Phil Donahue’s Interviews With Early AIDS Patients Were a Master Class in Empathy

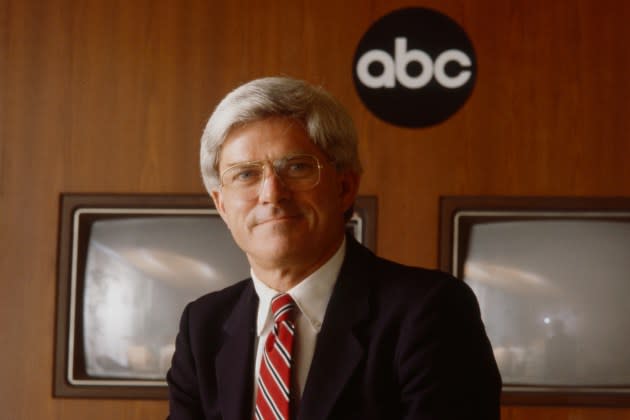

Many people who think of Phil Donahue, the pioneering talk show host who died on Sunday at 88, may conjure the caricatured image as played by Phil Hartman on Saturday Night Live in the early 1990s: roving around his set with a mic, interrogating his weeping guests at machine gun-pace, rolling his eyes and barking at audience members’ insipid questions. They think of him as someone with absolutely zero bedside manner, as Hartman does in this SNL segment featuring Donahue barking at a parade of sobbing domestic violence victims.

Donahue’s popularity at that point had been far outpaced by Springer’s more tawdry brand. When faced with a choice between watching Donahue, who at least attempted to inject his show with the spirit of journalistic inquiry, or brawls between diaper fetishists and incestuous shoe-sniffing 7-Eleven clerks, the public had opted for the latter.

More from Rolling Stone

In many ways, Donahue was the progenitor of the trashy talk TV show genre popularized by Springer and Povich and Lake and Jones. Particularly toward the end of his career, as he was trying to keep up with his competitors, his questions were often prurient and his interests skewed toward the taboo, with his audience constantly ooh-ing and aah-ing at an endless parade of fetishists and drag queens and junkies and crossdressers.

But I would prefer for his legacy to be defined by a moment much earlier in his career, during the early 1980s, when Donahue was still a Midwestern hometown hero broadcasting from Chicago and the show still maintained an air of journalistic sobriety. It’s an hour-long segment that has been preserved by the Museum of Classic Chicago Television, commercial breaks and all, that’s both a fascinating glimpse at the fear, confusion, bigotry and blind panic that marked the early days of the HIV/AIDS pandemic and demonstration of Donahue’s unique blend of curiosity, grace, and empathy as an interviewer.

The segment, “AIDS,” is dated November 17, 1982 — just one year after the New York Times had published its first article on the disease (“Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” attempts to explain a spate of mysterious illnesses involving young gay men in New York and San Francisco.) At the time Donahue’s show aired, a little more than 700 cases had been diagnosed, though tens of thousands of people had already unknowingly contracted the virus at that point. No one knew for sure how it was transmitted, nor was there a test to identify who had the virus. There were only a few things most people in America knew about AIDS: 1) it was primarily spread among gay men, and 2) it was horrific, debilitating, and fatal.

Aside from the LGTBQ press, there was very little mainstream media coverage of the epidemic. Most of the articles that were published, such as the Times story, were riddled with misinformation or inaccurately framed HIV/AIDS as an exclusively gay disease (even though the CDC had already identified a number of cases among heterosexual individuals). Reagan had not yet uttered the word in public, though just a month before Donahue’s segment aired, his deputy press secretary had answeredd a question about the “gay plague” by openly joking about how he didn’t have it.

It’s this context that makes Donahue’s hour-long segment so moving. In introducing his guests, including the legendary HIV/AIDS activist Larry Kramer, the NYC-based physician Dan William, and an AIDS patient named Philip Lanzaretta, Donahue is clear about the ambiguity surrounding the virus, admitting, “there’s a lot of mystery attending it, and we really don’t know the answers.” But he is also clear about the seriousness of the disease, as well as the shortcomings of the mainstream media and the medical establishment in failing to sufficiently address it.

“When the gay community has a problem, it does not get immediate enthusiastic establishment support for whatever might ail it,” Donahue says. “We do live in a homophobic nation, and they are further impeded in their effort to find out what is killing their friends, by what some people might think is God’s angry attempt to punish the [slur for gay men].” In so explicitly condemning the homophobia of the establishment — and, as will be clear later in the segment, Donahue’s own audience — Donahue stood virtually alone among his peers in the mainstream press.

Throughout the segment, Donahue is characteristically probing and pointed in his questions. Not all of the interview has aged well: at one point, he pushes back against Kramer’s assessment that AIDS transmission is not specific to the gay community, by saying “the amateur diagnostician would be tempted to conclude that gays are doing something intimately that the straights are not doing.” (We now know, of course, that Kramer was absolutely correct, and HIV/AIDS is transmissible via bodily fluids such as blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk.)

But he is also open-minded, empathetic, non-judgmental, and utterly withering toward ignorant audience members. At one point, he starts yelling at one particularly homophobic caller, rolling his eyes and shouting at the hypocrisy of her railing against the “lifestyle” of gay men while heterosexual men harass and abuse women; he also yells at another audience member for making homophobic comments about William, who is gay. Over and over, Donahue makes the point that were HIV/AIDS afflicting white heterosexual Americans, it would generate all of the resources of the medical community, forcing his audience members to confront their own biases in a way that few members of the mainstream media, let alone middle-aged white male Catholic journalists, were doing at the time.

Throughout his career, Donahue would continue to highlight the plight of HIV/AIDS patients. In 1986, he shot a devastating segment at St. Claire’s Hospital in New York City, holding weeping patients in his arms at a time when many healthcare professionals were too scared to even touch them. (Many of the patients highlighted were also women and heterosexual men, which had the effect of showing Americans how wide-ranging the epidemic was.) In 1990, he served as a pallbearer for the funeral of Ryan White, a hemophiliac who contracted HIV/AIDS following a blood transfusion and died at the age of 18. But it’s Donahue’s 1982 segment that truly showcases the brash, fearless, empathetic, impatient, occasionally blundering journalist he was.

Best of Rolling Stone