Nashville soul legends celebrate legacies at Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

The 20th-anniversary revival of the Country Music Hall of Fame's multiple award-winning "Night Train to Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues Revisited" exhibition is best characterized not by its initial founding.

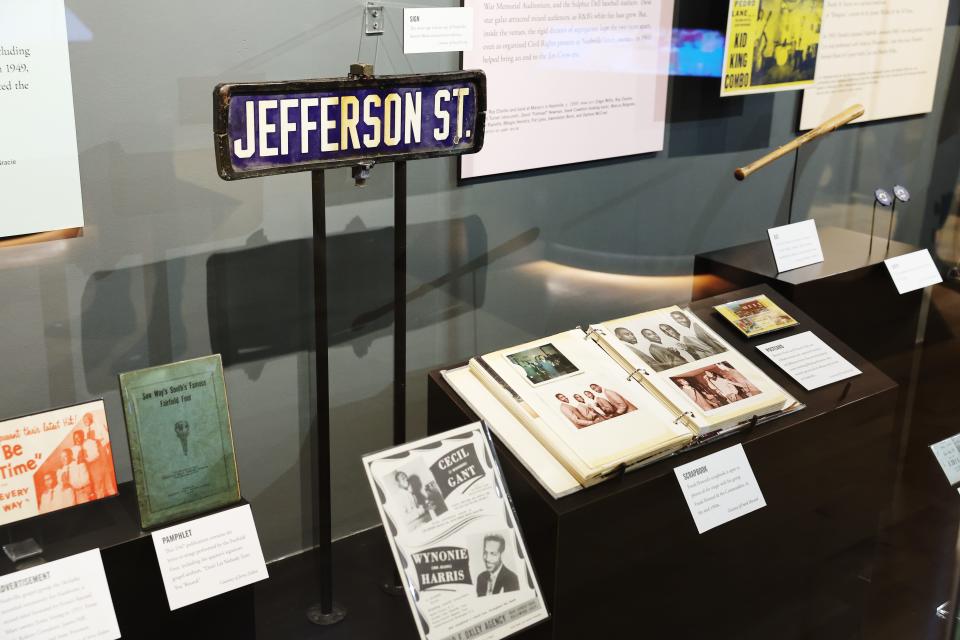

However, in discussing living in the retro-fitted and future-forward present, an exhibition linking Nashville's pioneering R&B scene of the 1950s and 1960s that included names like Ray Charles, Hank Crawford, Bobby Hebb, Jimi Hendrix, Etta James and Little Richard with Music City's eventual evolution into a world-renowned music center becomes apparent.

The exhibition—which runs from Apr. 26, 2024, through Sept. 2025—will include recently discovered artifacts and photographs central to Music City's influential R&B past. The cost of the exhibition is included with museum admission.

Septuagenarian performers and Nashville residents like Jimmy Church and Frank Howard exist as not just historical footnotes beloved by underground soul record collectors worldwide. Instead, they are living legacies whose words breathe broader life into stories whose impacts—because of the effects of racism and social injustice—have been narrowed for half a century.

While at the exhibition's April 25, 2024, re-opening, Church and Howard spoke at length with The Tennessean about the moment's impact upon their careers and lives as they are recast and reexamined in broadened presence and scope.

Renown increases for Nashville's soul legacy

Both artists now live lives where their work has achieved Grammy-winning renown (Best Historical Album, for 2004's compilation that accompanied the initial opening of the exhibition, produced by Michael Gray and Daniel Cooper, with the assistance of audio engineers Joe Palmaccio and Alan Stoker) and worldwide appreciation that has afforded them underground and mainstream appeal that on some level is equal to artists working in other areas (like Memphis' Hi or Stax Records and performers like Al Green, Issac Hayes and Otis Redding, for instance) or with greater reach.

Also, 2004's original exhibit earned the museum a Bridging the Gap Award from the Nashville chapter of the NAACP in 2006 and a major 2023 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that returned elements of the exhibition to the internet for free.

Howard discusses the bittersweet excellence of how North Nashville's corridor thrived during Music City's violent struggles with segregation, providing a daily and weekly respite from the frustrations of American life during the era.

"As Nashville developed into a major recording center, it did so against a background of urban change and at a time when racial barriers were tested and sometimes broken on bandstands, inside recording studios and on the airwaves," adds Kyle Young, CEO of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, via a press statement.

North Nashville's uniquely thriving decades of success

During the same time frame that Howard and his band, The Commanders, gained renown playing the myriad of nightclubs, radio stations and television shows afforded Black talent in Nashville during the early 1960s, Black commerce in non-segregated Northern areas like Detroit gained relevance as Berry Gordy's Motown Records became the self-described "Sound of Young America."

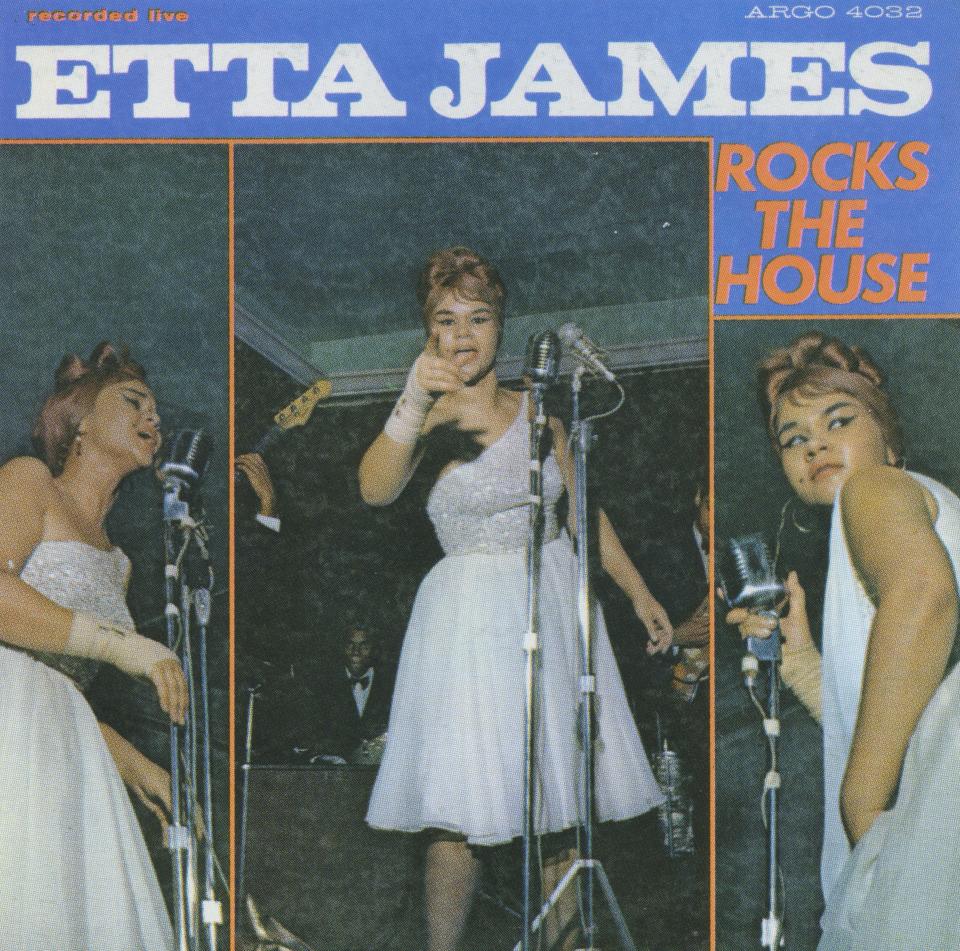

He name-drops DJs (and eventual record executives for Nashville's Sound Stage 7 Records) at Nashville's nationally broadcast and 50,000-watt WLAC-AM like Bill "Hoss" Allen and John "John R." Richbourg, New Era nightclub owner and entrepreneur William "Sou" Bridgeforth as curating scenes that locally, then nationally valued Nashville's artists like himself, Church and guitarists like Jimmy Jones and Jimi Hendrix, among many, as being as talented as artists traveling through the area on the all-Black "Chitlin' Circuit" like James Brown, eventual Country Music Hall of Famer Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, Jackie Wilson and Etta James, who released a legendary live album recorded at Bridgeforth's New Era Club in 1963.

By 1964, Nashville's success pushed WLAC-TV to (five years before Chicago's "Soul Train" debuted) use WLAC radio competitor WVOL's radio executive and program host Noble Blackwell to host the "Night Train to Nashville" program highlighting acts like The Avons, Church, The Hytones and The Spindells.

Later, WLAC's Gab Blackman counter-programmed with "The!!!!Beat," a Dallas-recorded color-television-enabled and nationally syndicated program hosted by Hoss Allen. It was the result of a business partnership between Blackman and the enterprise behind Grand Ole Opry favorite and country music star Porter Wagoner's TV program.

Howard highlights how the scene fostered a culture where aspiring Black music professionals like Hendrix (who was, alongside Billy Cox, AWOL and arriving in Nashville, via Clarksville, from the United States Army's Kentucky-based Fort Campbell in 1961), Black college students at nearby Fisk University and Meharry Medical College, and local residents working days downtown and oftentimes engaging in protests under difficult racial circumstances were also able to achieve success in crowds largely comprised of their fellow Black Nashvillians in less socially trying conditions.

Howard's local schedule often saw gigs three nights a week playing at clubs in a three-mile radius near Nashville's Interstate 40 including the Club Baron, Del Morocco and Stealaway, plus occasionally for George Jones' close associate Bertie "Pee Wee" Johnson's West Nashville-based Pee Wee’s Place nightspot often alongside performers including Fats Domino, Chubby Checker and Jerry Lee Lewis.

He then recalls, even deeper, how Nashville's scene achieving renown throughout the midwest and South afforded acts popular in North Nashville the ability to tour in locales great and small as far afield as Chattanooga and Paris, Tennessee, Owensboro, Kentucky and Evansville, Indiana, among many cities and towns.

Jimmy Church's living legacy

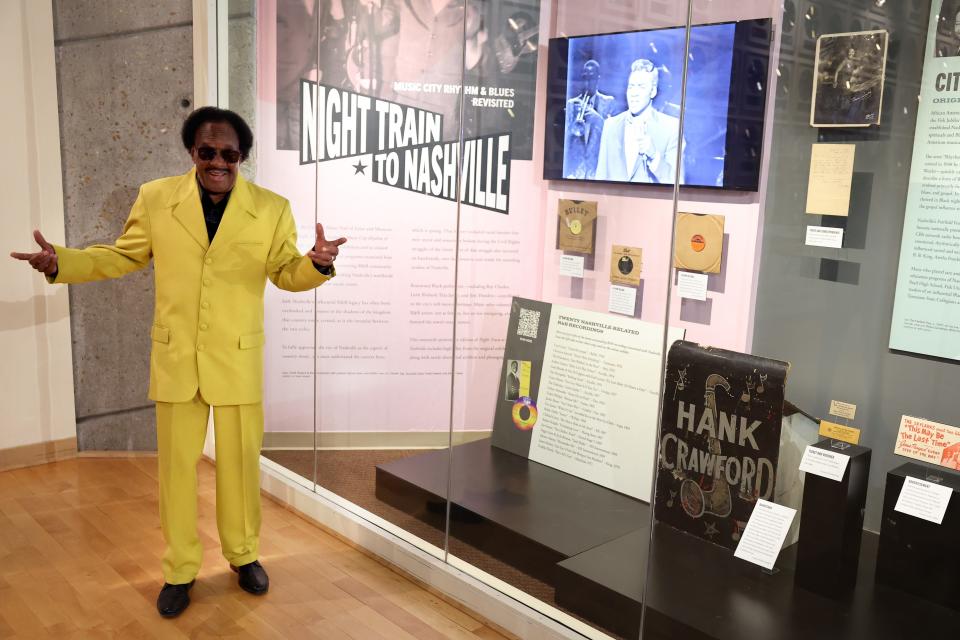

Church, sharply dressed in an iridescent yellow suit, is less talkative.

"For 60 years, Jimmy Church has set a standard for dance and soul nightclub acts involving having a line of people waiting to get into a club that went around the block and inviting younger acts to open for him," says Howard.

"He made great money here and drove around town in a Cadillac El Dorado while artists like myself were working 9-to-5, then three shows a week, plus doing sessions for TV shows like 'Night Train to Nashville' and 'The!!!Beat,' or playing in studio sessions for the national artists who were coming to town recording for Sound Stage 7 Records."

As a leader of his own band and a member of the King Kasuals, Church played with Hendrix and Hendrix's eventual bandmate, Billy Cox. He was also regularly featured on Nashville-to-nationally renowned television programs like "Night Train" and "The!!!Beat" and eventually became one of the South's most in-demand cover band artists.

His legacy speaks for itself.

I've forgotten half of everything I knew from back then," he jokes.

"But it's important to keep the music alive. Younger generations don't realize the power of the bands we had (in the 1950s and 1960s). We were talented musicians who also were great entertainers who kept a culture alive, nightly."

A legacy endures

Nashville became the South's first desegregated city on May 10, 1960. By November 2, 1967, District Judge Frank Gray had decided to build Interstate 40 through an area once called "Black Wall Street."

The separation of Black people from commerce forced the eventual closure of Black-owned businesses in the area, including the Club Baron, Club Del Morocco, Maceo's, Stealaway, and more.

Five decades later, though in a much smaller venue, that legacy endures.

Currently, Howard describes the scene at Carol Ann’s Home Cooking Café—a restaurant and performance venue a five-mile drive west of Nashville International Airport—as, via acts including Church and himself, a free Tuesday evening event that is "a fun time for everyone."

Howard describes the power of reviving the Country Music Hall of Fame's "Night Train" exhibition as extending what happened when, after the original exhibition opened 20 years prior, it spurred him to return to secular music after taking his art, alongside his brothers, in the direction of gospel music.

"Once I started getting the calls from Germany, Japan, all over the world, about how far our original records—that were on the compilation—had grown in renown and on the charts, I realized something special was happening."

Church, keenly aware of a similar occurrence, nods in agreement, then offers a sage comment about the exhibition's revival, in total.

"All things considered, even 20 years later, it's surprising to see Black, North Nashville, R&B culture celebrated and kept alive in country music's Hall of Fame. It's amazing to realize that, forever, everyone will know the power of the impact we had as a foundation of music in this city is unforgettable."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nashville soul legends celebrate legacies at Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum