The Making of 'Captain EO': Lucas, Coppola, and Michael Jackson's Messy, Miraculous Disney Space Adventure

Michael Jackson in ‘Captain EO’ (Disney)

By the mid-1980s, the Walt Disney Co. was at a crossroads. While the entertainment conglomerate was still beloved for its classic films and theme parks, it had struggled in recent decades to retain its relevance in the post-Star Wars blockbuster era. Ever since the death of the company’s namesake founder, Walt Disney, in 1966, the studio had churned out only a handful of hits (including The Love Bug and The Rescuers) and no shortage of expensive duds, like Black Hole and Dragonslayer. In 1984, one of the studio’s theatrical hits was a reissued version of Pinocchio — a movie that was by then more than four decades old.

Enter former Paramount CEO Michael Eisner. The well-respected exec had been hired to take over Disney and given the daunting task to reverse its sagging showbiz fortunes. One of Eisner’s first ideas was to bring the company’s disparate divisions — movie production, theme parks, and engineering — together for a high-profile project that could showcase its collective might. Together, they came up with Captain EO, a big-budget 3D sci-fi short film that would star Michael Jackson — who, two years after the release of Thriller, was arguably the biggest star in the world. The ambitious, highly publicized mini-movie would play exclusively at Disney parks, and would serve as an announcement that the company was about to enter a new era.

Disney went all-in on the project, bringing in producer George Lucas and director Francis Ford Coppola for what was essentially a multimillion dollar 17-minute-long music video. The plot featured Jackson as a space captain battling an evil queen (Anjelica Huston), while surrounded by a crew of furry, goofy alien puppets and robots right out of the George Lucas interplanetary comic relief playbook. The cutting-edge project — perhaps the most highly pedigreed film to ever feature a farting space elephant — would eventually balloon in cost (with a final budget of somewhere between $17 million and 30 million) and eat up unexpected production time. When Captain EO finally opened at Disneyland in September 1986, EO had achieved the distinction of being, on a dollars-per-screen-minute basis, the most expensive film ever made.

In November, Disney announced that Captain EO — which has run at four parks over the last three decades — would shut down on December 6, replaced by new Pixar and Disney attractions. The show could always be revamped, of course, but if this truly is the end of EO, it’s a decidedly anticlimactic ending to a remarkable and strange story: Never before have so many major talents — including the makers of Thriller, Star Wars, and Apocalypse Now — been brought together for a movie as ambitious as it was silly. This is the story of Captain EO, and all the behind-the-scenes trials, tribulations, and tickle-bouts it entailed.

PART I: The Godfather, the Jedi Master, and the King of Pop

In 1985, Michael Jackson could be anything he wanted — and he wanted to be a movie star. His adviser, record executive David Geffen, suggested the singer meet with Disney. Jackson had a deep love for the company’s theme parks. He owned a suite at Disney World’s Contemporary Resort Hotel — complete with its own staff — and Disneyland was often opened after hours so he could enjoy it privately with his friends.

Michael Jackson (from his 1988 memoir, Moonwalk): Disney Studios wanted me to come up with a new ride for the parks. They said they didn’t care what I did, as long as it was something creative. … In the end, they asked me to do a movie, and I agreed. I love the movies and have since I was real little. For two hours you can be transported to another place. Films can take you anywhere.

Rick Rothschild, then working for Disney’s in-house theme park engineering team, was given one week for him and his crew to come up with concepts.

Rick Rothschild (Disney Imagineer): One of the [movie] ideas was The Intergalactic Music Man, [in which] the world was all cold and awful, and [Jackson and a team of creatures] come and help [everyone] understand that life is better when it’s all colorful and warm. The second [idea] focused on our understanding that Michael loved various characters and attractions around the park and movies — Peter Pan was one that he was fond of. So we developed a fantasy that was somewhat similar to The Music Man idea, but focused on a band of characters that were more fairy-like and fantastic. We knew that Pirates of the Caribbean was an attraction [at Disneyland] that he really loved.

Jackson (from Moonwalk): Pioneering new ideas is so exciting to me, and the movie industry seems to be suffering right now from a dearth of ideas. So many people are doing the same things. … So many of them are doing the same old corny stuff. George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are the exceptions.

Jackson wanted Lucas and Spielberg to produce and direct the project, and Lucas agreed to oversee it. But by the mid-’80s, Lucas’s attention was focused on a number of projects, including Indiana Jones and his effects company, ILM, so Disney hired Rusty Lemorande — who’d recently written and produced the computer-centric comedy Electric Dreams — to oversee day-to-day production. But EO still needed a director. Jackson had requested that Steven Spielberg direct the project, but he was unavailable, so Lucas brought aboard Francis Ford Coppola, his old friend and mentor, who was coming off a rough box-office run, thanks to back-to-back flops Rumble Fish (1983) and The Cotton Club (1984).

Rusty Lemorande (producer): I think it’s fair to say that Francis got the job because of George. I think George was very proud to be able to do that for his friend.

Francis Ford Coppola (director): There was a period in my career when I had gotten into financial trouble over One From the Heart [1981]. I was in a tough, pseudo-bankruptcy situation. I had to do one movie after another to pay the bank and get them off my back, which I eventually did.

Harrison Ellenshaw, who was in charge of creating many of the groundbreaking space backgrounds in the Star Wars films, was brought in to be Captain EO’s visual effects supervisor.

Ellenshaw: Disney was known for its effects — look at Mary Poppins, and all the incredible work for the parks. But they were behind the times. Nobody outside of Disney came to Disney to have their effects done, and that was a big issue for this new regime. They wanted to be such an important player that they [would attract] outside business. I had come off of working on Tron, and I had a little bit of a positive reputation. I remember my first meeting with Francis. I said, “I have to admit to you: I’ve never supervised or done effects in 3D.” And he looked at me and said, “Neither have I! Let’s go do it.”

Coppola: Some projects, like Captain EO, I didn’t have a hand in creating — I had suggestions. Michael Jackson had an idea, and George Lucas had an idea, and Disney had an idea. [So] the director was more someone who took all the fragments that everyone thought of and did the best they can. It’s a lot different than doing something that comes form your own being; you constantly negotiate. When I first thought about [Captain EO], I didn’t know what sense to make of it.

Coppola, Lucas, Jackson, Lemorande, and Ellenshaw — among others — met at Lucas’s office in San Anselmo in April 1985, to revise and finalize the film’s title and story.

Ellenshaw: The title of the show was Space Knights at that time. Francis started to talk about the main character that Michael would play. He didn’t have a name or rank yet. Francis related how the word “Eos” meant “dawn and light” in Greek. And something like that would fit a character who comes to a dark, ugly planet ruled by an ugly evil queen, and change it all with song and dance and magical light beams that transform everything into great beauty. “Eos” was shortened to “EO,” and then it was decided to give the character the rank of Captain.

Lemorande: Michael was very intense about the evil queen — he wanted it to be very scary. He really believed that kids loved scary entertainment. He loved Alien, he loved Snow White. The scarier the better. Shelley [Duvall] was the first choice to play the Queen. The makeup people met with her to put on the plaster casting.

Terri Hardin, (puppeteer): When they went to do the face cast for Shelley, they were going to do pretty much a three-quarter-to-full makeup. She was claustrophobic, and couldn’t handle the process.

Lemorande: She expressed a sudden disinterest in doing [the movie]. The next idea was a far less important actress: Anjelica Huston. She wasn’t that big of a deal at the time. She didn’t have a breakout hit. It was very easy to get her because Francis and George were a big deal.

Anjelica Huston (evil queen): I’m a little bit psychic. I had a dream about a month before I was offered this movie that I was having a wonderful love affair with Michael Jackson. And we were in a desert and we were suspended [in the air]. He was suspended, parallel above me in a landscape, and we were just sort of floating there in midair. And behind us, a stampede of elephants came to us and made a tunnel with their trunks around us. And this was a very impressive dream, one of those that you wake up from and go, “Whoa, what was that?”

A month later I got the call to do Captain EO. I remember being on set, and Michael had a little green elephant friend in the show called Hooter, and I remember going, “Oh my God, I had a real foretelling dream about this.”

Around the time Huston was offered the job, she won raves for her performance in Prizzi’s Honor (which would later win her an Academy Award for Best Actress). Prizzi’s Honor debuted in early June, weeks before Captain EO began shooting.

Lemorande: We suddenly had a way bigger star. She became famous very quickly after Captain EO. She didn’t have an Oscar before we hired her. If she had an Oscar before we hired her, I’m sure she wouldn’t have done the job.

Huston brought with her another important change.

Lemorande: The original idea was Michael’s transformation of the witch would turn her into a beautiful woman, the traditional kind of Disney thing. We cast a beautiful black girl who was transformed from Shelley Duvall, and that would work, everyone would know it was a fantasy. When we changed it to Anjelica Huston, it didn’t make sense, it didn’t work. So we said, the evil queen can transform into a beautiful version of herself, with makeup and lighting and all of that.

On their first day together, Coppola had his actors improvise in order to get comfortable together. He separated them and whispered their own “secrets” to them, and then tossed out scenarios for them to play out.

Hardin: Francis comes over to [the performers working with the alien puppets] and says, “[In your scenario], you guys are going to be the kids at a camp.” Our secret was that, under no circumstances were we to listen to Michael at all. Michael’s secret was that if we didn’t behave, he could be fired. Anjelica’s secret was that she was the owner of the camp and her goal was to fire him. And so, “Action!,” off we go. [Michael’s] standing above us, and we’re pulling on him and laughing like kids. And he’s going, “Please, I could get fired! Behave, behave!”

[Anjelica] takes one giant step and says, “Michael Jackson!” He stiffens up like a board and starts to shake, and she walks over to him very slowly, picks him up by his shirt, and lifts him up about 10 inches off the ground. And she pulls his face toward her face and says, “You insignificant little worm! You’re fired!” and she throws him back across the soundstage, and he falls on his butt.

Huston: In rehearsal, he was so shy. He found it very hard to express anger.

Rothschild: [EO’s companions] were the classic band of misfits. A lot of that was early on, very clearly conceptually laid out. Then there was a lot of work that went on between Francis and Michael and our team to develop the characters.

Lemorande: I came up with Hooter, because I’d always loved elephants. When I was a kid, I had a fantasy miniature elephant and I made him, in my mind, crawl up my pencil and live in the inkwell. So it’d be a small elephant, but he’d play his nose like a reed instrument — I used to have a bagpipe, so I said I’d make it sound like a bagpipe.

The puppets were not very complicated. The only one that was complicated was Fuzzball, which was moved with cable, and that was done by Rick Baker. Michael just loved that character so much and wanted that character to get as much screen time as possible.

Rick Baker (puppet designer): [Lighting consultant] Vittorio Storaro decided at the last minute that the aliens should all be like the colors of the rainbow, and they wanted Fuzzball to be red. And he wasn’t made red initially; we made him a natural color. So at the last minute we had to paint him red, which I wasn’t too pleased about. But it was just that one character. I was on the set for a day or two but I don’t have a lot of memories of it.

Kirkland: Michael loved the creatures. He was more fascinated with those than anything, really. When we were up at our meeting at George’s place, he was looking at the characters. They were like toys to him.

Jeff Hornaday (choreographer): [Michael also had] a real playfulness. I remember we were up at the Lucas ranch while they were editing, it was just us going over footage and sequences. I looked over and Michael was giggling. And later, I went to the bathroom and I looked at my back and there was a piece of paper taped to me that said, “Please kick me in the ass.”

Hardin: One day, we were both sitting on the steps, eating our lunch, silent for a little bit, and I say, “Michael, let’s pretend I’m a genie. I come down to earth and say, for all your goodness and kindness, I want to grant you three wishes. So what would they be?” And Michael thinks a little bit and says, “Wow, nobody’s ever asked me that before.” And then he says, “Well, my first wish would be to have my childhood.” And for wish No. 2, he said he would like to go to a mall without having to buy it.

PART III: Lights, Camera, Dancing

Captain EO began filming on July 15, 1985 on a soundstage in Culver City, California. Though it was only a short film, and not nearly as epic on the scale of, say, Apocalypse Now, Coppola approached the production with a number of grand ideas.

Ellenshaw: It was the first day of production, and Francis had insisted that we put the interior of the spaceship on a gimbal [with] big hydraulics. And rather than shake the camera, we’d shake the whole gimbal. It was hugely ambitious, and cost a crap-load of money. You have to raise [the gimbal] up, get these hydraulics underneath it, and pump pumping water in and out to make it go down.

Peter Anderson (cinematographer): As Michael starts to rise up, the ship lurched and then tilted precariously, and then the lights start going out. One of the high-pressure lines had ruptured, and it was hosing down the whole stage. Michael got hurt, pinched his hand in an elevator. He went to the doctor. After lunch, Michael was back and said he was fine, and he said let’s continue.

Lemorande: [Michael] was as dedicated as any filmmaker, any artist, any dancer, any ideas guy. He was in The Wiz years before, but he hadn’t come into his own [as an actor]. That’s all he talked about: He wanted a film career. He was really tired of doing the videos.

Anderson: [Captain EO] was a closed set, but the A-listers were always there. Warren Beatty, Sophia Loren, [or] Elizabeth Taylor would come in, to the point where there was a barista to make sure they got their afternoon coffee. Elizabeth Taylor walked up and started to talk to Michael, and when he was strapped in to the body pan [for a flying stunt], she started tickling his feet.

Huston: She had a notoriously bad back from a fall on National Velvet when she was a kid, and I remember her turning to Michael during my one moment off, when I was on the floor with him, and she said, “Michael, you should have given me [Anjelica’s] part.” Like hell [she] would have done it! [laughs]

Jackson wrote two new songs for the film, one of which, “We’re Here to Change the World,” was used in the climactic stand-off between Captain EO and the queen, and culminated with Jackson leading an army of dancers.

Kirkland: I remember going up to George’s house with Michael — we flew on a regular jet, believe it or not. Francis was there. He and George were great old buddies and chatting away and chatting away, and poor Michael didn’t know what to do with himself. He was standing in the corner wondering why he was there a little bit. He was very quiet and incredibly shy. Then Francis asked “Where are we on music?,” and Michael suddenly lights up and goes on and on.

Huston: I’ll never forget this moment [during the shoot]: He’s on a platform and, as it happens, the platform rises. And I kind of dip in the shot, just sitting there and watching. Playback starts, and something happens to Michael and I swear, I gasped. His transformation from the Michael I’d been rehearsing with — who was a little shy and giggly and retiring — all of a sudden, the power of him, when he was singing, was something so extraordinary. My jaw dropped. [Performing] was the full expression of who he was. All other times, he was at half speed.

Coppola: I knew I wanted the big dance at the end to be more integrated with the story, rather than [the movie] be this short little dumb story and have a music video tacked on the end of it. But Michael Jackson was really wily, and no one knew what the music or song was going to be until the time that they did it. He felt he didn’t want the dance to be integrated within the story. So we shot this little story, and then he came and had the song, and we did it the best we could. [The dance number] was tacked on to the end. I thought it should have been more integrated into it. But I found Michael [to be] very sweet, and I was fond of him. He was like a big kid.

PART IV: Auteurs in Outer Space

There was a wealth of talent on the set of the film, which led to groundbreaking work — but also some difficulty. Everyone had strong opinions (and other projects) vying for their attention, which slowed down Captain EO considerably.

Anderson: Every day, we start with a plan and at the end of the day, you try to figure out what that plan was. … I was the DP, but after Francis came on board, he wanted to bring on Vittorio as a consultant, and he was the lighting director. And Vittorio is a wonderful creative person, but he had never lit live-format 3D. So sometimes it was a little bit of a strain. We were shooting in 3-D, which requires more light; we were shooting in 30 frames-per-second, not 24, which is a better rate to get Michael dancing. Each one of these required more light. There were lots of little things I was doing just to make it more viable without trying to get into a disagreement.

Ellenshaw: George Lucas had good intentions. After Jedi came out two years earlier, he said he was exhausted, [and] needed to take two years off. Which he did, but when he came back into doing stuff, he was very ambitious, and that’s George’s nature. So he had not only Captain EO to worry about — he [also] had ILM to worry about, he had a computer division — which was later to become Pixar — going, he had Star Tours, he was building stuff out at the ranch, and he went through a divorce. So he could never give Captain EO or any of the other things full attention. So it’s kind of like having Michelangelo come by every other day for half an hour and telling you, “If I had the time, I’d do the Sistine Chapel, but since I don’t, let me tell you what you need to do.” And then he’d wait two days, and then he comes by and says, “You didn’t do it right, do this, do that.” Everything was constantly in flux.

Lemorande: George wanted the set dressing to look more used. One of the things he did with Star Wars originally that was very avant-garde was that it was a “used future.” Fabrics were tattered. Moving vehicles had rust patches on them or black patches from the emissions of the energy source. There were junkyards. Prior to that, everything in space was sparkling. So we beat everything up, made it like a space trailer park.

Ellenshaw: There two models [for the ships]. We had built them, we had shot them, and they were in the can. And then George decided, “I don’t like the designs.” All of those got dumped, and [Star Wars designer] Joe Johnston made two new designs, which were really cool. ILM basically went and shot the designs that Joe had done.

The 3D technology for EO was groundbreaking, but also led to a rather deliberate produciton.

Kirkland: I’m sure Francis might have been a little frustrated because it was taking longer because he cared, but when he gets into something, he’s 100 percent there.

Anderson: Francis brought his Airstream trailer with him. It had a lot of tape decks and [editing equipment], and a hot tub. So once or twice during the lunch hour, I was invited to join Francis, who was soaking in his hot tub watching dailies, and also watching audition tapes for Peggy Sue Got Married, which was going to be his next feature.

Lemorande: We knew we had Francis for two weeks of shooting, because he was scheduled to do Peggy Sue, and that was a firm start date.

Ellenshaw: We needed a union supplemental director to [direct a second unit at night]. Francis said, “My son Gio [Gian-Carlo] is a member of the DGA. He’ll do it, and Harrison and others will help him.” You could tell that Gio had inherited some genes somewhere.

Anderson: If it’s a Coppola, there’s film and wine running through their blood. Gio knew what he was doing, [and] he was easy to work with, he was great. Francis was great too, don’t misunderstand that. But Gian-Carlo [seemed] more interested in what we were doing.

Ellenshaw: On occasion, Michael would stay late to help get some shots. We would usually finish by midnight.

Anderson: At about 5 o'clock in the evening [on the last day of Coppola’s shoot], production manager John Romeyn went for a break. These tables come out and a fully catered dinner comes out for us. … This was a nice soirée. And then at the end of the meal, Francis and Vittorio said, “Thank you, everybody,” and they left.

I didn’t expect this, nor did anybody else on the crew. But that was the end of the 14th day of principal photography. Then we cleared the tables out of the way, we reset the actors, redressed the floor, and Gian-Carlo took over directing the first unit.

Ellenshaw: Francis kind of stepped away. [He] didn’t want to get involved too much in the politics, and was happy to have his name associated as long as it came out decent. But that dynamic basically delayed the postproduction period, which eventually became nine months, and the release date kept being postponed. You’re spending a lot of money, you’re making a lot of changes, and it became chaotic and extremely stressful for all concerned.

Ellenshaw’s initial budget, submitted in September 1985, provided for 40 effects shots and put the film’s final cost at around $11 million. By January 1986,EO had grown to include nearly 150 effects shots, and the countless revisions and additions meant the film’s original $11 million budget would soon begin to swell too.

Ellenshaw: [Captain EO] took years off my life. The studio said, “We can’t allot more money to this. In fact, we think you’ve spent too much already, so we’re not going to spend any more money.” Which is typical of any business anywhere, unless you’re being financed by an oil-rich megalomaniac.

I was in a situation where they said, “We want something no one has ever seen before … but we don’t want to pay for it.” In a nutshell, we went from great hopes, great ambition, to more hopes, more ambition, less money. By the time we were at the end of production, we were starting to descend into madness, because it was so illogical. It was so crazy.

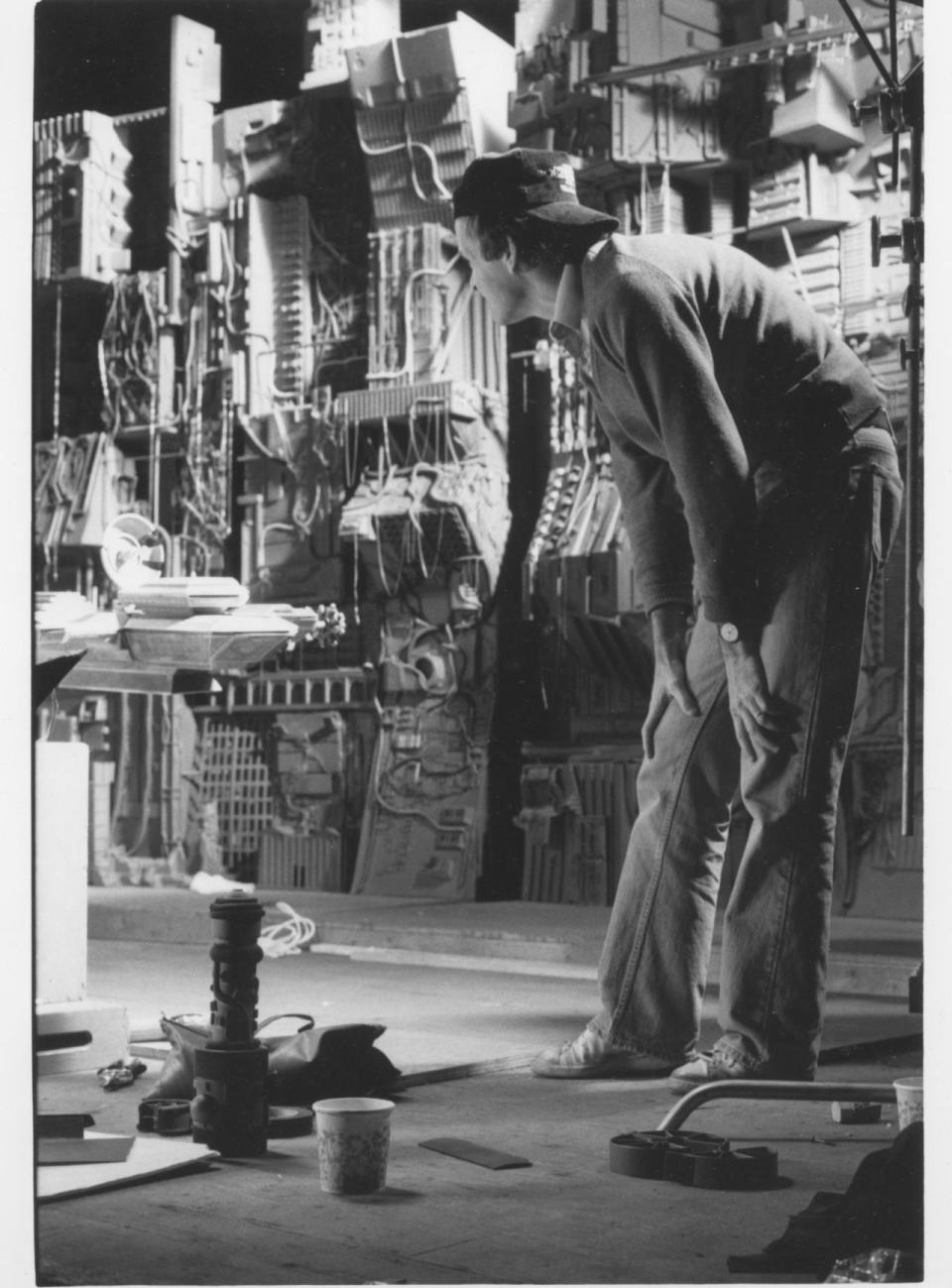

Photo courtesy Harrison Ellenshaw

Anderson: George was involved in pre-production; he would offer support and creativity and input and so on, but he was just sort of there as a Grand Poobah, basically. It was interesting because it wasn’t [initially] an ILM project, and it wasn’t something he was familiar with and he wasn’t directing it, but he was the supreme leader consultant on the project.

Ellenshaw: George would show up a little bit more often in [postproduction than in production], but not enough to really help you and guide you. When I was working on Empire, George would come by every day and look at dailies, so it was easy. You did the best job you could, you showed it to George, and he’d say “change this” or “change that.” But during EO, it was more like, “Is George coming by this week?”

Disney was also starting to have some reservations about their big star.

Anderson: Michael had a propensity to do his crotch-grabs. It was kind of unheard of back then, and this was Disney. I was told to crop the upper torso or go for a tighter shot or something like that, [but] they were part of his routine. So it wasn’t like [he was only] occasionally doing it. It was on his beat. Disney started cutting [the film] together and saying, “Oh dear, oh dear.”

Ellenshaw: The whole issue was pretty silly, even at the time. [And] the editor could work around crotch-grabs without a problem. But this was a [movie] that would be shown to families at Disneyland, and the new management was especially aware that some people might find a dancer grabbing his genitalia as being offensive.

Anderson: [Michael also] had a rather high-pitched voice. People weren’t used to hearing him talk — they were used to hearing him sing. The studio was trying to figure out how to modulate or replace his voice for the talking scenes. There were groups of people at Imagineering and some at the studio that were afraid that that would make [EO] feel too comedic. There was some playing around with [the idea of] changing the octave. There was even a discussion about doing voice replacement for him… There was a whole thing going on in the background of, “How do we do it and not offend him?” And I remember sitting there and saying, “You’re actually going to change Michael’s voice?” They desperately wanted to, but no one had the guts to approach him on it.

Ellenshaw: When we got to the end of the [movie], it screened at Disneyland for all the bigwigs. Back then, [that] included a lot of Disney execs in charge of everything from the theater design to the color of the paint on the outside of the building. Suddenly everybody’s a critic, telling me what to do, even though they were never part of the process. I felt like saying, “Hey, tell you what: You stick to picking the material for the upholstery on the seats, and I’ll stick to the visual effects.”

This was a juggling act of immense proportions. I would have people come to me who clearly weren’t that technically savvy with outrageous demands, and I had to go, “No. I can’t do it.”

Harrison Ellenshaw on the set of ‘Captain EO’

The diverse opinions and demands stemmed in part from the fact that the crew wasn’t just making a movie; they were also designing and building an entire theater that would operate in sync with the film’s effects, with rocking seats, smoke-covered aisles, and zipping asteroids projected overhead. That meant constant tinkering.

Ellenshaw: Rusty was getting kind of nutso, coming up with new ideas. I think it was a reaction to the desperation. He went off and he cut his own version on Betamax, which [Captain EO editor] Walter Murch was not very happy about. Rusty thought he had the magical solution — he was hoping a wizard of 3D would come down from the sky, and every now and then he’d come up with an idea that didn’t make sense. [Update: After the original publication of this piece, Lemorande emailed us to say “The video edit, including animatics for additional photography, was an essential part of the completion of Captain EO.”]

Lemorande: This [film] was, in its moment, revolutionary. We kept getting new ideas that were really cool, and that would require budget increases. So we would have to go Disney and pitch and hold out our hat.

Ellenshaw: Jeffrey Katzenberg — who was in charge of this the whole time, until the film was released — he kept saying, “No more, no more, no more.” And George Lucas kept saying, “I want more. I want this changed. I want that changed.” Who’s to argue with George Lucas? He seemed to do pretty well at this point in his career about being able to do it that way. So he leverages with his power and reputation with the studio by saying, “I’m not happy with it yet, I need more money to do this and that.”

It was up to Peter and myself and others to keep filling in and adding pieces to the puzzle. We were reinventing the wheel in a lot of ways, and I can’t give enough credit to so many people who went out of their way and made the impossible possible. It was pretty stunning

Eventually, Lucas brought in Tom Smith,the legendary Star Wars special effects maestro, and other ILM staffers to help finish the job, and EO wrapped production in May 1986. But by then, the movie was way over-budget — though no one knows for sure by just how much. Some estimates claim it came in around $17 million, others point to a figure as high as $30 million. By the time the film’s fall of 1986 opening date was released, everyone in the Magic Kingdom — as well as in Hollywood — was wondering the same thing: “Will anyone show up to see Captain EO?”

PART VI: EO Takes Off Without Its Captain

On Sept. 18, 1986, Huston sat in a convertible riding down Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A., leading a parade in celebration of Captain EO ’s opening. Coppola and Lucas were also at the premiere, which was attended by a quintessentially ’80s assortment of celebrity guests, including Alan Thicke,, Charles Bronson, Jackie Collins, Dolph Lundgren, and original Mickey Mouse Club member Annette Funicello (O.J. Simpson was there too). The more than 2,000 onlookers in attendance were treated to music performances by the likes of Belinda Carlisle, Starship, and Moody Blues — but Jackson, who had recently taken a year away from the public spotlight, was nowhere to be found

“When Disneyland Debuted His 3-D Movie Marvel, Michael Jackson Was in Another Dimension” (People magazine, Sept. 29, 1986): After photographs of Jackson sleeping in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber had appeared earlier that week, some jokesters suggested that he was too tanked to show up.

Michael Eisner (speaking at the Sept. 18 event): Michael Jackson is here. … But he is disguised either as an old lady, an usher, or an Animatronic character.

Huston: Michael never showed. I think La Toya was there. It was sort of eye watering to go down the main street of Disneyland in a horse carriage, a little embarrassing. It was lonely not to be there with Michael. I don't’ know where he was, or why he didn’t show up that day.

Rothschild: Talking to George before we opened, one of the questions I asked him was, “What was this experience like for you guys, now that we’re on opening day?” And he said, “We had no idea what we were getting into.”

“Close Encounter of the 3D Kind in ‘Captain EO’” (Los Angeles Times, Oct. 9, 1986): For all its wondrous imagery, Captain EO is nothing more than the most elaborate rock video in history: Like a hollow chocolate Easter bunny, it’s a glorious surface over a void. No one expects an amusement-park diversion to be Gone With the Wind, but given its production team credits and the film’s lavish budget (rumored to be between $15 million and $20 million, although Disney refuses to release any figures), audiences have a right to expect more than empty flash.

Still, while critics weren’t wowed by the film, many audience members connected with Jackson’s outer space tale.

“‘EO’ Preview Wows Audiences at Disneyland” (Los Angeles Times, Sept. 14, 1986): During one of several preview screenings, the audience “ooh-ed,” “aah-ed” and broke into applause several times at the numerous elaborate special effects, costumes and intricate sets. … Exiting the 17-minute attraction, audience members praised the film with one-word descriptions like “brilliant,” “outstanding,” and “genius.”

Jeff Heimbuch (author, Main Street Windows): I first saw it in 1988 or so, the first time I went to Walt Disney World. I was 5, so pretty much the entire experience to me was mind-blowing. Something about seeing a 3D film, set in outer space with zany characters and musical numbers, was just some more icing on the mind-blowing cake.

EO was an incredible achievement for Disney. Not only was it a full-fledged sci-fi film, but it featured some top talent and some exclusive MJ songs, and the only place you could get to see it was in the parks. It was a coup, and I think in a lot of ways, it helped inch the Disney parks more into American pop culture during the ’80s. It wasn’t just for kids. It was edgy. It made it OK for some people to like Disney.

Disneyland was open for 60 hours during EO’s first weekend, with the film playing on a continuous loop. The park took in $2 million at the gate that weekend.

Ellenshaw: At the end of the day, it was a huge hit. 93 percent of the attendees said that was their reason to visit Disneyland. It was a phenomenon.

Captain EO wound up running at Orlando’s Epcot until 1994, and screened at Disneyland from 1986 to 1997, — at which point Jackson’s scandals had alienated some of his fanbase. But the outpouring of grief that occurred after the singer’s death in 2009 led Disney to return Captain EO to many Disney parks the following year. When it closes this year, EO will have run for nearly two decades and in four locations.

Heimbuch: Disney pushed the limits of theme-park entertainment, [with EO] and opened the gates for collaboration between other intellectual properties and outside people. I think, in a lot of ways, we wouldn’t have Star Wars in the parks if it wasn’t for EO.

Anderson: They were taking a certain amount of risk with this project. [Michael] was a pop icon, but Disney at the time wasn’t built on pop icons. They wanted to make sure that Grandma and Grandpa would like the show, too… Imagineering is about presenting people and taking them to different universes using technology. The studio is about entertainment, Michael is about song and music, and this combined the best of all three of them. There had been nothing out before that came anywhere close to this.

Captain EO will stand alone. It’s not the greatest movie ever made, but it’s a great musical piece, up there with Thriller. And it’s survived the test of time.

Note: This story has been updated since its original publication.