TV's Antihero Era Is Over. Welcome to the Golden Age of Hope.

In the final scene of Station Eleven, HBO’s excellent new post-apocalyptic miniseries, two main characters stand before a massive forked path in the forest. After a 20 year journey together, they turn to one another, embrace in a hug, and head in different directions. It reads like a cliché, here in plain typeface, but it doesn’t feel like one while watching. And contrary to the image, the move is more about a convergence than dichotomy. That’s because Station Eleven—like many other current storylines—isn’t dabbling in predictable, conflict-free conclusions or nihilistic plot-lines. Instead, knotty sincerity is on the rise, and TV is better than it's been in years as a result.

For decades, antihero narratives have dominated in prestige television, but recently, we have entered a period of noticeable, compelling reinvention. Creators are opting out of the egocentric central figure for nuanced earnestness. (And I’m not talking “earnest” in the way that This Is Us terrorizes tear ducts on a weekly basis, but rather vignettes and characters that honor the complexity of life.) Like any seemingly overnight pivot, this shift has been inching along in this direction for a while.

Culture—TV, movies, music, literature—always responds to its surrounding circumstances. There are the obvious changes, like recent Covid storylines incorporated into pandemic-produced television seasons, or, as happened twenty-one years ago, quick edits to film and TV following the 9/11 attacks to re-draw the Manhattan skyline. But there are also the gradual changes: biting satire, inspired in part by a fraught political landscape and a never-ending war in the Middle East in the 2000s, replaced the laugh out loud, punch-line comedy that defined the 80s and 90s. The climate, rife with cynicism, fears of recession, and unease in D.C., was the perfect incubus for the antihero era. And not long after the turn of the century, infallible and authoritative protagonists from the decades prior were kicked out, replaced by protagonists that suddenly looked an awful lot like villains.

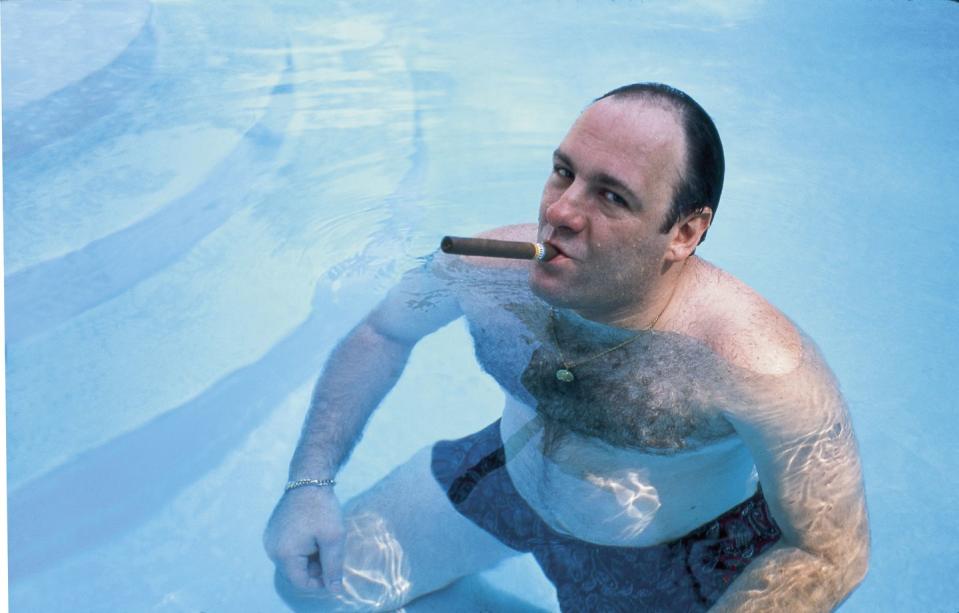

The chapter was pioneered by the likes of The Sopranos and Sex and the City, both of which debuted not long before the 90s drew to a close and for the 20 years that followed, we were inundated with self-serving figures who blurred the line between moral righteousness and personal gain. The ambiguity of Tony Soprano and Carrie Bradshaw—whether or not you found them palatable, much less wanted them to succeed—made television debate fun. It also ushered in a host of other questionable figures like The Wire’s Omar Little, Mad Men’s Don Draper, Breaking Bad’s Walter White, and Dexter’s Dexter Morgan. Ten years later, Veep’s Selina Meyer, The Americans’ the Jennings couple, and Eastbound and Down’s Kenny Powers would join the lot.

Whether you loved them, hated them, or loved to hate them, they were fun to watch. And in turn, those characters and their creators created some of the most memorable, though gruesome, TV moments of the 2000s. On House of Cards, Frank Underwood pushed a woman in front of a train. Game of Thrones' resident baddie, Cersei Lannister, blew up an entire church full of people. Jax Teller, on Sons of Anarchy, literally shot his mother in the back of the head. Those scenes defined the pop culture landscape and, to some extent, we rooted for them all.

But as the hope that defined the Obama years began to fade and we were suddenly left with the painfully unlikable matchup of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, everything else seemed to go to shit, too. Mudslinging every night on cable news. Unprecedented access to information. Grim political prospects—which resulted in the worst possible outcome—and eventually, a social justice reckoning in response to decades of truly fucked up behavior. A pandemic and woefully inept leadership. Increasingly, diving into the universes of these murky characters felt like a slog each night. When women, dressed as handmaids inspired by the initial season of The Handmaid’s Tale, showed up to protest a Supreme Court nominee, that was, for me, when I knew the scales had tipped too far away from entertainment and into the direction of dread.

And so TV has found itself at its own metaphorical fork in the road. But so far, it hasn’t pivoted back to infallible heroes—characters like Thomas Magnum or Jessica Fletcher, which ruled airwaves in 1980s. The main characters we’ve begun to see are still flawed. They’re also still sometimes selfish. But they also have the capacity and desire to evolve. Some of the earliest examples come around the time of the 2016 election. 2014’s The Leftovers explored the existential crisis that arises when two percent of the world’s population disappears, leaving the remaining 98 percent wondering where and who to become next. Mike Schur’s The Good Place positioned four hell-bound strangers together in a seeming utopia with the expectation they’d torture each other for eternity. (They didn’t.) Dan and Eugene Levy created Schitt’s Creek, focused on the insufferably wealthy Rose family whose financial demise lands them in a podunk motel. All three series went on to be critical and commercial darlings, amassing more fans as each revealed its end game, as all three chronicled the betterment of their characters. Each considered that, perhaps, there’s something to learn from the disaster.

That trend towards realness and hard won lessons has continued. Storytellers are allowing their characters to learn to operate outside of their own interests, rise to the occasion, and gain perspective. And what’s so beautiful about it is, much like life, their progress as humans neither saves the world or causes widespread despair. For much of the first season of Ted Lasso, critics complained that Sudeikis’s title character was too optimistic for our world, to the point of being unbelievable. Others went so far as to liken his cheery disposition to its own case of disguised toxic masculinity. The truth is that he’s damaged goods, thinly shrouded in dad jokes and good vibes until he can go home, alone, and mull in his own depression. It’s not until Season Two that we see him begin to address that darkness.

For other series, like Squid Game or WandaVision or Mare of Easttown, that evolution unfolds more quickly. The first, Netflix’s runaway Korean-language hit of 2021, places its characters in the most dire of circumstances, where the only thing keeping them alive is their own selfish interests. But as the series moves through its short run of nine episodes, it grapples with the idea that even in an oppressive system that relies on 455 people to die for one to win, people can still choose honor and goodness, even if it costs them their lives. WandaVision helped revive the stakes in the superhero universe. After a decade of big booms, few deaths, and even fewer consequences, the series allowed viewers to see a character on their truest, granular level. The most vulnerable thing about a superhero is their humanity, and Disney+’s first Marvel outing allowed us to follow Wanda Maximoff through the correcting of her own missteps, made in the throes of grief. It grounded the episodes in an almost bizarrely personal way. Mare, billed as a series about a grisly murder, was actually a rumination on one woman’s rocky, one-step-forward, two-steps-back path to forgiving herself.

Perhaps the most undeniable representation of this evolution came when Dexter: New Blood, the well-received Dexter reboot that debuted last year, literally killed off one of the antiheroes that most defined the 2000s. Speaking about his character finishing off his sociopathic father, series star Jack Alcott told Esquire, “Harrison definitely has a version of the Dark Passenger [Dexter’s term for his murderous impulses]. But if Dexter's in the passenger seat/driving, then Harrison is in the third row and he can see it in the rearview mirror.” Even Danny McBride got the message, abandoning his asshole schtick on Eastbound & Down and Vice Principals for something better. In this next generation of TV characters, even the deranged have a touch of empathy. (Save for the actual sociopaths, like the Roys on Succession, who are so post-antihero and so completely irredeemable that the drama instead operates like a comedy; forcing the audience to literally laugh in the face of their behavior.)

That brings us back to Station Eleven, a show whose finale landed at the start of the year. By the time main characters, Kirsten and Jeevan, find themselves at that fork, their work has been completed. Together, the one-time strangers forged a life with one another until circumstance pulled them in different directions. What once might have served as a trope depicting the binary of good and evil was now simply a directional choice. (It’s not hard to imagine a show like Buffy the Vampire Slayer using this moment to bang its audience over the head with which path was right and which was a moral failing.) It was a reminder that there’s no correct way ahead, just hope, and that all we need do is continue to move forward.

Whether it's society that changes art or art that changes society, we’ll probably never know, but this new mode of storytelling certainly feels more aware of where we as a culture are at in 2022. The darkness of life still exists, but it’s being called by its name, and hope lines the edges. There will always be room for gore and reprehension on television (see: Showtime’s Yellowjackets). But nipping at its heels is the idea that we are ready for the earnestness that comes from a character’s introspection; that there really is more to learn about the journey than the destination.

You Might Also Like