Henrie Nader or “She Will Find What is Lost,” by Brian Kershisnik.

“Eternity seems very real to me,” Teichert wrote in her 1937 autobiography — a contrast to how distant and far away sacred matters feel to so many today.

Even after creating a thousand pieces of art, Teichert expressed a desire to “be able to paint after I leave here. … One lifetime is far too short but may be a schooling for the next.”

Based on these conversations with Latter-day Saint artists, Teichert is hardly alone in anticipating a heavenly future full of rich art to come.

For an earlier segment of this investigation, see “Painting Jesus — Believing artists talk about the personal impact.”