Annapurna Sets a Disappointing New Normal: Helicopter Taxis

Spring 2024 was possibly the shortest ever season on Annapurna. When the first weather window opened, after ropes were set to Camp 3, everyone on the mountain had to choose: summit or go home. After that first wave of summiters descended, all the outfitters on the mountain packed and left.

But in fact, some summiters didn’t even bother to have their well-deserved post-climb cake in Base Camp. They were airlifted from Camp 3 straight back to Kathmandu.

Annapurna in two weeks

The earliest climbers reached Base Camp at the end of March and had time for one rotation to Camps 1 and 2. Then the weather turned for the worse and nearly everyone retreated to rest for a few days in Pokhara. Meanwhile, sherpas set up Camp 3 and laid the ropes to Camp 4. When a weather window opened, they all went up again, aiming for the summit.

Climbers who had arrived later in Base Camp didn’t even have a single rotation, but they were told there would be no more summit chances.

“I had to work until the end of Easter, so I didn’t have time to acclimatize,” David Nosas of Spain said. “We spent a total of nine days on the mountain!”

Still, Nosas and partner Domi Trastoy, outfitted by Satori Expeditions, tried to reach the summit on April 13. Nosas turned around at 7,400m; Trastoy went on supplementary oxygen at 7,500m and did make the top.

“My itinerary was to fly to Nepal, then to Pokhara, then to Base Camp,” said Flor Cuenca, a Peruvian who lives in Germany. “Then I went up for an acclimatization round that ended up as an unexpected summit push.”

Helicopter at Camp 3

As on all her climbs, Cuenca used no oxygen or sherpa support and carried her own tent and supplies. Once on the mountain, she hurried up to Camp 3, intending to leave her tent as high up as possible and then return for a final summit push.

“It was Mikel Sherpa (supporting Australian Allie Pepper) who suggested that we follow the rope-fixing team to the summit, but I had left my down suit in Base Camp!”

But Mikel had an idea. He asked the crew in Base Camp to put Cuenca’s down suit and warm gloves in a helicopter that was going to the higher camps. That allowed Cuenca to summit the following day.

But why was a helicopter flying to Camp 3 on Annapurna, anyway?

April 12: A long summit day

Summit day on Annapurna is usually long, but April 12 was even longer than usual. The sherpas had only fixed ropes until Camp 4. Two groups had left for the summit the night before: one from Seven Summit Treks which also included the Nepalese rope fixers, and Irina Galay of Ukraine, supported by Pioneer Adventure’s director, Mingma Dorchi Sherpa.

It is worth noting that the climbers were already tired after arriving in Camp 3. They’d just completed the most dangerous and physically demanding part of an Annapurna climb.

“I summited Everest in 2023 and Annapurna is much, much harder,” Samiur Rashid of the UK told ExplorersWeb. “I consider myself to be really fit, but Annapurna took all my strength. Some vertical sections I thought I would not be able to do. It was a very hard climb.”

Irina Galay told ExplorersWeb: “We arrived at Camp 3, rested a bit, and began our ascent at 6:30 pm on April 11. We reached Camp 4 at 8:00 pm and saw a team already leaving to fix the ropes…After a brief rest, we followed them.”

Galay, who resorted to bottled oxygen from Camp 3, reported that fresh snow loaded the upper sections. “The journey to Annapurna’s summit is very long, and waiting sometimes for more than an hour [as the rope fixers did their work] made it even longer.”

Frostbite

“Looking back, I think that was when I started getting frostbitten,” Rashid said. “When you move, you feel the cold but your blood is circulating. But that constant stopping and waiting numbed our limbs.”

Recalls Galay: “After nine hours, we were only at 7,300m and it was bitterly cold. I saw people starting to pass each other, but it made no sense because we were all just standing there. Some wanted to be first, others had different desires, some sherpas on short leashes began pulling their clients forward. I realized it made no sense to stand around. I moved forward to the fixing team and started helping them.”

No-rope section

“By the time I followed them,” Galay continued, “they began traversing to the right, and there was no rope. [But] the state of the snow was quite good, and it was possible to move without a rope, but very carefully, with an ice axe. It was dangerous, but all Annapurna is dangerous.”

Galay says it took 40 minutes for the whole line to pass the traverse section without ropes.

On reaching the summit, Galay was right behind two rope fixers and two other Nepalese.

“They asked me to wait a bit so they could secure everything, then told me I could approach,” she said. “They clipped my backpack to the station with a carabiner, and I sat there. Following me, this 18-year-old guy [Nima Rinji Sherpa] was climbing without oxygen and still keeping my pace. He is very strong! I tried to let him go ahead, but he said, ‘No, no, you go first, you deserve it.’ After me, he was the next one up.”

Nima Rinji was actually just 17 when he summited Annapurna and is well on his way to becoming the youngest 14×8,000m summiter ever. Annapurna was his 11th peak. He is competing for the same distinction with slightly older climbers such as Shehroze Kashif of Pakistan and Adrianna Brownlee of the UK.

In addition to Galay and Dorchi Sherpa, the summiters that day, as reported by Sveen Summit Treks, were Chhang Dawa Sherpa (the expedition leader), the young Nima Rinji Sherpa (no-O2), Pasang Nurbu Sherpa, Ngima Tashi Sherpa, Mingtemba Sherpa, Pasang Sherpa, Pemba Thenduk Sherpa, Lakpa Temba Sherpa, and Manish Maharjan. International climbers included Klara Kolouchova of the Czech Republic, Iryna Karagan of Ukraine, and Samiur Rashid of the UK.

Close call on the way down

Galay said she spent about an hour on the summit, then started down. She negotiated the area without ropes very carefully.

“On the way, I saw sherpas helping a guy who was in bad shape,” said Galay. “I only found out later it was Pavel [Pavlo Sydorenko], another Ukrainian.”

Sydorenko never reached the summit. He collapsed on the way up, shortly above Camp 4.

“I am not sure if his supporting sherpa was with him, but he spent a lot of time lying on the ground,” Rashid said.

Eventually, sherpas on their way down from the summit lent him a hand. Klara Kolouchova found him at 6 pm, some 200m above Camp 4, as she descended from the summit.

Ukrainian nearly dies

Said Kolouchova:

He was being pulled down on a rope by three sherpas, one of whom was my sherpa Chhepal. When I got to them, Pavlo was hardly communicating (if at all). He was not able to move and just pointed to his chest, signalling he had difficulty breathing. I had an emergency adrenaline pen on me, which I applied to his thigh.

Soon after, he managed to get on his feet, and with support, he could slowly progress on his own toward C4. I made sure he was secured by a short rope to another sherpa and I continued down to C4.

Once there, I talked with Allie Pepper, who was at C4 getting ready for her summit push. She agreed to give Pavlo a shot of dexamethasone as soon as he reached C4. Once we agreed on this, I continued down to C3 for the night.

Early the next morning, heli rescue picked up Pavlo and Iryna [Karagan] and took them down to BC. I believe the application of adrenaline together with dexamethasone saved his life.

Both Kolouchova and Rashid told ExplorersWeb that Iryna Karagan was extremely tired and needed lots of support on the way down.

“I do not think there was a competition among the two Ukrainian ladies [Irina Galay and Iryna Karagan] to be the first on top, because it was clear that one was much stronger than the other,” Rashid said. “I climbed with Galay most of the time, and she is extremely strong and skilled.”

Galay and Mingma Dorchi reached Camp 3 at 6 pm, as night fell. Then they went to sleep.

From Camp 3 to Base Camp — or to Kathmandu

We asked Irina Galay what happened when she woke up on the following morning (April 13), and this is what she replied:

“When I woke up in Camp 3 after the summit, I realized that many people in Camp 3 were preparing to be evacuated by helicopter. One of them was Iryna Karagan. I told her not to do it because the key section of the route is between Camp 2 and Camp 3, and if someone can’t handle it, I don’t think the summit should be considered fully achieved. But she said she felt very ill and wanted to be with Pavel. Another Nepali from Camp 3 also flew out by helicopter.”

Kolouchova and Rashid confirmed Karagan jumped in the helicopter and left. They couldn’t tell whether she was too tired to continue down. Korouchova said Karagan looked exhausted but not sick.

“When we think we can’t go any further, it is incredible how much more the human body can take,” Rashid said. “I was not feeling 100% going down either, and I was offered the lift as well. My sherpa insisted I should take the helicopter, but I strongly refused.”

Very strongly, indeed. “I’d rather die than be airlifted,” Rashid reportedly told the sherpa. “I am extremely adamant on that point — a valid climb starts and ends in Base Camp, period,” he explained. “I tell that to every climber. A summit with part of the way done in a helicopter is not a summit.”

Rashid and Galay said some Nepalese were also airlifted but they don’t remember who they were. We have asked Seven Summit Treks’ PR spokesperson if any member of their team was airlifted from Camp 3. We are awaiting a reply.

ExplorersWeb has also asked Iryna Karagan for her side of the story, as well as Allie Pepper. On April 13, Pepper was preparing for her summit push. We are still waiting for their reply.

Rescue or shortcut?

Last year, a large number of climbers were evacuated from Annapurna’s high camps. There were several emergency evacuations (such as Jonathan Lamy with frostbite and Baljeet Kaur after spending two days lost at altitude). In addition, one climber died (Noel Hanna), and five more (Arjun Vajpai, Naila Kiani, Shehroze Kashif, Dawa Nurbu Sherpa, and Lakpa Sherpa) were airlifted from Camp 3 because the conditions on the section below them were considered risky. These evacuations created a heated debate on whether such summits should be considered valid for the climbers’ 14×8,000m lists.

Obviously, all expedition leaders do as much as they can to get a sick or injured climber safely down. The debate is not on whether to airlift but how such an event affects a climber’s summit claim.

If the reason is an unacceptable risk, that is a personal decision and should be up to each person, as long as they are transparent about it. But in that case, many would argue that the final result should be considered an incomplete ascent, just as it would have been if dangerous conditions on the mountain had forced a retreat. When the reason is to avoid any possible risk and to return to Base Camp or to town quickly and comfortably, the climb has not only been incomplete but unethical from a mountaineering point of view.

A regular practice

Yet — and this is the most surprising fact — such airlifts are not only an open secret, but are becoming a regular procedure for those willing to use it and able to pay for it. Rashid saw this on Everest in 2023.

“Climbers take a helicopter from Camp 2 because they are tired and want to avoid the Khumbu Icefall,” he said. “Some climbers also take the helicopter on the way up and start their summit push from there.”

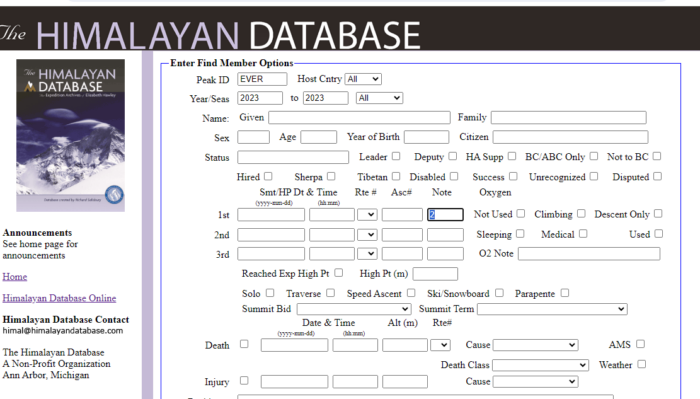

The Himalayan Database notes 23 (!) climbers who were “aviation-assisted” last year going down from some point above Base Camp on Everest. Below, how to find such data yourself:

“Honestly, it’s strange for me because we climb to complete the journey, up and down,” Irina Galay said. “If you can descend, you descend. If you can’t, it’s a rescue, an evacuation. [Anything else] is absurd and needs to be regulated.”

At ExplorersWeb, we believe it is common sense that a helicopter shortcut is not acceptable for any summit record. But the fact is, Nepal’s authorities regularly validate such summits.

We asked both The Himalayan Database and 8000ers.com for their take on this:

Statistics: noted, not canceled

“We recognize the summit with an “aviation-assisted” note,” said Billi Bierling of The Himalayan Database.

She said that several Annapurna climbers had airlifts from Camp 4 last year. Yet climbs with such asterisks are not easy to find, since they are not included in the season lists. (This writer needed nearly an hour of the ever-patient Bierling’s time to find that information.)

Moreover, not every helicopter user shares such details with The Himalayan Database. “This data is not very reliable since helicopter descents are often/usually not reported,” their Technical Director, Richard Salisbury, noted.

Eberhard Jurgalski of 8000ers.com says the frequent use of helicopters in climbs should always be noted. Soon, he will require this information from climbers in a new, enlarged version of summit lists he is preparing.

These future tables will record various “styles,” including the use of oxygen, ropes, supporting sherpas, camps pitched by others, etc. And, of course, whether the climber took a helicopter anywhere along the way. It would also include paragliding and BASE jump descents.

Yet the question remains: Is a climb done partially in a helicopter a valid summit? For Jurgalski, the style in this era of commercial climbing only matters when the climber is trying to break or establish a record. “In that case, the summit will not be considered valid for the record,” he says.

Nowadays, most clients are not doing just one peak, they intend to climb several or all the 14×8,000’ers. Likewise, sherpa guides use valid summits as a positive tick on their resumés.

A terrifying section

“When you are on your way up, the summit fills your mind completely,” Rashid said. “On the way down, I can only think of my family, and of returning to them as soon as possible.”

Galay points out how life-threatening the section between Camp 3 and Camp 2 is.

“There’s a gully where avalanches occur every 20 minutes,” she says. “I personally saw and heard them, I know how terrifying they are. I was so scared when I was there that my legs were shaking. But I kept walking, while someone else took a helicopter? It’s not right. And why do we then receive the same certificates? I find this extremely unfair.”

“After we started our descent,” explained Galay, “Klara [Kolouchova], Sami [Samiur Rashid], and I successfully reached Base Camp without seeing anyone else coming down except one Spanish climber. [This was] David Nosas, who turned around at 7,400m. He walked down too.”

A high toll

For Samiur Rashid, descending on his own took a high toll. He reached Base Camp with frostbitten toes.

“I had big plans for this year,” he admitted. “I wanted to climb other peaks in Nepal and then go to Pakistan, but all that’s over now. My right foot is badly frostbitten, and I am back home in London with a long recovery ahead.”

Rashid said that back in Camp 3 when he was offered the airlift, he did not know about the frostbite. What would he have done had he known?

“Even if I had known I was frostbitten, I would have tried to wrap and warm my feet and continued down on foot [with my sherpa],” he said.

So what now?

As with other sensitive issues concerning Himalayan climbing these days, the problem is that malpractice by a few affects the entire community. The code of omertà that outfitters and their clients follow does not help. Climbers who play by the rules are frustrated to see their achievements compared to others whose successes depend partly on mechanized shortcuts.

But when asked about it, they don’t want to be whistleblowers, or else they stay silent to remain on good terms with other climbers and outfitters. Ultimately, though, the truth surfaces and spoils the credibility of the entire industry.

Norrdine Nouar of Germany summited Annapurna without oxygen or personal sherpa support on April 14, together with Flor Cuenca. Luckily, he acclimatized before trekking to Base Camp by climbing up and down Thorong La for several days.

He would have liked to have had more time on Annapurna but understands that self-sufficient, no-O2 climbers are not the best clients for the expedition business. At the same time, he says that 8,000m mountaineering is at a critical juncture. Its image and reputation are in a terrible state, he says. Nouar goes on:

Every climber [should ask themselves] why they climb a particular mountain, and why in the style they choose. Do they love the mountain and want a real experience or challenge with the mountain? Or do they want an easy summit, a nice summit picture, and a nice story to impress their friends and relatives at the dining table?

Right now the world thinks that Everest climbers are just an idiotic bunch of rich egos, who want to buy the summit with the excessive help of sherpas.

These are harsh and unpleasant questions, but we mountaineers need to ask them and be honest about our answers, or the sport will just continue to get worse.

Nouar is currently on his way to Everest, where he will also climb without supplementary oxygen and will carry his tent and all his own gear and supplies.

It is up to climbers whether they favor transparency and set clear differences on climbing styles, or mind their own business. Taking a helicopter from a mountain is a personal choice. But keeping quiet about it and claiming goals while not playing by the same rules as others should not be an option.

The post Annapurna Sets a Disappointing New Normal: Helicopter Taxis appeared first on Explorersweb.