Wild Life, Brilliant Talent: Genius Of Singer-Songwriter Judee Sill Honored In Documentary ‘Lost Angel’

Singer-songwriter Judee Sill packed a lot of living into her 35 years, much of it hard. Drugs, reform school, losing her father when she was just 8. Of her mother she said, “She was mean on top of being dumb.”

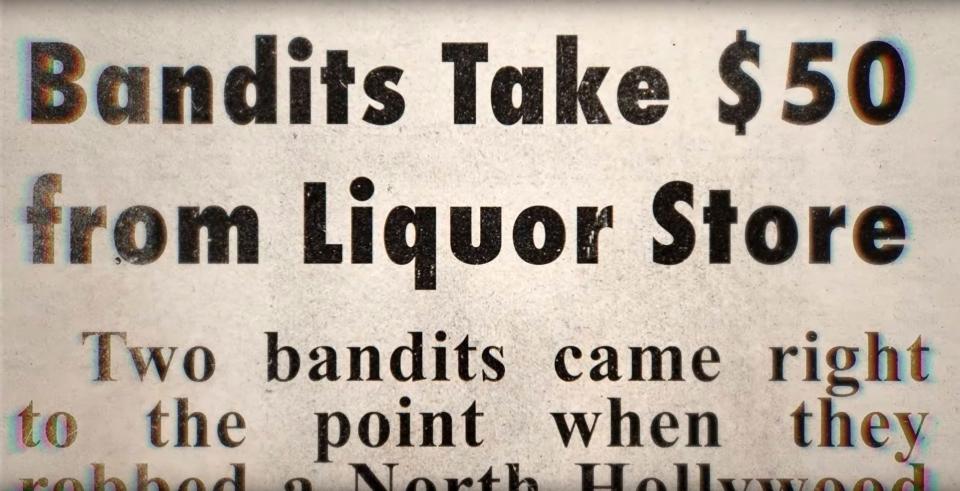

In her late teens, in the early 1960s, she got involved with a bad hombre in Southern California and they pulled off a few armed robberies. In one incident, she reportedly told a guy behind a liquor store counter, “Okay, mother sticker, this is a fuck up!” Humor she did not lack.

More from Deadline

As a child Sill learned piano at an upright in a saloon owned by her dad. She mastered other instruments, including bass and guitar. In juvenile hall – where she was sent after an arrest for forging checks – she played the organ. Somehow, through cracks in the unpolished concrete of a difficult youth, a flowering talent emerged. She could draw, she could sing, and she could write remarkable songs that synthesized rock, classical, country, and gospel.

Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill, which just debuted on major VOD platforms, examines the life and troubled times of a performer who almost, but never quite, gained star status. The film from Greenwich Entertainment, directed by Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom, appeared in theaters last month.

“It took about 10 years to make,” Brown said at a recent Q&A in Los Angeles. He discovered Sill’s music long after her death in 1979 from a drug overdose. “When YouTube started, the Old Grey Whistle Test version of Judy performing ‘The Kiss’ appeared and it had a very strong effect on me,” he noted, “and I figured it would also have on Brian and I showed to him maybe a year afterwards, and it did.”

The documentary retraces Sill’s turbulent upbringing in Northern and Southern California and what might be called an improvised existence. She married at 19, getting into heroin with her husband (the marriage was later annulled). To support her drug habit, she did occasional sex work. For a while, she lived in a Cadillac with five other people, sleeping in shifts. Sill developed an avid thirst for fame, perhaps to compensate for a lack of attention from her mother and stepfather who spent their days fighting and drinking. The way up and out was through songwriting.

Her first hit was “Lady-O,” recorded by The Turtles in 1969. Jackson Browne and Graham Nash, who share their memories of Sill in the documentary, became aware of Judee’s outsized gift; Browne urged David Geffen, who was then launching Asylum Records, to check out Sill. The budding record mogul signed her as the first artist on his label. In short order, Sill was joined at Asylum by Browne, Linda Ronstadt, J.D. Souther, The Eagles, Joni Mitchell, and Tom Waits.

Sill’s song “Jesus Was a Crossmaker” was inspired in part by a romantic relationship with Souther (he also appears in the documentary). The lyrics “He’s a bandit and a heart breaker” might sound vengeful, but Sill turns it into a healing, almost ethereal experience that touches on pain but makes space for the divine.

Lost Angel features rare performances of Sill in concert, some captured on early Portapak equipment, a portable video recording system introduced in 1967. The directors also gained access to Sill’s notebooks containing journal entries, song lyrics, and drawings.

“We knew we wanted to somehow, some way, make a first-person film with Judee as our kind of tour guide through her life,” Lindstrom explained at the Q&A. “We didn’t know how we would achieve that. Four years into the project, we were very lucky to track down a journalist from from the L.A. Free Press named Chris Van Ness, who had done a great interview with Judee in 1972, and he had kept the audio tape. And at this point, Chris was living in Connecticut. He was wheelchair bound. He said, ‘I have the tape in the attic, but I physically can’t get to it.’”

Brown drove from New York to Connecticut to retrieve the recording. With Van Ness directing him where to look, Brown fished around in the attic of the journalist’s house.

“There it was, a cassette tape that said ‘Judee Sill interview 1972,’” Brown recalled. “We didn’t know if anything would be on it. We digitized it and there was Judee’s voice, and there she was telling her life story up until 1972.”

The filmmakers obtained other materials from Judee’s survivors. “All her worldly possessions were in a box at her cousin’s house and her journals were in there and her drawings,” Brown said. “The drawings in the journals became the basis of the [film’s] animation style.”

Joni Mitchell, the blond-haired beauty from Canada with the jazz-inflected phrasing, may have been easier to market to a music audience than her contemporary, Sill. Judee, with a voice of Mitchell’s range – though with more twang in it – performed in rimless spectacles, unaffected, seemingly oblivious to the imperatives of “image.” Attempts to gussy her up, like a photo shoot in which Sill was made to look like a winsome bride, fell flat.

“There’s photos in [the film] of her in a wedding dress that Henry Diltz, the great photographer, took and she looks very uncomfortable in those photos,” Brown observed. “She didn’t want to be made up to look that way. So, there was a certain degree of not playing that game.”

Her music wasn’t easily categorized — the sound or the themes. She wrote in terms that could be celestial, of ecstatic modes of spirituality and sensual urges. In “Crayon Angels,” she wrote “I sit here waitin’ for God and a train/To the astral plane.” “The Lamb Ran Away From the Crown” contains these lines:

“Though the beast within me’s a liar

He made me glow with a strange desire

And I rode on the fire

With a blue sacred opal to bless the battleground.”

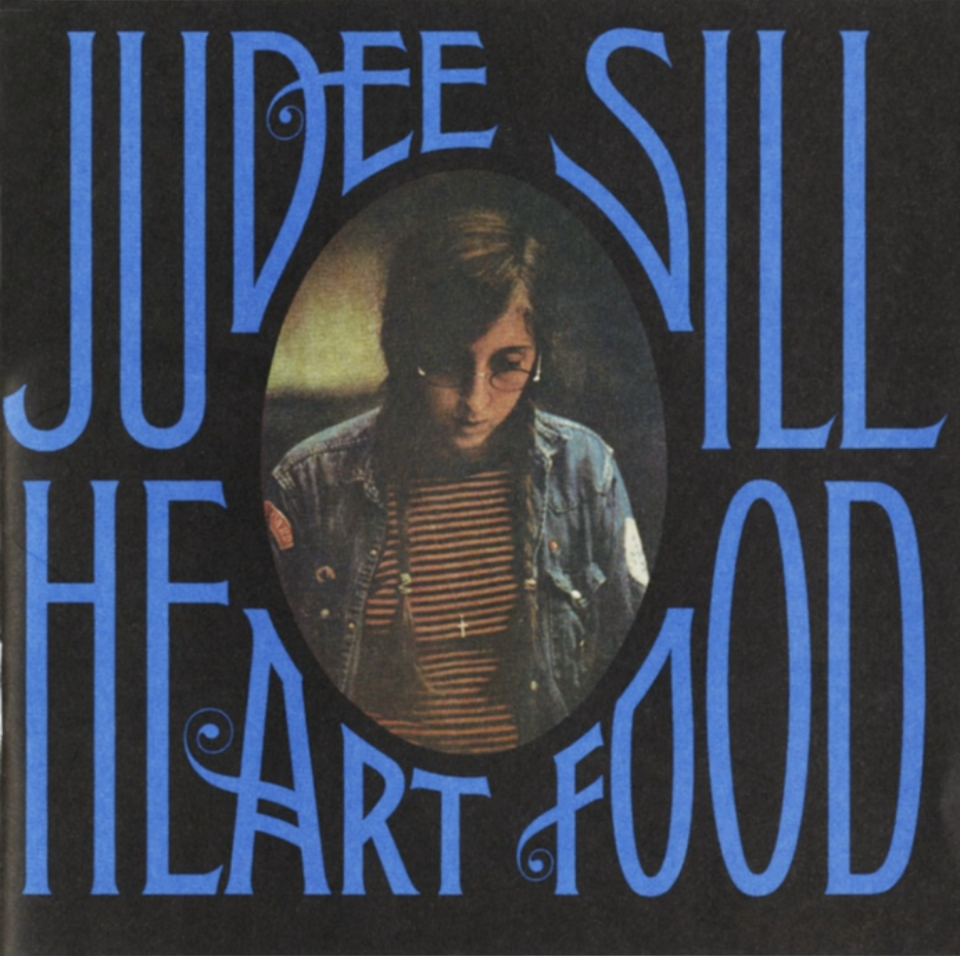

Success on a huge scale never came her way. Asylum Records dropped her after Sill’s second album, Heart Food, failed to take off, though it produced songs that are loved today, including “There’s a Rugged Road,” “The Pearl,” and “The Kiss.”

“One thing that this experience has given me is just the need to question what does it mean to ‘make it’” Lindstrom commented. “How can you possibly listen to ‘The Kiss’ and think that Judee did anything other than make it, a hundred times over? And maybe those exact things that prevented her from reaching that superstar level 40 years ago is what is causing her to be rediscovered now by a whole new generation. And she’s bigger than she’s ever been.”

By the time Sill died in 1979, she had been forgotten. The New York Times didn’t note her passing, nor did other major publications, although the Times made up for it with a belated obituary in 2020 as part of its “Overlooked No More” series. Those who knew and loved her – friends, family, and collaborators Browne, Nash, Souther, and Tommy Peltier — never let go of her memory.

“Everyone talked about just what a light she was and how much fun she was,” Lindstrom said. “They really wanted to make sure that we told her full story and that she had been reduced to this one-note Wikipedia ‘tragic artist’ thing. And it was like, no, that’s not who Judee was. And so we really wanted to show her fullness.”

Best of Deadline

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2024: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

2024 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

2024-25 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For Oscars, Tonys, Guilds, BAFTAs, Spirits & More

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.