Baseball's Black Sox scandal drew to a close 100 years ago — in a Milwaukee courtroom

The final chapter of baseball's biggest scandal closed in a Milwaukee courtroom 100 years ago this month.

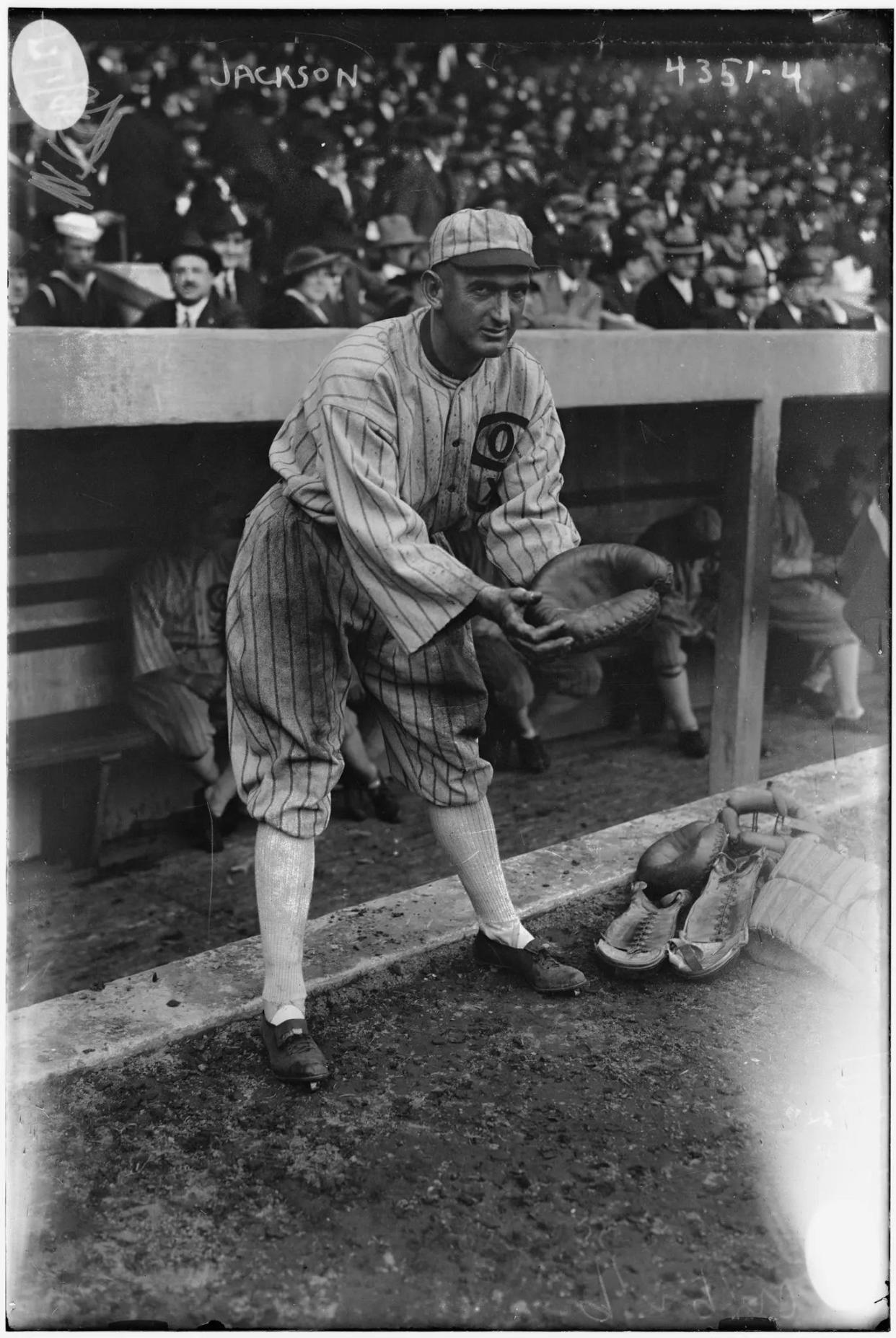

One of the game's biggest stars, "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, sued the Chicago White Sox, saying the team owed him $16,000 in back pay. Jackson had signed a three-year contract after the 1919 World Series — the same World Series in which Jackson and seven of his teammates were accused of throwing games in exchange for money from gamblers.

When what became known as the Black Sox scandal surfaced, the team refused to pay him.

The Milwaukee trial, which began Jan. 29, 1924, was a front-page story, took some unexpected turns and had a surprise ending.

And then the record of the two-week trial was nearly lost to history.

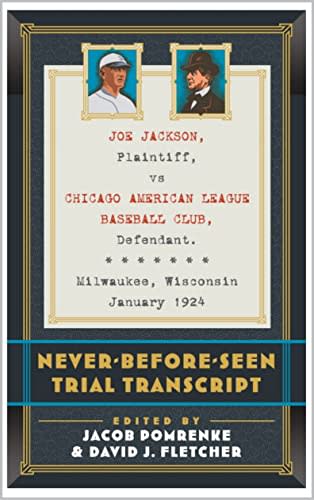

But thanks to the efforts of Chicago baseball historians David J. Fletcher and Jacob Pomrenke, the details of the trial have been brought back into the light, in a mammoth book with a mammoth title.

"Joe Jackson, Plaintiff, vs. Chicago American League Baseball Club, Defendant. Milwaukee, Wisconsin January 1924: Never-Before-Seen Transcript," a 658-page reproduction of the 1924 trial's transcript, was published last fall by Chicago-based Eckhartz Press.

“To me, it reads so well, it’s almost like a screenplay with a dramatic ending," Fletcher said.

Before the book came out, the transcript had been seen by fewer than a dozen people. But it includes rare testimony of the scandal's key participants, including Jackson, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey and even some of the gamblers.

And their words do a lot to correct the popular version of the Black Sox story depicted in "Eight Men Out," the Eliot Asinof book and the John Sayles movie it inspired.

“It’s a very dramatic story, the one that most of us grew up learning, the ‘Eight Men Out’ story, and the film only solidified that and also added some errors as well," Pomrenke said. "It’s a very compelling narrative. The problem is that it’s not very true.”

How did a Black Sox trial end up in Milwaukee?

So why did a trial involving a Chicago ballplayer and his Chicago team happen in a Milwaukee courtroom?

As with many parts of the Black Sox story, it started as subterfuge.

When the American League was formed in 1901, it happened under the shadow of baseball's other major league, the National League. To secure a franchise in the Chicago Cubs' home market, the White Sox and the American League were both incorporated beyond their reach — in Milwaukee.

So when Jackson's attorney, Ray Cannon, filed suit against the White Sox, he did it in the old Milwaukee County Courthouse, in what is now Cathedral Square Park.

"Imagine that happening today — a star baseball player suing his team, and it actually going to trial," Pomrenke said. "It would never happen. They would find a way to settle that case. … They would never allow these questions in open court."

Shoeless Joe swings and misses

Through the transcript, you get how the scandal played out in the participants' own words. Jackson, for example, explains what he did with the $5,000 he received from the gamblers: He paid his sister's hospital bills.

"You still have a lot of people who feel that Joe’s completely innocent, but there’s no disputing he took the money," Fletcher said. "And this is the best document (that) explains exactly what he did, and the evidence is there.”

The gamblers' testimony underscores another rejection of the "Eight Men Out" narrative: that the Black Sox players were innocents, taken advantage of by greedy baseball management and corrupted by the gamblers.

“Despite all the myths, this was not something the gamblers initiated," Fletcher said. "This was something the players did.”

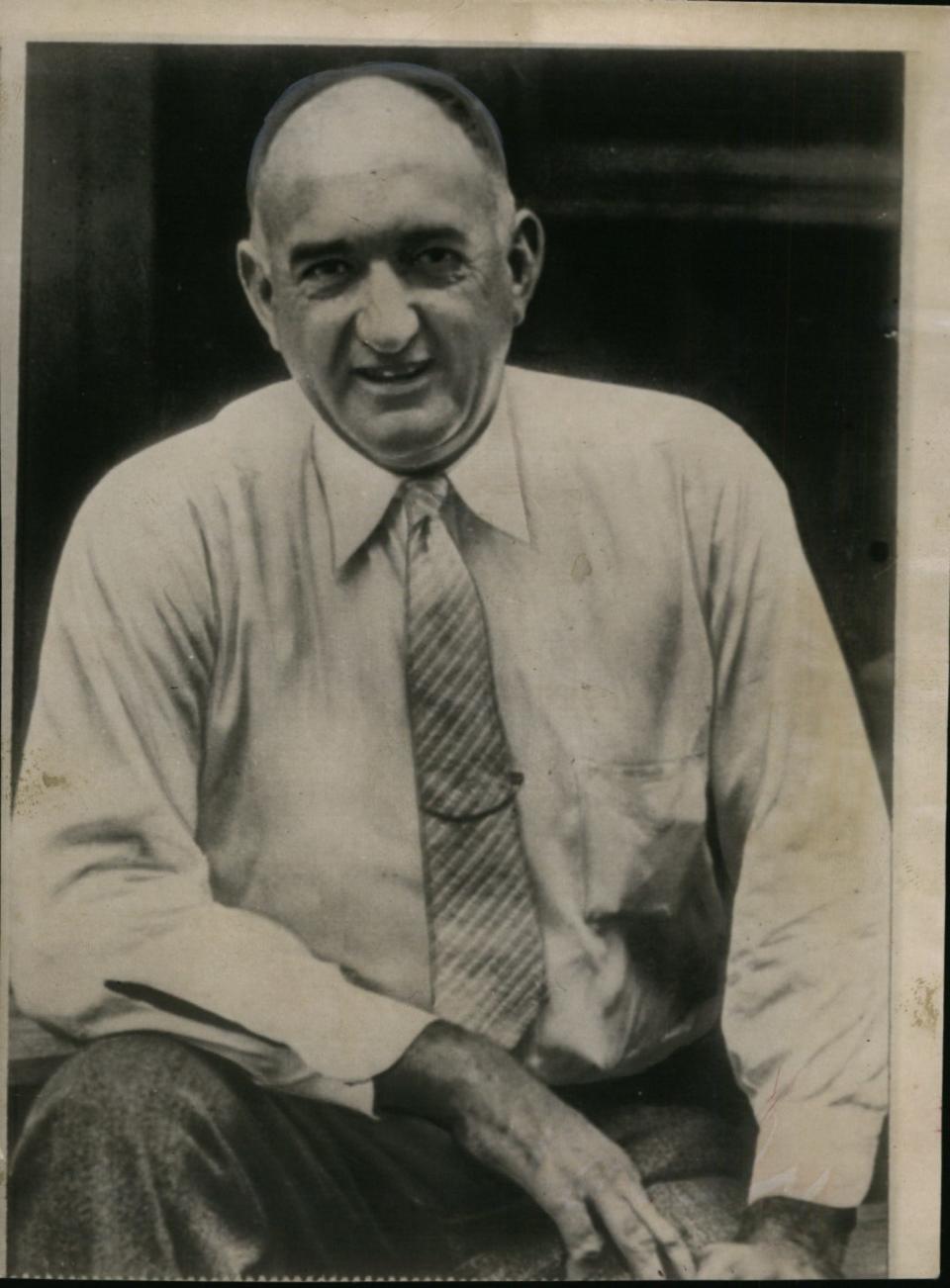

In court, Cannon relied on expert witnesses saying they thought Jackson had played to win. Among his best witnesses was Comiskey himself, who like Jackson spent about four days on the stand.

“He basically gives them their case, says Jackson didn’t cheat, he played to win, and (he) didn’t see anything” compromising in his play, Fletcher said of Comiskey.

But Cannon stumbled in court, too.

Jackson's testimony contradicted what he told a grand jury in 1920, a fact drummed into the proceedings by Comiskey's lawyer but something Cannon did little to mitigate.

When the jury ruled in Jackson's favor, Judge John G. Gregory surprised everyone by throwing out their verdict, saying Jackson had perjured himself in the Milwaukee trial. The baseball star wound up with nothing.

Printing the legend for 100 years

One thing that comes through in the transcript is the extent to which gamblers were mixed up in baseball — and that everyone knew about it. A number of high-profile players had fixed games in the past and received no more than a slap on the wrist.

“Ultimately, what the Black Sox scandal is all about is, the players saw an easy opportunity to make some money. There was a high-reward, low-risk proposition," Pomrenke said. "Even if they did get caught, they knew they weren’t going to get punished because nobody else who had been caught fixing games had really been punished before.”

But after baseball's first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, surprised the players by banning them from the game for life, the narrative changed. The eight Black Sox players were rebranded as an exception, not the rule.

“They play out this innocence card, and the eight Black Sox — that was it," Pomrenke said. "They were the crooks, they were the only crooks, and nobody could have known, and nobody could have done anything about it. And it’s not true at all.”

The rapid rise in legalized sports betting today makes getting out the accurate story of the Black Sox scandal more timely than ever, Fletcher said.

“It’s ironic how full-circle things have become,” he said.

Getting the transcript into circulation is just the latest corrective presented by researchers into the Black Sox story.

“We’ve spent a lot of time, especially the last 20 years, finding evidence, finding documentation,” Pomrenke said.

Fletcher added that they are working on a legal analysis of the Milwaukee trial for a book due out later this year. The 1924 transcript should continue to yield dividends for researchers trying to set the story straight on the Black Sox.

“The phrase that we like to use is that the Black Sox scandal is a cold case, not a closed case,” Pomrenke said.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Records of 1924 Milwaukee trial shed new light on Black Sox scandal