Roger Corman interview: ‘Horror today just gets gorier and gorier’

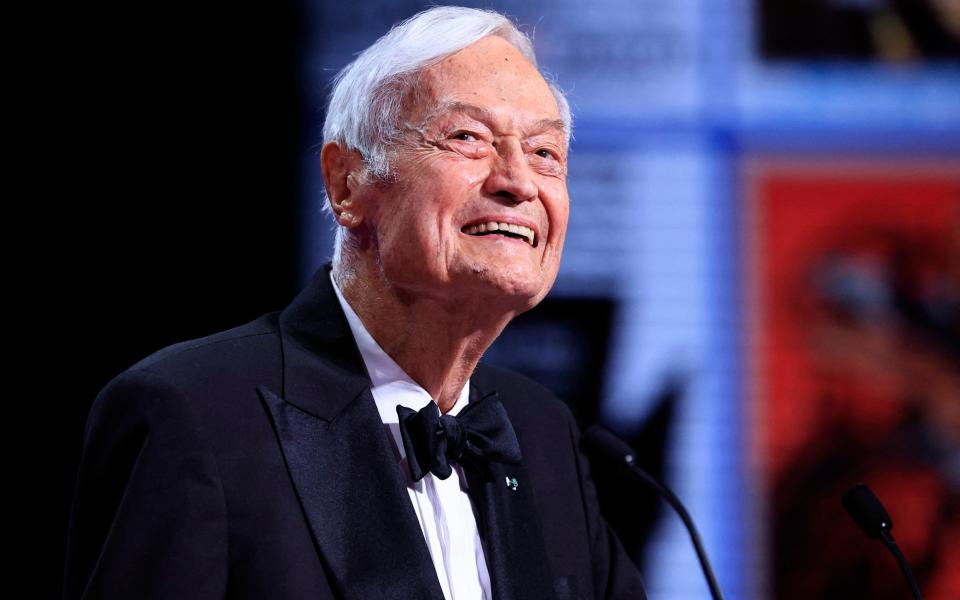

Roger Corman, director and producer of hundreds of films including 1960’s Little Shop of Horrors, has died aged 98. In this 2013 interview from The Telegraph’s archives, he spoke candidly about his long career, and the state of contemporary horror cinema.

At 87 years old, Roger Corman is a twinkly gent. He walks with a pronounced stoop, and speaks in careful, precise sentences, making considerable effort not to waste a word. It’s hard to believe the career this benign legend has had, not to mention the careers he’s given others – he gave Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Fonda, Jonathan Demme, Pam Grier, Ron Howard, James Cameron and Jack Nicholson their first breaks.

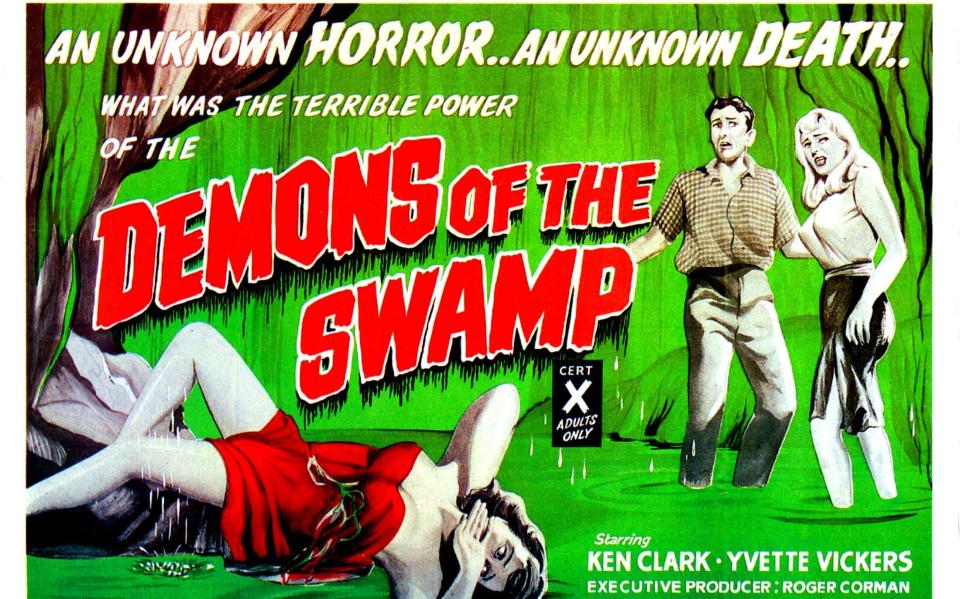

Along the way, Corman has written a handful of films, directed 56, had a couple of dozen, mostly uncredited acting cameos, and produced, in some capacity, about 400 movies. The titles include some of the most wonderfully lurid in film history – take 1957’s Attack of the Crab Monsters, or The Wasp Woman (1959), or Ilsa the Tigress of Siberia (1977). Astonishingly, he’s still working – something called Dance with a Vampyre would appear to be in production now – though he hasn’t directed a film himself since 1990’s Frankenstein Unbound.

Corman is in London for a stage interview as part of the BFI’s mammoth Gothic season. He’s using the invitation as an excuse for a European mini-break with his wife Julie, a fellow producer whom he married in 1970. And he seems happy to share any and every anecdote he’s collected on the job.

There are so many Corman stories out there that I first wonder if there are any he’d like to debunk. Did he really tell Coppola not to go to the Philippines to shoot Apocalypse Now?

“Having made films there myself, I said, ‘Francis, don’t go! You’re going into the rainy season.’ He said, ‘Oh, it’ll be a rainy picture.’ But it’s not rain as we know it. It starts in May and continues through to October. His set was wiped out. And the insurance paid out on the basis of a monsoon. But there was no monsoon! It was just normal July weather. He went back in good weather and made the film.”

It’s pretty incredible how many of these Oscar-winning American film careers were hatched under the auspices of American International Pictures (AIP), for which Corman was the in-house director/producer, and New World Pictures, a production-distribution company which he founded personally in 1970 with his brother Gene. He produced Coppola’s Dementia 13 (1963), Bogdanovich’s Targets (1968), Scorsese’s Boxcar Bertha (1972) and Demme’s Caged Heat (1974). All served an apprenticeship under Corman for a film or two, then moved on to their celebrated studio heyday. But he remained in good touch with the lot.

Jack Nicholson was a different case. They met in a Hollywood acting class where Corman was scouting for talent. The budding impresario gave Nicholson the lead as a juvenile delinquent in his screen debut, The Cry Baby Killer (1958), and for the next 10 years, used him in a whole string of drive-in exploitation cheapies, playing rebel bikers and the endlessly terrorised heroes of Gothic chillers. Nicholson’s career obstinately refused to take off until his mainstream breakthrough with Easy Rider (1969), at which point it was time for these two to go their separate ways. But it was much more than just a professional bond – in the 2011 documentary Corman’s World, Nicholson spontaneously tears up when talking about the importance of Corman in his life.

The movies Corman directed himself started out as the definition of shoestring, but he sometimes feels their rough-and-ready qualities get exaggerated. “The myth that when I was directing that I was always printing the first take. I would generally go two, three, four takes. First take is generally not exactly what you’re looking for.”

There are a couple of directors who do famously like to use first takes – Clint Eastwood, Jean-Luc Godard. And then there are the Stanley Kubricks, obsessively calling for another and yet another, at the opposite end of the spectrum.

“With me, Jack Nicholson would generally go second, third take,” remembers Corman. “Kubrick on The Shining went over 100 takes on one scene. I can’t remember exactly but it was 120, 130 takes or something. And Jack is a good guy, and stood there doing his lines 120, 130 times. And he told me he went up to Kubrick afterwards and said, ‘Stanley, I’m with you all the way, but I want you to know I generally peak about the 70th or 80th take’.”

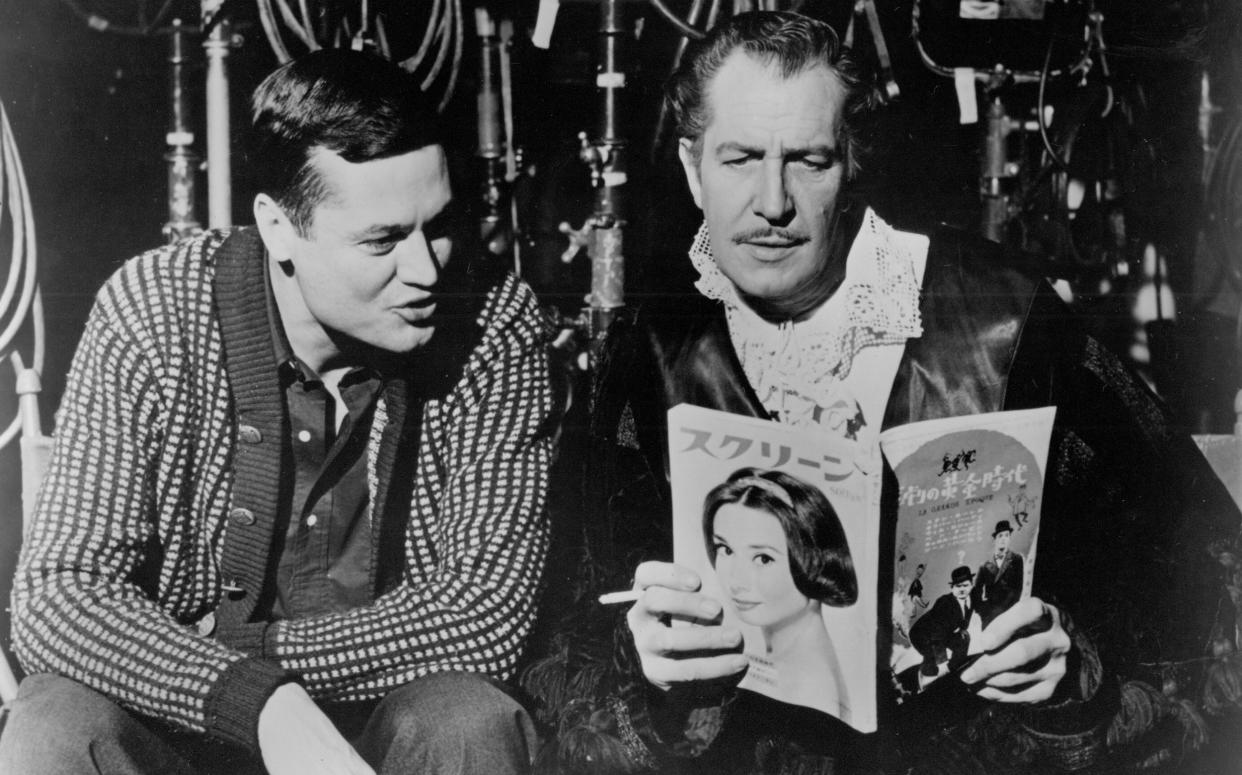

As the Corman name started to mean something, he was entrusted with higher budgets, and set to work on a more ambitious series of projects – eight period adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe between 1959 and 1964, all but one of them starring Vincent Price. Marked by striking use of colour and the wide screen – The Masque of the Red Death (1964) was even shot by Nicolas Roeg – they proved his mettle as a horror director, and hold up eerily well, as the definitive film versions of Poe. “I was learning on the job,” he explains, “so it wasn’t a specific change of technique, it was just learning, from film to film.”

How does he feel about contemporary horror films? “The cycle of horror right now is more explicit than when I was doing horror films. Indirection used to be the word. We suggested, we implied the horror by the cutting, camera movements and storyline, the horror was built up and built up. Now you’re more likely just to cut somebody’s hand off, and blood spurts across the screen, and you get horror that way. I think that will start to fade. I’ve been around long enough to see cycles start, build and come to an end. One director cuts off someone’s hand at the wrist, the next at the shoulder. It just gets gorier and gorier. The audience will react and turn away from this.”

In 1998, Corman published his autobiography, entitled How I Made A Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime. The title wasn’t his choice but the publisher’s. “I made more than a hundred films. And I lost a couple of times! I called the editor to say the title wasn’t really correct, and he said, ‘Has the title of every film you’ve made reflected exactly what was in it?’. I said ‘Use any title you like!’”.

One film that did lose money – Corman’s first flop, in fact – was his provocative 1962 drama The Intruder, starring William Shatner as a segregationist who arrives in a small Southern town to stir up racist animus among the locals. Not only did the crew receive death threats during the shooting of the film, once townspeople realised that Shatner’s character was anything but the film’s hero, but no one ended up coming to see it.

Corman was chastened. “It changed a lot of my feelings about filmmaking. It went to festivals and got really great reviews. One New York critic said, ‘The Intruder is a major credit to the entire American film industry’. And it was the first movie I made that lost money! I analysed it. Even though it got all the critical acclaim and so forth, it was too much of a lesson, trying to teach the audience. I had to get back to entertainment.”

“From that I developed a style. What I tried to do is make a film on two levels. On a surface level, it might be, say a gangster film. But on a subtextual level it might be about some thing or concept that was important to me. Maybe some people would understand the two levels, and maybe they wouldn’t, but for me it was the way I preferred to work.”

Corman devotees have a particular fondess for a film called The Terror (1963) – the quickest of his quickies, the cheapest of his cheapies, and a movie which demonstrates his hucksterish resourcefulness in extracting money from old rope. It was entirely filmed on leftover sets from other AIP productions from that year, such as The Raven and The Haunted Palace. Boris Karloff happened to be in California for a couple more days, having finished shooting the former. But I should let Corman explain.

“The whole picture was only made because it rained on a Sunday. We were supposed to be playing tennis. I called [screenwriter] Leo Gordon. We worked out a storyline, and Leo wrote just the two days in which I used Jack Nicholson and Boris Karloff, before Boris went back to England. Because of my Union commitments I couldn’t shoot the rest of the picture. Coppola shot a few days, and then he got a job at Warner Bros and his career took off. Monte Hellman shot a bit of it, Jack Hill shot a bit of it. And on the final day Jack Nicholson said to me, ‘Roger, every idiot in town has shot part of this picture, let me shoot a day!’ So I said, ‘Go on, be a director for a day.’”

“We cut it all together, and frankly, every director had a different interpretation and the picture didn’t make any sense whatsoever. I was shooting another picture, so I wrote a quick scene and had Jack Nicholson throw his co-star Dick Miller up against a wall. He said, ‘I’ve been lied to ever since I’ve come to this castle. Now tell me what has been going on!’ At which point Dick Miller explains what the picture has been about. People actually took it seriously and tried to figure it all out, but it had no plot whatsoever, that picture. That didn’t stop it making money.”

Newcomers to the delightfully grotty world of Corman’s filmmaking might be surprised to hear of his importance as an arthouse distributor, too. He made major successes in America of Fellini’s Amarcord (1974) and Volker Schl?ndorff’s The Tin Drum (1979), both of which won the Best Foreign Film Oscar, and Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1973), which was even nominated for Best Picture.

Though it’s hard to imagine the stony Swede directing, say, Teenage Caveman (1958), there’s actually a certain kinship in themes and style between Bergman and Corman, who delayed making The Masque of the Red Death because The Seventh Seal, with its strikingly similar vision of Death stalking the land, had just come out.

I tell him that Scorsese is on record, at least the way film chronicler Peter Biskind tells it in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, for preferring the Corman-directed Peter Fonda biker flick Wild Angels (1966) to Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957). Corman laughs. “I think Marty sometimes says things just to startle people. But we can certainly agree that Wild Angels had more action than Wild Strawberries.”