The trailblazing story of Sparks: "What we’re doing is making music that we can’t hear anywhere else"

It’s still an unshakable image: Sparks on Top Of The Pops in the summer of 1974, performing This Town Ain’t Big Enough For The Both Of Us, their first hit. The contrast between the two Mael brothers is striking. In neat shirt and tie, with swept-back hair and Charlie Chaplin moustache, the immobile Ron glares out from behind his electric piano. Meanwhile, pretty-boy sibling Russell struts about in a dark suit and satin scarf, his head a tumble of falling curls.

John Lennon is among the 15 million viewers watching at home. Stupefied, he phones Ringo Starr – so the legend goes – and tells him he’s just seen Marc Bolan singing with Hitler.

Then there’s the track itself. Built around a jabbing keyboard riff fed through an echo unit, strafed with gunshots and hitched to a relentless rhythm, This Town is topped by Russell’s vaulting falsetto. Lyrically it’s a Dadaist torrent of bombardiers, beating hearts and zoo animals. In the year of power cuts and the three-day week, Sparks seem like weird exotica from another universe. Their peers on tonight’s show – Bryan Ferry and Bad Company included – are rendered one-dimensional by comparison.

This Town… peaked at No.2 in the UK. Sparks’ sudden popularity was quickly compounded by another Top 10 hit, Amateur Hour, and a parent album, Kimono My House, loaded with dazzling art-pop songs that challenged convention yet were also fabulously accessible. Sparks were sensational: sharp, clever, witty and new. Their subsequent UK tour provoked hysteria wherever they went, attracting hordes of screaming girls. Serious music fans adored them too. Melody Maker readers voted Sparks the brightest hope for ’75.

“We’d always idolised British bands,” Ron Mael explains today. “We always attempted to be like The Who or The Kinks, even though, stylistically, it didn’t turn out that way. So to actually be brought over to the UK by Island [Records] and live out that dream was something amazing.”

“Ron and I were huge Anglophiles, so to have it all happen for us was an incredible experience,” Russell affirms . “The hard thing to grasp was that our appeal was on so many different levels. Our image and the music was appealing to a lot of young people, but the lyrical side wasn’t consistent with themes for audiences full of screaming girls. So there were a lot of incongruities at the same time. But I think that’s also what made it a pretty special thing.”

Since that first flush of Sparksmania, the Maels have hardly stopped. They’ve made a habit of flipping the prescribed notions of pop music. Not only by proving that brothers in bands can co-exist in lasting harmony, but also that the passage of time needn’t dilute the creative juices. Sparks have freely changed courses and styles over the years – encompassing everything from hard rock to electronica, dance music to neo-classical pop – but the sheer quality of their output has rarely dipped.

They remain daring provocateurs in an increasingly risk-averse world. The latest proof is The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte, their twenty-sixth studio album. It’s everything that makes Sparks so remarkable: bold, transgressive, in-your-face adventurous. A meta-modern pop opera.

“I think we both feel that what we’re doing is making music that we can’t hear anywhere else,” posits Ron. “And we’re fortunate that most of our followers expect to be challenged. They’d feel disappointed if we weren’t doing things that were pushing it.”

“Getting complacent in this period of our career would be the saddest thing for us,” Russell adds. “We always fight desperately hard to move on and try new things, to be as bold as we can. That’s always been the unspoken credo ofthis band.”

This isn’t just fighting talk. Deep into their sixth decade as recording artists, Sparks sit on the threshold of one of the most exciting phases of their lives. As we soon discover, it’s a remarkable upturn in fortunes. One that sees rock’s greatest and most enduring cult duo finally achieve what they’ve always wanted.

It’s early morning in Los Angeles when Classic Rock catches up with the Mael brothers via Zoom. Seventy four-year-old Russell, with a dark mop of hair matching his casual shirt, sits against a white backdrop dominated by a tasteful fireplace, on which sit a number of ornaments and odd figurines. On the wall is a vintage poster for Kimono My House.

Across town, Ron (three years his senior) looks debonair in a navy blue jacket, his pencil-thin moustache and round glasses providing some trademark symmetry. There’s a full bookcase behind him, topped with clear plastic cases containing some pricey-looking running shoes. The elder Mael is an inveterate collector. He began accruing Nike Air Jordans in the early 80s. More recent obsessions include snow globes and hand sanitisers (neither of which, sadly, are on display today).

Both men exude an easy, urbane charm. They’re bright and articulate, bouncing between topics and leaving space for the other in a way that you imagine mirrors their working practice in the studio. They’re rightfully enthused about The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte, an album alive with enough inventive energy to put bands a third of their age to shame.

Among its many moments that dazzle are Nothing Is As Good As They Say It Is and We Go Dancing, both of which carry the mordant echo of classic early-70s Sparks. It’s fitting, then, that The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte sees them back on Island Records, with whom they first signed half a century ago.

“Island heard the album and really responded positively to it,” Russell explains. “And we were really happy that the reason they wanted Sparks was not based on our past, necessarily, but the music we were making now, as something really significant and modern. It’s kind of an amazing story. I think they see the album as fresh in the same way that Kimono My House was in 1974."

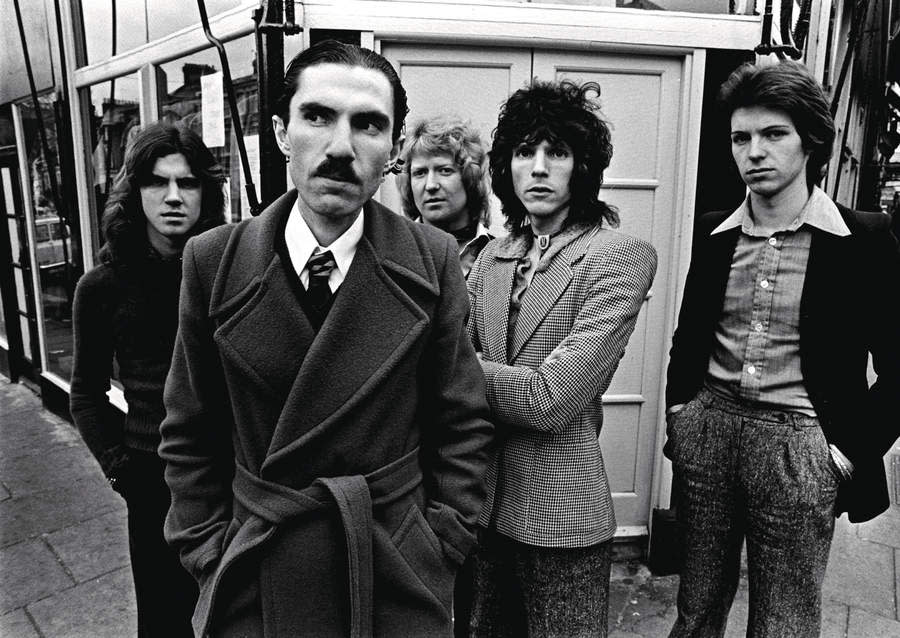

Back then, Sparks had been rescued from relative obscurity. The band, led by the Mael brothers, had released two low-selling albums on the Bearsville label (the first one produced by Todd Rundgren) in the US. But Island saw their potential and threw them a lifeline. Relocating to London, the Maels put together a new five-piece line-up and set about recording Kimono My House in the winter of ’73.

“Island had this philosophy of being inclusive of a sound that had a strong sense of originality,” recalls Russell. “It didn’t matter whether it was a reggae group from Jamaica or a stylised rock band like Free, it could all be valid as long as it had a special stamp.

“Ron and I initially wanted Roy Wood to produce Kimono My House. We both loved The Move because they typified great British music – amazing melodies and great singing. But it turned out, for whatever reason, that Roy chose not to produce it. That’s when Muff Winwood stepped in. He’d been bass player in the Spencer Davis Group, which was another plus – and I was thinking that maybe he’d bring his brother [Stevie] in to help me with my vocals!”

Acrobatic music and vocals aside, Sparks also dealt in gleefully subversive lyrics, from tragicomic suicide pacts to Albert Einstein and thwarted equatorial rendezvous.

“Having humour in pop music is sometimes considered kind of frivolous,” says chief lyricist Ron. “But we always felt, because of the bands that we originally loved, that lyrics could operate on two levels. A song can be humorous and still work on another, deeper emotional level. Even to this day I marvel at those early Who songs. Sometimes I feel it’s a shame that Pete Townshend has grown up emotionally, because we haven’t.”

The Maels also kicked against the idea of formula. After Kimono My House and follow-up Propaganda came 1975’s Indiscreet. A theatrical marvel overseen by Tony Visconti, it playfully shifted shape between glam, swing jazz, orchestral pop and old-time vaudeville.

They followed up in typically perverse fashion – by ditching the band, returning to the States and making Sparks’ equivalent of a hard rock album. Bowie’s old guitarist Mick Ronson was going to produce what became 1976’s Big Beat.

“We rehearsed with him for a week or two, and we even have a rough rehearsal cassette with him playing those Big Beat songs,” Russell says. “He really liked what we were doing, and his playing sounds absolutely amazing. But then he got an offer to join the Rolling Thunder tour with Dylan and left our project to do that. It’s a pity it didn’t work out.”

Big Beat sold poorly. It marked both the end of an era and Sparks’ tenure on Island. For better or worse, it also crystallised the outlier philosophy that would continue to guide the Maels for the rest of their career. There would be no pandering to expectations or past glories. Instead it was all about pure artistic instinct, creating music outside of conventional channels. Beholden to no one but themselves. As Ron puts it: “The best pop music makes you think, ‘What is that?’”

Giorgio Moroder appeared on Sparks’ radar around 1977. The Italian songwriter/producer was the man behind Donna Summer’s UK No.1 of that year, I Feel Love, a sequencer-driven classic that moved electronic dance music into the mainstream. Suitably inspired by the disparity between vocal warmth and cold machinery, the Maels hired him to collaborate.

The resulting 1979 album No.1 In Heaven, layered with modular synths and sequencers, repositioned Sparks as electro-pop mavens. It also delivered a couple of major hits in Beat The Block and The Number One Song In Heaven.

“Giorgio was just such a master at being able to incorporate electronic elements into popular music,” says Ron. “And in terms of songwriting, just to have our kind of focus affirmed by somebody like him was really something. To be exposed to that whole thing was really eyeopening for us. He was pretty merciless at going through our songs, but ninety per cent of the time he was right. Things have obviously changed enormously, because when we recorded No.1 In Heaven it was in a room with a bank of huge synthesisers along the walls. Now it’s all possible with a computer.”

In many ways, Sparks pre-dated the 80s synth-pop boom. The sullen keyboard player and the vivacious lead singer was a template adopted by any number of ensuing acts – Soft Cell, Yazoo, Eurythmics, Erasure, Pet Shop Boys. But rather than milking it for all its worth, Sparks explored their own left-field version of new wave on Terminal Jive before forming a new iteration of the band for the rockier Whomp That Sucker and the avant-pop stylings of 1982’s Angst In My Pants.

If Sparks’ mission was to polarise opinion, it worked. Angst In My Pants addressed notions of masculinity, libido and self-image, right down to the album cover shot of a just-married Russell and Ron (the latter in a wedding dress and clutching abouquet). And just when it seemed like Sparks had finally cracked their homeland with 1983’s In Outer Space (featuring their biggest hit to date, Cool Places), the Maels chose to follow it up with the resolutely uncommercial Pulling Rabbits Out Of A Hat.

It was almost as if they were hellbent on self-sabotage. When the record company moaned about the lack of dance-friendly songs and refused to fund a video, Ron and Russell mugged away on breakfast TV with a cardboard TV screen and set about making one themselves. As a final act of petulance, they named their next album Music That You Can Dance To.

“Most people follow the way that things should be,” Ron says, “but we always have been a bit more rebellious by nature.”

“Throughout Sparks’ whole career we’ve had blinders on in a certain way, where we like to ignore what’s going on,” Russell elaborates. “I think that’s what makes our music more pure and consistently in that Sparks world, where we don’t want to tone things down. We want to be even more eccentric in that way. And that’s something we’re proud of never having abandoned.”

This attitude has sustained Sparks through lean periods too. Come the late 80s, no one was buying their records. But despite being without a label, the brothers continued writing tirelessly, turning their attention to a film musical of Japanese manga series Mai, The Psychic Girl, in tandem with director Tim Burton. The latter abandoned the project in the early 90s, leaving the Maels utterly bereft.

Bruised but not broken, they eventually recovered with 1994’s punningly titled Gratuitous Sax & Senseless Violins. The album highlight was When Do I Get To Sing My Way, a satirical techno anthem that alluded to Sparks’ invisibility over the past six or seven years. ‘When do I get to feel like Sinatra felt?’ Russell sings in mock insolence. The need to be noticed, however, was all too real. The single proved to be a hit across Europe. In the UK it was Sparks’ biggest success since Beat The Clock a decade and a half earlier.

Their resurgence was crowned by 2002’s Lil’ Beethoven. An audacious reinvention of the Sparks sound, forgoing beats for thrusting string arrangements and vast multi-tracked vocals, it was their finest album since Kimono My House. Sales took time, but critics, in both the UK the US, hailed it as a masterpiece. The Maels were truly back, and more vital than ever. Among the various people who got back in touch was an old ally, Island Records founder Chris Blackwell.

“He’d heard Lil’ Beethoven and just loved it,” Russell recalls. “And we ended up rekindling our relationship. It wasn’t a nostalgia thing, either. He really loved The Rhythm Thief, in particular. He said it was the kind of song that should’ve been a hit. When he first heard it in his car, he pulled over to the side of the road to listen: ‘My God, what is that?’”

You know you’re culturally important when the documentary makers start calling. Sparks have turned down various offers to tell their story over the years, but British filmmaker Edgar Wright was a different proposition. He wanted to lay out the full scale of the Maels’ journey, from their youth in the Pacific Palisades of Los Angeles – where during the 60s they became fascinated with music, sport and Hollywood cinema – to the late-career renaissance of today.

The Sparks Brothers (2021) was a heartwarming portrait of the peaks and plains, triumphs and failures, of two of rock’s good guys. An admiring army of talking heads were at hand too, their sheer diversity giving an indication of Sparks’ extraordinary influence: New Order, Steve Jones, Beck, Sonic Youth, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bj?rk. Plus ex-bandmates, producers and collaborators, and a plethora of famous fans from the worlds of literature, TV and film. For a band often perceived as arch and a little distant, the documentary was an unusually moving experience.

“It made us see ourselves differently,” says Russell. “I think Edgar did an amazing job of presenting this emotional side to the whole Sparks saga that we maybe didn’t see coming. He told the history of the band in a way that treated every period equally. So there isn’t one golden era, it’s all part of a long process that Ron and I have been through. And this theme emerged of just being true to your own creative impulses, wherever that leads. A lot of people have really responded to that.”

“We also realised that so many creative people from different fields – writers, film people, musicians – had been following what we were doing,” Ron adds. “It was really inspiring to know that. We thought: ‘God, we’re actually pretty cool!’”

The release of The Sparks Brothers documentary crowned a recent run of critical and commercial fortune that saw the Mael brothers enjoy a run ofthree consecutive Top 20 albums for the first time since the mid-70s. It also coincided with Sparks’ first film soundtrack, in the shape of Annette, a romantic musical starring Marion Cotillard and Adam Driver. For Russell and Ron – film buffs all their lives – it was the realisation of a long-held ambition.

Now, on top of The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte, Sparks are writing and producing their own film musical, financed by the same company, Focus Features, that made the documentary. X-Crucior is still very much under wraps, but the brothers promise “a high-concept piece that could only really come from Sparks world. Something really unique to the whole genre of movie musicals”.

There’s also this summer’s ongoing tour of Europe, America and Japan, which included two sold-out shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall and the biggest headlining show of their career, at the Hollywood Bowl, next month. Remarkably, Sparks are more active, more multi-faceted and more popular than ever. Proof that perseverance and artistic temerity are their own rewards.

“I hate to speak of legacies at this point in our lives, but we want to be relevant in a current way without besmirching what we’ve done in the past,” offers Ron. “We’re aware of keeping the quality high, but what’s really inspiring to us is that we’re reaching more young people now. So it just feels like a really good period for us, where we can be creative in fields beyond doing Sparks albums.”

Russell agrees. “I think we’re getting to have the best of both worlds,” he says, smiling. “We’ll never not want to make pop music, but we’ve loved movies throughout our whole life. In a certain sense, writing songs has been a budget way to do little films, something visual and cinematic, without needing a fifty-million-dollar budget. But now, after all this time, we’re lucky enough to have both things going on simultaneously. It’s really a unique situation, and so satisfying in a huge way, for a band at this stage of our career.”

The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte is out now on Island Records. Sparks’ US tour kicks off on June 27 at the Beacon Theatre in New York. Tickets are on sale now.