40 of America's Most Impressive Feats of Engineering

When engineers figured out how to force the Chicago River to flow in a different direction, that's a feat. When they spanned the Pacific Ocean in San Francisco with the Golden Gate Bridge, that's a feat. Or even when engineers carved precise measurements into hillsides with rudimentary tools—whether for a road or a monument—that's a feat. Explore 40 of the most impressive engineering feats in American history.

When work wrapped up in 1965 on the Gateway to the West Arch as part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the St. Louis landmark included a tram ride to the top that required a new elevator-style roller coaster. With a structure 630 feet high and 630 feet wide at its base, the construction required both sides to start at the bottom and meet at the top with less than half a millimeter of error allowed.

While the entirety of the national Interstate Highway System is a marvel, the intricacies of I-80 offer a glimpse at what makes the system so historic. Spanning 11 states in total, it starts with a crossing of the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, crosses the Bonneville Salt Flats near the Great Salt Lake, reaches 8,000 feet above sea level in Wyoming, and has a 72-mile stretch—the longest of all interstates—of virtually straight run outside of Lincoln, Nebraska. The freeway teases within a few miles of Chicago and Cleveland on its way to terminating four miles shy of New York City.

With sewage flowing from Chicago into Lake Michigan, a drinking water source for the growing region, the city was facing a health crisis due to waterborne diseases. However, engineers discovered they could dig the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal to help reverse the river's flow, moving polluted water away from the lake and sending it towards St. Louis.

Mount Rushmore was crafted from raw materials, with workers carving 60-foot-tall heads of former U.S. presidents into the granite cliffs of South Dakota’s Black Hills. A team of about 400 took roughly 14 years to complete the task, with no loss of life. During the process, workers primarily used dynamite to clear away 450,000 tons of rock, before carving the faces using facing bits and jackhammers.

The San Francisco Bay Area is lucky enough to have two internationally renowned bridges. The newer Bay Bridge East Span, a $6.4 billion project, replaced a seismically unstable bridge. It has the world's longest self-anchored suspension span at 2,047-feet-long and is anchored by a single 525-foot-tall tower that holds a main cable containing 17,399 steel wire strands. The single 2.6-foot-diameter main cable loops around the roadway, held aloft the tower that supports 90 percent of the bridge's weight, giving engineers a solution to placing one of the world’s widest bridges in the tricky soil conditions of the Bay Area.

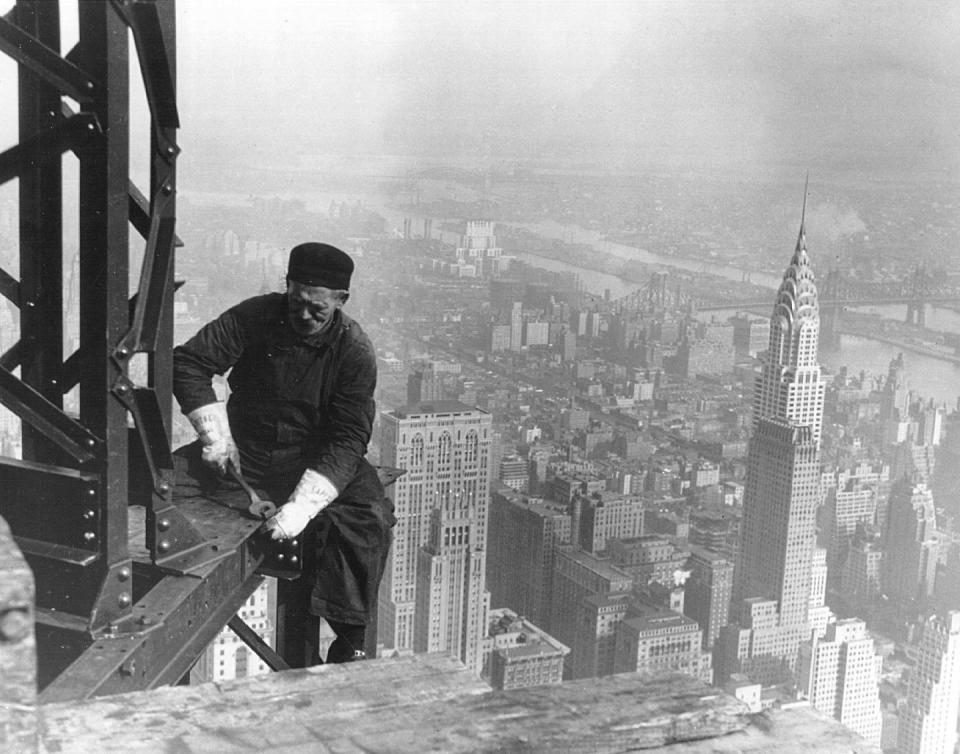

With apologies to the 1930s-opened Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building in Manhattan stands alone as one of the most influential skyscrapers in world history. Opened in 1931 at 102 stories tall and 1,250 feet tall—passing the Chrysler Building's 1,046 feet—and standing as the world’s tallest for over 40 years, the Empire State Building uses a steel frame clad in 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana limestone and granite to create a structure that proved iconic both for engineers and New York residents.

For 242 miles, the Colorado River Aqueduct siphons water from the Colorado River, using canals, tunnels, and pumps to move the water toward the parched lands of Southern California. The aqueduct was opened in 1939 and used various systems to continually move water up and over mountains to the places not naturally served by rivers, making it possible for cities like Los Angeles and San Diego to grow.

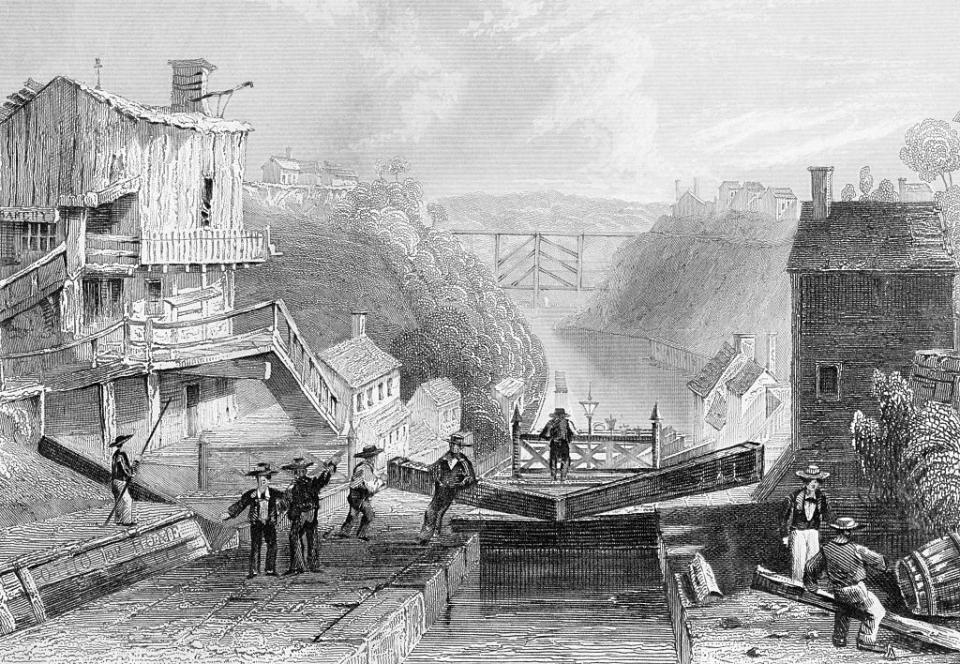

The 363-mile-long Erie Canal connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Great Lakes. The eight-year project wrapped up in 1825 and uses 83 locks. To make it work, engineers needed to use gunpowder for blasting—there was no dynamite yet—and create cement capable of setting underwater.

Neil Armstrong took it to the moon in 1969, using that 7.6 million pounds of thrust during launch to push this 363-foot-tall rocket toward new space heights for the United States. The Saturn was designed in Huntsville, Alabama with Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and IBM sharing know-how on a rocket that powered Apollo missions aplenty. Virtually every aspect of the rocket was bigger, heavier, and more powerful than anything previously created.

The four-year project to span the Golden Gate strait and connect San Francisco to Marin County culminated in what was the world's longest (4,200 feet) and tallest suspension bridge when this Bay Area landmark opened in 1937. The bridge kept those records until the 1960s. The Joseph Strauss design required thousands of hand calculations of every rivet and mooring location and needed 80,000 miles of steel cable spun on site within 14 months to ensure 27 feet of lateral bend in the bridge.

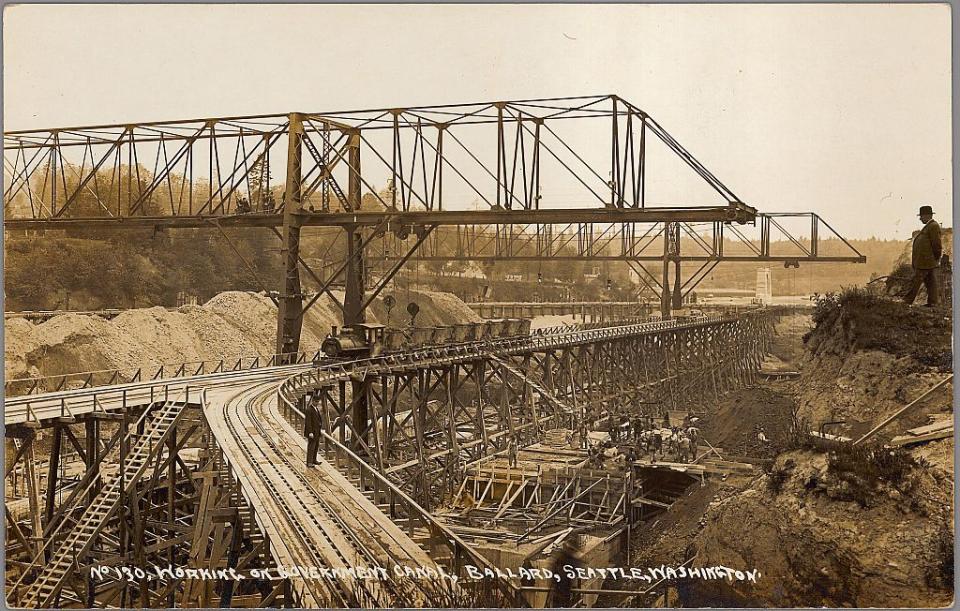

The most used locks in the United States carry everything from kayaks to barges, while connecting the salt water from the Puget Sound with the fresh water of Lake Washington and Lake Union. Located north of Seattle's famed Space Needle and known locally as the Ballard Locks, the complex includes two locks (one 30 by 150 feet and the other 80 by 825 feet) and was made with concrete instead of wood for longevity. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operated locked opened in 1917.

While not finished until 1959—after the death of both the museum’s namesake and the architect—Frank Lloyd Wright embraced a differing form than common in Manhattan. The cylindrical stack grows wider as it spirals upward toward a glass ceiling. Wright claimed his design would "make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the world of art before.” The Wisconsin native, known for incorporating form into residential design, gave architects liberty to move away from the rectangular with his free-flowing Guggenheim.

At 210 feet tall, the Glines Canyon Dam on Washington's Elwha River was the largest dam demolition ever. Built in 1927, it took a combination of excavators chipping away at the top of the dam layer by layer and then some good old detonation to remove it for good in 2014. As crews reached the lower portion of the concrete structure, they sped up the removal process by bringing in explosives, using a series of blasts to finish off the dam before then completely engineering a revitalization of the river habitat that had been lost behind the dam for nearly 90 years.

The world's longest floating bridge was upstaged in April 2016 when the brand-new State Route 520 Floating Bridge replaced it. The new span, which runs just a few feet to the north of the old Seattle bridge, spans 7,710 feet across Lake Washington and is six vehicle lanes wide. It uses 77 concrete pontoons as the foundation; the weight of the water displaced by the pontoons equals the weight of the structure, allowing it to float. The roadway is elevated 20 feet above the water and a total of 58 anchors secure the bridge.

Stones, opened in September 2016, goes the deepest of any offshore structure by reaching a staggering 9,500 feet underwater. Located in the Gulf of Mexico off the shores of New Orleans, the above-water structure was built in Singapore before making the cross-ocean trip to its current location, where it ties to wells. Stones uses a flexible "steel lazy wave riser" to carry oil and gas to the top, with the bend in the piping absorbing the motion of the structure.

Built between 1931 and 1935, the Art Deco-detailed dam was the most expensive engineering project in the U.S. at the time and became the tallest dam in the country at 726 feet tall. Today, it's still the second-tallest dam and the tallest concrete dam. It required 91.8 billion cubic feet of concrete to create the arch-gravity dam with a 600-foot-wide base, weighing 6.6 million tons in total.

It may have taken 14 years to build, but when the Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883 to connect Manhattan and Brooklyn, the single span of 1,595 feet suspended by four cables was a world’s first. The 15.5-inch diameter cables comprised of 5,434 parallel galvanized steel wires represented the first time steel was used in a suspension bridge scenario. The towers, built of limestone, granite, and cement, stand iconic, while the bridge itself used steel—instead of iron—to reduce dead weight.

The 605-foot-tall Space Needle in downtown Seattle offered a futuristic take on life when built to commemorate the 1962 World’s Fair. The 9,550-ton structure stretches 138 feet wide—and one inch wider on hot days, as the building expands slightly—and offers a defining symbol for the Emerald City. The foundation, though, reaches 30 feet down with 72 bolts, meaning that five feet above ground level is the needle's center of gravity, ensuring stability.

Using multiple structural systems within a single building offered increased stability—and the ability to go taller. Architect Minoru Yamasaki used the concept of multiple columns of "tubes" developed by Fazlur Khan to allow stability at even more magnificent heights than achieved before. The World Trade Center opened in 1973 at 1,368 feet in height and was the first real example of the new style of design. The towers were the tallest in the world for just a smidgen of time, until the Sears Tower opened in Chicago. Tragically terrorized in 2011, the new World Trade Center building eclipses the original in height.

Over 100 years old, this copper mine includes a 2.5-mile-wide pit in the Oquirrh Mountains southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah. Considered the largest man-made excavation, the mine dips nearly three-quarters of a mile down and covers 1,900 acres. First opened in 1906, the mine is still open and is a National Historic Landmark with a visitor center for folks who want to come and gawk at the hole in the ground that's required intricate planning throughout its decades of use.

The Grand Coulee Dam may not be the tallest at 550 feet high, but the seriousness of this 1942-built dam outside of Spokane, Washington comes from its sheer size. With over 12 million cubic yards of concrete, the Ground Coulee Dam spans the Columbia River for nearly a full mile, backing up Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake reservoir nearly to Canada. Depending on your preferred analogy, the Grand Coulee Dam contains enough concrete to build a highway from Miami to Seattle or a sidewalk around the equator—twice. But the dam doesn't just sit there. With 21 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, Grand Coulee creates the most hydroelectric power of any dam in the U.S.

At 707 feet tall, the Zaha Hadid-designed tower in Miami has become known as Scorpion Tower because of an aesthetically noticeable exoskeleton that also acts as a unique structural support to allow the elimination of interior columns. The twisting support columns create a signature curve in the Miami tower, but also brace the building from the outside. To ensure both structural soundness and a pleasing form, starting on the 15th floor columns were formed with glass fiber reinforced concrete.

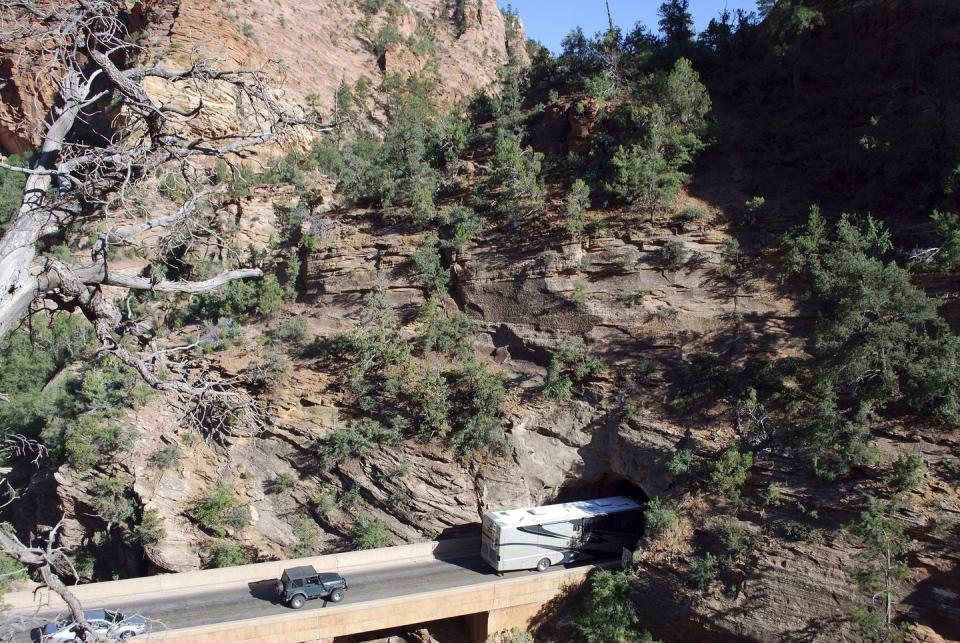

Nearly 100 years ago, the United States attempted to make its national parks more accessible, sometimes a difficult proposition in then-remote areas. Part of that effort was a 24-mile-long highway through Zion, which includes the 1.1 mile Zion-Mount Carmel Tunnel. Opened in July 1930, it was the longest tunnel of its type in the country at the time and created direct access to Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon from Zion National Park.

But it wasn’t the easiest tunnel to construct. Working in relatively soft sandstone, workers decided to create windows in the sides of the cliffs to remove the stone as they went. The softness also required concrete reinforcement and a full-time electronic monitoring system that alerts park officials to any shift in the stone. Now, too small to handle two-way traffic of oversized modern vehicles, the typically one-way tunnel is managed during heavy tourist times, sometimes requiring long waits to enter.

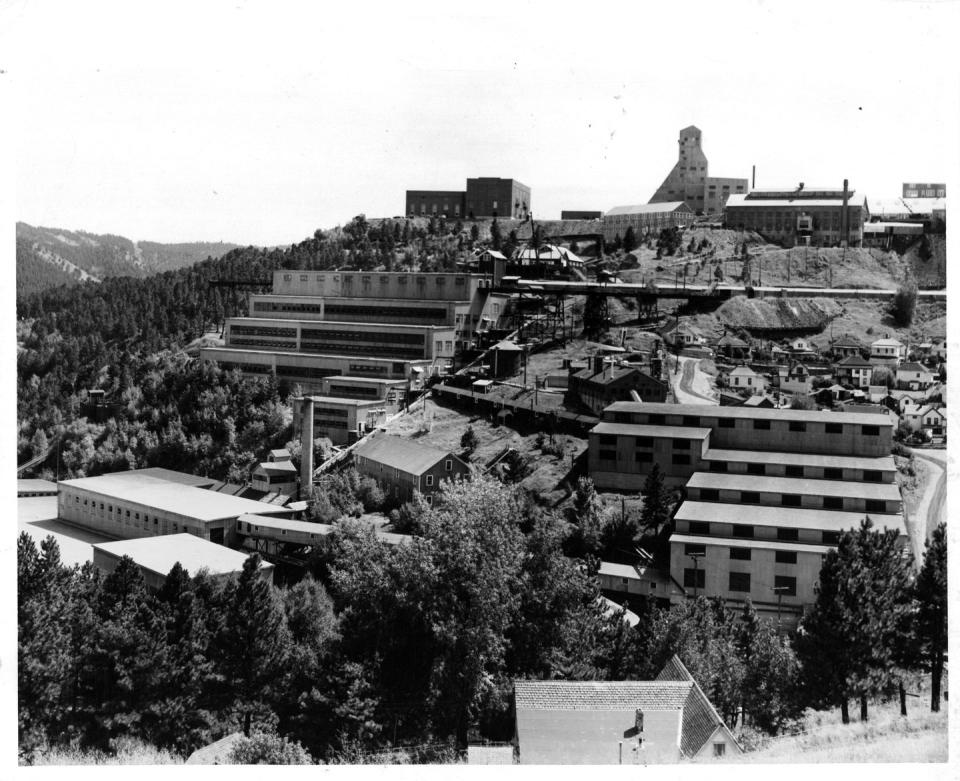

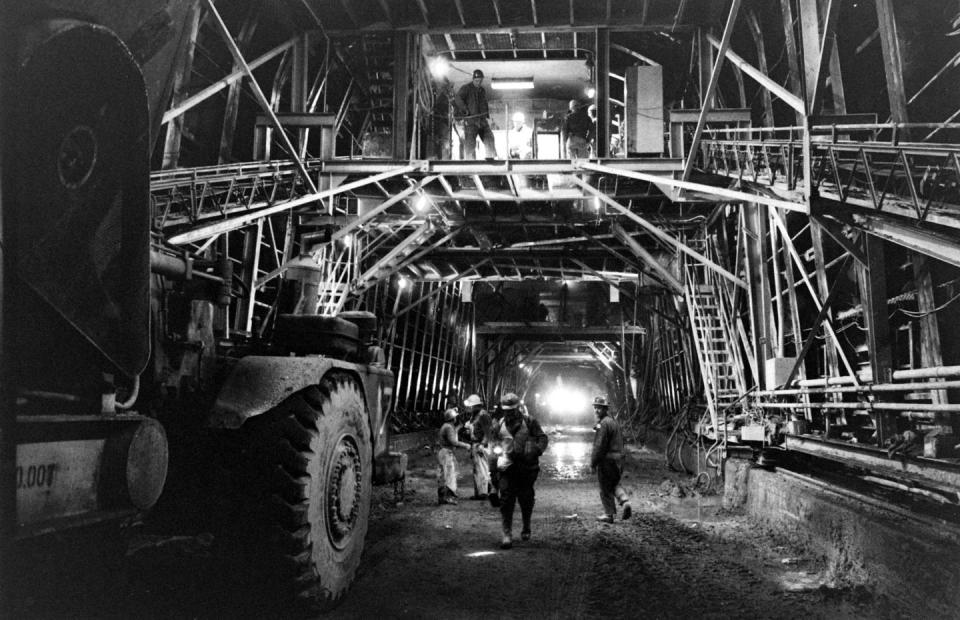

What was once the Homestake Gold Mine (the continent’s largest and deepest gold mine) is now the Sanford Lab. It's located nearly 5,000 feet below ground—and there's room for more, as the mine dips 8,000 feet below the surface. Stretching to the equivalent of more than six Empire State Buildings, the lab at 4,850 feet deep allows the study of dark matter, all shielded from interfering cosmic rays.

Opened as the Sears Tower in 1973, the 110-story, 1,450-foot-tall structure outshined New York's World Trade Center as the tallest in the world. The Sears Tower, now known as the Willis Tower, followed Fazlur Khan's structural tube design (he was also the architect on this project), allowing for taller skyscrapers with more stability, while not relying on them tapering at the top. Khan's development gave the world one of its tallest structures for decades—the Sears Tower was the world's tallest until 1998—and provided the backbone for even further development.

The 4.2 million square feet of floor space and 472 million cubic feet of volume in Boeing’s main manufacturing facility north of Seattle in Everett, Washington offers plenty of space for airplanes. Covering nearly 100 acres while churning out four airplane types, the facility includes a museum, theater, restaurants, and a store. The 1966-built facility features 2.33 miles of pedestrian tunnels underneath the factory floor, to help workers get around without getting in the way of airplane production.

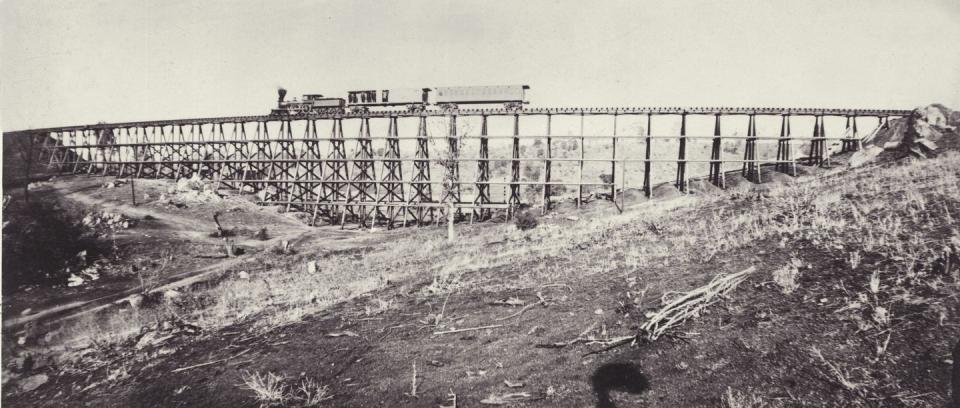

The Central Pacific and Union Pacific had the task of connecting the two coasts. Thanks to migrant laborers—many lost during the six-year effort—working largely by hand, the project was completed in 1869. But it wasn’t without incredibly strenuous efforts to burrow through mountains and withstand harsh environments.

One of the most picturesque mountain locations in the country deserved a way to be seen by more—or so those behind the 51-mile Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park thought. The three-decade-long project included surveyors using ropes to dangle off cliffs for measurements and tunnel excavation done by hand. The road officially opened in 1933, crosses the Continental Divide, and reaches an elevation of 6,646 feet.

Considered one of the craziest rollercoasters in the nation, Kingda Ka at Six Flags Great Adventure in New Jersey hits 128 miles per hour in just 3.5 seconds, and features a 270-degree spiral. The fastest coaster in the country may not last a full minute, but with its height—the tallest in the world at 456 feet—Kingda Ka creates a wild ride unlike any other.

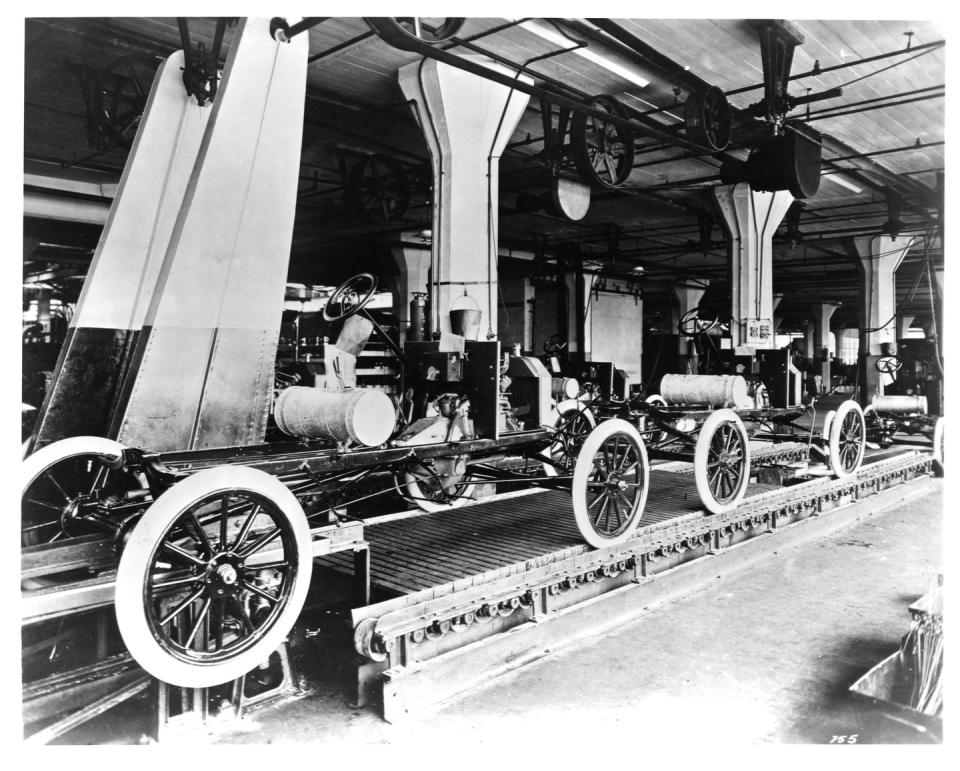

The Model T from Henry Ford created a more affordable vehicle, opening up a new style of transportation to more people. But the process of making the Model T, with the first moving assembly line, also revolutionized manufacturing processes and reduced prices for the self-starting Model T.

At 11,013 feet, Colorado claims it has the highest vehicle tunnel in the world. Traversing the Continental Divide, the Eisenhower Tunnel complex moves through the Arapaho National Forest with two twin bores, both stretching just feet shy of 1.7 miles and at distances of 115 to 230 feet apart. Opened in the 1970s, the average grade of both tunnels is 1.64 percent from east to west, but approach grades can reach 7 percent. Each tunnel comes in at 40 feet wide and 48 feet tall, but an exhaust and supply air system located above in the ceiling creates a different visual for drivers.

Revamping the entire canal system of New Orleans was just one step the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The new hurricane system also included a two-mile-wide, 26-foot-high barrier and pump stations to help stop water surges and redirect water as needed.

Flight is kind of a big deal these days—and the wood-frame Wright Flyer was key in making it happen. After a 12-second flight in 1903 in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilbur Wright continued to build upon their creation until engineering know-how pushed them to longer—and higher—places.

The adjectives to describe Frank Gehry's 2003 concert hall in Los Angeles flow as freely as the form of the structure. Known for using a mix of materials, the Walt Disney Concert Hall features a stainless steel skin, which was chosen for its ability to curve as much as its cost savings. Inside, the hall takes on a completely different appearance with Douglas fir and oak, which helps with its acoustics. There's a dichotomy of Gehry embracing shape throughout the design for both acoustics and aesthetics.

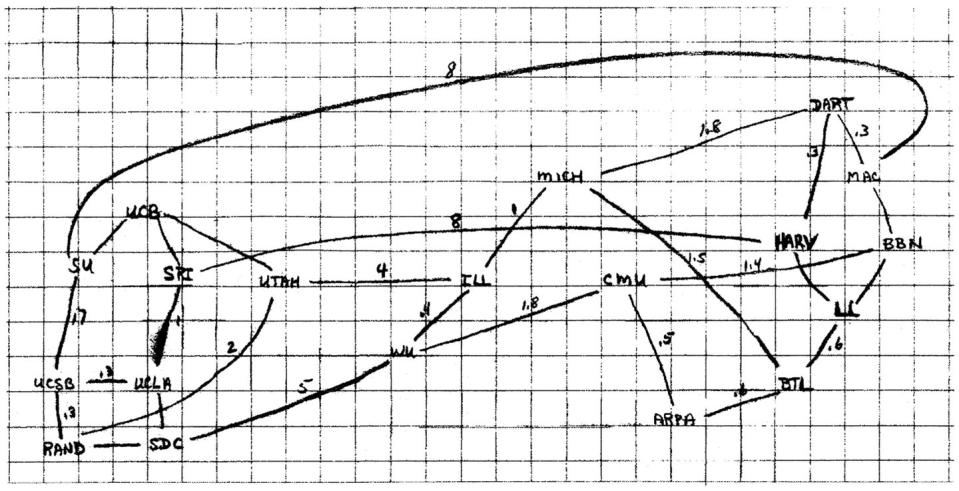

When the U.S. Department of Defense started linking computers together across research institutions in the 1960s, leading to the ARPANET effort testing file transfers, it laid the foundation for an entirely new way of computer-based communication. This technical engineering know-how helped usher in the internet and change not just one country, but the entire global communications protocol.

The seven-year project to dig out the Holland Tunnel, connecting New Jersey to New York, opened in 1927. Not only was excavation under the Hudson River water a feat in itself in the 1920s, but the project's chief engineer, Ole Singstad, created the first mechanical ventilation system used in a tunnel, helping dissipate the potentially toxic buildup of gases from vehicles using the tunnel.

The 1793 invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney showed ingenuity in early American establishments, even if there were unintended consequences for the progress. The hand-cranked gin separated seeds at a rate of 50 pounds of cotton per day, an improvement over 50 times of doing the work by hand. This sped up the amount of cotton sent to textile mills, but also pushed plantations larger, increasing the slave trade.

Stadium technology across the country has continued to evolve, but one of the most innovative was the 2017 opening of Mercedes-Benz Stadium. It has a signature retractable roof, featuring eight 220-foot-long “petals” that appear to open and close akin to a camera aperture, but run in unison along linear tracks. Inside, the first 360-degree halo videoboard rings the entire stadium, a 58-foot-tall, 63,000-square-foot continuous screen.

The consequences of this development weren’t unintended. The creation of the Manhattan Project took the collective know-how of engineers, physicists, and chemists to develop an atomic bomb by 1945, first tested in the New Mexico desert. The final result was the destruction of two Japanese cities, the ending of World War II, and the ushering in of the Cold War era.

Cleaning up the physical and environmental mess left by the Manhattan Project has proven tougher than its creation. The Hanford Nuclear Waste Site in Washington state was the home to nine nuclear reactors and five plutonium processing complexes needed to create the country's nuclear arsenal. The current cleanup project requires turning 53 million gallons of radioactive sludge-like waste in 177 underground tanks into vitrified glass for long-term safe storage, an engineering marvel at all levels.

40 of America's Most Impressive Feats of Engineering

When engineers figured out how to force the Chicago River to flow in a different direction, that's a feat. When they spanned the Pacific Ocean in San Francisco with the Golden Gate Bridge, that's a feat. Or even when engineers carved precise measurements into hillsides with rudimentary tools—whether for a road or a monument—that's a feat. Explore 40 of the most impressive engineering feats in American history.

From canals to bridges and rockets to roads, engineering in America has plenty to offer.

Solve the daily Crossword