"Towards the end it was not pretty. I scraped myself off the walls of insanity. I was barking like a dog": the last days of Deep Purple

In the late summer of 1975, 20-year-old Sounds writer Geoff Barton journeyed to the US to write an on-the-road piece about Deep Purple. Little did he know what he was getting himself into, as internal bickering, jealousy and addiction began to tear the band apart. In 2003, he revisited the trip for Classic Rock.

“I must say that the las tour for me was horrendously wrong,” Glenn Hughes says today of Deep Purple’s infamously doomed Mk IV line-up world tour. “Regardless of whether Tommy was a good choice as a replacement for Ritchie, there was a total line drawn around Deep Purple.

"It was me and Tommy, it was Coverdale sort of in the middle, and it was Lordy and Paicey on the other side – the two guys who were definitely not happy with our behaviour. I don’t know, man. Something happened when Tommy joined the band.”

Tommy Bolin had been playing guitar with Deep Purple for maybe four months when I noticed the first cracks in his relationship with the rest of band beginning to appear.

It’s early afternoon on a fine Indian summer’s day in September 1975. A 20-year-old cub reporter from British music weekly Sounds – that’s me – is standing in the foyer of London’s Swiss Cottage Holiday Inn, hanging on the house telephone, trying to call Bolin’s room.

Eventually, after several rings, a hoarse voice answers. Bolin apologises, says he’s only just woken up, and complains about a throbbing head – the result of an encounter with Newcastle Brown Ale the night before. Nevertheless, we arrange to meet in the lobby in just 15 minutes’ time.

Bolin arrives pretty much on schedule and, to his credit, looks only slightly bleary-eyed. He’s wearing a plain, pale-coloured T-shirt – there’s no ‘The Ultimate’ slogan emblazoned across it, that would come later – and dark blue, crushed-velvet trousers with the merest hint of a flare at the bottom. Tall-heeled snakeskin cowboy boots add a good couple of inches to his height, pushing him close to the six-foot mark. His trademark white peaked cap is perched at a jaunty angle on his head, and his long, blond-streaked, freshly showered hair frames a disarming baby face.

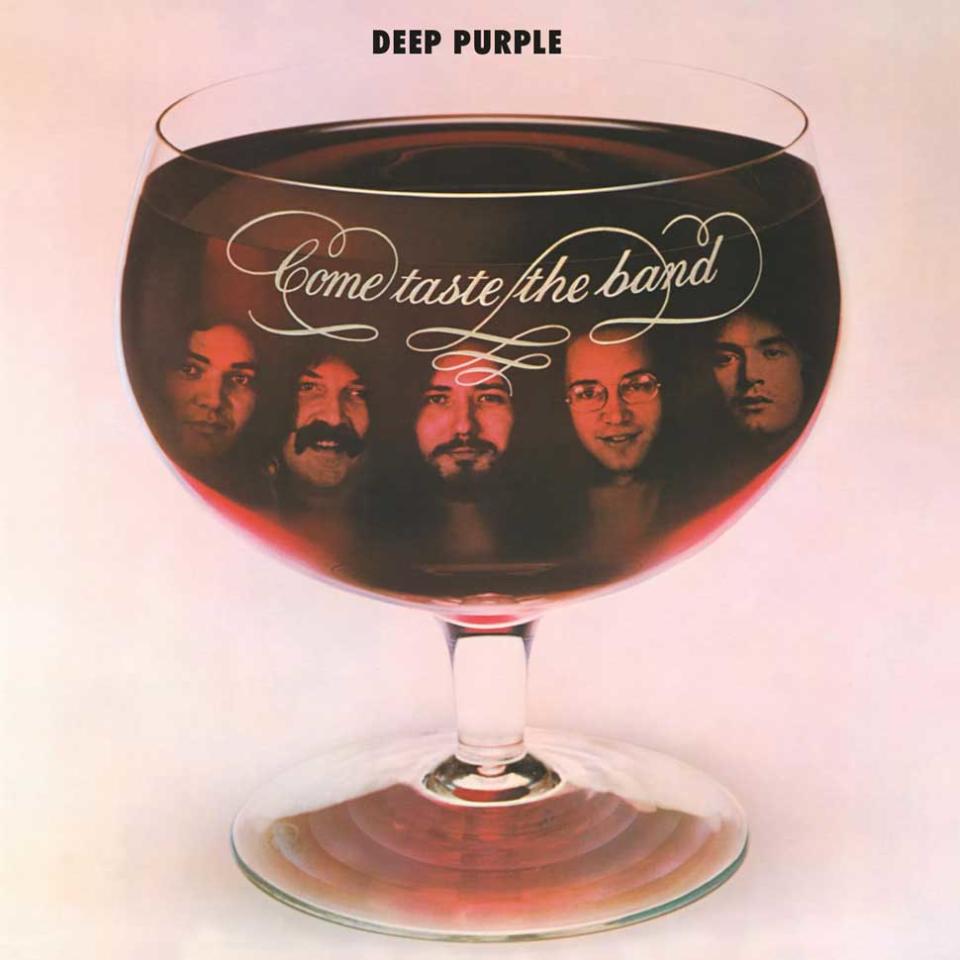

We decide to adjourn to the hotel bar, where Bolin immediately orders up a vast green salad. He devours it in seconds and comes up for air looking suitably refreshed (although to this day, I must admit I’ve never found a heap of crisp-leaf lettuce to be a particularly effective hangover cure). Next he gets a huge shandy with lots of ice and a swizzle stick with which to swirl the mixture around. Eventually, finally, we get down to business. Bolin has just finished recording the album Come Taste The Band with his recently acquired Deep Purple chums, marking the beginning of the Mark IV line- up of the band. Naturally I’m curious about how Bolin thinks the new record will be received.

Some commentators in the music press are already portraying him as a flamboyant Yankee interloper who has no right to be a member of an archetypal British heavy rock band. So how comfortable is Bolin in filling the dainty patent leather shoes of his predecessor, Ritchie Blackmore – to many fans the man who effectively was Deep Purple? And won’t people miss the taciturn Man In Black’s distinctive, Strat-slingin’ style of guitar playing?

Bolin remains unabashed. “I think they’re going to love it,” he predicts, that gravelly voice I heard on the telephone now replaced by slow, lazy, measured tones. “The new album is more sophisticated than the old Purple stuff, but I don’t think that’ll matter. The kids are more clued-in than they were a year ago, so I think it’ll be accepted. Highly. Very highly.”

Bolin pauses to take a sip of his super-cold shandy. “During Ritchie’s last days with the band,” he continues, “most of the members were so fucked off with everything. I think bringing in a new guitar player has made a hell of a difference. I honestly believe that we should keep some connections with the past, not sever them all, but at the same time begin to progress in our own direction.

“Everyone in Purple has brightened up,” he adds, stirring aggressively with the swizzle stick, the vortex causing lumps of ice to clatter loudly inside the glass.

Apart from receiving accolades for his fiery, fluid playing on Spectrum, a highbrow jazz-rock fusion album released by renowned drummer Billy Cobham, Bolin is pretty much an unknown in the UK at this point. He therefore takes a little time to bring me up to speed on his career to date. He was born on August 1, 1951, and christened Thomas Richard Bolin.

“What happened was, I developed a fixation for Elvis Presley at an early age,” he smiles, imitating The King’s famous surly curled-lip movement. Bolin says that seeing Elvis in concert when he was just five years old was a defining moment. With the strains of Jailhouse Rock ringing in his infant ears, he just knew he wanted to be a singer or some kind of musician when he got older. So he badgered his parents into buying him a guitar and, as he grew up, began to learn how to play the licks to Elvis songs such as All Shook Up.

“From there I started playing in Denny And The Triumphs and A Patch Of Blue – just a couple of little covers bands from the local neighbourhood. But the turning point probably came when I was kicked out of high school in my home town [Sioux City, Iowa] for having long hair.”

Bolin’s hippy parents didn’t push their son to return to school. His mother, Barbara, told the principal: “If you can’t accept him, he can’t accept you.” Despite being only about 16 at the time, Bolin quit the family home and travelled west to check out the burgeoning music scene in Denver, Colorado. He had a brief stint playing in a band called American Standard, then upped sticks again and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to take up the job of backing blues guitarist Lonnie Mack.

But before long Bolin returned to the state of Colorado – this time to the city of Boulder – and there he formed a band called Ethereal Zephyr with ex-American Standard keyboard player John Ferris, drummer Robbie Chamberlain and the husband and wife duo of bassist David Givens and singer Candy Givens, a Janis Joplin soundalike.

“We shortened our name to Zephyr and released an album on the ABC label [Zephyr, 1969] and one on Warner Brothers [Goin’ Back To Colorado, 1971],” Bolin reveals. “We were like this psychedelic blues band.” Zephyr enjoyed some success locally, and their first album scraped into the US Top 50. Their second record, however, was a flop.

(A quick aside here. While researching this story and delving into Zephyr’s past a little more deeply, I discovered that the band recorded a third album, without Bolin, before splitting. I also came across the first significant reference to drugs: a quote from David Givens has him admitting that Zephyr had something of a reputation in this department. He mentions that Bolin dabbled with THC (aka tetrahydrocannabinol), the main mind-altering ingredient in cannabis. Much later, in 1984, Candy Givens suffered a drug-related death – after a marathon drinking session, she gulped down a handful of Quaaludes, or downers, and drowned in the bath. But enough of that for the time being. Let’s return to the main feature.)

Bolin shrugs, as if Zephyr’s failure was no big deal. “So I left the band and started getting very much into the jazz-rock fusion scene – Weather Report, Miles Davis, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, all that kind of stuff. I formed a band called Energy and played alongside guys like Jeremy Steig, the flute player, and drummer Gil Evans.”

But Energy struggled to get a recording contract.

“We were playing really free-form, improvisational stuff. That was probably why we didn’t get signed; I think we frightened off a lot of record company executives. Anyhow, Jeremy persuaded me to set up base in New York for a while. And that’s where I met up with Billy Cobham. He’d just left the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and he invited me to play on his Spectrum album.”

When Spectrum was released, in 1973, people really began to sit up and take notice of Bolin. Because Spectrum is one of the definitive jazz-rock fusion albums. It certainly sounds just as miraculous, enthralling and bewildering today as it did back then. To call Bolin’s playing on tracks such as Stratus (later the basis of Massive Attack's Safe From Harm) and Quadrant 4 mind blowing is like saying the people whose heads exploded in the 1981 movie Scanners were simply suffering from tense, nervous headaches.

But what makes Bolin’s work on Spectrum truly outstanding is his symbiotic relationship with quicksilver keyboardist Jan Hammer, also ex-Mahavishnu Orchestra. Hammer’s synth snakes around Bolin’s guitar and squeezes it tight, coercing his six-string playing into uncharted realms of skittering fluidity. And with Cobham rattling around like an army of drum-playing Duracell bunnies linked to the national grid, the result is warp-speed, rapid-fire, high-energy, whirling-dervish eclecticism of the highest order.

What he did on Cobham’s Spectrum was a remarkable achievement for Bolin, aged just 21 at the time of recording (May 14-16, 1973). It’s all the more astonishing when you consider how the album inspired no less a guitarist than Jeff Beck to shun blues rock and record albums in a similar vein, such as Blow By Blow and Wired.

Next, with his reputation growing rapidly, Bolin was asked to succeed Domenic Troiano (who himself had replaced Joe Walsh) in the James Gang.“That lasted for about a year,” Bolin remembers. “I recorded the Bang album in 1973, and followed that up with a record called Miami a year later. But I left when Miami came out because I wasn’t happy with the way the band was going – we were like four individuals, not a unit, and it was hurting my playing.”

So Bolin “zoomed down to Los Angeles” to guest on some tracks on ex-Weather Report drummer Alphonse Mouzon’s Mind Transplant album – yet more of that frenzied jazz-rock fusion stuff. He then decided to stay in California for a while to try to get his own band together. Things didn’t go quite how he’d planned, but his next venture was to change his life dramatically.

“I had all the members except a vocalist when Purple called me up,” he explains. “I was very depressed at the time, and when I went along to play with Purple it was like a tonic. I didn’t know what to expect, but it was great. Purple are so tight, they’re a great outfit. I don’t think my playing has ever been better.”

I pause the brittle, nigh-on three-decades-old interview cassette tape for a moment of reflection. It’s easy to say now but – here on a rainy afternoon in July 2003, and with the obvious benefit of copious amounts of hindsight – I think Bolin may have been kidding me a little with those scratchy, age-old comments. Because, in truth, the guitarist’s association with Deep Purple was always deeply – and, ultimately, fatally – compromised.

In April 1975, just prior to joining Purple, Bolin signed a solo contract with Nemporer Records and got himself his own manager. Two months later, vocalist David Coverdale – inspired by the Spectrum album – was instrumental in getting Bolin to link up with him, bassist Glenn Hughes, keyboard player Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice to form the new-generation Deep Purple. But Bolin joined with the tacit understanding that he would also be allowed to follow his own, separate, guitar-playing career.

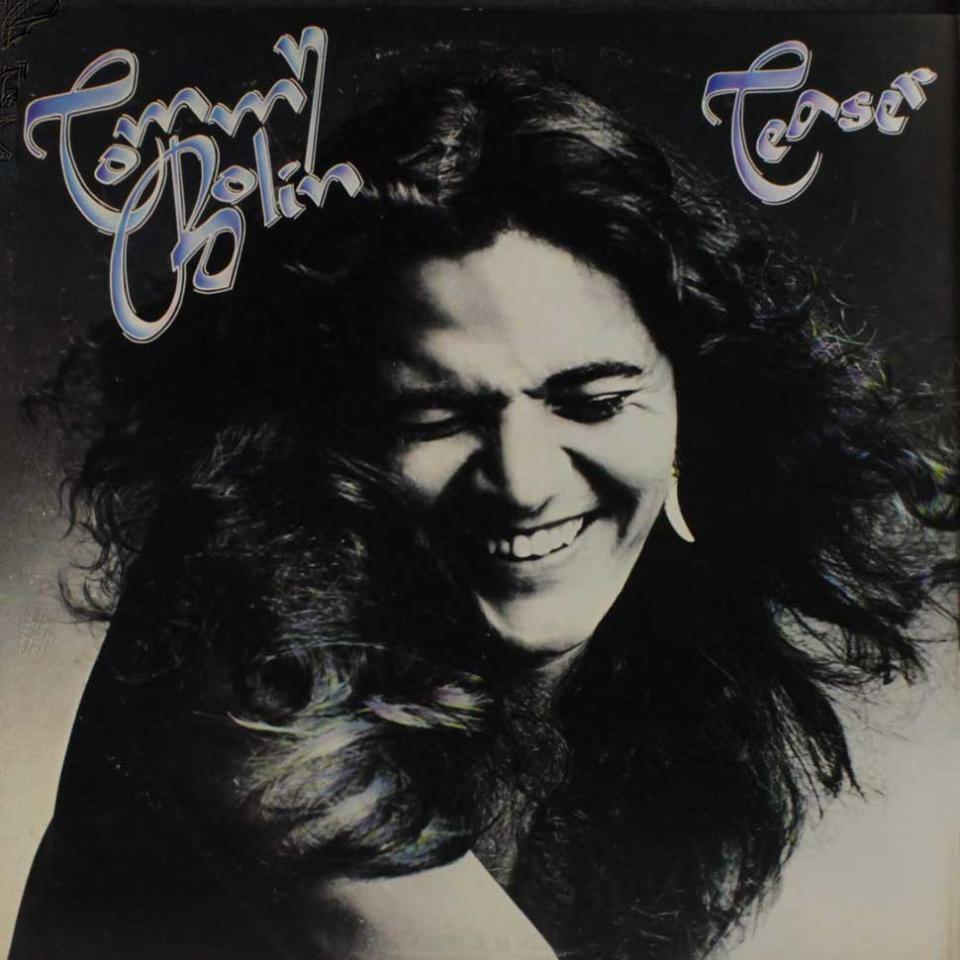

So, when Bolin flew to Munich in August 1975 to record the guitar parts for Purple’s Come Taste The Band, that album was just the mustard on the hotdog of his solo project, a record called Teaser. Bolin had begun recording Teaser the preceding June, but was forced to hold off mixing it until Come Taste The Band was completed. Teaser was eventually polished off the following October, and the two records – Purple’s and Bolin’s – arrived in the shops at more or less the same time. Which was an unfortunate scenario, to say the least.

The cover of Teaser came with a sticker proudly proclaiming that Bolin was ‘Guitarist of Deep Purple’. But, really, the whole dual-release ploy was a desperate hedging of the bets – like booking wife and mistress into adjoining hotel rooms. Or seating Arsenal and Spurs fans side-by-side at a derby game. Or inviting Les Dennis and Neil Morrissey to the same intimate dinner party. In short, it was a recipe for disaster. And so – along with another terminally toxic ingredient, called heroin – it proved.

Tracking back to that September 1975 interview for a moment, Bolin remains convinced that the schizophrenic Deep Purple member-cum-solo artist arrangement will work, while at the same time verifying the scheduling clash between Come Taste The Band and Teaser.

“I can blow my cookies off on my own albums, do what I want, be as selfish as I like,” he grins, taking a final gulp of his now rather lukewarm shandy. “I recorded most of Teaser in Los Angeles and parts of it in New York. I’m due to mix it here in London from October two to six, then I start rehearsals for Purple on the tenth for a world tour, so it’s worked out quite smoothly.”

But dig beneath the publicity speak and it’s evident that there’s a clash of interests going on.

“Here’s an admission for you,” Bolin declares as we shake hands at the interview’s conclusion. “I’m as excited about Purple’s album as I am about my own solo record. I honestly didn’t think I would be. I’ve been wanting to do my own album for so many years, and I thought nothing would be able to top it. But the Purple album has.”

Bolin pauses, and grins at me knowingly as he withdraws his hand. “Almost.”

Glenn Hughes today: “C’mon, you saw me at the start of my addiction. It was not pretty. Towards the end it was not pretty. I scraped myself off the walls of insanity. I was barking like a dog towards the end. There’s a quote for you: ‘Barking like a dog’.”

Meanwhile, what were Ritchie Blackmore’s thoughts on all this malarkey? By a strange twist of fate, I had interviewed Blackmore – also in London’s Swiss Cottage Holiday Inn, coincidentally – just a few weeks before my chinwag with Tommy Bolin.

Blackmore had been doing his first round of post-Deep Purple press interviews, promoting his new band Rainbow with singer Ronnie James Dio.

I remember Blackmore being in a typically grouchy mood when I met him in late July 75. But while he fumed about the noise being made by shrieking children in the nearby hotel swimming pool (“I hate little kids,” he moaned), I reminded him that he had once described Bolin as “one of the few American guitarists doing anything interesting”.

And it’s true. Blackmore appeared to harbour no ill feelings towards his successor in Deep Purple.

“Tommy Bolin is very good. He’s one of the best,” Blackmore told me between scowls, as the irksome kids queued up poolside to see who could make the biggest splash by dive-bombing into the water.

“I think Purple will probably be quite happy with him,” he continued. “He can handle a lot of stuff, including funk and jazz. Maybe they’ll turn into a rather different band, but I really don’t think so. I think they know that if they did they’d be just another funk band. They’ll still keep to the rock side of things, I’m sure of it. In fact the next album will probably be a lot rockier than my last record with them, Stormbringer.”

But one thing was plain: Blackmore was still upset about the funky direction Purple took on the Burn album, when Glenn Hughes and David Coverdale had been ushered in as replacements for Roger Glover and Ian Gillan. “I just don’t like that sort of music,” Blackmore snapped. “I hear it day and night in America and I’m sick of it all.

“I just didn’t like the way things were going with Purple,” he continued. “In the studio we’d be five egotistical maniacs, pushing up the faders so each of us would be progressively louder than any of the others. It wasn’t a team effort any more, and the songs seemed to have been forgotten. But at the same time it was all becoming too classy, too laid back and… cool. That’s not Deep Purple, Deep Purple are a brash, demanding band.”

Another thing: Blackmore said one of the reasons why he was looking forward to his future with Rainbow was “because we have a record deal where we make one album a year, and that’s all I want to do. I made sure that was in the contract.”

By sharp contrast – and I was amazed to hear this – Blackmore claimed Deep Purple back then had “a three-albums-a-year deal, plus tours of the world. Consequently, when I was with them, the music was suffering and we were just turning out any old stuff. There was a lot of padding involved, which I think is exploiting the public to some extent.”

Actually, I’m not sure if Deep Purple ever managed to achieve that annual three-album target, if indeed that’s the kind of deal they used to have. Blackmore could have been winding me up with those remarks. But I suppose the band came close enough in 1974, when they released two all-new studio albums in the same year: Burn in February and Stormbringer in December.

As the kids continued to splash around in the pool, Blackmore adopted a look of resignation. “Unfortunately, when you first join a band it’s very rosy,” he groaned. “When a record company comes up to you and says: ‘All right, lads, three records a year’, everyone thinks, oh yeah, that’s fine. That is, until you realise what you’re up against.”

But chuck a Tommy Bolin solo album or two into the equation, and the situation rapidly becomes impossible.

Incidentally, talking about wind-ups, a few months after our chat it was curious to see Bolin named as a correspondent in Blackmore’s divorce suit against his wife, Babs. Jeff Beck, Keith Moon, Salvador Dali and 12 roadies were also named. Bolin was later dropped from the suit.

Glenn Hughes today: “Listen to Stormbringer, Come Taste The Band… They’re funky. I made Deep Purple a little funky; Blackmore played funky on Stormbringer, c’mon! Paicey, and Coverdale, and Lord, they loved it.”

I was just leaving the Sounds office to catch a plane to join Deep Purple on tour in Texas in February 1976, when one of my colleagues on the staff said: “Better make the most of it, Geoff. They are going to break up, you know.”

It proved to be a prophetic comment. And even though I might be jumping ahead of myself a little bit here, it’s probably worth outlining some bare facts before I go any further.

In winter 1975, with new boy Tommy Bolin on guitar, the fourth-generation Deep Purple kicked off their one and only world tour. After some low-key concerts in exotic locations such as Honolulu and Hawaii, the band visited Australia, Indonesia and Japan, and then took a breather over the Christmas and New Year period.

The US leg of the tour commenced in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on January 14, 1976 and finished in Denver, Colorado, on March 4. Five UK dates followed: Granby Hall, Leicester, March 11; Wembley Empire Pool, London, 12 and 13; Apollo Centre, Glasgow, 14; and Empire Theatre, Liverpool, 15 – which is where the whole shebang reached its nadir. But more about that later.

Returning to that farewell scene in the Sounds office for a moment, I had to admit grudgingly to my colleague that the early signs weren’t encouraging.

Deep Purple’s Come Taste The Band album had received unexceptional reviews, and the global trek to promote it had got off to a shaky start. Already there were rumblings of lacklustre on-stage performances and apathetic audience responses.

And there had also been some worrisome episodes in Indonesia: Patsy Collins, a member of the road crew and also Bolin’s bodyguard, had died in suspicious circumstances after falling six storeys down a lift shaft in Jakarta; at showtime, riot police with machine-guns and fierce dogs had attacked and injured 200 Purple fans… Even so, as Tommy Bolin would say after he left the band: “The first gigs were the best. Then they got progressively worse.”

But, naturally, I was more than willing to give Purple the benefit of the doubt. After all, I was about to visit America for the very first time in my young life, on an all-expenses-paid trip, to see one of my favourite bands. Surely things don’t get much better than that?

Glenn Hughes today: “I remember it very clearly. Geoff, you were catching the addictive side of the band back then. Me and Tommy were on a tremendous drug run at that point. You saw first-hand what was going down. I thought it was normal, man. We weren’t drinking bitter, we were drinking cocaine.”

I recall four things with absolute clarity about that tour of Texas in early 76: bursting into Glenn Hughes’s hotel room in San Antonio; the crutches at the gig in Abilene; the record store incidents in Dallas; and the concert in Houston, the final one I saw before returning to the UK.

First things first. As a naive rock journalist barely out of my teens, I thought nothing of the two guys to start off with; I reckoned they were just a pair of fiercely dedicated Deep Purple aficionados; two guys in over-large cowboy hats, with a terminal dose of blind loyalty, a flashy American sedan and an inexhaustible supply of, erm, gasoline.

What happened was, I would fly with the five Deep Purple members and their entourage on board a specially chartered, twin-propeller-driven plane from city to city, gig to gig, and these Texan twins would pursue our trail doggedly by road in their wallowing Oldsmobile. They would turn up without fail to meet us at the hotel, backstage, in a restaurant, wherever, whatever, and they seemed harmless enough. I never really got into a conversation with them, but we used to nod in recognition as we passed each other by.

But the penny finally dropped when Glenn Hughes invited me to join him in his San Antonio hotel suite – for a quick after-show snifter, he joked. And I really did think he meant a glass of brandy.

I recall shuffling down a thick-carpeted corridor on the top floor of a slick skyscraper hotel and finding the door to Hughes’s room slightly ajar. As I knocked, I simultaneously pushed the door open – and I admit I recoiled as I was confronted by a low-life scene straight out of Brian De Palma’s Scarface movie.

There was a mound of cocaine – or ‘marching powder’, as Tommy Bolin called it on Teaser – piled up on a glass-surfaced coffee table. Hughes requested quietly that I close the door. He then beckoned me over to join him and the two so-called fans – the road-travelling followers of the Purple plane – who were also present in the room.

Unwittingly, I took a few steps forward to study the scenario more closely. Hughes and his mates were kneeling down on a luxurious rug in front of this mini-Millennium Dome of white powdery stuff. With rolled-up 100-dollar bills in their hands, they were getting ready with burnished razor blades to chop out pallid little trails of startling indulgence.

Glenn Hughes today: “What I didn’t realise was that these guys were the Rolling Stones’ drug suppliers, they were Led Zeppelin’s drug suppliers, and they got their claws into Deep Purple via me – they were giving me drugs; I never bought anything. I was thinking, this ain’t no big deal, everyone’s doing this, right? I was just there hanging out with these geezers.”

The ‘Abilene crutch incident’ I mentioned most likely came as the result of an ill-fated skiing accident. Although Texas has this popular image of hot sun, big sky, desert, cacti and tumbleweed, the southern state’s sizzling temperatures take a significant plunge outside the summer months.

About the turn of the year, the snowy mountains of nearby New Mexico become a popular holiday destination for winter sports enthusiasts. Midway through a stuttering Deep Purple set in Abilene, there was an event that looked sadly ironic – to me, at least. Someone who’d obviously come a cropper on New Mexico’s icy slopes, and who was present in the audience, threw his crutches high up into the air. It was a gesture that was supposed to denote his appreciation of the band. But, as I wrote in Sounds at the time: “To me, the action epitomised the situation on stage – Purple floundering around and in some plight, having been dealt a serious injury with Blackmore’s departure.”

A few days earlier I had raised my doubts with a freshly bearded – and noticeably overweight – David Coverdale. He immediately went on the defensive, particularly when discussing the merits of the Come Taste The Band album.

“The last thing I heard, which was at the beginning of December, the record had sold 130,000 copies in Britain,” he countered. “I think at one stage it was number nine in the charts, which is cool. Christ, what do people want? Worldwide the album has sold well. I for one am not complaining.”

But despite his supportive words, and in the spirit of Tommy Bolin’s extra- curricular activities, Coverdale also said he was eager to do his own solo thing.

“I’m keen to find out what I can do in a studio on my own,” Coverdale insisted. “When I record my own album it’ll be without any members of the band, because if I used any of them it would be judged as a Purple recording, not my own.”

And I could tell Coverdale wasn’t overly enamoured with his role in Purple when he added: “I’m going to sing on this solo album, rather than scream my balls off. I’ve been fucking screaming for years now, you know.”

It’s fair to say that by this point Coverdale was becoming increasingly marginalised in Purple. At the shows I’d seen so far he appeared to be spending an inordinate amount of time off stage, allowing Glenn Hughes to take over lead vocals on indulgent – and somewhat bizarre – workouts such as Hoagy Carmichael’s Georgia On My Mind.

Glenn Hughes today: “Here’s why: when you’ve got a bass player who plays creatively, and he’s playing with a guitar player who allows him to walk across the stage and jam with him… It was ad-libs and the kind of free-form playing that only players can play. It wasn’t the Grateful Dead, but it was certainly 12 minutes of Gettin’ Tighter. In such a situation, what’s the lead singer going to do? He’s going to walk off stage; he’s not going to stand there playing maracas for half an hour.”

Coverdale agreed that he was playing a somewhat fragmented role in the band, but insisted: “I have no one to blame for that but myself.”

Stroking his wiry, newly grown bristles, he added: “I suggested the songs for the set without realising how limiting they were – for me, at least. They’re very monotone. We’re not doing Mistreated, and I miss that song. But, after all, I’m one fifth of a concept, and at the moment it’s very frustrating for me.”

It’s time I returned to my major recollections of Purple’s tour of Texas, and the third one on the list: what went on at those Dallas record stores. This was where the tension between Deep Purple and Tommy Bolin became palpable.

In Dallas I accompanied Bolin and Hughes on a round of personal appearances that included visits to a couple of record shops. One was a vast, Tower Records-style place; the other was a more intimate specialist hard rock emporium. In both stores, however, the displays for Bolin’s Teaser album far outweighed those for Purple’s Come Taste The Band. All credit to the marketing department at Bolin’s label, it was beating Purple’s hands down. But record company shenanigans were the furthest thing from Hughes’s mind, that afternoon in JR Ewing territory. The Deep Purple bassist was just focused on becoming more and more annoyed.

In the first shop, the record hypermarket, the manager persuaded Bolin to climb a stepladder and autograph a six-feet-square, hand-painted cardboard poster of the Teaser album sleeve stuck up high on a wall. Hughes, standing on his own by the record racks, was plainly annoyed by all the attention his Purple colleague was receiving. And in the second store Hughes’s irritation turned to outright anger.

A banner outside the dedicated hard rock shop was emblazoned with the words: ‘The Teaser on Nemporer Records – here in person, today, 6.30 thru 7.30’. No mention of Deep Purple or Glenn Hughes whatsoever. The whole of the store’s main window had been given to Bolin publicity material. A Come Taste The Band cover was displayed unceremoniously in a smaller window, alongside many other, lesser album sleeves. Purple’s record was being completely overshadowed.

In the limo, on the way back to the hotel, the atmosphere remained tense. I don’t think Bolin or Hughes exchanged a single word during the journey. So it was no surprise to me when a perturbed Hughes declared to me later that evening: “I don’t like heavy rock music. But Smoke On The Water and all that is Deep Purple… I can’t change it. I don’t feel frustrated when I’m playing, but I do sometimes when I’m off stage and I begin to think about it.”

And Hughes certainly had plenty of time to ‘think about it’ off stage during those Dallas record store appearances.

Glenn Hughes today: “Tommy was pissing a lot of people off. He was pushing his Teaser album, and I totally get that. But what was happening for me in 75 and early 76, I’d lost my battle to control my addiction. I didn’t know it until later on, and I was destined to go down the wrong road. So it was painful for me, working with my so-called brothers in a situation where I was going off the rails.”

After all that gloomy stuff, it might surprise you to know that I returned to Britain full of positive thoughts about the Tommy Bolin line-up of Deep Purple.

At the beginning of my sojourn in Texas, Jon Lord had remarked – in a world- weary way, and while nursing a glass of Cognac – that he was making his 24th visit with Deep Purple to the USA. At the end of my article in Sounds I wrote: ‘At least that 25th American tour is assured’. Little did I know that it would be without Bolin.

Back in the UK, my upbeat mood stemmed from the last gig I saw the band play during my visit to Texas – number four on my list of memories. It was a mightily impressive show.

The location was Houston, a space-age place full of cloud-caressing towers clad with unblemished tinted glass. But the venue for the night’s gig provided a stark contrast to the Mr. Sheen city. The Coliseum may have been a huge, outdated, grimy hall packed with crazy cowboys, but it was the ideal setting.

From my vantage point high up on Purple’s mixing desk platform, the Coliseum’s pistol-packin’, herd-’em-up-and-move-’em-out atmosphere seemed ideally suited to a downhome rock’n’roll event; much more so than, say, than the concert venues I had visited previously on this tour. Abilene, for example, was a colossal, Teletubbies-style edifice stuck out with the coyotes in the middle of nowhere; Fort Worth was an imposing, clinically clean baseball stadium.

In Houston, Deep Purple were a band transformed. And it was all thanks to a certain Thomas Richard Bolin.

Until now, my main criticism of Bolin had been that in past shows he had seemed reluctant, almost afraid, to assert himself. I think I wrote in Sounds that he wasn’t ‘flashy’ enough. By which I meant that he struggled to flaunt his playing expertise, inflate his ego, puff up those American Indian feathers he used to wear in his hair and say: “Hey, I’m Deep Purple’s new guitarist. I’m a damn sight better than Ritchie Blackmore. You don’t believe me? Here, I’ll show you…”

As opening number Burn progressed, Bolin still seemed content to play a low- key role, and looked unwilling to unleash the power at his disposal. But something helped Bolin’s cause that night at the Houston Coliseum. The show was loud. Bloody loud. The loudest concert so far, in fact. During the first song, the Scottish guy in charge of the mixing-desk controls leaned up close to me and bellowed, still maintaining his distinctive north-of-the-border burr: “There’s a bit of power in those speakers tonight, eh? This is the real Deep Purple.”

And how right he was. After Burn, a selection of new songs from Come Taste The Band followed: Lady Luck, Gettin’ Tighter – which was the US single – and Love Child. Bolin looked more at home with the newer numbers and began tostrut a little, some of his cool off-stage manner beginning to seep through. Predictably, the biggest cheer of the evening came with the announcement of Smoke On The Water. Bolin, getting more self-assured by the second, had the balls to corrupt the famous opening chords slightly (would he be able to get away with that in Britain? I wondered) and add an extra twangy note or two.

But it was probably at this moment that, for the first time, I managed to accept Bolin as Purple’s new guitarist. Yes, it was strange to hear him mangle such an almost sacred riff, but it was also daring and audacious. The secret was, Bolin somehow made this quintessentially Purple song his own.

And so to Bolin’s long-awaited solo spot. Billed as ‘the best new guitar player in world’, he finally, successfully, proved equal to the hyped-up introduction. Bolin’s past solos – and I think you can guess the reason why – had been at best mundane, at worst bordering on the incompetent. I had found myself wondering on more than one occasion whether the guitar-playing tornado on Spectrum and the guy struggling to eke out the simplest of Deep Purple licks on stage had been one and the same person.

But Bolin’s Houston solo was both belligerent and brilliant; a heavy rock workout par excellence. It began with some ingenious use of Echoplex, ebbed and flowed through some deft, sensitive picking that recalled the quieter moments of his Teaser album, and climaxed in an orgy of six-string strangulation. The crowd grew increasingly responsive, and Bolin, gaining in confidence, shook his pale fist at them, then made a gesture for more applause – and received it in spades. Even from the mixing desk you could see Bolin’s eyes glimmering with pleasure as he realised abruptly that the audience was his; his to shape and fashion, his to silence or inspire to rapturous cheers.

That night in Houston, Bolin hit the pinnacle of his Purple powers. He truly lived up to the slogan on his T-shirt: The Ultimate.

Glenn Hughes today: “Regardless that Tommy died young of drugs, I still remember him being like a brother to me. I loved him. You knew Tommy, Geoff. He was sweet, kind, but riddled with drug addiction. Did I know that he was a heroin addict? No. I was na?ve. Did I know that he was on morphine in Indonesia? No. I just knew he was a sweet guy.”

This was originally published in Classic Rock issue 58, in October 2003.