Sean Penn’s Crusade: Why He’s Risking It All for Ukraine, Furious at Will Smith and Ready to Call Bulls— on Studios’ AI Proposals

Summer light fades to gold in Malibu. Surfers carve tasty waves just down the road. A beautiful woman wanders toward the pool house. She crosses paths with a sweet dog heading the opposite way looking for an ear rub.

Diet Cokes are poured at Sean Penn’s house. Small talk is made about how the coffee table in his living room looks like a junk drawer just exploded on it. There are sunglasses, prescription bottles and a device that shoots salt at mosquitoes. Nearby are photos of famous people, all smoking. They are opposite a poster for “A Man Called Adam,” a Sammy Davis Jr. film directed by Leo Penn, Sean’s father.

More from Variety

Sean Penn on Meeting 'Reptilian' Vladimir Putin and Trump's 'Angry Used Car Salesman' Mug Shot

'Daddio' Review: Sean Penn Takes Dakota Johnson for a Ride in Bold, Conversation-Igniting Debut

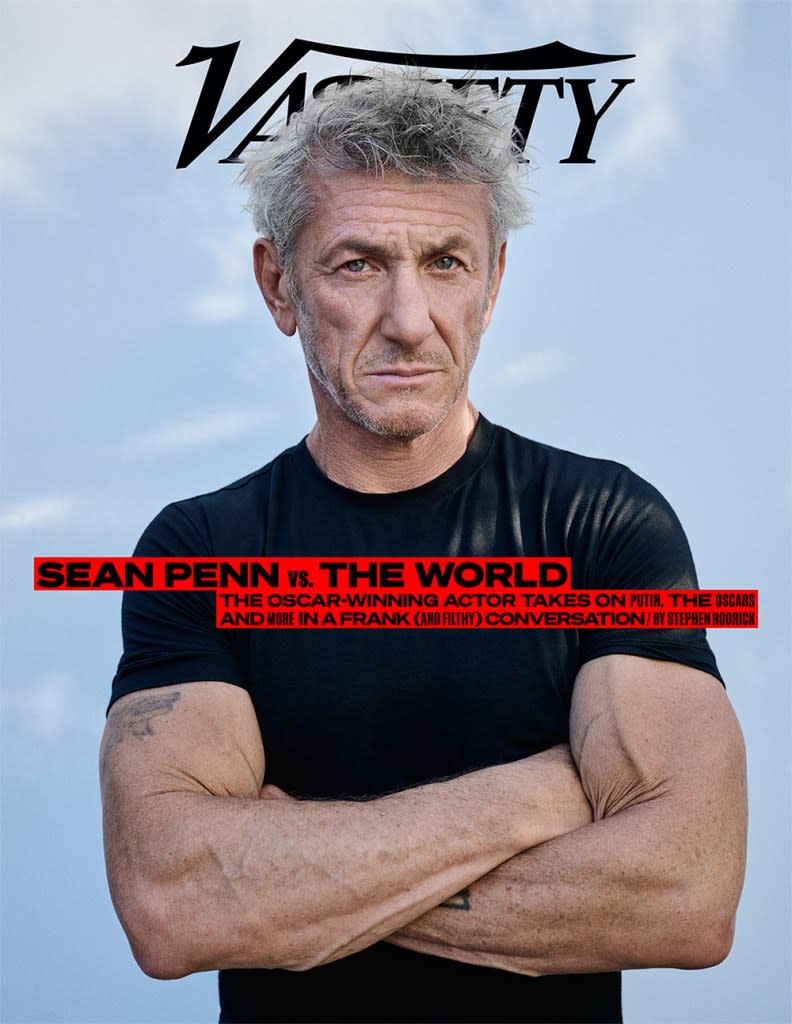

Another wall holds a frame containing a Ukraine Order of Merit medal. Penn is 63 and dressed in a simple T-shirt and blue jeans. His hair is now a shock of white. He speaks of the United Nations, surface-to-air missiles and F-16s. Mostly, Penn talks about his friend Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the subject of his documentary “Superpower,” which premieres on Sept. 18. He sounds like an affable, between-gigs diplomat enjoying some downtime before a semester at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

The era of good feeling passes. Penn gets angry. OK, fucking furious. He ignites over the Academy’s refusal to let Zelenskyy speak at the Oscars in 2022, shortly after Ukraine was invaded by Russia.

“The Oscars producer thought, ‘Oh, he’s not light-hearted enough.’ Well, guess what you got instead? Will Smith!”

After winning his second Oscar for “Milk” in 2009, Penn remarked, “I want it to be very clear that I do know how hard I make it to appreciate me.” This is a true statement. His face is now crimson; a vein in his neck tightens like a rope pulled taut. “I don’t know Will Smith. I met him once,” Penn says. “He seemed very nice when I met him. He was so fucking good in ‘King Richard.’” He lights another in an unchained melody of American Spirit cigarettes. “So why the fuck did you just spit on yourself and everybody else with this stupid fucking thing? Why did I go to fucking jail for what you just did? And you’re still sitting there? Why are you guys standing and applauding his worst moment as a person?”

Someone pops a head in to make sure everything is OK. Penn waves them away. He is not done.

“This fucking bullshit wouldn’t have happened with Zelenskyy. Will Smith would never have left that chair to be part of stupid violence. It never would have happened.”

Penn tells me he became convinced his only choice was to destroy his Oscars. “I thought, well, fuck, you know? I’ll give them to Ukraine. They can be melted down to bullets they can shoot at the Russians.”

I get it. Your eyes are rolling clear out of their sockets as Sean Penn publicly loses his temper for the fifth consecutive decade. Fair point. Still, as fellow hot-head John Lydon once sang, anger is an energy, and 2020s Penn anger differs from 1980s Penn anger. It is now productively channeled compared with his youth, when he was a box office idol with a predilection for Madonna and fistfights. Penn spent 33 days in jail in 1987 for punching a guy, as referenced in his Smith cri de coeur.

I was recently reminded of those days when I spied Penn sneering back at me from a photo at The Broad Museum’s Keith Haring exhibit. (Haring was painting in the New York subway in the 1980s while Penn glared from a desiccated “Bad Boys” poster.) That guy is no more in both looks — he now resembles a more handsome Eli Wallach — and deeds. He has replaced the brawler with a humanitarian.

Note that I didn’t put “humanitarian” in air quotes. These are facts. Penn bought his own boat and pulled refugees to safety during Hurricane Katrina. In 2010, he built the highest-functioning refugee camp in Haiti after a devastating earthquake and stayed in-country for months at a time. Lives were saved.

Running on a semi-parallel path has been Penn’s political work. It first surfaced in 2002 when he flew to Baghdad and called bullshit on George Bush’s claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. He correctly predicted the terrible cost of American boys going to fight ghosts in the desert, earning him many foes in the freedom fries caucus.

Back in Malibu, Penn says he would have responded to 9/11 differently if he had been president. His proposal would not have been approved by Amnesty International. “I’d have let White House counsel know that they are on vacation,” Penn tells me. “I’m not consulting with them. If I have to go to prison, I’ll go, but I’m going to kill them. I’m killing everyone that did this. But only them. And we know where the fuck they are.”

Aggressive pop-offs are a Penn staple and not limited to global events. I ask him his thoughts on the Hollywood strikes. He is particularly livid over the studios’ purported lust for the likenesses and voices of SAG actors for future AI use. He has an idea that he is convinced will break the logjam. It starts with Penn and a camera crew being in a room with studio heads. Penn will then offer trade: “So you want my scans and voice data and all that. OK, here’s what I think is fair: I want your daughter’s, because I want to create a virtual replica of her and invite my friends over to do whatever we want in a virtual party right now. Would you please look at the camera and tell me you think that’s cool?”

Penn pauses long enough for me to check if he is serious. That is an affirmative.

“It’s not about business,” he says. “It’s an indecent proposal. That they would do that and not be taken to task for it is insulting. This is a real exposé on morality — a lack of morality.”

These kinds of statements, no matter their moral righteousness, make Penn an easy target for the smirker set, who dismiss his Zelig-like appearances at the crossroads of conflict — Benghazi! Hollywood! Damascus! J6 hearings! — as epic grandstanding. (Matt Stone and Trey Parker’s “Team America” movie lampooned his galaxy brain statements, to which Penn responded with a letter that he signed off with “Fuck you.”) Some of Penn’s international drop-ins have lacked, let us say, a certain moral cohesion. There was his romanticizing of Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez, who some saw as a Third World hero, but many others saw as a petrodollar-fueled demagogue. (It should be noted that Penn did score pallets of morphine from Chávez that brought relief to thousands of Haitians after the 2010 earthquake.)

Sometimes it’s not clear what role Penn is playing as he appears live from this year’s hot spot: Journalist? Activist? Global gadfly? Penn says he’s not a journalist — he wryly offers in “Superpower” that he’s no Walter Cronkite — but merely a concerned citizen who knows his celebrity status can provide him an all-access lanyard to international actors.

One of Penn’s magic passes took him on a 2015 clandestine trip to Mexico for a meeting with fugitive drug kingpin/murderer El Chapo for Rolling Stone. He says he went to better his understanding of international drug trafficking. Alas, that was not the world’s takeaway. Depending on whom you believe, Penn’s visit and the subsequent million-word story (only a slight exaggeration) either led the federales to El Chapo, slowed their efforts or almost resulted in Penn’s death when a lethal raid was only postponed because of bad weather.

I was working at Rolling Stone at the time, and much of the staff wondered why the guy from “Carlito’s Way” was interviewing a narco terrorist. The fact was that only Penn could kick down the El Chapo door — not me or any other reporter. (I would have knocked softly and then run away, hoping no one was home.) But to what end?

Penn admitted that the El Chapo story didn’t advance the drug war conversation. Still, he wasn’t deterred from the sporadic international rumspringa. His kids were grown, and he was long divorced from actress Robin Wright. Acting was losing its appeal, but the need to make dramatic appearances remained.

Around this time, Penn became friends with Billy Smith, a Gulf War veteran and character actor with a similar passion for global chaos. They started to raise money for an Arab Spring documentary. The project took a left turn into a proposed project on Syrian president Bashar Assad, who was clinging to power while a bloody civil war devoured his country.

“After the Arab Spring, all the pundits were saying, ‘He’s gone in 30 days — it’s over,”’ says Penn. “And now it’s five years later. How’d that happen? Aleppo is on fire. What’s going on?”

Most humans would have been satisfied that Assad was still in power because of Russian military backing and an enthusiasm for murdering his own people. Instead, in 2016, Penn made his way to Damascus, where he received an audience with Assad. The president then drove the actor from his office to the family home. “We drove through the middle of Damascus in the middle of a war with him in the driver’s seat,” says Penn with naive wonderment. “People were coming up and saying, ‘Hey, Mr. President!’ There was no sign of security.”

Penn eventually realized that he was in a “Truman Show” version of Syria, with the streets likely cleared of residents. Assad’s home was, according to Penn, a normal place. “The house was extremely accessible,” he remembers. “Very cordial, the family very Western; the kids listening to Kanye West.”

He claims that Assad offered him “carte blanche” access and then slowly took it away, and that is why he punted on the documentary idea. Smith, his partner, had a more real-world concern. “We soured on it,” Smith says, “because it really was like, ‘What is this? What are the optics other than just a really bad guy trying to hold on to power?’”

Penn busied himself with more morally substantial work. In 2019, he converted his Haitian relief organization into the Community Organized Relief Effort, a global disaster relief group. He begged and wheedled the well-heeled in Hollywood for donations, often resulting in angry frustration. Meanwhile, his film career had ground to a halt except for a voiceover in “Angry Birds” and a film with angry man Mel Gibson — 2019’s ill-fated “The Professor and the Madman.” (Recently, Penn has begun to resurface, first with a small role in “Licorice Pizza” and now with a well-received turn in this year’s “Daddio.”) Penn was asked about acting in 2018, and he said, “I’m not in love with that anymore.” That year he published a satirical novel called “Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff ” that was mildly received.

In 2019, Smith and Penn made another stab at a documentary with a proposed project on the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. That seemed promising — Penn traveled to Istanbul, where he gave the middle finger to security cameras outside the Saudi consulate — until they learned that Oscar-winning doc director Bryan Fogel was far down the road on what eventually became the critically acclaimed “The Dissident.” That’s when Smith asked him if he had been following the story of Zelenskyy, an actor who played a president and then became the president of Ukraine. Smith knew a guy working in Zelenskyy’s office.

Penn was intrigued. Everyone agreed this was a doable endeavor; they could get in and out without the ominous stakes of an Assad or a Khashoggi doc. They could talk to the hapless Zelenskyy about the “perfect call” that Donald Trump had placed to him looking for dirt on Joe Biden. Vice Media got on board with financing. It was going to be quirky and whimsical.

“I thought I reached a point in my career where I could do a lighthearted piece,” remembers Penn.

That turned out to be precisely wrong.

“It was like Andrew Jarecki beginning to shoot a doc on clowns,” says Danny Gabai, head of Vice studios and a producer on “Superpower.” “And then it morphs into ‘Capturing the Friedmans.’”

The footage is remarkable. It is Feb. 24, 2022, and Russian troops have invaded Ukraine. Tanks cross the border, missiles slam into Kyiv and paratroopers are landing at the airport. Millions of refugees begin streaming westward.

President Zelenskyy’s country is on the precipice of annexation. Pundits suggest he could be dead or deposed in the next 24 hours. The United States offers to evacuate him and his family. He refuses and tells them to send weapons. Situated in a bunker deep under the Presidential Office building, Zelenskyy meets with his generals and makes heartbreaking decisions: where to commit troops and where to cede territory to Putin’s army. He eventually steps out of the command center for meeting.

It is with Sean Penn.

“It blew my mind he kept the meeting,” recalls Penn. “There were Chechen kill squads in the streets already.” Penn speaks of Zelenskyy’s poise that day in he present tense. “His brain is fully oxygenated. His eyes are clear and he’s warm. I knew I’m either going to feel nothing or I’m going to let myself love him.”

It was love. Remarkably, Zelenskyy and Penn had met in person for the first time just the day before. COVID had delayed the project for two years. Penn first visited Ukraine in the fall of 2021, and the country’s optimism for their new leader had faded to gray. The former comic had earned 73% of the vote in the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election, and now, two years later, there was grumbling that Zelenskyy was in the pocket of an oligarch, exactly what he had run against in a country that has long teetered between democracy and kleptocracy.

Penn and his crew captured other Ukrainians doubting that Zelenskyy had the balls — their expression — to stand up to Vladimir Putin, who had already taken Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions like a rat chewing through drywall.

“We couldn’t find anybody who thought, ‘This is the person we would vote for again,’” remembers Penn. “And that included those who had voted for him before.”

According to Penn, any thought of meeting with Zelenskyy on the 2021 trip was scuttled by a lockdown of his government after a purported intelligence leak to the Wagner Group, mercenaries allied with Russia.

Penn returned to Malibu. In early 2022, Putin massed 100,000 troops on Ukraine’s border. The actor talked with experts who were split on whether this was saber-rattling or a real threat. Meanwhile, Smith and Vice grew itchy. They all wanted Penn to head back to Ukraine.

“We’re in February, and Vice is like, ‘You guys got to get over there,’” says Penn. “And I’m like, ‘I promised to fix these shelves.’” This wouldn’t make sense if I had not noticed Penn’s very active woodshop on my way in. “I just always thought, ‘You gotta go. You can’t say no. You gotta go,’” says Penn. “But when you have an NGO and you’re doing movies and things with two kids, you never are just here,” tapping his own chair for emphasis. For Penn, Malibu isn’t some kind of Shangri-la; it’s where he grew up. It’s home. “It was time to live for me, and I wanted to do the shelves.”

Apparently, the shelves got finished because Penn and a crew headed back to Ukraine in February 2022 and found a nation on the brink of war. They interviewed experts, journalists and ex-soldiers, and “Superpower” gives you a nauseous feeling of the walls closing in. Then National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, a friend of Penn’s, urged him to leave the country lest he become a celebrated hostage for Putin. Penn insisted on sticking around. There was a promise that Zelenskyy would meet with him, and he knew it might be his one and only opportunity.

A get-acquainted meeting was set for Feb. 23, what turned out to be the eve of the invasion. Penn had one stipulation: The initial encounter would not be filmed. “I wanted him to be able to decide if we could build trust, and you can’t do that with cameras rolling.”

They met in Zelenskyy’s office, the prime minister in a suit. Penn and Zelenskyy had common ground: Both were actors; both were warily viewed by large segments of their countrymen. Zelenskyy was originally a stand-up comic, known for playing the piano with his penis in a comedy skit. Penn was originally known as Spicoli, the surfer dude who brought “gnarly” into the common vernacular. Circumstances had changed.

Some viewed Zelenskyy’s affable breeziness — namely the very fact he was spending time with Penn — as the attitude of a clueless man. Penn saw it differently. He saw Zelenskyy’s calm as someone expressing the “last bullet of optimism” that his country could continue without carnage.

It didn’t happen. The next morning, Russia struck and Zelenskyy was spirited to his bunker. O’Brien again urged Penn to leave.

“My biggest concern at the time was that Sean was with Zelenskyy,” O’Brien says, “and I assumed the Russians were going to try a decapitation strike and take Zelenskyy out. I didn’t want Sean in the bunker when it got hit by a missile.”

Penn ignored the advice and descended to meet Zelenskyy, who had lost the suit and moved into his now famous military fatigues. In these segments of the film, Zelenskyy looks exhausted but steadfast. He insists he will never abandon his country.

Afterward, Penn and his crew made their way back to their hotel through a blacked-out city. Penn still gets emotional as he recalls the meeting.

“I got this feeling I might never get to see that guy again,” says Penn, his voice cracking. Of course, Penn did see Zelenskyy again, another half-dozen times over the next year. They grew close, and Penn is not bashful about his admiration.

“I saw a very big change in him from one day to the next,” says Penn. “At that moment, he was the significant target. But he wasn’t going anywhere. That day, he found out that he was born for this.”

In retrospect, Zelenskyy’s meeting with Penn was not quite as preposterous as it seemed at the time. The president knew Ukraine could not survive without Western support and arms, so he proceeded to launch a media rollout that would be the envy of any Hollywood publicist. He spoke via satellite to Congress; he doled out exclusives — anything that would keep the West interested and on his side. It was a media blitz worthy of a former actor whose chief of staff used to be his entertainment lawyer.

“I think he thought, ‘Sean Penn will be a grain in the sand of this beach for us,’” says Penn. “That was part of fighting the war for him. That is as important as any soldiering. He’s got to do it.”

Penn and his crew fled to Poland the day after the meeting, maneuvering around Russian troops and blown-up bridges. He returned to the United States and started beating the bushes for Ukraine. He even went on Fox News’ “Hannity,” a show that had mocked him in the past. Penn was clad in an Army surplus jacket, and the two foes — Penn and Sean Hannity — found common ground celebrating Ukraine’s resolve.

“When you step into a country of incredible unity, you realize what we’ve all been missing,” he said to Hannity. It was a common Penn sentiment that echoed his thoughts on Haiti: “There is a strength of character in the people who have, by and large, never experienced comfort. That’s exactly the character that our Main Street culture lacks and needs in the United States.” Both are noble statements that oddly suggest what America needs for unity is an apocalyptic event.

Penn’s demand that the United States arm Ukraine dismissed any lingering thought that he had ever been some kind of Cali peacenik. He went to Washington and lobbied for F-16 fighter jets for Ukraine. The United States and NATO initially balked, so Penn pursued the issue through nontraditional avenues.

“Sean was talking to billionaires to say, ‘Why don’t you buy a fleet of F-16s?’” recalls Smith. “‘Can we purchase 12? Can we get a mothballed aircraft carrier, so we don’t have to put them on NATO ground?’”

Penn had no time for hand-wringing about providing weapons that would be used against Russia, an unstable nuclear power. He responds with sarcasm when he mentions, unprovoked, a critic who said the last thing the world needed was Sean Penn calling for a military escalation.

“Don’t encourage these Ukrainians or support them to win this thing we all say we stand for because you might create problems for us that are nuclear,” says Penn with exasperation, paraphrasing the critic. He ushers in his second unfortunate analogy of our near three-hour conversation. “It’s saying, ‘OK, I’ll be your bitch. You want my daughter as your sex slave?’”

Fortunately, “Superpower” avoids the sub-“Deadwood” rhetoric and concentrates on Zelenskyy and his fellow Ukrainians fighting for their lives, even if there’s a bit too much Sean Penn doing Sean Penn things in a war zone. The documentary will give a push to Zelenskyy’s cause at a moment when support for the United States continuing military aid to Ukraine has dipped below 50%. Paramount+ is distributing the documentary with Susan Zirinsky, the former head of CBS News and now president of See It Now Studios overseeing the launch. She promises an epic push. Penn will appear on all the CBS news shows, including “Face the Nation.” Two billboards will reign over Times Square. “That’s the advantage of working with us,” says Zirinsky. “We’re a rolling thunder of promotion.”

It will be interesting to see if any CBS news correspondents push back on Penn’s version of the war. He has never pretended to be objective, and the film is a persuasive advertorial for Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian cause. O’Brien says there is nothing wrong with that. “‘Propaganda’ gets called a bad word too much,” says O’Brien before rhapsodizing about Walt Disney’s agitprop films in World War II. “We still live in a world where sometimes there are good guys and bad guys, and the good guys have a story to tell. Sean’s telling it.”

“Superpower” features a handsome Ukrainian Air Force pilot named Andriy Pilshchikov with the call sign “Juice.” Pilshchikov resembles a “Top Gun” extra, so it’s no wonder he ended up in Washington, D.C., lobbying the United States for F-16s. In the documentary, Pilshchikov talks about the Ghost of Kyiv, a mysterious Ukrainian pilot who seemed to be everywhere in the early days of the war, protecting his homeland’s skies. Juice cops to the Ghost being a myth but argues that all who fly to protect Ukraine are their own ghosts of Kyiv.

Juice was killed in a training accident on Aug. 25. He became one of more than 100,000 Ukranians lost to the war. “Andriy was a consummate war fighter who radiated the dream of peace and freedom,” says Penn about his friend. “He was a beautiful, beautiful man.”

Penn feels the loss but fights vehemently against the dovish view that the United States is somehow equally culpable in the violence for providing weapons to Ukraine. “Loss and destruction are the legacy of Putin,” he says. “There’s no version of the world where this invasion will ever make sense.”

At the end of our conversation, Penn mentions that he decided not to melt down his Oscars for Ukrainian bullets. Instead, he gave one to Zelenskyy. “I told him to keep it and bring it to Malibu after all this is over and his country is safe,” says Penn with a hopeful smile.

I thank Penn for his time and mention I’m heading directly to Zuma Beach for a sunset swim. He offers an alternative and gets a fob for entrance into a beach only accessible to Penn and his neighbors.

There’s a gate topped with barbed wire to keep the riffraff out, and then long and winding stairs down to the sea. It’s magic hour, and there are teenage surfers who are giving each other shit and using the words “awesome” and “gnarly.” I venture down, and the water is not as it appears — it’s uneven and rocky under the surface. I baby-step my way out and notice another danger: If you’re surfing here and cut to the left, you’re going to ride right into a cliff.

A dog looks out from the rocks above me and barks with purpose. Then someone says the dog is a real sweetheart, once you get to know it.

Best of Variety

'House of the Dragon': Every Character and What You Need to Know About the 'Game of Thrones' Prequel

25 Groundbreaking Female Directors: From Alice Guy to Chloé Zhao

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.