“It Was Like Starting All Over Again, Like I Had Never Played the Guitar Before”: Tired of Recycling the Same Old Blues-Rock Riffs and With Nothing to Lose, Jeff Beck Turned to Jazz-Rock Fusion

In 1974, Jeff Beck found himself in a repeating cycle that rivaled the predicament of Bill Murray’s character, Phil, in the movie Groundhog Day.

After being booted from the Yardbirds in late November 1966, Beck formed three different bands – two iterations of the Jeff Beck Group, and the power trio Beck, Bogert & Appice – that enjoyed moderate popularity primarily as touring acts.

But no matter how much Beck varied his approach with the three bands, the outcome was always the same. Each managed to release two albums (in BBA’s instance a studio and a live album), but none of those records delivered any hits, and commercial success remained elusive.

All three groups lasted only a few years before Beck became frustrated or disinterested in the projects and moved on. Work on the second Beck, Bogert & Appice studio album began in January 1974, but that May, Beck pulled the plug before it was completed and disbanded the group.

The guitarist had grown tired of recycling the same old blues-rock riffs and licks he’d been playing for most of his career, and realized that he needed to make a radical shift in direction, if only to preserve his own sanity.

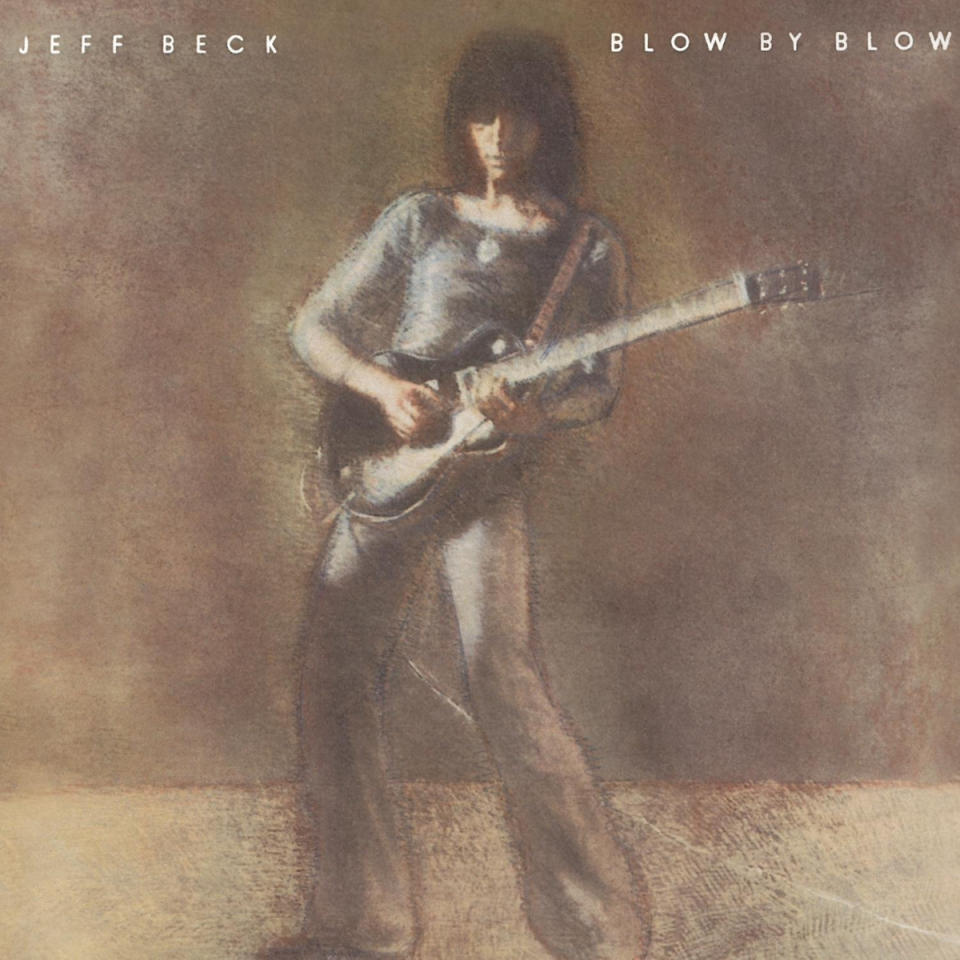

The music that excited him the most during this period came from the burgeoning jazz-rock fusion movement, and he soon found himself pulled in that direction. Following his fusion muse, Beck recorded Blow by Blow, his first entirely instrumental solo album, which was released in March 1975.

To Beck, his journey into jazz-rock fusion made perfect sense as he considered it a logical progression of rock music. “A handful of tapes knock me out,” he said in the November 1975 issue of Guitar Player, “things like Billy Cobham, Stanley Clarke – all the great rock and rollers. I call Billy Cobham a rock and roller because he’s so forceful. Rock’s an energy to me. It’s more complex now than it was, but it’s rock just the same.”

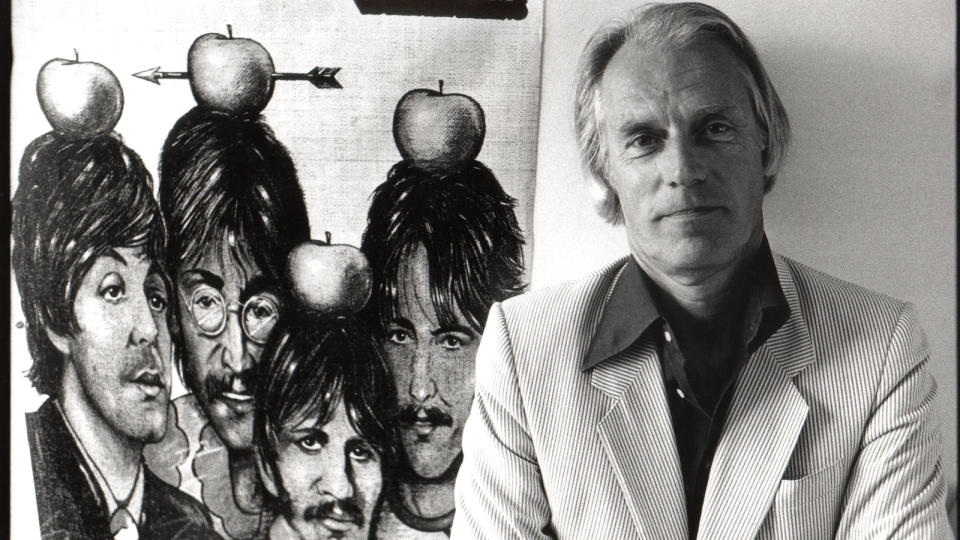

In addition to Cobham and Clarke, Beck was highly impressed with the work of his good friend guitarist John McLaughlin and his band, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, particularly their recently released album Apocalypse. Indeed, Beck’s decision to hire George Martin to produce Blow by Blow was influenced almost entirely by Martin’s work on that album, and not the producer’s legendary work only a few years earlier with the Beatles.

Beck entered London’s AIR Studios in October 1974 accompanied by keyboardist Max Middleton, his former bandmate in the second version of the Jeff Beck Group, and session players Phil Chen on bass and Richard Bailey on drums. Stevie Wonder, in addition to writing two songs Beck covered on the album – “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” and “Thelonius” – played clavinet on the latter.

“Blow by Blow marked an important change in my life,” Beck said in 1999. “I was exploring an entirely different direction, but it came together almost by accident. I always fed off of singers or guitar riffs before, but Max Middleton kept throwing these beautiful chords at me, and Stevie Wonder had come up with some beautiful melodies, so I had no choice but to follow them. It was like starting all over again, like I had never played the guitar before.”

'Blow by Blow' marked an important change in my life

Although Blow by Blow is hailed by many as a jazz-rock fusion classic, only a handful of songs on the album truly fit that description: “Freeway Jam,” “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” and the orchestral string section-accompanied songs that close each side of the album, “Scatterbrain” and “Diamond Dust.”

Jazz-funk fusion is a more accurate description, as funk plays a prominent role on most of the album, particularly Beck’s rhythm playing on “You Know What I Mean,” with its obvious nod to Jimmy Nolen’s scratchy chords on James Brown’s “Sex Machine,” Wonder’s low-down and dirty clavinet on “Thelonius,” and the relentless syncopated grooves of “Constipated Duck” and “Air Blower.”

With its reggae-inspired feel, the instrumental cover of the Beatles “She’s a Woman” is a bit of an outlier, but Beck’s expressive phrasing makes it fit in.

The funky feel of Blow by Blow was inspired by another often overlooked source, the band Upp, which Beck discovered in June 1973 while rehearsing for his appearance at David Bowie’s Hammersmith Odeon farewell concert.

When Beck heard the band jamming to some James Brown grooves in an adjacent room, he “kicked the door open” and introduced himself. Over the next year, he produced and played guitar on the band’s debut album, although his name didn’t appear in the credits.

Beck’s involvement with Upp became public knowledge when he performed with the band on the BBC’s Five Faces of the Guitar special recorded in August 1974 and broadcast the following month, only a few weeks before he started recording Blow by Blow.

The arrangement he performed of “She’s a Woman” is almost identical to that heard on the album, with the exception of the absence of Middleton’s keyboards. The gear that he used for the BBC broadcast – including his modified 1954 “Oxblood” Gibson Les Paul, an Ampeg VT-40 combo amp, Colorsound Overdriver, Cry Baby wah, ZB Custom volume pedal and Kustom “The Bag” talk box – was likely the main rig Beck played on the album.

He also used two Stratocasters – an early ’70s Olympic White model and one with a stripped-finish early ’60s body and mid-’70s rosewood neck – and his “Tele-Gib” 1959 Telecaster with two PAF humbuckers installed by Seymour Duncan, most famously employed for the Roy Buchanan-inspired performance of “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers.”

Three singles from the album – “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers,” “She’s a Woman” and “You Know What I Mean”– were released in Japan, the U.K. and the U.S., respectively, but all three failed to chart. However, the first two songs, along with “Freeway Jam,” received frequent airplay on FM radio, which helped the album quickly climb to a peak position of number four on the Billboard album chart and achieve RIAA Gold certification.

More than 10 years later, in 1986, Blow by Blow was certified Platinum.

It earned him a new level of respect from his peers, fans and critics, and gave him more creative freedom to express himself

By following his heart instead of prevailing trends, Beck was unexpectedly rewarded with his most commercially successful album ever. But Blow by Blow’s success was much bigger than sales figures. It earned him a new level of respect from his peers, fans and critics, and gave him more creative freedom to express himself with his guitar as the focal point instead of as an accompaniment to a vocalist.

Beck knew that Blow by Blow was going to be a hard act to follow, but it also wasn’t a fluke. Perhaps to absorb even more inspiration from John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, he went on a co-headlining tour in 1975, where Beck’s band – featuring Middleton, drummer Bernard Purdie and bassist Wilbur Bascomb – and McLaughlin’s latest outfit traded opening slots.

Beck gained more than musical ideas from the venture as McLaughlin gave Beck an early ’60s Olympic White Stratocaster that was an upgrade from the ’70s model Beck had been playing for several years.

A nice Strat wasn’t all that Beck got from McLaughlin. When the Mahavishnu Orchestra broke up shortly after completing the Inner Worlds album, Beck poached drummer Narada Michael Walden to play on the sessions for his follow-up to Blow by Blow, replacing Richard Bailey who had already recorded two tracks – “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” and “Head for Backstage Pass.”

Walden’s songwriting skills were as adept as his drumming, and he contributed four songs to the album later titled Wired – “Come Dancing,” “Sophie,” “Play With Me” and “Love Is Green” – and played piano on the latter.

Former Mahavishnu keyboardist Jan Hammer, who left the band in December 1973, also joined the sessions a few months after they initially got underway. In addition to Mahavishnu, Hammer had previously played on Billy Cobham’s Spectrum and Stanley Clarke’s eponymous sophomore solo album, so landing a musician who was heavily involved with all three of the artists Beck appreciated the most during that era was a major triumph. Hammer’s guitar-like synth lines profoundly inspired Beck’s tone and phrasing.

“[Jan Hammer] gave me a new, exciting look into the future,” Beck told Guitar Player in a 1975 interview after the release of Blow by Blow, but before he joined forces with the keyboardist. “He plays the Moog a lot like a guitar, and his sounds went straight into me. So I started playing like him. I didn’t sound like him, but his phrases influenced me immensely.”

“We were very, very similar, even though we were coming from opposite ends of the musical universe,” Hammer said in a 2020 interview. “He was a rock icon, a rock and roll giant, and I was a pretty well-known modern-jazz musician, but I was trying to get more into rock and he was trying to get more into jazz. We met right in the middle. That’s why our collaboration worked so well.”

George Martin returned once again to produce Wired, but this time around he saw no need to add flourishes like orchestral strings and instead let the band’s performances and arrangements stand on their own. Most of the songs were recorded with musicians playing together live in the studio, recording multiple takes until Beck and Martin were satisfied with the performances and arrangement.

However, Beck repeatedly second-guessed his own work throughout the project. “I was never happy with the solo on ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,’ the Mingus tune,” Beck told Rolling Stone. “I rang George up and said, ‘I’ve got a great idea to modulate that,’ and he said, ‘The album’s been out for two weeks!’ That’s how loose things were back then.”

[Jan Hammer] plays the Moog a lot like a guitar, and his sounds went straight into me. So I started playing like him

Martin produced the entire Wired album with the exception of the song “Blue Wind.” That track was recorded at Hammer’s studio in upstate New York over a period of about a week when Beck traveled there to talk the keyboardist into working on the album. Beck and Hammer performed dueling solos throughout the song, and Hammer provided all of the accompaniment, including the driving bass line and drums.

Wired was decidedly heavier than Blow by Blow, with Max Middleton’s riff-driven homage to Led Zeppelin, “Led Boots,” kicking off the album, and most of the songs having faster tempos and more aggressive arrangements. This time around, the funk elements, while still present, were toned down and less prominent.

Beck’s version of the Charles Mingus composition “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” was a bona fide jazz performance, although his bluesy, slow-tempo approach was more obviously inspired by the acoustic version John McLaughlin recorded in 1971 than the original 1959 Mingus recording. As a result, Wired was more of a true jazz-rock fusion effort than its predecessor, and it inspired the sound and dynamics of numerous jazz-rock albums that came out afterward in the late ’70s.

Although Wired did not enjoy the same level of commercial success as Blow by Blow, reaching a peak position of number 16 on the Billboard album chart, it sold well and earned Platinum certification. More importantly, Wired proved that Blow by Blow’s success was not a fluke, and the one-two punch of those stellar efforts established Beck’s status as one of the world’s greatest guitarists – a standing that endured throughout his career.

His previous work with the Yardbirds was certainly revolutionary, but his foray into jazz-rock fusion delivered performances that were more timeless and lasting, earning him both lifelong fans and well-deserved respect for his tone, touch and taste.