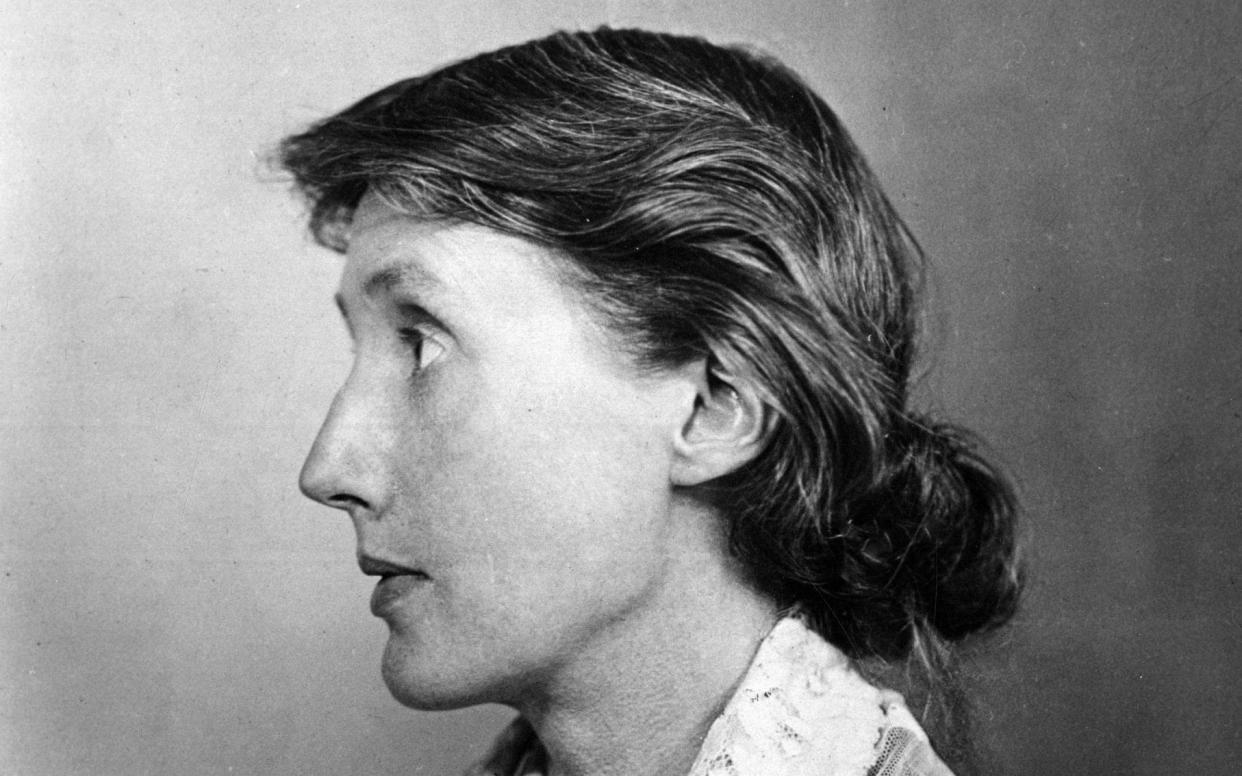

'A loss which can never diminish': Why Virginia Woolf remains one of literature's most alluring writers

Virginia Woolf, so today’s Google Doogle tells us, would have turned 136 today. It’s somewhat of an arbitrary celebration – not least because Woolf famously took her own life at 59 – but the point remains that she is one of British literature’s most indelible figures.

Woolf, for the uninitiated, helped to define the modernist movement that shook up the arts in the wake of the First World War. Along with James Joyce and poet TS Eliot, she pioneered the stream of consciousness mode of writing that bled into narratives to give readers insight into the thoughts – rather than just the mere actions – of her characters. In Mrs Dalloway, published in 1925, this meant a still-rare insight into the crises of a menopausal woman and a suicidal soldier suffering from PTSD. When, six years later, The Waves came out, Woolf defined six characters almost entirely through their inner monologues.

The provocation of her work – much picked-over by academic institutions, playwrights, filmmakers, feminists and philosophers since – would have made her name anyway. But Woolf’s biography has encouraged her readers, fans and critics to cling onto her as an object of fascination. Her publisher husband, much-romanticised social group, a subsequently glamorised suicide and a fervent lesbian affair have all made Woolf one of the more colourful literary figures – a position one feels she would be aghast at occupying.

Woolf was born Adeline (her middle name was Virginia) Stephen in 1882, into a literary household located on Hyde Park Gate, Kensington. Her childhood was filled with members of the Victorian literary set, thanks to the connections of her father, the author Leslie Stephen – whose previous wife was none other than William Thackeray’s daughter.

She and her sister Vanessa, who would become an artist, were educated at home, while her brothers went to Cambridge – something that she would later note in her memoirs and was undoubtedly a kernel of her keen feminist streak. By 22 she was orphaned – having lost her mother at 13 – and had already struggled with her mental health. Her father’s death brought on the first of a string of breakdowns that would punctuate her adult life, and she was institutionalised.

Leslie Stephen’s death led to the sale of the family home – a move that would be significant. Vanessa and their brother Adrian bought a house in Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, where the key members of what would become known as the Bloomsbury Group gathered – specifically in the imaginatively named weekly events known as “Friday Club” and “Thursday Evenings”.

Artist Duncan Grant, writer Lytton Strachey, critics Clive Bell (who later married Vanessa) and Roger Fry, economist John Maynard Keynes and political theorist and Woolf’s future husband, Leonard were among the key members. They were friends who had met at Cambridge and shared ideals of pacifism, an appreciation of the arts and a rejection of bourgeois culture. Their habits of bed-hopping and bed-swapping, certainly as the group evolved after the First World War, have made them the subject of much-romanticised fascination.

Woolf started writing in earnest in the early Twenties, aided by her husband, who published her under his company, Hogarth Press – which also put out Eliot’s The Waste Land. Her diaries – much studied for their candour, caustic asides and revolutionary insight – show the strength of her marriage, as did the much-quoted line in her suicide note: “I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.” Despite suffering from depression himself, Leonard was Woolf’s greatest champion and carer, especially during her bouts of mental illness.

He was also well aware of the swooning affair she conducted with Vita Sackville-West, a married writer and keen gardener 10 years her junior, from the mid-Twenties until 1929. They remained friends until Woolf’s death. But their relationship was more one built on intimate and intellectual infatuation, rather than physical passion – by all accounts Woolf struggled with sex after being abused in childhood, often thought the root of her misery. Sackville-West’s letter of condolence to Leonard after Woolf’s death perhaps sums up their connection: “This is not a hard letter to write as you will know something of what I feel and words are unnecessary. For you I feel a really overwhelming sorrow, and for myself a loss which can never diminish.”

For her part, Woolf expressed her fascination with Sackville-West through a novel: Orlando. Considered one of the most progressive early works on gender, the biography of a character who survives through three centuries both as a man and a woman was delivered to its inspiration bound in leather, with her initials engraved on the spine, on its 1928 publication day.

Although Woolf is primarily regarded as a novelist – To The Lighthouse, The Years, Jacob’s Room and Between The Acts fill her bibliography alongside the above – her essays and memoirs have held significance for feminists and writers, too. She is also one of those writers – like Toni Morrison, William S Burroughs, Raymond Chandler and George Eliot - who didn’t find success until middle-age: while she published her first novel, The Way Out, at 33, she was a decade older when Mrs. Dalloway made an impact.

The titular message of her 1929 essay, A Room of One’s Own, has etched itself into social theory; that a woman needs financial independence and freedom from childcare in order to achieve career success. It is this slight tome that brought us the concept of Shakespeare’s Sister – that the Bard could have had an equally talented female sibling who was shut out from artistic success – and shone a light on female authors from Aphra Benn to the Bronte sisters.

Woolf’s illness, however, pervaded. At the start of the Forties, she had completed her last manuscript – the posthumously published Between the Acts – and fell into another depression, compounded by the onset of World War II and the loss of her London nome in the Blitz. Like much of the Bloomsbury Group, she was a pacifist, and upset by Leonard’s decision to enlist in the Home Guard. She became obsessed with mortality. As Michael Cunningham would later document in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Hours, on March 28, 1941, Woolf left her Sussex home wearing an overcoat. She filled the pockets with stones, walked into the nearby river, and drowned.