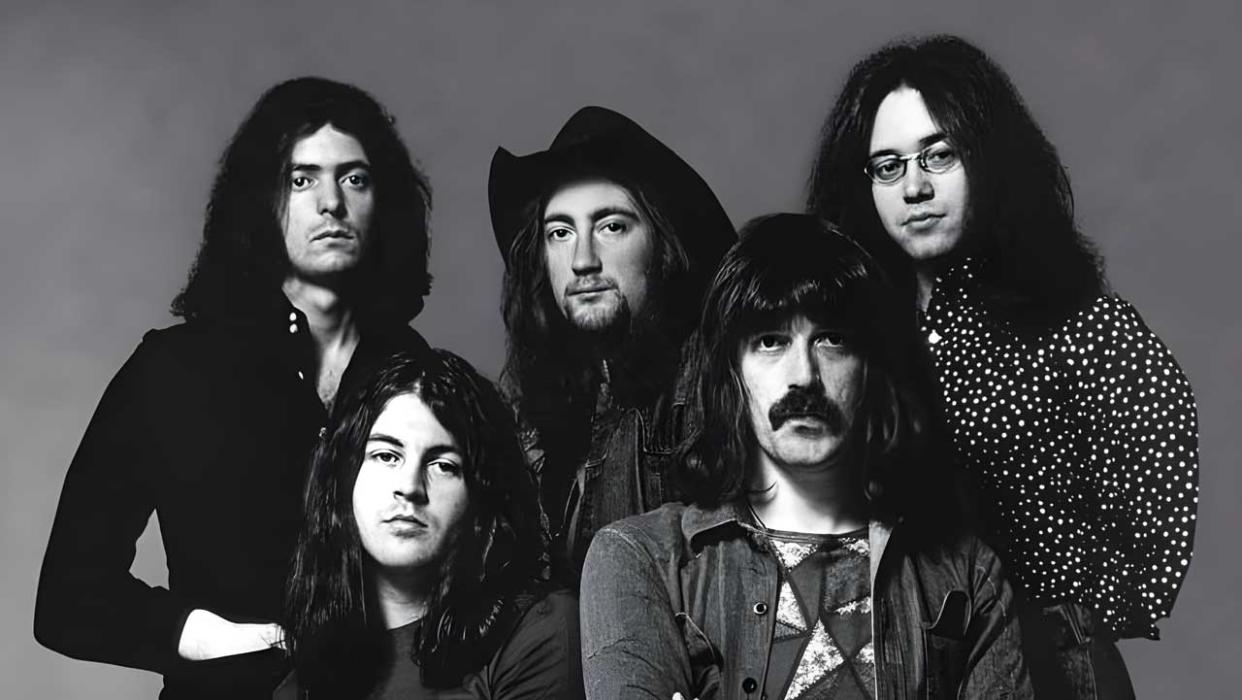

The making of Deep Purple's Machine Head: "Smoke On The Water only made it onto the album as filler"

Deep Purple's Fireball was the second album recorded with the Mark II line-up. It was another No.1 hit in the UK, but despite its success there was a nagging feeling within the band that the best was yet to come.

As 1971 drew to a close, it was time for a change of scene.

Roger Glover (bassist): We needed to make another record, and we’d become pretty successful, and accountants and lawyers and management said: “You know, if you record outside of England you pay a different tax rate.” And that’s the reason we were in Switzerland. It could have been Germany or France, anywhere as long as it was out of England.

Jon Lord (keyboard player): We’d heard the Rolling Stones had a wonderful mobile studio, so we contacted them and we were able to get hold of that. And the reason we went to Montreux was because we were going to be in America at the end of 1971, but Ian Gillan got ill. It was hepatitis, I think – which was the disease to have at the time.

Ritchie Blackmore (guitarist): It was a very fashionable thing to have. Gillan went down with it first. And then we went back to America to do the shows we’d cancelled. And then I got hepatitis, and I ended up in a Harley Street hospital, and had about two months off. That gave me some time to write something. I came up with Space Truckin’, Smoke On The Water and stuff like that.

Ian Gillan (vocalist): Fireball gave us a chance to actually bring out what I always call the funk in the band, instead of just pure English rock. However, when we got to doing Machine Head, there was a lot of pressure to do what most people saw as a follow-up to In Rock. We’d got to get back to doing that rock stuff, and that was pretty much how we approached it.

Lord: A dear friend of ours, called Claude Nobs, who ran the Montreux Jazz Festival, said: “Why don’t you come to Montreux?”

Colin Hart (Deep Purple tour manager): Machine Head was supposed to be recorded at the Montreux Casino, and we were supposed to be starting after Frank Zappa played a gig at the casino. They [Purple] were going to record where the casino concerts were held.

Ian Paice (drummer): We went down to Switzerland, and everything went from being under control and knowing what we were going to do to, literally, going up in flames.

Hart: The Stones’ mobile was parked next to the casino. The Frank Zappa show was the night before and we’d all been invited. It happened just like it did in the song [Smoke On The Water]. Some idiot fired a flare gun into the suspended ceiling and it just erupted into flames.

Claude Nobs (Montreux Festival organiser): The ceiling was made from some very flammable things, that you could not do any more these days. And the air-conditioning system started to get crazy because there was more and more heat coming in.

Blackmore: Frank Zappa was very nonplussed. He stopped playing and said: “It appears the roof is on fire, and we have to vacate the premises and we’ll do it in an orderly fashion…” And at that point he threw down his guitar and jumped out of the window.

Paice: Within minutes it was an inferno, flames hundreds of feet in the air. Back at the hotel, Roger and Ian saw this pall of smoke drifting across Lake Geneva.

Hart: We all ended up standing on the edge of the lake, watching the place go up in flames. Our concern was for the mobile studio that was gently roasting. Someone tried to get it out, but the water from the fire department’s hoses meant it was bogged down. It was getting hosed down with water on one side, while the other side was blistering. We thought it was all over. But Claude Nobs took it all so matter-of-factly: “Don’t worry, we’ll find somewhere else.”

Nobs: We first went to The Pavilion [theatre and ballroom], and I said to the guys: “We can record only until ten o’clock in the evening, due to the noise carrying across the mountains. We’ll finish it then and go out for dinner at ten p.m.” Of course, the first night they finished at four in the morning.

Paice: The first track we laid down – and the last to be finished – was Smoke On The Water, before we knew what it was going to be called. There was no sound-proofing and we were recording at night. A hell of a racket!

Blackmore: We did Smoke On The Water there, and the riff I made up in the spur of the moment. I just threw it together with Ian Paice. Roger Glover joined in. We went outside to the mobile unit and were listening back to one of the takes, and there was some hammering on the door. It was the local police, and they were trying to stop the whole thing because it was so loud. We knew that they were coming to close everything down. We said to Martin Birch, our engineer: “Let’s see if we have a take.” So they were outside hammering and taking out their guns… It was getting pretty hostile.

Martin Birch (engineer): It was about two in the morning, the neighbours were complaining. We locked all the doors. I mean, literally, it was ‘da-da-da! Bang, bang’, “polizei, polizei” “Piss off!” ‘Da-da-da’. So we had to get the track down before the police broke in and chucked us out.

Glover: About a day or two after the fire, I’d woken up in my room, and before I’d even opened by eyes I said some words out loud. It was almost like an echo in the room: “Did I just say something out loud?” I must have. And what did I say? “Smoke on the water.” I went down to breakfast and I said to Ian: “Oh a title came to me today: Smoke On The Water.” There’s a great photograph, it’s taken over Ian’s shoulder, and he’s got a notebook and the first two verses of Smoke On The Water are written, and the third one is yet to be written, and I’m opposite him. And that’s actually how we wrote it.

Paice: The recording was so quick. I really don’t remember it. Music was written before, but not the vocals – there’s no way Smoke could have been written unless the casino fire had happened.

Gillan: I can’t remember the solo being recorded, but it’s very good – full of character and technique, normal for Ritchie.

Nobs: By now I’d had to find them another place. I found the Grand Hotel. So we took a gangway in the middle of the hotel, and put some absorbing material in there – about a hundred mattresses – to get the sound right.

Gillan: We had to make it up as we went along. I remember equipment being set up all over the place to get some separation without us turning down. It was surreal when I think back, but normal at the time. You did what you had to do. The truck was too far away and it was bloody cold, so no one was keen to listen to anything until we felt it was right.

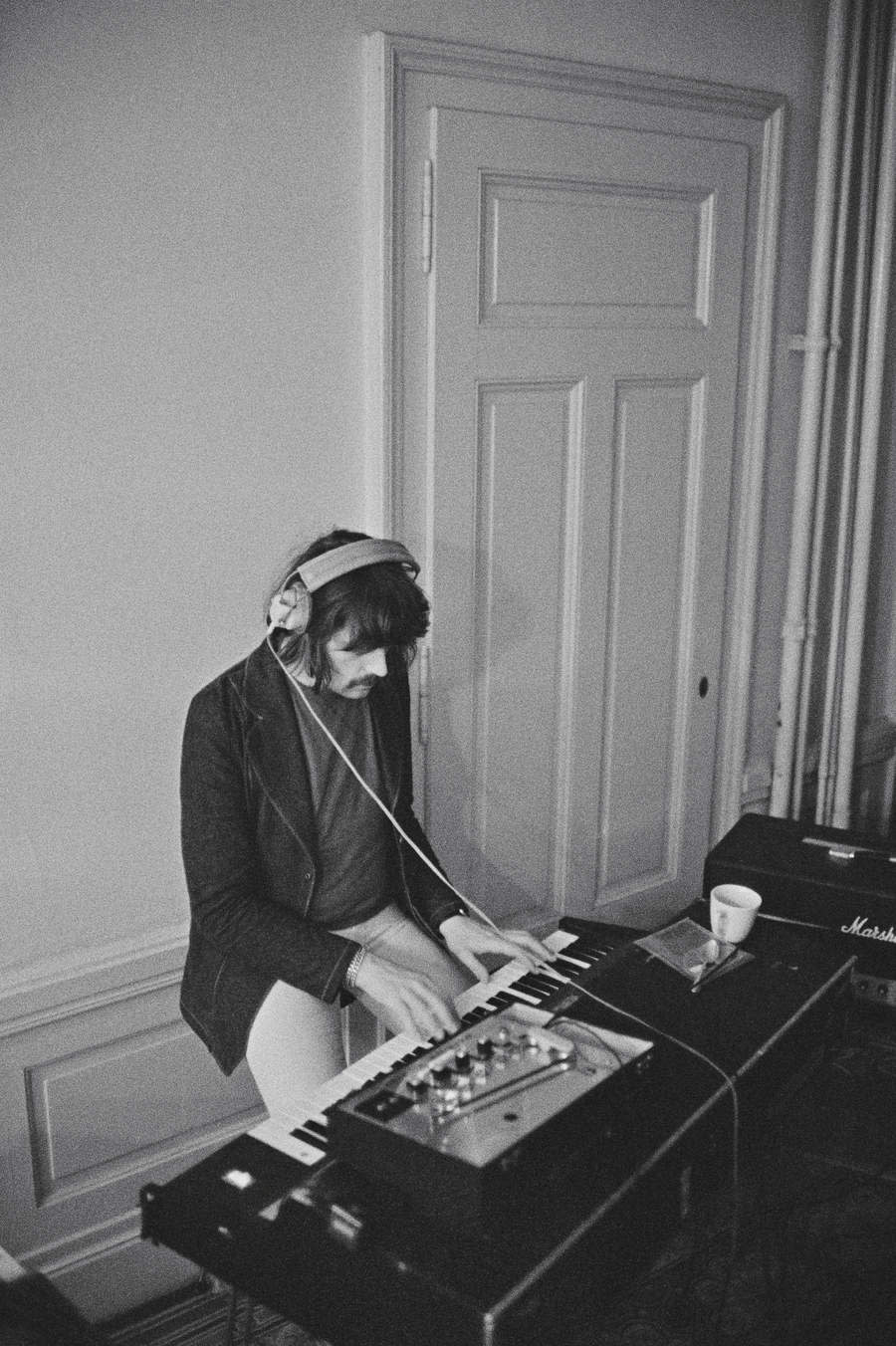

Lord: The Grand Hotel was this forbidding place, this huge great thing – cold, damp, with great ceilings and echoing corridors. I wouldn’t have wanted to stay there in a million years. But we could get it for about thruppence a week.

Blackmore: It was the depths of winter, and we would set up in the corridor of the hotel, Ian Paice in a little alcove with his drums. But every time we wanted to listen to a playback, we would have to leave the corridor and go through two doors into a bedroom, across the bedroom, through another two doors into a bathroom and on to a balcony, run down the balcony, through the French windows into another bedroom, across the bedroom through another two doors on to the landing, and then down a winding staircase to reception and across reception to the front door, and across the courtyard, and then we would get to the mobile. By which time we weren’t too interested in hearing a playback anyway. It was absolutely freezing and the fingers were going numb. Interesting how a couple of days in, it was: “Do you want to hear that one back?” “No, it’s okay, Martin.”

Birch: I think in the end they knew when it was good. And they would ask me, cos I had a talkback into the studio with them. Once they got a song clear in their heads, that was it, we’d start laying it down. And the majority of the time it was one, two, three takes, something like that. We didn’t do any overdubs on the backing tracks. Everything was done live.

Lord: Old mattresses, blankets, we stuffed everything down this corridor and made it as dead a recording environment as possible so that Martin could record it absolutely flat. And if you listen to Machine Head with that in mind, you’ll hear it’s a very dark album. After Ritchie left in 1993, Joe Satriani filled in for us for six months. And he said: “I tell you what, man, that’s the darkest rock album.”

Glover: Highway Star is the opening track on the album. Ritchie is the driving force behind this. He plays with such precision – that driving, machine-gun effect. I came up with the title and a couple of lines. Most of he song is Gillan’s, and everyone joined in on the arrangement. The thing that really impressed me when I first heard it again after so many years was Paicey is swinging – and we’re all playing straight. And that’s the essence of rock’n’roll.

Blackmore: Most of my solos were very spontaneous, except for Highway Star. Probably the one time I ever worked out a solo. I’ve heard other guitar players talk about that solo, but it’s an average guitar solo. It just has identity, and maybe that’s what people relate to.

Glover: On Maybe I’m A Leo, it wasn’t a conscious thought, but I’d just heard How Do You Sleep? by John Lennon, and what I really liked about it was that the riff came in not on the down beat. And I thought I want to write a riff that instead of going ‘two, three, four, riff’, went ‘two, three, four, badam, badam, bom!’

Blackmore: I really like Pictures Of Home, because it is very melodic. There were some members of the band that didn’t like that one at all.

Gillan: I remember writing Pictures Of Home with Ritchie at his house near the airport, near Heathrow. I went round there and his wife Babs was standing there looking Rubenesque, and their dog was doing back somersaults. And we walked upstairs to where he had his guitars. And he had this riff which was based on [Chris Farlowe’s cover of the Rolling Stones’] Out Of Time.

Blackmore: I heard the riff for that on a shortwave radio, and it was probably coming from Bulgaria or Turkey, or somewhere like that. One of these days, these Bulgarian/Turkish people are going to come out the woodwork, saying: “I wrote that.”

Gillan: He told me that it was from a song called Out Of Time. But of course he does get Bulgarian radio signals coming through his head quite a lot, so that would explain that other part.

Blackmore: I remember the rest of the band were a little worried about Ian singing about eagles and snow. I never listen to lyrics anyway, unless it’s Bob Dylan singing. So I said: “Well, eagles and snow. Sounds good enough to me, carry on.”

Glover: We invested an enormous amount of time and trouble into Never Before, because we thought it was going to be a single; it was a bit more commercial. Paice: We thought we should have one track which was radio-friendly. But you can’t get them all right.

Lord: I think Never Before is one of the least popular tracks on Machine Head. But try and imagine Never Before with [Free/Bad Company vocalist] Paul Rodgers wailing away on the blue notes, and I think you’ll arrive at what Ritchie was expecting to hear. What Ian Gillan did was this strange hybrid between a slight pop tune and a very hard delivery, which was what Gillan was astonishingly good at coming up with.

Gillan: I vowed I’d never talk again about that song. It was done for the wrong reasons.

Blackmore: I think we were more excited about Never Before than anything on the record. It’s got this great, memorable little hook. And it failed miserably.

Paice: The crime to me was that the ballad, When A Blind Man Cries wasn’t on the album [it was the B-side of the single Never Before]. It was from the same sessions, it had the same lyricism to it, but Ritchie – he no like it! It would have been a massive song now, had it been on that record.

Lord: The difficulty with that song, but what in fact made it a great track, was using the straight sound on the Hammond, and it pushed me into a way of playing that song which in later years, when we played it live, I never recreated. I never got back to being able to play it that way.I’d given myself a restraint, on purpose, and it shows up strongly on When A Blind Man Cries.

Gillan: Lazy was an instrumental to start with. Then they let me in. So it worked very well, cos the verses were just a blues shuffle. There was this huge, long intro to the song, and you never thought that there was gonna be any words coming to it, but eventually it got there.

Paice: Lazy is one of those that was better a year down the road recorded live, when we got to know it. Sometimes in the studio you just don’t know the piece well enough.

Blackmore: With Space Truckin’, I remember in the early sixties there was a TV series called Batman. And I had this riff that was similar to the theme tune, and I saw how simple that was. I came up with this riff and took it to Ian Gillan and said: “I have this idea and it’s so simple and so silly.” I went over into the corner and played it to him very quietly – I was very shy – and he grasped it immediately, and said: “I think we can use it.” And that turned into Space Truckin’.

Paice: My favourite track rhythmically on Machine Head is Space Truckin’, because of its solidity and simplicity – it’s about the only time Ritchie played block Chuck Berry chords, four to the bar.

Gillan: I recollect the Batman connection. I remember we used to do Batman in [Gillan and Glover’s pre-Deep Purple band] Episode Six, and so Roger would do it all the time, and I think Ritchie sort of improvised around that thing and came up with the beginning of it. But also there was this thing, Keep On Truckin’ [a Robert Crumb comic strip from the 60s].

Paice: So the trucking thing was sort of very in vogue then. It was like, you know, grooving along the street – keep on trucking.

Gillan: We thought it was so modern to be living in the space age. So the idea of being a space trucker, as opposed to a road trucker, was interesting. So you could bring in all these wordsmith tricks and puns and stuff like: ‘They’ve rocked around the Milky Way… They got music in their solar system… We had a lot of luck on Venus… We always had a ball on Mars…’

Lord: We’d walked away from Smoke On The Water going: “This is a cool track but I don’t quite know what we can do with it.”

Gillan: It was just another riff, like Into The Fire. We didn’t make a big deal out of it, and it wasn’t being considered as a track for the album. It was a jam at the first sound-check. We didn’t work on the arrangement – it was a jam. Smoke… only made it onto the album as a filler track because we were short of time. On vinyl, thirty-eight minutes – nineteen minutes per side – was the optimum time if you wanted good quality, and we were about seven minutes short with one day to go. So we dug out the jam and put vocals to it.

Nobs: One night, they rang, and came with a Philips cassette and said: “We just had a friend do a little thing for you which will not be on the album.” They put the cassette on my player, and it was Smoke On The Water. And I said: “What? It’s incredible!” And they said: “You think so? We should put it on the album?” I said: “It has to be on the album!”

Lord: I think it was Joe Smith at Warner Brothers in America who recognised Smoke On The Water as a potential single. We all thought Never Before was the obvious single. It shows how much bands know about commercial consideration. He said: “That’s the single.” And we said: “Are you out of your mind?” He said: “No, that’s the one.”

Glover: With Machine Head none of us predicted [the success of] Smoke On The Water. That was the last thing on our minds that that would become an iconic song. You never can tell, it’s down to the people.

Paice: There is no logic to it. You create everything with the same intention of making it as good as you can make it, and every now and again the public goes: “I really like that one”, and you just say: “Thank you!”

Blackmore: We made Machine Head in three weeks and three days, I think. It was very productive, very constructive, and it had some really good songs. It captured what we were about at the time. Machine Head came out, and it was a reasonable hit. But it wasn’t until Made In Japan [live album, released in December 1972], when we did those songs on stage, that people actually absorbed it and registered that it was a good record. I was surprised, because I preferred the recorded versions.

Paice: The most important thing Machine Head did was to introduce Deep Purple to the USA, because In Rock didn’t come out there.

Glover: Deep Purple to me was two elements: the superb musicianship of Ritchie, Jon and Ian Paice, and the sort of naive, homemade, simple quality of the songwriting that Ian Gillan and I brought to the band. If you get a band of superb musicians, it’s very rarely successful commercially. If you’ve got a band of simple musicians, it can be successful. But what Purple had was both in equal measure. It had this finesse and it had this animal. And to me, that’s what sums up Deep Purple.

Deep Purple and Martin Birch interview material taken from the transcripts for Classic Albums: Deep Purple – The Making Of Machine Head (Eagle Rock DVD, 2002). Additional interviews: Mark Blake, Drew Thompson, Henry Yates, Matt Frost, James Hanley.