“When I started falling in love with guitar-driven music, I found that all roads led back to him”: Why Jimi Hendrix is still inspiring the latest generation of guitarists – five decades after his death

The stage was dark when Melanie Faye began her solo performance at the closing session of Summit LA18, an invitation-only gathering of ideas and innovators held in downtown Los Angeles in November 2018.

The lights slowly rose as she picked jazzy notes from a surf-green D’Angelico semi-hollow guitar, and by the time she segued into a rendition of Little Wing, they had revealed a stage nearly empty except for Faye.

A fresh face in the guitar pantheon, Faye had only become “internet famous” the previous year when a simple smartphone video shot as she sat on a floor playing a Stratocaster went viral. But her dexterous fretboard skills, and the influence of Jimi Hendrix upon them, were undeniable. She didn’t shy away from acknowledging her hero, either – a poster of him hung on the wall behind her, as if to announce her arrival to his lineage.

Five years later, the now 25-year-old Nashville guitarist’s intoxicating, inventive mashup of the Jimi Hendrix classic with an instrumental variation on pop singer Mariah Carey’s Number 1 hit My All has garnered millions of views on YouTube and inspired a transcription video that has clocked tens of thousands of its own.

That Faye’s reading of Little Wing was based on a version played by Eric Gales – who was hailed as the second coming of Hendrix when he first entered the national scene in the ’90s – reveals the connection generations of artists, and guitarists in particular, have to the music Hendrix created. There can never be another Hendrix, but the cosmic dust he left behind still informs and inspires the galaxy of music being created today.

“If you’re gonna do Hendrix at this point, like 50-something years later, you’d better put some type of unique interpretation on it, an unexpected twist, because we’ve heard it a million times,” Faye says. “It’s not enough to just hold a candle to his cover. You also have to put your own spin on it.”

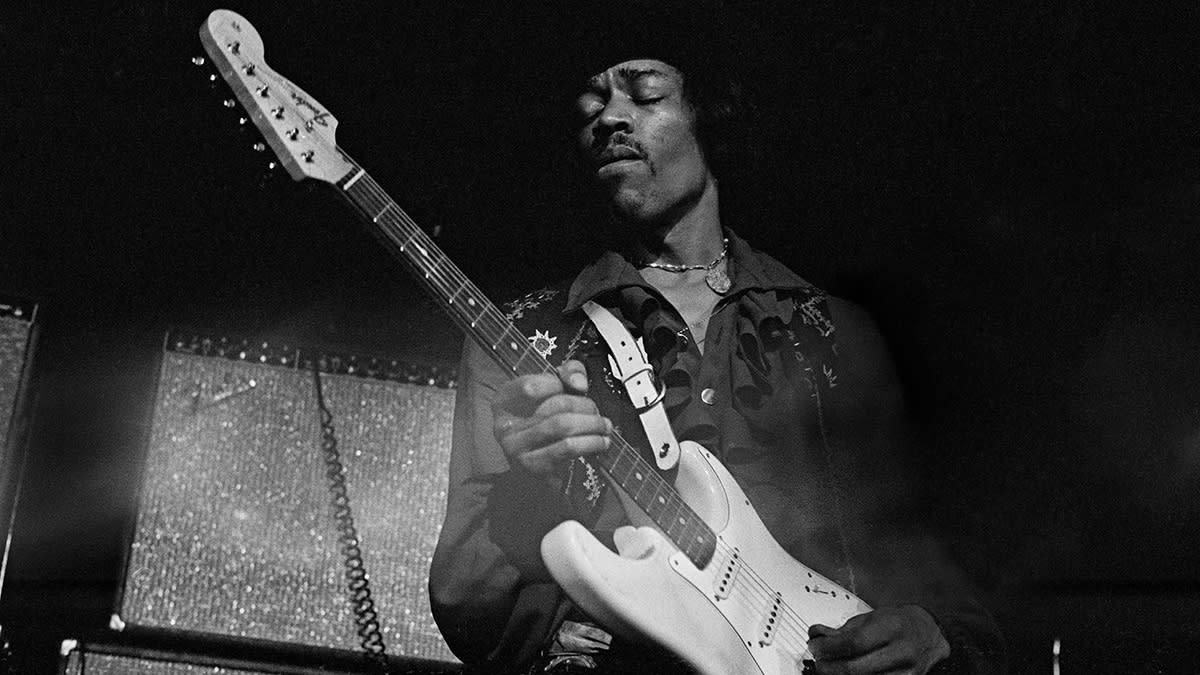

James Marshall Hendrix was born in Seattle, Washington, on November 27, 1942, and died at age 27 in a London flat, half a world away, on September 18, 1970. Of the intervening years, his most prolific were his most visible, riding a wave of fame as the prince of psychedelic rock in the late 1960s.

He broke all the rules of pop music culture with outlandish, ear-splitting performances full of guitar acrobatics, wailing feedback and his casual charm, arriving at a time when American and British musicians weaned on blues and early rock ‘n’ roll were beginning to experiment with the boundaries of pop music.

The year the Jimi Hendrix Experience released their debut album, Are You Experienced – 1967 – also saw the debuts of influential bands like the Doors, Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, the Velvet Underground and Big Brother and the Holding Company; not to mention pivotal works by established artists, including the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow and the Who’s The Who Sell Out.

That June, before American audiences had even heard his record, Hendrix performed an incendiary set at the Monterey Pop Festival in central California, opening with a furious rendition of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor and ending with his slinky take on Wild Thing, climaxed by setting his Stratocaster on fire and smashing it to pieces.

And then there were Hendrix’s own songs, led by his visionary guitar playing and lyricism and rooted in rhythm and blues. The Wind Cries Mary, which showcased his signature double-stops and preference for fretting chord tones on the low E string with his thumb instead of barring across all six strings; the 12-bar blues of Red House; the pentatonic box workout of Manic Depression; and Purple Haze, a monstrous, career-making groove built around an E7#9 chord, which he used often enough for it to become known as the “Hendrix chord”.

While he had to go to England to find fame on his own, his guitar style was cemented playing clubs primarily across the American South, where he helped evolve R&B and soul into funk.

During his years on the chitlin’ circuit – a loose network of clubs and juke joints that catered to Black artists and audiences – through the early and mid ’60s with Little Richard, the Isley Brothers and others, he honed an unshakable sense of rhythm and mastered the pentatonic and blues scales that were the foundation of his playing.

“In my eyes, his rhythm work doesn’t really get talked about a lot,” says Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, who spent his teenage years playing blues festivals and the remaining juke joints around the American South. “It was a big thing for me, and a lot of people don’t know that he played on the chitlin’ circuit and he came from the R&B world. He was definitely steeped in rhythm guitar playing.”

On the 1965 Isley Brothers song Move Over and Let Me Dance, for example, the guitar work is fully formed Hendrix – the lines between rhythm and lead guitar are blurred as he frets rubbery pentatonic lines between chords, which is to say most of the time. He even throws in a variation on a 7#9 chord.

Rhythm and blues is also where neo-soul artist Faye relates most to Hendrix. While she certainly has the chops to pull off Hendrix’s more fiery work, she deliberately tones down her shredder side when working with other artists, opting to lean into the cleaner tones and textures in Hendrix’s playing and his R&B roots.

“R&B is relevant to my generation,” she says, “and if I emphasize that influence, I’ll be able to work with more modern artists.”

Her strategy is definitely working, as she performs and collaborates with pop artists like Mac DeMarco, and with rapper Russ on Fatima from his 2023 album, Santiago. “It’s a very distinct guitar riff, but I also did the bass, and then I wrote the melody for the hook and co-produced the drums. That song is channeling an R&B, hip-hop-adjacent sort of vibe.”

A deeper listen reveals another layer to the song, though, as Faye explains. “I’m hitting the Hendrix chord over and over again, but it’s removed from context. I’m doing it like a jazz embellishment in a contemporary R&B, hip-hop-adjacent modern context, not in a psychedelic rock context, not just because I want it to be relevant to my generation, but also because I wanted to alter the perception of the guitar. I didn’t want people to look at the guitar and think, ‘more cliché rock and blues licks we’ve already heard.’ I wanted to put a fresh, modern R&B spin on it.”

For Seattle rock guitarist Ayron Jones, Hendrix’s chord inversions have inspired songs like Take Your Time from his 2021 album, Child of the State, and Blood in the Water from his 2023 release, Chronicles of the Kid.

“On Take Your Time, I’m using an inverted E6, which is basically taking the bass out of the E6 chord and inverting it to a third and holding down the rest of the chord, so the bass is actually the harmony,” he says. “And then I’m just kind of walking in it, almost like a C# minor – but it’s over a major.”

Brazilian virtuoso Mateus Asato, a shredder who started out worshiping players like Steve Vai, Steve Morse and Joe Satriani, found his way to Hendrix working backward through John Mayer and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

“It was just me playing distorted and trying to be as fast as possible,” he says. “I just wanted to play the scales and try to be clean with my arpeggios, all that stuff. But then I realized maybe that wasn’t my path.”

I don’t even know how to describe what that is. You play a chord, and I mean, we know it’s the pull-off, the hammer-on, the double-stop, whatever. But again, there’s no term – it’s just Jimi

Taking inspiration from Hendrix’s funkier, more soulful side for his work with Silk Sonic, the supergroup created by Bruno Mars and Anderson .Paak, Asato’s playing is heavily indebted to the ’70s funk, soul and R&B that Hendrix inspired.

“When it comes to just the rhythm guitar playing, Bruno was very specific, like, ‘Man, you’ve got to add those little nuances in between chords so it just makes everything prettier,’” Asato says.

“Just the brightness of those little nuances, the technique of Jimi – I don’t even know how to describe what that is. You play a chord, and I mean, we know it’s the pull-off, the hammer-on, the double-stop, whatever. But again, there’s no term – it’s just Jimi.”

While creating a new chord vocabulary with his 7#9 and proclivity for the C major shape are key to Hendrix’s continued influence on new generations of guitarists, his other technical and stylistic innovations are also alive and well.

22-year-old YouTuber Ayla Tesler-Mabé has amassed nearly 200,000 subscribers on the platform by posting videos of her playing songs like Hey Joe, Voodoo Child and May This Be Love. She has parlayed that success into deals with Fender and Ernie Ball Music Man and a collaboration with Willow Smith, and is now releasing her own soulful, guitar-driven pop singles on Spotify.

“When I started falling in love with guitar-driven music, I found that all roads led back to him,” Tesler-Mabé says. “It seemed like he was the root that so many guitar players from his generation – all the way up to my generation – cited as this monumental, game-changing artist. That piqued my interest, and from there, I slowly made my way into his musical universe and began discovering for myself his impact and what he meant.”

On her 2023 single Haven’t Seen Much of U Lately, Tesler-Mabé layers wah-drenched pentatonic runs over its melodic, funk-lite chorus, switching from major to minor and back as the root note changes, reminiscent of the licks Hendrix plays over the second half of One Rainy Wish from Axis: Bold As Love.

“You can really get so much mileage out of pentatonic,” she says. “When you analyze Hendrix’s rhythm playing, pretty much all of it is just [the] major pentatonic scale over major chords and then doing that for minor chords with the minor pentatonic scale. When I realized that, the fluidity opened in my playing.”

Double-stops – or, more generally, a dyad, playing two notes at the same time – are often the grease that enables such fluidity between Hendrix’s chords and notes, and he used them in many different ways. He opened Hey Joe with a dyadic slide, for example, and the hammer-on variation he used throughout his work, but notably on songs like The Wind Cries Mary and Little Wing, might be his most signature move of all.

“Little Wing is the perfect example of a song that was written a while ago but still makes sense today, and you’re still finding out things about it, whether it’s what he was singing about or the guitar playing,” says Philadelphia-based blues guitarist Greg Sover.

“The little embellishments and flourishes count so much, and if you ask me, they influenced a lot of music today, a lot of R&B, neo soul. There’s still a lot of rock music that uses those double stops. And that was probably the biggest inspiration and lesson I’ve taken from the whole situation, from Jimi Hendrix, period.”

Earlier this year, Sover took the stage at the Newtown Theater in Newtown, Pennsylvania, to play a two-hour tribute set of Hendrix tunes where he reached deep into his catalog, playing songs like May This Be Love, Up from the Skies and the slow-burning, 15-minute Voodoo Chile alongside the better-known Voodoo Child (Slight Return) and his other famous songs.

Jimi just took the guitar somewhere else. It made you really think, and it just actually makes you keep on thinking

For his 2023 album, His-Story, Sover collaborated with Band of Gypsys bassist Billy Cox on covers of Manic Depression and Remember, a chirpy deep cut from Are You Experienced that also showcases his double-stop technique.

“Jimi just took the guitar somewhere else. It made you really think, and it just actually makes you keep on thinking,” Sover says. “He inspires you to keep looking a little further, because Jimi Hendrix is already done, so you don’t want to do what he’s done already. You want to leave that to the genius that he is already, but on your instrument itself, it makes you want to search more.”

Asato, who studied Hendrix at Musicians Institute in Los Angeles – in a class actually devoted to Hendrix’s guitar playing – credits Jimi’s double-stops with inspiring him to look beyond the conventional separation of chords and licks and continuing exploring the instrument.

“[In the class,] we would grab a chord progression and then add those nuances in between the chords,” Asato says. “That class specifically was game-changing [in terms of] opening my horizons. The double-stops pretty much changed me; it was a mind-blowing thing. I was like, ‘Okay, I need to drink that as much as I can.’

“He was just moving by the flow of his creativity and the freedom of what was in his mind, and that was the most revolutionary part of him. It’s so experimental. He plays blues, but it’s not blues. It’s just so freeform, and that’s what I love.”

Texas blues guitarist Ally Venable, who has five solo albums to her credit – including her 2023 set, Real Gone, which includes collaborations with Buddy Guy and Joe Bonamassa – finds inspiration in Hendrix’s songwriting legacy. Tackling Castles Made of Sand for the Experience Hendrix 80th anniversary concert, which took place last year in Austin, renewed her fascination with his approach.

“It opened up a new perspective [for me] on how he approached his songwriting,” Venable says. “There’s, like, three different stories in one song, and each verse is its own story. He puts a picture in your head, and it’s this whole creative experience. And the way Hendrix sings is not the normal way people phrase things; his phrasing is so different.”

For Venable, Hendrix’s overall creativity as a musician makes him “probably the most influential guitar player of all,” for all the stylistic quirks no other players were using at the time.

“One of the main things Hendrix is known for in his guitar playing are his chord structures and the way he structures his songs, these really intricate chord progressions nobody else was doing, and still a lot of people don’t do now because it’s so difficult,” she says.

“Also, the things he would try in the studio. He would overlay guitar parts on top of guitar parts – and the backwards playing… Nobody really did that either.”

He was able to make his guitar sound like so much more than just a guitar

But the techniques Hendrix championed that made the biggest impression on successive generations of players might be those from his August 1969 performance of The Star Spangled Banner at the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in Bethel, New York.

Simultaneously patriotic and subversive, Hendrix reimagined the National Anthem as a fuzz-drenched, gnashing display of trills, bends and tremolo divebombs that sustained into washes of feedback and soared into the early morning sky. There had been guitar heroes before, sure – who could forget the “Clapton is God” graffiti in 1966? – but those three minutes and 43 seconds of revolutionary sound cast Hendrix among the immortals.

“He was able to make his guitar sound like so much more than just a guitar,” Tesler-Mabé says. “He found ways to emulate human voices and screaming and bombs and warfare.”

As cosmic as Hendrix could be on extended journeys like 1983 (A Merman I Should Turn to Be), and as tender as he was on May This Be Love and Little Wing, Hendrix also helped create heavy rock music before “heavy” was anything more than bad ’60s slang for “serious.”

He wasn’t alone in this respect; on their landmark 1964 hit You Really Got Me, the Kinks upped the ante for rock ’n’ roll with perhaps the first hard-rock riff. And in 1968, Helter Skelter by the Beatles and Born to Be Wild by Steppenwolf joined the party.

But on the first song of the U.S. version of Are You Experienced, Hendrix preceded both with Purple Haze, a proto-heavy metal song in every respect. While drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding pound away in lockstep rhythm, Hendrix slices through with the song’s signature descending riff, then shout-sings atop the main E7#9 - G - A verse progression.

Structurally, there is no chorus but a solo followed by a return to the opening motif, then a siren-esque, ringing double-stop with a whole-step bend until the song fades out.

“There’s something so brave about those two [opening octave] notes,” Sover says about the song that changed his life and put him on a path to pursue music. “What captured me the most would probably be the tone. It was strong, and it came in with bravado. It was like, ‘What is this?’”

“There’s this amazing swagger, and you start to notice there are a lot of phrases where he’s off the beat, but he always comes back in a way that’s so interesting and expressive,” Tesler-Mabé says. “Like on Purple Haze, there’s this one line in the intro that has this incredible behind-the-beat swagger to it. I never heard a player with so much feel and freedom in his rhythm playing.”

I never heard a player with so much feel and freedom in his rhythm playing

While Van Halen successfully updated You Really Got Me on the band’s eponymous 1978 debut album, no such move has been made on Purple Haze. Frank Zappa and the Cure have both reimagined the song in their own ways, and admirably enough, but neither improved on the original.

The same might be said for Manic Depression, although plenty have tried (including Jeff Beck & Seal in 1993). Aggressive bands like Carnivore and Nomeansno covered it, and it’s also featured on Sover’s His-Story.

Sandwiched between Temptation, with its Red House shuffle, and the heartland rock of One Way Train, Sover’s faithful take puts the chop he learned from Hendrix on full display.

Progressive metallers Moon Tooth, propelled by the shredding of Nick Lee, recorded a particularly ballsy version in 2017 that solidified their reputation while retaining much of what Hendrix laid down.

“I wanted it to still pay tribute to him and the band, but I wanted it to sound like Moon Tooth,” Lee says.

“One thing I wasn’t gonna try to do is the solo exactly note for note, because my guess is he probably just plugged in and fucking ripped his solo. It wasn’t like he sat with manuscript paper and wrote it all out. So I just plugged in and improvised a bunch of solos and picked my favorite one. It feels true to the solo. It pays tribute to the feel of it more than the actual music theory part.

“It’s almost upsetting when someone that’s into heavy music hasn’t gotten to the point where they appreciate Hendrix and those records, just because of how heavy it is and how it runs a gamut of different types of music, but still sounds like him. It’s all coming from his hands.”

Ayron Jones, whose 2020 single Take Me Away drew a sonic connection between Hendrix and Tom Morello, grew up in the same central Seattle neighborhood as his hero and met people who were part of his early life, including one of his babysitters, grounding the legend in real and familiar places and faces.

Growing up in the ’90s, Jones attributed the source of his hometown’s grunge scene with its original rock star – an association few made at the time, but which makes perfect sense in retrospect.

“The Seattle sound really started with Jimi Hendrix,” Jones says. “Look at a lot of the stuff he did, and look at the guitar players from the grunge era. He was the prototype when it comes to all the music that we love, all these things we think of as innovative sounds.”

The most obvious example might be Mike McCready, whose Hendrix-via-SRV playing on popular Pearl Jam B-side Yellow Ledbetter and devotion to wah-wah licks played on a Stratocaster gave him away. And recall Kim Thayil’s use of feedback noise in Soundgarden – and even Jerry Cantrell, who has cited Hendrix as a primary influence.

And let’s not forget the hard funk-rock hybrid Hendrix pioneered on Axis: Bold As Love cut Little Miss Lover or the all-timer Fire, from his debut. He returned to that feel on the songs immortalized on the live record Band of Gypsys in 1970 – Power to Love has the kind of riff Morello would later write in Rage Against the Machine, and Machine Gun features Jimi’s use of percussive, pitchless “chuck-a” fret-hand-muted strums that Morello would employ on songs like Bombtrack.

Progressive neo-soul and funk artist Marcus Machado, who discovered Hendrix early enough to play The Wind Cries Mary for his kindergarten graduation, worked his way backward through the Experience catalog from Electric Ladyland before landing hard on Band of Gypsys, which he credits as the first true funk rock album.

The way he sang through the guitar and made the guitar into another human voice was the thing that stood out, like he was the lead singer – but the guitar was also the lead singer

“Electric Ladyland was one thing, but Band of Gypsys was a whole other spectrum,” he says. “A lot of people don’t know, but that’s where George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic got their stuff. Band of Gypsys was the first funk rock band; after Jimi passed, that’s when Funkadelic and Eddie Hazel and all that came about.”

It was the funky Fire that stood out most to TikTok star-turned-recording artist Towa Bird, who cranked Are You Experienced on her headphones while riding the school bus in middle school.

“The way he sang through the guitar and made the guitar into another human voice was the thing that stood out, like he was the lead singer – but the guitar was also the lead singer,” she says.

“I thought that was so rare and unique. The melodies, riffs and licks he chose felt so human, and he made the guitar cry. It has the same spirit and the same soul that a human voice has.

“I think the way he uses really simple forms and phrases over and over again, it’s like ear candy and ear-wormy. He uses simple pentatonic boxes and works around that and says so much with so little. Especially his call-and-response technique where he’ll sing and then respond with the guitar.”

To listen to Hendrix is to submit to his trip, and each generation of guitar players continues to embark on a lifelong journey led by the otherworldly adventurer of Electric Ladyland, the visceral dreamer of Axis: Bold As Love, and the hitmaking revolutionary of Are You Experienced.

While it’s impossible to understate Hendrix’s influence on guitar and pop culture, his legacy has always rested in the hands of his fans.

“I know a lot of the young rockers and young blues guitar players from my generation,” Ingram says, “and we all have a little bit of Hendrix in us, like Taz [Brandon Niederauer] and Quinn Sullivan. I don’t care how anyone tries to put it, Hendrix is somewhere in everybody’s playing.”

Because of that undeniable lineage, the innovations and emotional range Hendrix brought to the instrument and music itself continue to find audiences.

The true genius is when you’re older, still listening to it and finding new things or figuring out what he was really saying

“I’m always finding different ways to be an emotional guitar player, and I think that that is really how Jimi carries on,” Jones says. “Finding ways to move crowds and try to connect in this emotional way, because for Jimi the guitar became a spiritual device as much as it is an instrument. I’m always trying to connect with people by using my instrument to connect to the spirit.”

“The true genius is when you’re older, still listening to it and finding new things or figuring out what he was really saying,” Sover concludes. “What inspires me more than anything is this futuristic thing in his music that keeps the music alive today, where nothing is outdated in what he’s singing about.”