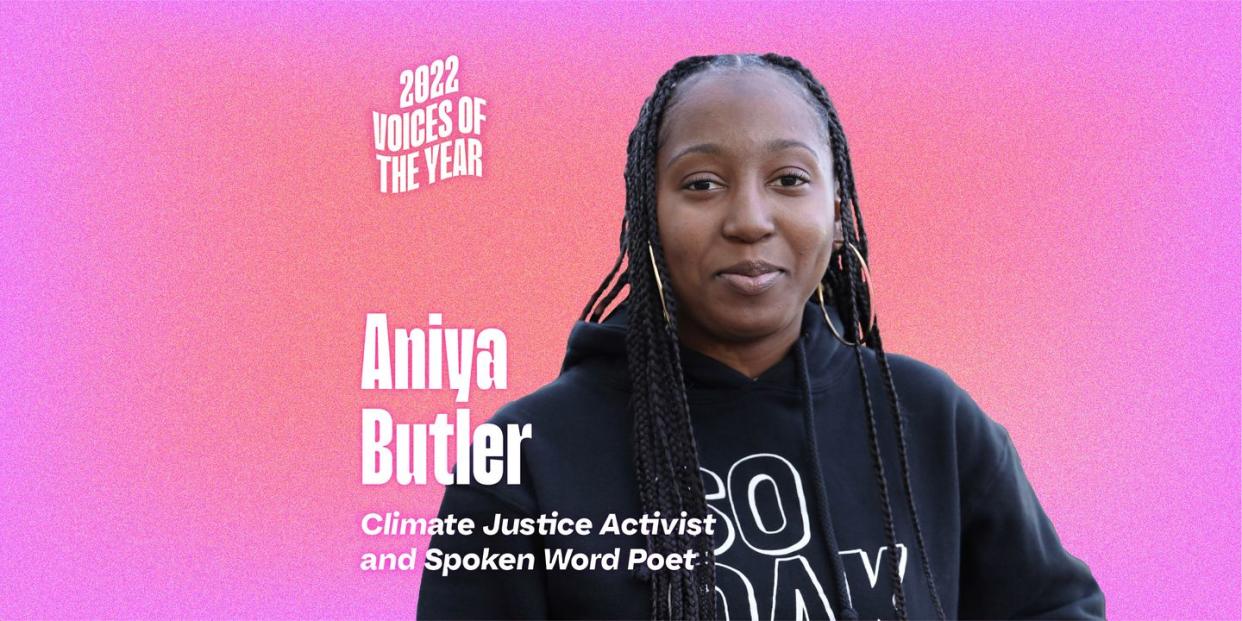

Aniya Butler Uses Spoken Word Poetry to Fight Environmental Racism and Climate Change

Many teens are acutely aware of the current state of our planet, thanks to what can seem like non-stop news and social media coverage. But for one girl, in particular, the recent onslaught of climate change-induced issues inspired her to spring into action and set some major positive change in motion.

Meet Aniya Butler — the California native is a spoken word artist who’s been honing her craft since she was eight years old. The now 16-year-old is an advocate with Youth vs. Apocalypse (YVA), an organization of young climate justice activists working together to fight for the planet. Aniya uses her writing to draw attention to some of the most pressing issues that Gen Z faces today. She's a force to be reckoned with within the climate justice space, and she's hell-bent on demanding both climate and racial justice through action and art.

Aniya's poetry initially focused on the police brutality that her Oakland, California community was experiencing, but she explains that the marriage of anti-racist activism and advocating for environmental change was inevitable due to how closely the two are interconnected. One of Aniya's poems, entitled Wide Eyed Black Girl, was written during the Summer of 2020 from the perspective of George Floyd's daughter. The following is a short excerpt of her powerful writing:

"I am angry

That we are too busy fighting each other to recognize

That we are not the ones who cause these crises

We are not the ones investing into institutions of destruction

We are following the systems that put us here

the ones that are corrupt

It’s time for them to listen to our instructions."

When Aniya speaks about the importance of an intersectional understanding of climate justice, police brutality, and environmental racism, it's clear that she has an intimate understanding of the present-day effects of what she fights against. When Aniya speaks, she leads with art and poetry to talk about the weighty and the distorted. When Aniya speaks, people listen. And she's only just getting started.

How did you get started in the climate justice space?

Aniya Butler: I was never really connected to the climate justice movement. It was around eighth grade for me when I got involved. I’m a poet, and most of my poetry focused on brutality and police violence toward Black people. I knew about climate change, but I just never felt like that's where my energy needed to be contributed to in the movement because it wasn't portrayed to me as this thing that was impacting people now — as a thing that was impacting like my own community right now through pollution, lack of accessibility to clean water, and so many different factors of environmental racism. I just never thought it was something that was impacting my people.

But once I learned more about intersectionality through Youth vs. Apocalypse, a week before the International Climate Strike Day of 2019, September 20th, that's when I was like, “This is where I want my energy to be contributed to.” And so I got involved with organizing and the climate justice movement.

Tell us more about what environmental racism is.

AB: Environmental racism is how different negative environmental issues are disproportionately impacting people based on their race. I know in my community, areas of pollution are mostly around the highest minority-concentrated areas. Our highest asthma rates, along with other respiratory diseases, come from people who are low income, people who are Black and Brown. Looking at the different effects of climate change and how it is impacting people, you can see that it's really detrimentally, [and] disproportionately impacting BIPOC people compared to other communities.

You got started with anti-racism activism before going into environmental activism. How did you begin at such a young age?

AB: I think it's because Oakland, where I'm from, is home to so many different revolutionary movements and contributions. Just being around this community that is centered around protecting each other and fighting for justice and being around so many different people, especially youth. Also, using art as a way to advocate for change and justice is what really influenced me into getting started so soon. That was my atmosphere. It was what I saw, and what I embraced. I think having that community really allowed me to step into activism and organizing at a young age.

Tell us more about how you use art and spoken word poetry as activism.

AB: Poetry and spoken word are the roots and foundation of all of my work as an activist, organizer, and advocate. I started to write when I was eight and then I started to perform when I was 10, mostly due to my mom. [Laughs.] But I think because all of these issues are so difficult, I feel like poetry allows me to be my most honest and truthful self — to be radical about the things that we're talking about. It allows me to have my own opinion about what I want to see in the world for myself, and what I want to see for my community. At the same time, it’s a way for me to try to process these things that I'm up against. Poetry is a way for me to advocate for change, but it's also for my survival. It keeps me sane. It helps me try to understand these things that I’m working with so many people to go up against.

Do you have a favorite piece that you’ve performed?

AB: I have different favorite poems based off of what point of my life I was at when I wrote them. I wrote this poem during the pandemic called “Wide-Eyed Black Girl,” but it started as a poem called “Wide-Eyed Black Boy.” It was a couple stanzas that I had written during a creative workshop. But then I had an interview where they asked me to act like I was reading something from a journal, so I opened up to that page and as I was reading it, I was like, “Well, I can like definitely use this.”

I was working with the Hip-Hop and Climate Justice team and another poet at the time, and we were talking about different pieces that we were working on. The poet suggested that I change the title to “Wide-Eyed Black Girl” to have the poem be through the eyes of George Floyd's daughter during the pandemic. I was like, “That sounds really cool.” As I continue to write it, I realized these things can be applicable to so many young Black girls across the world, including myself. And I think it’s one of my favorite poems because of how much it tackles things at the root — it talks about intersectionality and how all these different issues that people are experiencing are connected, and how the climate crisis just exacerbates them. That was probably one of my favorite pieces that I've written.

What accomplishment are you most proud of achieving?

AB: We did an action on September 23rd focused on No Coal in Oakland. Our overall messaging was saying no to coal and the coal terminal that’s being threatened to be built in the community of West Oakland. We were saying no to coal but also no to all forms of violence because we recognize that [there are] so many different forms of violence in Oakland from police violence to gentrification to sexual violence. We wanted to really try to tackle all those things while also saying yes to life and yes to all systems that enabled thriving, unity, and us taking care of each other. I was the lead organizer on that and it was one of the first actions in Oakland for YVA.

It was powerful for me to be able to hold the space for so many youth in Oakland and to see how many youth came to push themselves outside of their comfort zone. I think at least a thousand students were there. We rallied at Oscar Grant Plaza in Oakland and then went on a march downtown. We stopped at the police department and then went on a loop around back to Oscar Grant Plaza. I was also on crutches, but it was cool to see how many youth were stepping into different forms of leadership — stepping up to the mic and stepping up to lead chants without my support because I was injured. Seeing them take control of the moment and feel confident enough to do that made me really proud.

How do you feel like you've grown since you first got involved in activism?

AB: I got involved with organizing when I was 13 and now I'm 16. I feel like I’ve really grown in learning about the issues and how they’re connected, just learning so many other perspectives and how those different perspectives can be used to uplift the other — to advocate against the root of things, the systems of capitalism, colonialism, racism, patriarchy, et cetera. Getting to connect with so many different communities and learn their stories and their struggles and how they connect to mine. And I think I've grown in knowing where I want my energy to be contributed, which is really helping my community.

Have you thought about what you want to pursue for your future career? Does it involve activism?

AB: Since preschool, I’ve wanted to be a doctor. I still generally have [an] interest in the medical field, but the work that I'm doing now is something that I really want to do. I hope that I won’t have to be a direct organizer for my career, I hope things are better by then, but I definitely want to do work in my community because I know that there's still a lot of work to repair the damage that has been done. I want to be in some type of job that allows me to help those communities heal, and support others in their activism.

YVA is youth-led and it's really about youth doing things with amazing adult supporters who help us. I think I would really want to step into that role. I like using my experience to help others who really don't have the accessibility to all the things that I did, to learn about what they want to do and how I can support them.

How do you balance school, activism, leadership roles, and writing?

AB: I’m definitely figuring that out. Figuring out a schedule that’s healthy for me has probably been one of my greatest challenges this year. I do a lot of work with YVA, plus I have schoolwork and I hold leadership positions at school. And then spending time with family and sleeping and finding time to take care of myself — I definitely don't have it all down. But hopefully, I will get it figured out soon.

Speaking of things that are hard to figure out, what would you say is a challenge that you've learned from the most?

AB: Having the motivation to keep going. I help with a lot of actions and events — we’re putting all this time into actions and reaching out to people and building community and making tangible change. We've been successful in that. But just knowing that we have the funding to create change for a healthy planet and that our leaders are just deciding not to help because it doesn't maximize their profit is really frustrating and challenging to think about.

It’s like, how did we end up here? The issue is very complex, but people are asking for things that aren’t crazy — they are asking for basic human needs. Knowing that it's so difficult for people to get them is very challenging. And knowing that climate change is an issue that’s a problem right now and that hundreds of communities have been impacted by it — knowing that they're receiving no help and that climate change is only just now getting more focus because it's now impacting more privileged communities is also really frustrating. It’s taken us so long to put focus on it and even longer to actually start creating some change. We’re doing better, but just knowing that we can still do better than where we're at is challenging.

What inspires you to keep advocating for other people?

AB: The people that I get to work with. Youth. Seeing their dedication and knowing that they're really giving up a part of their lives that could be used to do regular teenager things and they're using it to fight for the planet. I think that really gives me hope because it just shows me that I'm not the only person who thinks like this, I'm not alone in the movement. And those adults who specifically support youth activism and organizing — they’re inviting us in as collaborators rather than treating us as people who are under them. People who are involved in this movement and supporting youth in this movement give me hope to keep going because I see that they're dedicating their time, so it just gives me more energy to dedicate my time.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Photo Credit: Mario Capitelli. Design by Yoora Kim.

You Might Also Like