Art Spiegelman interview: ‘My compatriots on the Left are so f-----g humourless’

When Art Spiegelman was offered the commission for his latest project – to illustrate a “novelette” by the veteran author Robert Coover – he accepted with his standard disclaimer. “I wrote back to say, ‘As long as it has no mice or Jews, I’d like to see if I can do this.’”

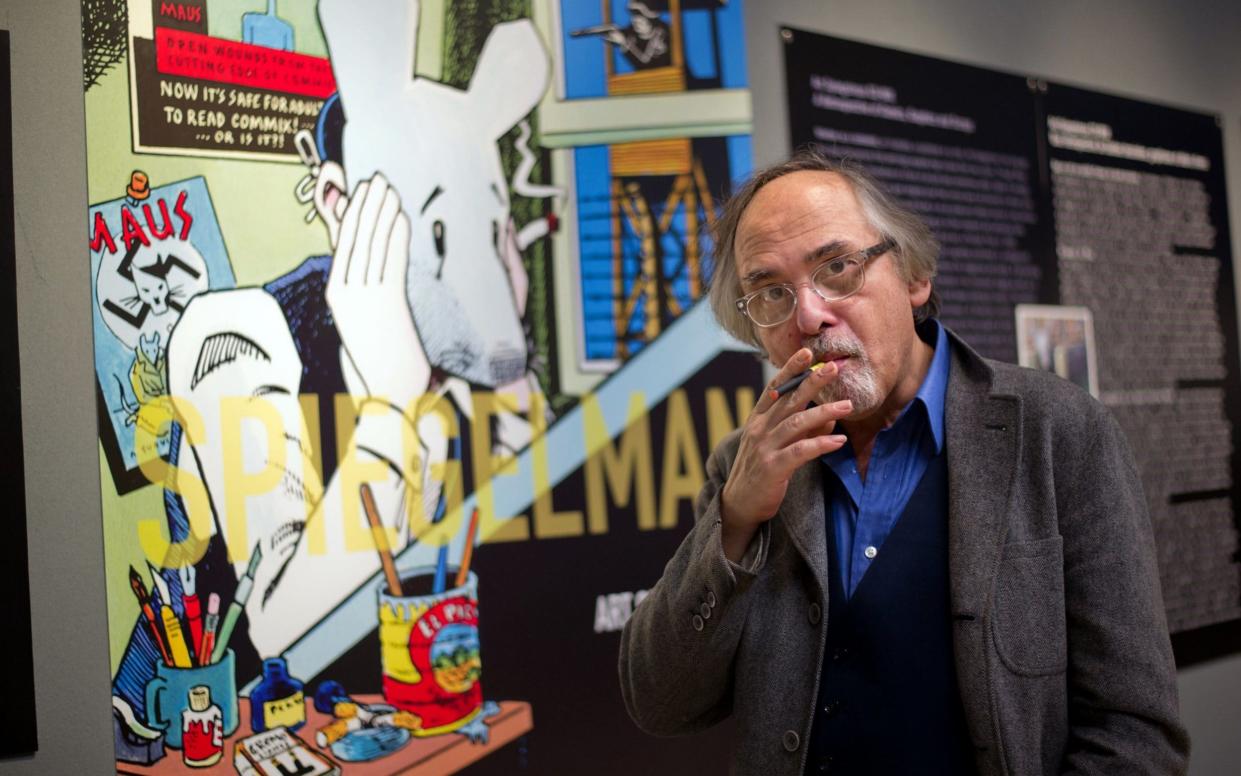

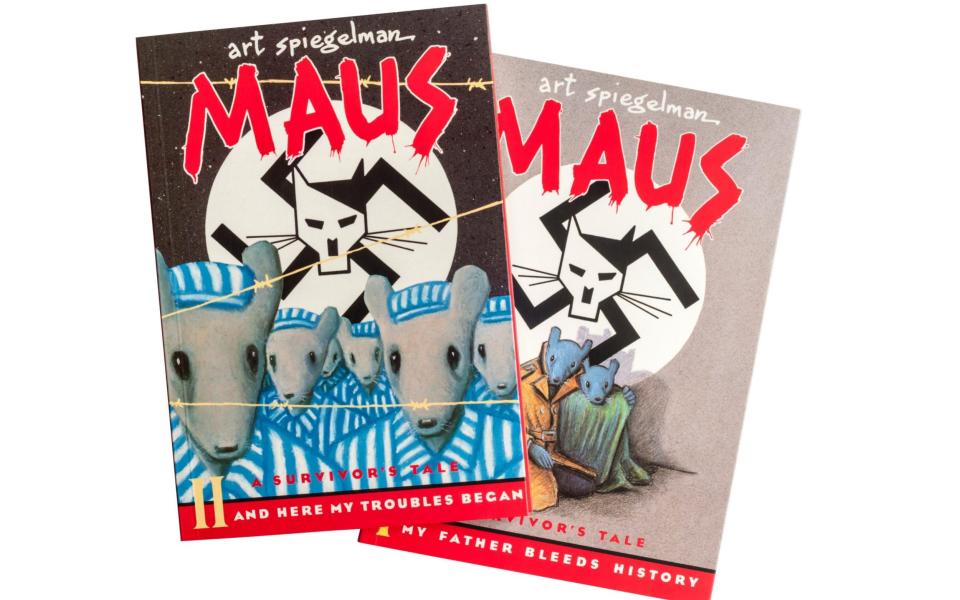

Where some artists get pigeon-holed, Spiegelman has become mouse-holed. His most famous work is Maus, the 1980s comic book based on his parents’ tribulations in Auschwitz, which defamiliarised and recaptured afresh the obscenity of the Holocaust by depicting Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. But its brilliance has overshadowed a huge body of work that has tackled many themes in many different styles.

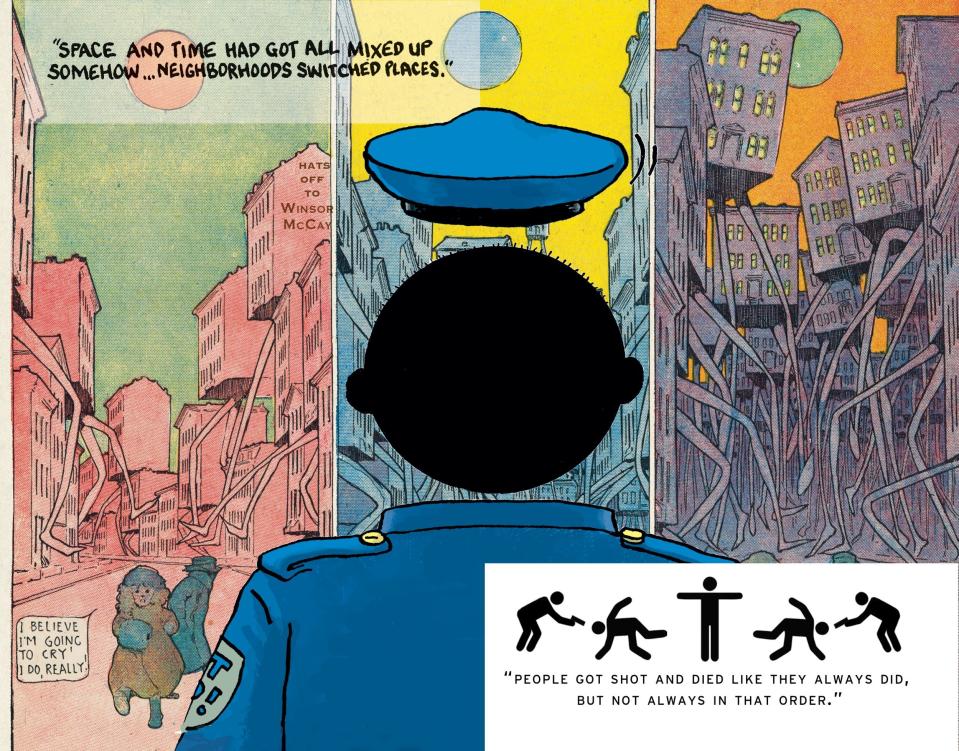

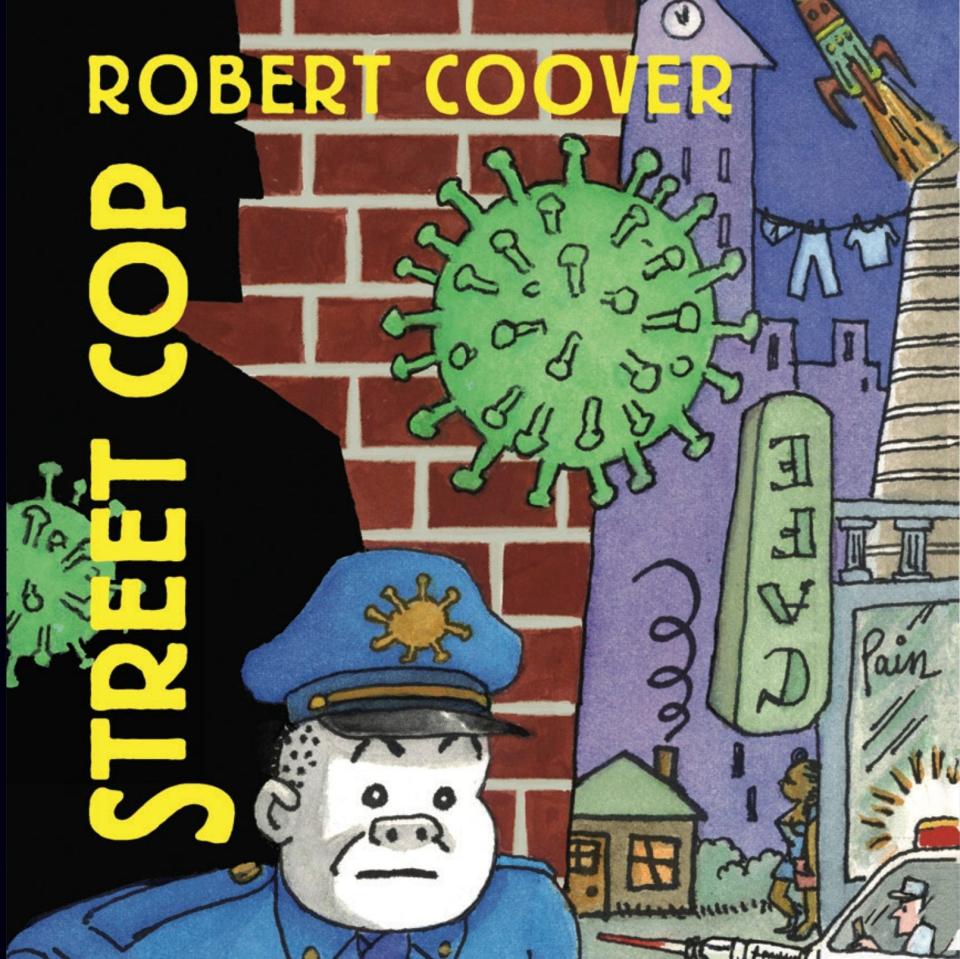

His illustrations for Coover’s Street Cop – Spiegelman’s first major artistic project in a decade – recall some of the work of his surreal, scatalogical underground heyday in the 1960s and 1970s.

They prove to be a perfect fit for Coover’s nightmarish text, set in a dystopian US city in which robot police-officers tackle crime, and the narrator – an unnamed human cop – is given the donkey-work of clearing up the havoc they leave in their wake.

Spiegelman, 73, has never met the 89-year-old Coover in person, but the pair collaborated on the project over Zoom. He was seduced by the small scale of the enterprise: Street Cop, measuring 4 x 3 inches, is published by isolarii, a new house specialising in beautifully produced mini-books by avant-garde authors.

“There’s a writing project I’ve been immersed in, and I wanted to learn to move my hand again. With this, the stakes seemed low. It thrust me way back into my underground comic roots, when almost no-one would see or read what I did. Back when I wasn’t geared toward finding an audience, I was geared toward finding out what’s going on inside my head and taking an inventory.”

The inventory here reveals a mind that draws on the comics of the past. There are subversive cameos for Tintin and other classic characters, while Street Cop is a grown-up version of Sluggo Smith from the long-running US newspaper strip-cartoon Nancy. News of the present also looms large: Covid molecules drift menacingly through Spiegelman’s mean streets.

Spiegelman’s Covid year has mostly been spent with his wife Fran?oise Mouly, the art editor of The New Yorker, at their log cabin in north-west Connecticut. He is talking to me today from outside the cabin, looking dapper in pink shirt and fedora and vaping away as he talks 19 to the dozen against a soundtrack of twittering birds, veering between comic patter when talking about himself and heartfelt diatribes when discussing politics.

The chaos of the would-be insurrection at the fag-end of the Trump presidency dismayed Spiegelman, but also “re-opened the book” for him after a period of struggle, inspiring his illustrations for the apocalyptic final scenes. The events around the death of George Floyd inevitably seeped into his portrayal of the cops, too.

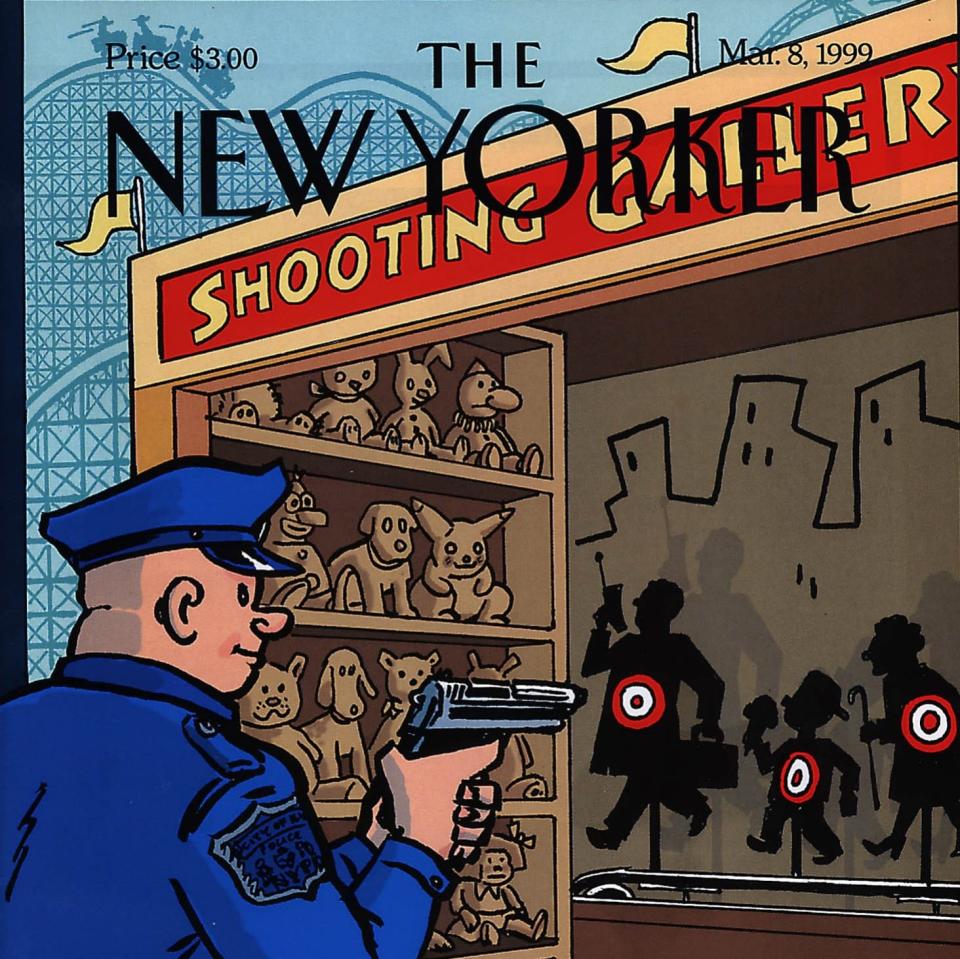

Police brutality has always preoccupied him; one cover he drew for The New Yorker in 1999 – of a policeman targeting civilians at a fairground shooting gallery – led 250 officers to picket the magazine’s offices. “This police state brutality is nothing new. It was around when I was a kid during the Vietnam War protest era. It’s hardly news, but now it’s at the front of the news where it belongs, and it’s good to see it there.”

Some people have already complained, however, that one joke in Street Cop does not befit an ally of the BLM movement: a drawing in which the owner of a zombie pet shop wears an apron bearing the words: “Dead Lives Matter Too!”

“That wasn’t aimed at Black Lives Matter at all. This is the reductio ad absurdum of stretching that phrase to Blue Lives Matter, All Lives Matter, trivialising BLM. Probably there are other things that somebody could take umbrage to, one place or other in the story. Umbrage is really easy to take.

“One of the saddest things to me about my compatriots on the Left right now – it’s so f-----g humourless. Humour’s strongest quality is to make you think, and usually that involves saying something true that somebody won’t hear at that moment. The only humour that’s ok is sanctioned methods for sanctioned targets, like Donald Trump, even though the consequence is making him feel even more powerful than he had any right to feel – if you feed a narcissist he gets bigger, it doesn’t matter if you spit at him or lick him.”

I wonder if he thinks that comic books lack fire in their bellies these days – and whether that can be attributed in part to him, with Maus making the genre critically respectable and giving rise to the genteel euphemism “graphic novel”.

“You’re right that my goal as a kid was to be able to find a readership that wasn’t just interested in reading about the Hulk or the Thing, and that audience really flourishes now. Comics tend towards a sameness for me now, but there’s room for people to be as ornery as they used to be if they want to stay small-press, which is what we were. There’s one man named Eli Valley who does anti-Zionist cartoons that seem to be able to raise as much ire as any drawings ever made – hats off to him.”

There’s a telling scene in Maus in which journalists bombard Spiegelman’s character with questions about difficult topics such as Israel, until he shrinks down to the size of a baby and starts wailing. It’s with some trepidation, therefore, that I ask him what he thinks about the current situation in Gaza.

“This is so painful, y’know? I just feel so lucky that my parents went right instead of left [as Polish Jews who emigrated to America after the Second World War]. It seems to me there’s a different focus on this than on the zillion bad actors on the rest of the planet – and that often, at least in America, drifts into a kind of anti-Semitism that I tend to take personally.

“But my feeling is that America shouldn’t be subsidising this terrible thing. My sympathy, and my charitable giving, often goes to Palestinian causes, not because I think the Palestinians are pure but because somehow the text of Maus leads me into having to support them.”

For many years Spiegelman has refused to talk about Maus, insisting he had said everything he had to say. “But in the last year or two I started accepting lecture gigs to talk about that book. Because I can smell trouble, this romance developing [in America] with fascism and autocracy, certainly a brand of pre-fascism.”

Recently he spoke over Zoom to a group of doctoral students in genocide studies. “One person wrote in the chat room: ‘Aw, politics! I thought we were here to talk about the Holocaust!’ I interrupted what I was saying and said, ‘The only reason I’m here is because of idiots like you.’ If I was quick-witted enough I would have said: ‘I’m sure you consider yourself to be a good Jew but I can only see you as a good German.’ The reason I was there was to make those parallels with what’s going on now.”

For now, it’s back to writing rather than drawing: he’s working on a television pilot for Amazon Prime with Neil Gaiman and director Azazel Jacobs. He won’t tell me any details, but Jacobs, an old family-friend of Spiegelman’s, has a connection with Maus going back decades: his father, film-maker Ken Jacobs, once remarked to Spiegelman that in early cartoons mice and African-Americans were often portrayed similarly, sowing the seed for the idea of Maus. Gaiman, meanwhile, has an exclusive deal with the streaming giant.

“The people I’m working with know a lot more about how television works than I do,” Spiegelman says. “It’s one of my many forays into areas I have no business in. I’ve done musical theatre, something I have no interest in at all. But I always take up these invitations. Is it because I’m an idiot savant, or just an idiot? Of course, half the time I come out an idiot.”

Street Cop is available now to isolarii subscribers and to non-subscribers on June 10

Solve the daily Crossword