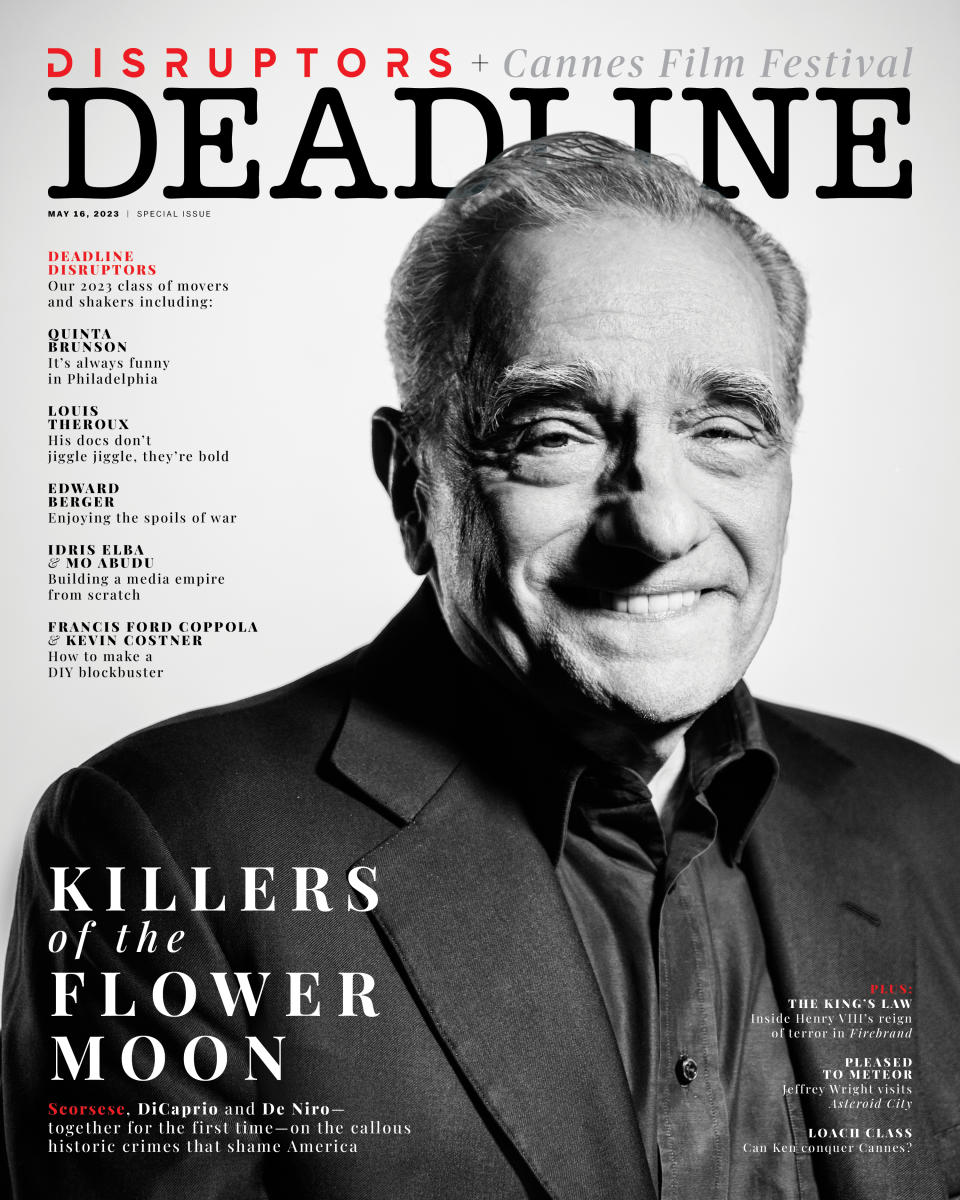

Mavericks Francis Ford Coppola And Kevin Costner On Risking Their Fortunes Bankrolling Passion Pics ‘Megalopolis’ And ‘Horizon’

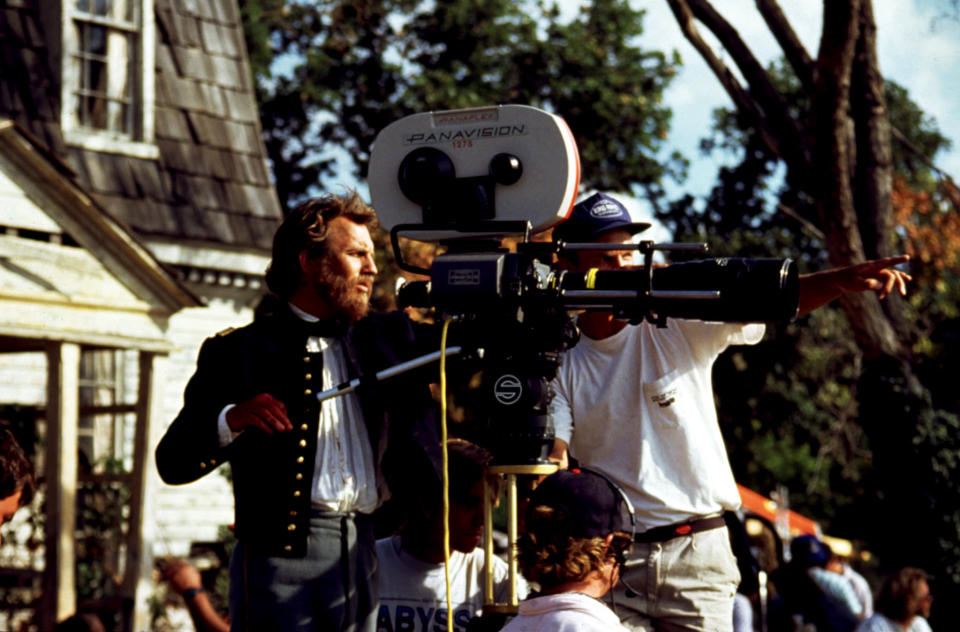

It’s a spring afternoon, high up in the mountains of Moab, Utah, and Kevin Costner looks up at the sky. Rough weather is starting to roll in and he needs to get back to work and bank some more scenes. After all, it’s coming out of his pocket. The project is called Horizon, the first of four films set in the pre- and post-Civil War expansion of the American West. It is his most sprawling epic since Dances With Wolves, which he also part-funded, and which brought him seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Investing in himself isn’t just frivolous affectation for Costner. It’s in his DNA. “I’ve mortgaged 10 acres on the water in Santa Barbara where I was going to build my last house,” he says. “But I did it without a thought. It has thrown my accountant into a f*cking conniption fit. But it’s my life, and I believe in the idea and the story.”

More from Deadline

RELATED: Kevin Costner’s Career In Photos

Some days later, down in Atlanta on a chilly evening, the crew waits for Francis Ford Coppola to come out from the Silverfish, the trailer where he has shot most of his films — their titles are painted on the exterior passenger side wall — and a portable residence that looks a bit like an old toaster. Megalopolis is in the home stretch, and the scene is anarchy as factions argue about the future of a New York-like city that has to be rebuilt after a seismic event.

Among those waiting are Shia LaBeouf and Dustin Hoffman. Also in the wings are Jack Black — who’s just come to watch Coppola work — and Leaving Las Vegas director Mike Figgis, who’s shooting a documentary about what could be the 84-year-old’s last big movie. Coppola finally emerges, wearing a cream-colored suit, scarf and black beret, and the crowd parts for him. I tell him later this must have been how General Patton did it, and he laughs. Patton was a seminal figure in his career: Coppola got the first of his five Oscars by writing the screenplay for Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1970 biopic.

RELATED: Francis Ford Coppola’s Career In Photos

That night, Coppola recalls, he watched the Oscars from New York, where he struggled with The Godfather, the studio shadowing his every move. He was with his friend Martin Scorsese, and after hearing Coppola’s name called, Scorsese said, “There’s no way Paramount can get rid of you now.” That night’s win launched a career as a filmmaker and entrepreneur that allowed Coppola to spend $100 million of his own money to finance Megalopolis when no one else would.

Meanwhile, between putting up cash and deferring all his fees for Horizon, Costner has done much the same thing: Horizon has become his obsession, and presumably has created the stalemate on Yellowstone that likely will lead to his exit after a clash with showrunner Taylor Sheridan. (Costner declined to comment on that evolving situation.)

Costner and Coppola are a rarity in Hollywood: proven mavericks who will put their money where their mouths are. Deadline brought the two together to discuss what it means to believe in your vision so much that you are willing to risk a fortune to see it through.

DEADLINE: Each of you previously put up your own money to make a movie or two happen, but these are $100 million-plus productions. Kevin, how did you come to be on the hook for Horizon?

KEVIN COSTNER: The story will speak loudly to Francis; others will scratch their heads. I commissioned this story in 1988. Single movie, two-hander. A conventional Western with a beginning, middle, and end. I couldn’t get anybody to make it. Then, right after I made Open Range and it performed pretty well, I had a chance with Disney. We had a $5 million difference. They had had a lot of money success with Open Range, but a $5 million difference kept them from making this movie. Now, I’m stubborn, and I think probably Francis is too. Eight years later, I started thinking about the story, started writing with a partner, and it ended up being four screenplays. So I reverse-engineered everything from 1988. I thought it was really good. But I still couldn’t get anybody to make it.

DEADLINE: You believed in it enough to gamble your waterfront property?

COSTNER: At the end of the day, I’m a storyteller, and I went ahead and put my own money into it. I’m not a very good businessman, so, scratch your head, if you will. I don’t know why, but I have not let go of this one. I’ve pushed it into the middle of the table three times in my career and didn’t blink. This is my fourth. And probably one of the few people in the world I could talk with about this would be with Francis.

DEADLINE: Francis, does any of what Kevin said sound familiar to you?

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: It does. For me, when you do go into the great unknown, you don’t want to say, “Oh, I wish I had done this or that.” You want to say, “I got to do it.” And you’ll be busy thinking of what you did that you wanted to do, that when death comes, you’re not going to even notice it.

COSTNER: That’s how I feel about it.

DEADLINE: The themes of Megalopolis have been in your mind for decades, also.

COPPOLA: I’ve always operated under this vague idea of trying to do stuff, because if you don’t achieve it, it’s no worse than if you didn’t try. At least by trying, you have the possibility you could pull it off. One thing about Kevin, if you were to list all of the really great directors of the world, and you looked at who went from editor to director, or from assistant director to being the guy in charge, which do you think has the highest ratio for making great directors, three to five times more than any category?

DEADLINE: I would guess DP or actor?

COPPOLA: Actor, by far. I mean Charles Laughton, Laurence Olivier and, in the old days, G. W. Pabst. Kevin is an example of a great tradition. The reason is that when it comes down to the two essential elements of cinema, like water is to hydrogen or oxygen, cinema is acting and storytelling. Since the highest goal is great storytelling, actors are among the few who search for truth throughout cinema history, from the silent age to now.

DEADLINE: Kevin, how helpful was your acting background when you jumped to filmmaker?

COSTNER: I started as a stage manager at Raleigh Studios and didn’t really tell people that I wanted to be an actor because nobody wants to be around a pining actor. But I kept my eyes open. Everything came to me late. My first [acting] check, I was probably 28 years old, and it took me six years to get my SAG card. Then I got four or five movies under me and wanted to direct this movie that I had a friend of mine write, Dances With Wolves. No one would make it. It went around twice to the studios.

I’m a plodder; it took me a long time. I didn’t burst on the screen as a 19-year-old. When I did my first five movies as an actor and started to direct, people said, “Whoa, you’re going pretty fast.” I thought, ‘Man, I just got here.’ But I had my eyes open for years, watching. And watching what Francis did, and some other smart people. I studied it. Because everybody tries to make a great film, and a lot aren’t good at all. Look at the movies that stand the test of time. There are moments, words spoken, and gestures that you’ll never forget. You’ll find them in Francis’ movies and other movies I studied.

DEADLINE: What’s the difference between the mediocre ones and the classics? Authorship?

COSTNER: You feel like you’re in the careful hands of a real storyteller. My background is hunting and fishing. I’ve sat around campfires with my father and watched older men talk. I got to know who the real storytellers were. Time doesn’t matter if your story is interesting.

DEADLINE: Francis, you had famous fights with Paramount on The Godfather. Financing Megalopolis makes you the studio.

COPPOLA: You used the word authorship — the idea of auteur theory, where there’s one voice. But even that one author is basically standing on the shoulders of previous giants. There’s no avoiding it. So authorship only means the film is honest to the theme and the premise. It has to be personal, real; it can’t be a synthesis of what people have decided would be a good formula for a movie. I acknowledge fully that any film I make is filled with things I learned from watching the greats that came before me.

COSTNER: When you go into a studio and walk down the halls, you see all these posters of the movies they made. Unless you’re the filmmaker, you really can’t understand, forensically, how those movies went down: who almost killed it, who could have ruined it, who tried to ruin it and now puts it front and center on their wall. We go in brave and certain about what we feel, but those voices can get inside you. There’s fear about doing something that’s a little bit original. Like, we know in a romantic comedy that, first base, they gotta hate each other. Second base to third base, maybe there’s something between them. And then you get to home and you have your movie. There’s a formula in comedy. Nothing wrong with the formula. But God curses a person like me or Francis; if we decide to do a straight-up comedy, we’re gonna hit those bases, but we might hit them in our own way.

COPPOLA: There is a first base, a second base, and a third base, but not always in that order.

COSTNER: And God forbid they go test screen it. Then holy hell breaks loose. That’s when the movies are at their most vulnerable when we start giving them scores. Because, really, these are emotional experiences, not intellectual ones. I know, absolutely, that because of testing, studio executives live or die depending on what happens Friday night. But movies can have a life long after that. I believe in the life of the movie more than I believe in the opening weekend, so every decision I make has to do with that.

DEADLINE: Francis, you’ve said financing Megalopolis wasn’t about creating a piece of commerce or winning yet another Oscar. It was to leave behind something future generations could find and discuss. What was the conversation like for you, ending with selling part of your wine holdings to do this?

COPPOLA: Oh, I didn’t do it that way. I recognized that, at my age, I didn’t have people to run all these businesses that I not only had started but was running. My children have been an enormous help in the wine and other businesses, but they have their own careers. Sofia’s not gonna suddenly run a big wine empire, or Roman. The wine business has changed. A lot of consolidation and distributors have gotten bigger and fewer. To be successful in the wine business today, you have to be big enough to get the cooperation of the distributors. That is in the billions now, not in the hundred millions. Although my one wine company was the 13th largest in the country, it was on the edge of being unable to survive if it didn’t get bigger. At my age, I wanted it to be acquired by people I knew and liked. By combining with them, we became the fifth-largest winery. Which means we’re in the game. In the course of that, I realized I had created a holding of value in that company, which I could go and turn into money and make the movie I wanted to make.

So I won the bet. But I am grateful to be in the position to be able to make a film that haunts me and that I feel will be wonderful, that will shed light on the subject of what the future might be like and what human beings are really like. I am as happy as I could be.

DEADLINE: Francis, you took a deep plunge with Apocalypse Now, and you put it at Cannes as a work in progress, and the film shared the Palme d’Or. You told me your gamble was to stop an overwhelming negative narrative that you would never finish the film, or that it would be the biggest flop in decades. A trade report on Megalopolis painted a picture of an out-of-control production. Aside from déjà vu, how did that affect you compared to the attacks on Apocalypse Now?

COPPOLA: Well, Apocalypse Now was out there being edited for months and months and months. And because it had been made in the Philippines, it was sort of mysterious. [With Megalopolis]

it was much the same thing. A rumor starts out; there was a report about chaos. But the source was no source.

From my point of view, I was on schedule, which, on a big, difficult movie, is hard to do. I love my actors, and there is not one of them I would change. The movie has a style that went beyond my expectations. That’s sincerely how I feel. The most important thing is the life the film might have when eventually it cuts together and blossoms. On Godfather II, that happened three weeks before a devastating preview. And Peggy Sue Got Married had a terrible preview, then two weeks later, it came together. Movies can change their chemistry.

COSTNER: It’s tough when you put a pencil in an audience’s hand. It’s really not what the experience is about. I know when I was making Dances with Wolves, they were calling it “Kevin’s Gate”, even though they didn’t know that I put all my money into this thing, and I actually asked three other directors to direct it before me.

DEADLINE: Why didn’t that happen?

COSTNER: They each had kind of very pronounced ideas about what they wouldn’t leave in the movie. They’re very well-known directors. One said I should get rid of the Civil War sequence and start with them out there in the middle of nowhere. Another said, “The white girl, it’s a cliché.” Well, it wasn’t a cliché. In the West, slaves were traded. They were very valuable in the commerce of the West. I finally directed it by default. What I knew was, I wasn’t as good as any of those other directors. But I wasn’t gonna leave anything out.

You just have to trust what you think you’re doing. When I go to a theater, I just sit down in the dark, have the curtain open, and go on the ride with this storyteller.

DEADLINE: And, in my opinion, those very Civil War scenes are really among the most indelible of Dances with Wolves…

COSTNER: But it was an easy cleavage. Somebody figured out how to get 10 minutes out of the movie. Congratulations. You’re a genius!

DEADLINE: Francis, you told me your wine business has made you more than your films. Kevin, a couple years ago, you had an invention that helped clean oil spills by separating water from the oil. How does the experience of taking an entrepreneurial risk help when you are staking $100 million in Horizon and Megalopolis?

COSTNER: It didn’t for me. It was just a feeling.

DEADLINE: Francis, how about you?

COPPOLA: Oh, I’ve been displaying this behavior for 70 years, trying to learn about cinema. I’ve found the best way is to make a film you have no idea how to make because then the film will help you. And the film won’t tell you which way to go. I like that. I’ve enjoyed my career. As for the risk stuff, what are you risking? You’re risking something that you’re lucky to have, which is the ability to finance a movie. I had that fall in my lap. I wasn’t entrepreneurial for any reason other than that it was fun. I like having fun with people. And that still is the most important thing, and that’s what makes an audience enjoying the movie a great thing to be part of. We’re all there, going to see Lawrence of Arabia together.

COSTNER: I’m not a gambler. People might look at this and say, “Oh, this is a gamble.” And I go, “Well, I guess it is, but do I want to go to Vegas and gamble?” No. I’m not that kind of gambler. I gamble on the love of story. I’m gambling on people, in a sense. I can’t make them go to the theater, but if they get there, I’m going to try to take care of them the best I possibly can. That’s what I count on, like that guy at the campfire.

DEADLINE: Francis, you went into Chapter 11 after One From the Heart. It took a number of movies to make you whole. Bankruptcy is a worst-nightmare scenario for most. What was the biggest lesson that you learned about gambling on your vision and failing?

COPPOLA: It was tough to go through, but I felt I was young and I had gone from being penniless to being in a position of being able to lose so much money. I’m obviously not young now. I couldn’t do it again, nor would I care to. If I’ve noticed anything from this interview, it has been very positive, with neither of us moaning, groaning, or complaining. We are happy in saying we’re doing this because we enjoy it so much.

DEADLINE: There was a time of uncertainty when you feared Apocalypse Now might ruin you and cost you the Inglenook vineyard. Your pal George Lucas was flush with Star Wars money, said he would buy it from you, hold the note for 10 years and sell it back at same price. This was after you went to bat for him on American Graffiti when Universal hated the film. Outside of James Cameron helping Guillermo del Toro secure the funds to get back his dad who’d been kidnapped in Mexico, this is exceptional largesse. Quantify a friendship like the one you’ve had with Lucas.

COPPOLA: In a nutshell, if someone said to you, would you rather have a billion dollars or a billion good friends? Friendship is far more valuable than money will ever even begin to be.

DEADLINE: Kevin, have you ever had that kind of camaraderie with somebody in the film business?

COSTNER: No, I haven’t had anybody like that, although on this particular movie, I put in all this cash, and I basically deferred my writing, my producer, directorial and my acting fees. So I have an enormous amount in this. But I had two guys from outside the business come in and say, “We’ll make a movie with you.” And it really scared me, because I’m more afraid for my friends’ money than my own. And that’s why, on these first two, I deferred everything [laughs]. It’s not the smartest move, but I started this conversation by saying I’m not the greatest businessman. I believe in the movies, the power of them, the longevity. By putting my own money in it, I will chase this movie with my partners the rest of our lives. I can’t put my own money into something and have somebody else be in control, because, at the end of the day, the money isn’t as important to me as the movie.

DEADLINE: Francis, you’ve taken these big swings, your wife Eleanor by your side the whole time, directing that doc about the hardship-making Apocalypse Now. I remember being amused when you told me that after you put your family through some hardship, you gave her $10 million so she’d never have to worry about money again. And then you asked for it back a week later for a business opportunity.

COPPOLA: Well, yeah, there have been highs and lows [laughs]. I’ve been married to one woman for 60 years now, and I think taking that money back to buy the rest of Inglenook was one of my smarter moves. My feeling is that as long as I make her happy, I’m doing OK with her. My children, also. I’m risking money that I made on a big risk that everyone told me not to do, but I did anyway. It wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t taken some of my own advice. Sometimes my wife’s advice is very useful. When she says no to something, that’s usually a good reason to do it [laughs]. My wife is valuable to me in many, many ways, but that is one of them. Did you know that I once bought the Chateau Marmont for $6 million?

DEADLINE: When was this?

COPPOLA: Around the time of The Godfather Part II. The reason you probably don’t know is because my wife didn’t want me to do it. And I got out of it by invoking a termite clause.

DEADLINE: Kevin, when will we see Horizon? Warner Bros and New Line are releasing it?

COSTNER: Correct. I hope it comes out in the fall. I’d like to take it to the Venice Film Festival. That’s what I want if I get the chance. I love going to Europe, and I’d like to put that out there and let people know that’s what my hope is.

DEADLINE: And you, Francis? Megalopolis needs a distributor, and there are a lot of them wandering along La Croisette at Cannes.

COPPOLA: I’m not looking for a distributor as much as a distribution partner because the movie has already been made and financed. It has to be in theaters for its initial opening; it’s the way it’s designed to look and behave. I’m most interested right now in arriving at the edit when it’s the film I want. My guess is it’s not coming out this year, so we’ll see.

DEADLINE: Last question. Kevin, the year that you won all those Oscars for Dances With Wolves, it was quite an Oscar year. Francis was up for Best Picture and Director for the third Godfather, and Martin Scorsese was up for Goodfellas. What do you remember about winning in such a great year for movies?

COSTNER: I was overseas when the movie came out, so I didn’t see what was happening, even in LA. You hear your name called, and it’s a bit of a blur. It’s a forever moment, but it’s just a moment. I was so grateful to the Academy, but I’ve tried to not let awards inform my work. I make these movies for people, not for myself. I author every moment in them as if I’m protecting their experience, protecting the time that they take to come to the theater. That’s how I look at it. But I’ll tell you what. I’m never gonna do this again [laughs]. I’m never putting my f*cking money in another movie after these four.

Best of Deadline

Cannes Film Festival Photos Day 3: Harrison Ford, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, ‘Le Regne Animal’ & More

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.