The Love Fractures You

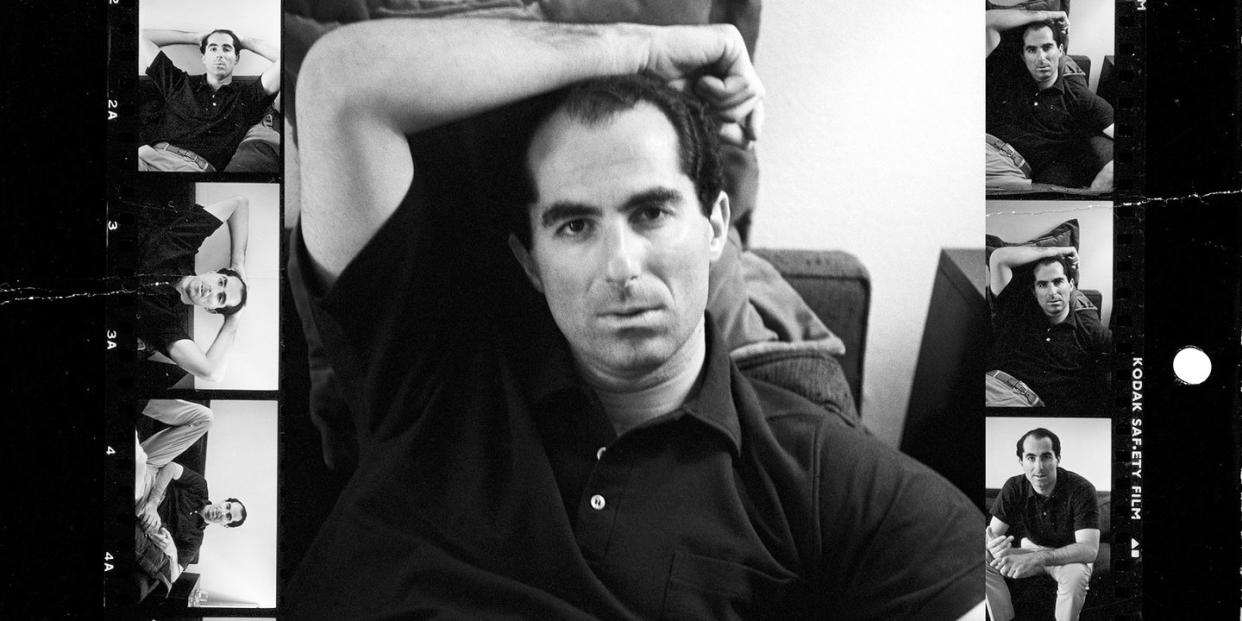

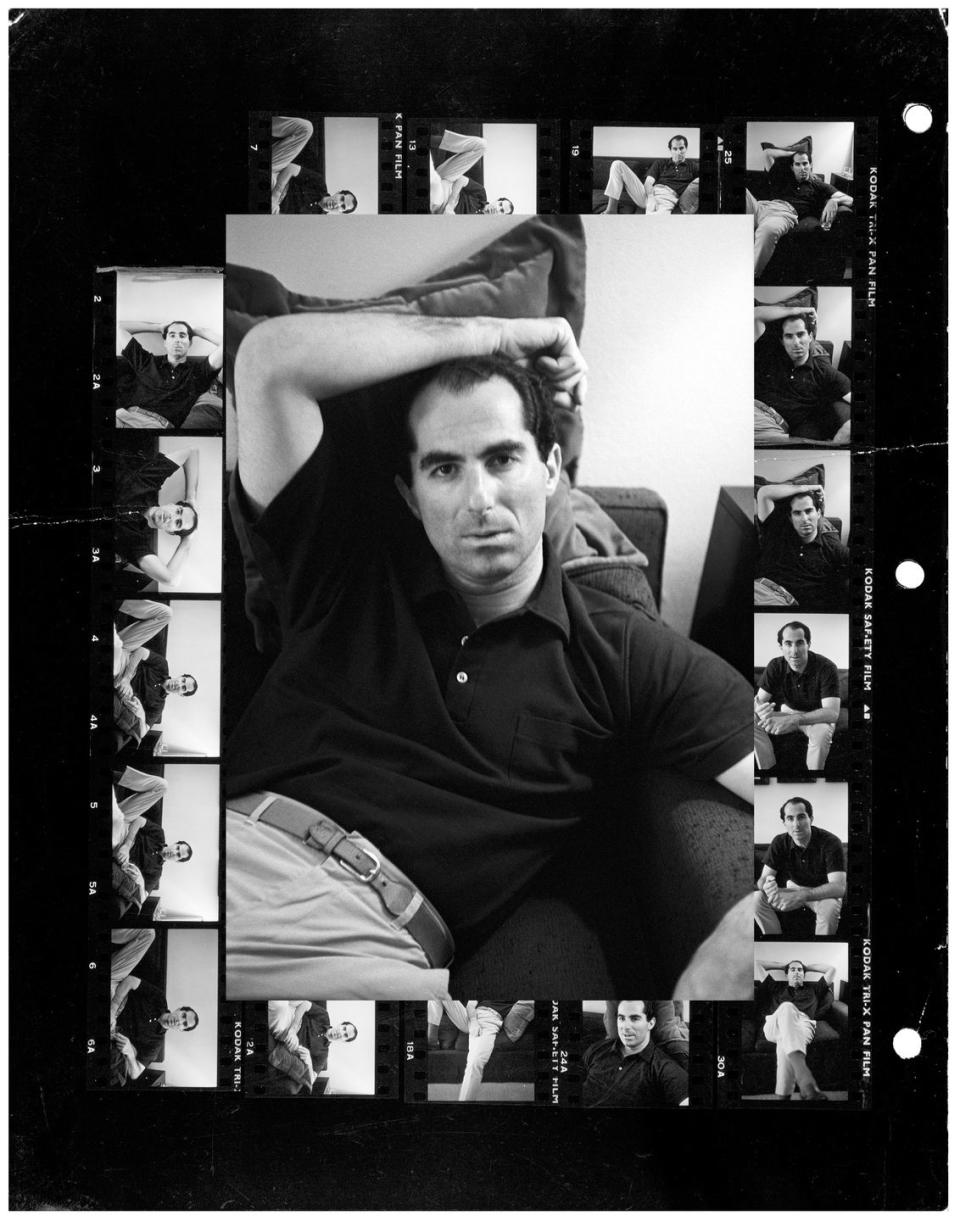

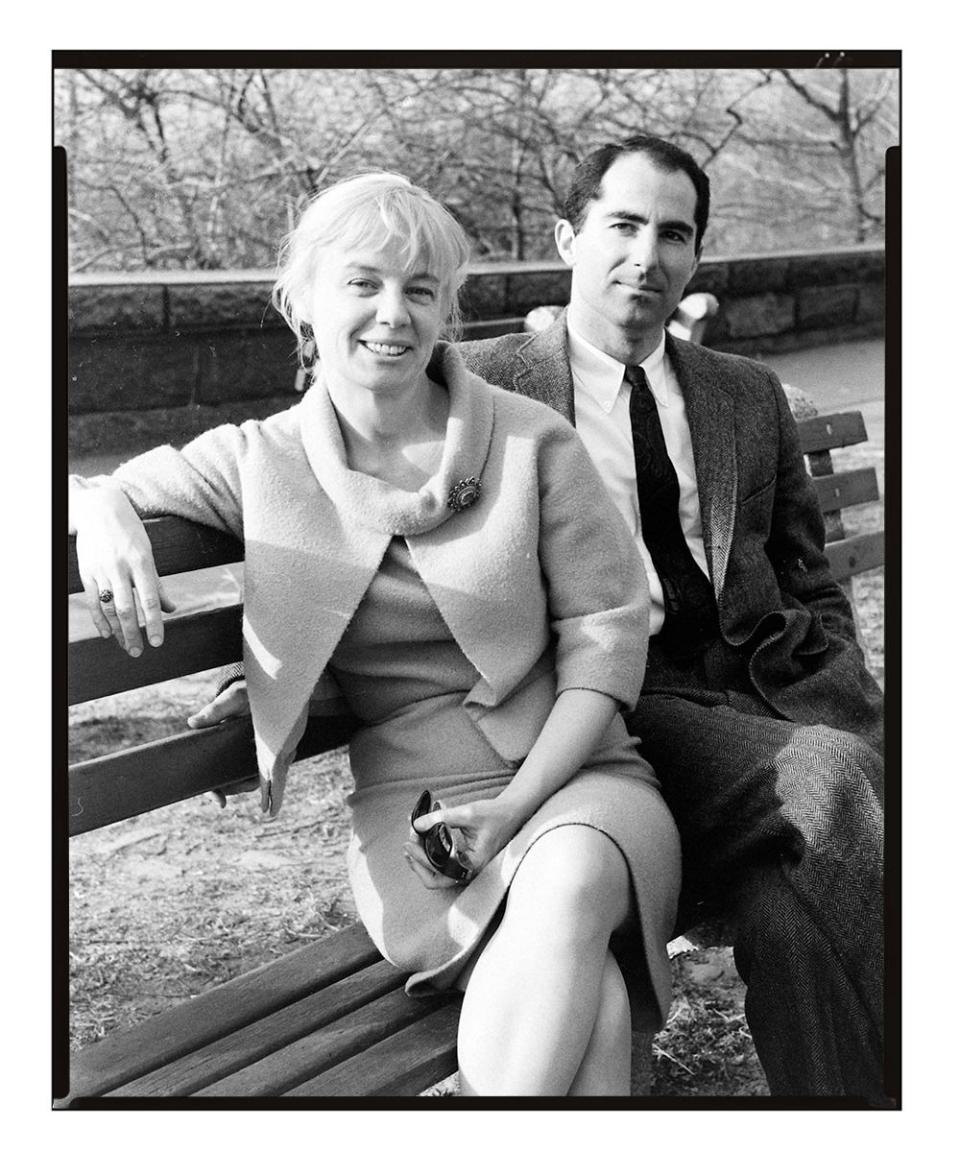

Philip Roth’s first marriage was a disaster. In 1956, as a twenty-three-year-old instructor at the University of Chicago, Roth had met Maggie Martinson, a campus secretary who was almost five years his senior and had two children from a previous marriage. Two and a half years into their chaotic, on-again, off-again relationship, Roth tried to end things once and for all; at the time, his first book, Goodbye, Columbus, was about to be published, which would lead to his becoming the youngest-ever winner of the National Book Award, at age twenty--six. In desperation, Maggie lied that she was pregnant, and when Roth asked her to get a rabbit test, she found an obviously pregnant woman in Tompkins Square Park and paid her two or three dollars for a jar of urine. Almost three years later—as recounted in the excerpt here—the couple were married and living with Maggie’s troubled eleven-year-old daughter, Helen (a pseudonym), in Iowa City, where Roth taught at the Writers’ Workshop and struggled to finish his first full-length novel, Letting Go.

The Roths moved to another rental house in Iowa City, and Philip got a more vivid sense of the challenges posed by his stepdaughter. The night before Helen’s first day of school, he went to kiss her goodnight and remind her to set her alarm clock, and the girl diffidently informed him that she couldn’t tell time. He already knew she couldn’t read, add, or subtract. “She was drowning,” he said. “I thought it was my job to save her . . . . She was so sweet, so willing, she’d been so fucked over.” It didn’t help that Maggie was ashamed of her daughter’s incompetence and would berate her whenever they sat at a table trying to do homework. (“The last thing a kid needs who is struggling with reading and writing,” said Helen in 2013, “is having a parent disappointed and pissed at them.”) Maggie was pleased, however, when she learned that her daughter had a very high IQ (“Your IQ is higher than Philip’s!” she announced), and Roth in turn proudly wrote friends about the girl’s “whopping IQ” despite what he’d previously reported of her illiteracy. Because Maggie wasn’t up to it, Roth took over the job of helping Helen with homework after dinner and would also read bedtime stories with her. “He did take on the task of teaching me how to read, and he was incredibly patient,” said Helen, still emotional about things in late middle age. As a girl she’d particularly loved a book of Russian fairy tales that she and Roth read many times (“with a blue cover, and a bird on this cover”); after every sentence Roth would pause and help her break it down. “Each little pebble of success that I had,” she said, “warmed me to him and he to me.”

Testifying in an affidavit for the couple’s eventual divorce proceedings, Maggie observed, “It was my husband’s opinion that the child was mental retarded [sic], and he wanted to put her in a special school when we came East. I resisted this proposal, however, and Helen was sent to a reading clinic five days a week as well as to the public school. She has improved greatly and many of our friends were astonished that Philip was so ready to see her as a moron.” Howard Stein, however, one of their closest friends, claimed that Roth “was very devoted to that youngster, and he wanted to help her like crazy. It was terribly painful for him . . . . And her mother wasn’t too responsive.” After that first semester, Roth reported to friends that Helen had been attending the Reading Clinic—a program connected with the university’s School of Education—for an hour each day before school, and “now likes to read books—amazing!” Later, Helen would agree the program had been “a godsend,” and pointed out that Roth, not her mother (“Maggie would not do it,” Stein affirmed), was the one who got up at five-thirty every morning to drive her.

Quite apart from what he figured to be his duty, Roth enjoyed the girl’s company. As she began to overcome her shyness, she smiled and laughed easily and was a genial companion to his friends and their children. Not only would Roth take her to school in the morning but he also liked meeting her afterward and walking her home, and it was he who took her trick-or--treating and even drove her friends home from Brownie meetings and so forth. “I began to thrive,” she said, on “finding out what it was to have a good father.” Next to her bed was a tchotchke shelf with little animal toys and other treasures Roth had given her every so often (“Pick a hand”), and soon the girl felt secure enough to tell him she loved him. “[Helen’s] presence has really taught the two of us (Maggie and I) so much,” Roth wrote friends, “that I could go on for fifty pages about it—maybe someday I will.” Maggie, in her journal, recorded that her daughter was “getting prettier by the moment,” and Maggie also noticed the easy affection between her husband and Helen—the way they snuggled in a chair while reading, or held hands while walking together. “Driving back alone with me from the beach one hot afternoon,” Roth remembered in 2014, “squeezed up against me in her wet bathing suit after the two of us had rolled for several hours through the heavy surf with [Helen] safely clutched to my chest, she lifted her child’s face like a little leaf all juiced up on photosynthesis. ‘Kiss me, Philip,’ she said, ‘the way you kiss Mother.’ ” Unlike Swede Levov in American Pastoral, Roth did not oblige her, and he would have been wise, too, not to mention the episode to his wife. One day he and Helen spent a raucous afternoon raking leaves and singing nonsense songs (“oh Lydia, oh Lydia, my encyclopydia, oh Lydia the tattooed lady”) while Maggie watched balefully from the kitchen; later, after Helen had gone to bed, she turned on Roth: “If you ever fuck my daughter,” she snarled, “I’ll drive a knife right down into your heart.”

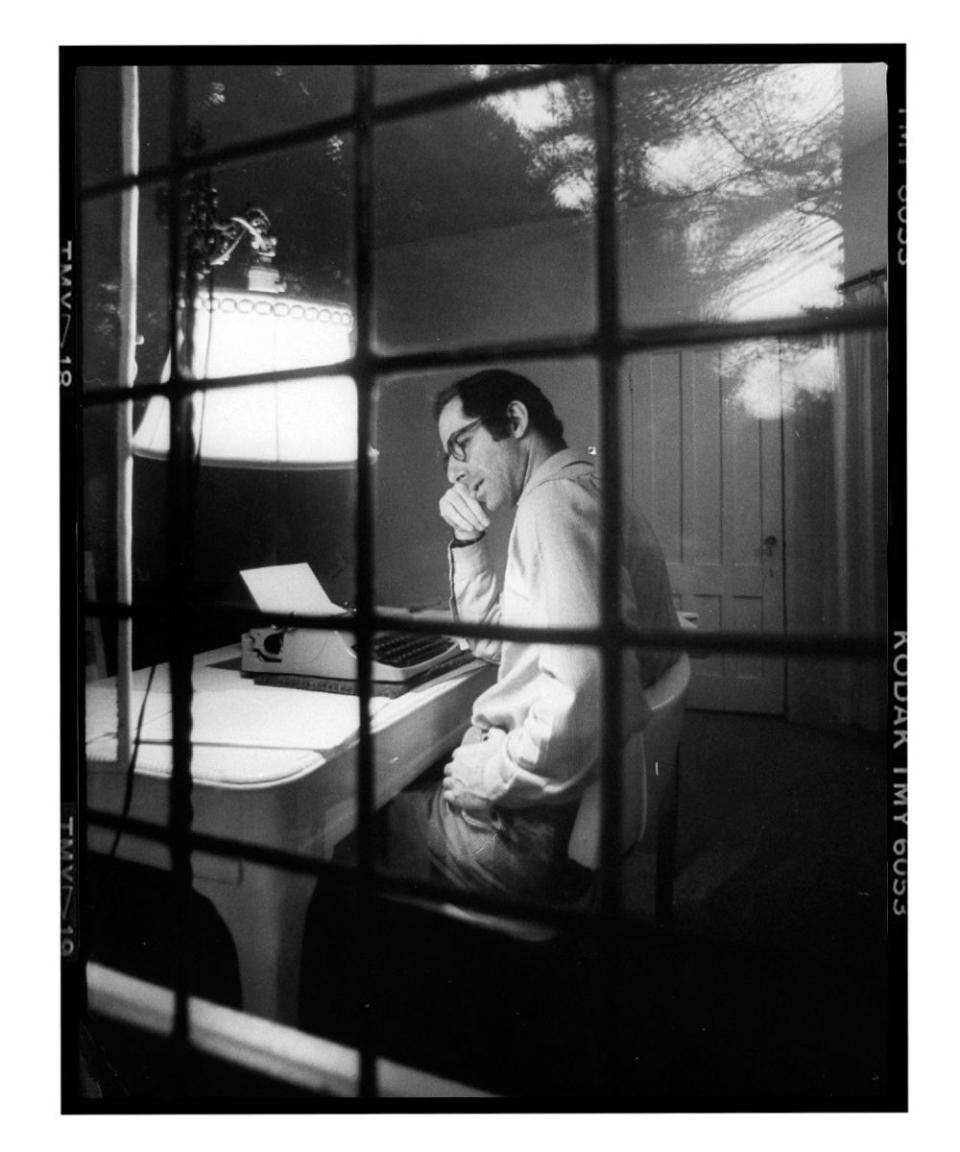

Given his fraught homelife, Roth would always be a little amazed that he’d managed to write Letting Go, a long (950 pages in typescript) novel of which he remained more or less unashamed. “I had managed to write a full-length novel full of strongly drawn portraits of men and women, told from multiple perspectives, and grounded in serious moral themes,” he retrospectively assessed. “I had set out to demonstrate my maturity as a writer.” On October 8, 1961, Roth announced that the book was finished after two years and two months of almost incessant labor—then immediately began to panic (“sure I’d never put down another word again”) and returned to the manuscript for another two months, rewriting an ending that Random House had considered a little too bleak. Finally, when that was done, he wrote the story about injuring his back in the Army, “Novotny’s Pain,” and promptly sold it to The New Yorker.

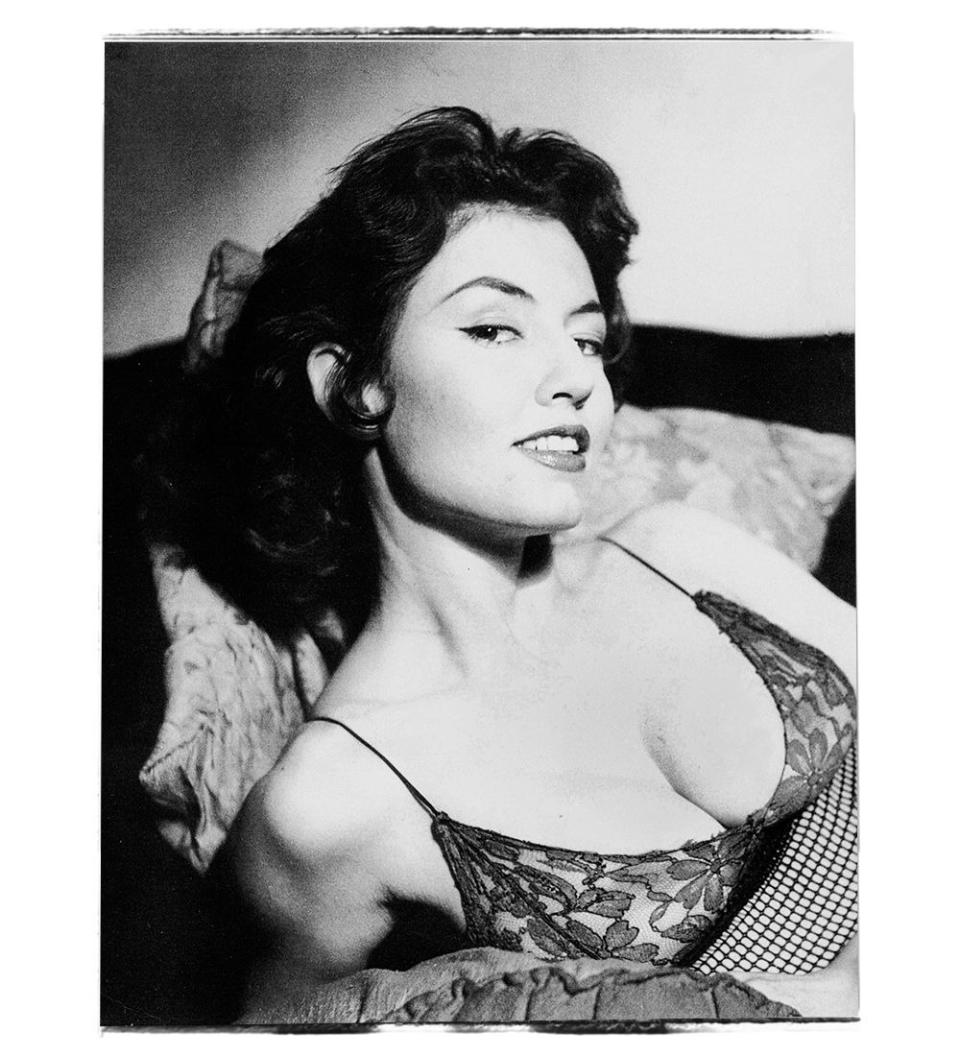

“Philip is such a seer,” Maggie wrote in her journal on December 28, noting this latest triumph. “I suppose this is a sort of pinnacle in our lives for everything P. does seems to succeed and we’re making more and more money and even getting happier I think. I seem to feel happier with him and he behaves as though he’s happy too. I’m always melancholy though, it’s in the blood.” Roth was only too aware of his wife’s melancholia and its various harrowing forms, but he was about to embark on a “gala week” in the East and was feeling his oats, all the more given that Maggie, for once, had to stay home and care for her daughter. Amid delivering lectures at Princeton and NYU, and dropping his novel off at Random House, Roth ran into a former Playboy Playmate, Alice Denham, whom he’d met once at a literary party (Maggie in tow). This time he promptly arranged a tryst at her apartment the next day, and, after a long afternoon of sex, mentioned he’d be in town for another week and would certainly call again. On sober second thought, however, he decided to leave well enough alone.

Alice Denham (Miss July of 1956) enjoyed the distinction of being the only Playmate ever to publish a story in the same issue as her centerfold, and her roster of sexual conquests—Norman Mailer, William Styron, Nelson Algren, Joseph Heller, William Gaddis, et al.—is a veritable who’s who of postwar literature. When she later published a memoir about this aspect of her career, Sleeping with Bad Boys, Roth couldn’t bear to read it “for fear of how [he] measured up (or down) in bed against these drunken literary mastodons.” But he needn’t have worried: “Philip Roth was a sex fiend,” she wrote. “He moved from tits to—aaaah!—so fast I was breathless. Speeded up like his talk and his head. But once he got there, he hung in long and steamy. Tepid men never move me. Philip was on fire.”

Meanwhile, at Princeton, Roth met the head of the writing program, R. P. Blackmur, who subsequently offered him a job as a writer in residence for the 1962–63 academic year. He also met his new celebrity publisher, Bennett Cerf, a regular panelist on TV’s What’s My Line? Finally, Roth bought sweaters for Maggie and Helen before returning to Iowa City.

About two weeks later, on a sunny snow-laden day, Roth came home from campus after lunch to find his wife waiting for him in a rage. “You son of a bitch! You filthy cheating dog! You’re worse than my fucking father!” When she paused for breath, Roth asked what it was all about, whereupon she showed him a card (later Exhibit A in Roth v. Roth) that she’d opened from Alice Denham, on which was printed a Dürer woodcut of a man leading away a downcast woman (caption: “The twelve months have gone. Come on, Gredt, we’ll start again”); Denham’s note was brief: “Chicken! / —Alice.” In 1966, Roth wrote a friend that Maggie’s grand remonstrance went on “for three days running,” an ineffable ordeal that he would later abridge to a mere ten or fifteen minutes—until, that is, he’d “had it with the fucking assault, which was at the same pitch of crazy intensity whether I’d said the wrong thing to the waiter at the restaurant or stuck up a bank.” Yes, he confessed, yes, he had indeed fucked Alice Denham in New York; then he went upstairs, packed his toilet articles and some underwear, announced “I’ve had enough of you,” and walked out the door.

He’d gone maybe two or three blocks when it occurred to him that Maggie would try to kill herself and Helen would come home from school and find her mother’s body. Sure enough, when he returned, she was sitting on the floor in her underwear; a whiskey bottle and empty pill vials were nearby. “I’m going to die,” she said. “I want to tell you something.” Roth dragged her to her feet and upstairs to a bathroom, where he put his finger down her throat and made her throw up. Then he put her in bed. “I’m going to die,” she repeated, and proceeded to tell him that she hadn’t really been pregnant just before their marriage; she described her transaction with the pregnant Black woman in Tompkins Square Park, and so on. “I was completely stunned on learning of her deception,” Roth observed in his own affidavit for the divorce case. “Our marriage had been three years of constant nagging and irritation, and now I learned that the marriage itself had been based on a grotesque lie.” Roth sat in the corner of the bedroom, calmly taking it in; a two-word phrase he sometimes liked to tell himself (“when confronted by great surprises of an unhappy nature”) seemed to apply: “This, too.”

Roth phoned his friend Bob Williams and asked him to pick up Helen from school and give her dinner. Then he returned to his chair in the bedroom. Soon Maggie fell asleep, and didn’t die. At last he retrieved Helen and gave some excuse to the Williamses for the snafu. “I couldn’t tell anyone,” he remembered, “—it was all too lurid.”

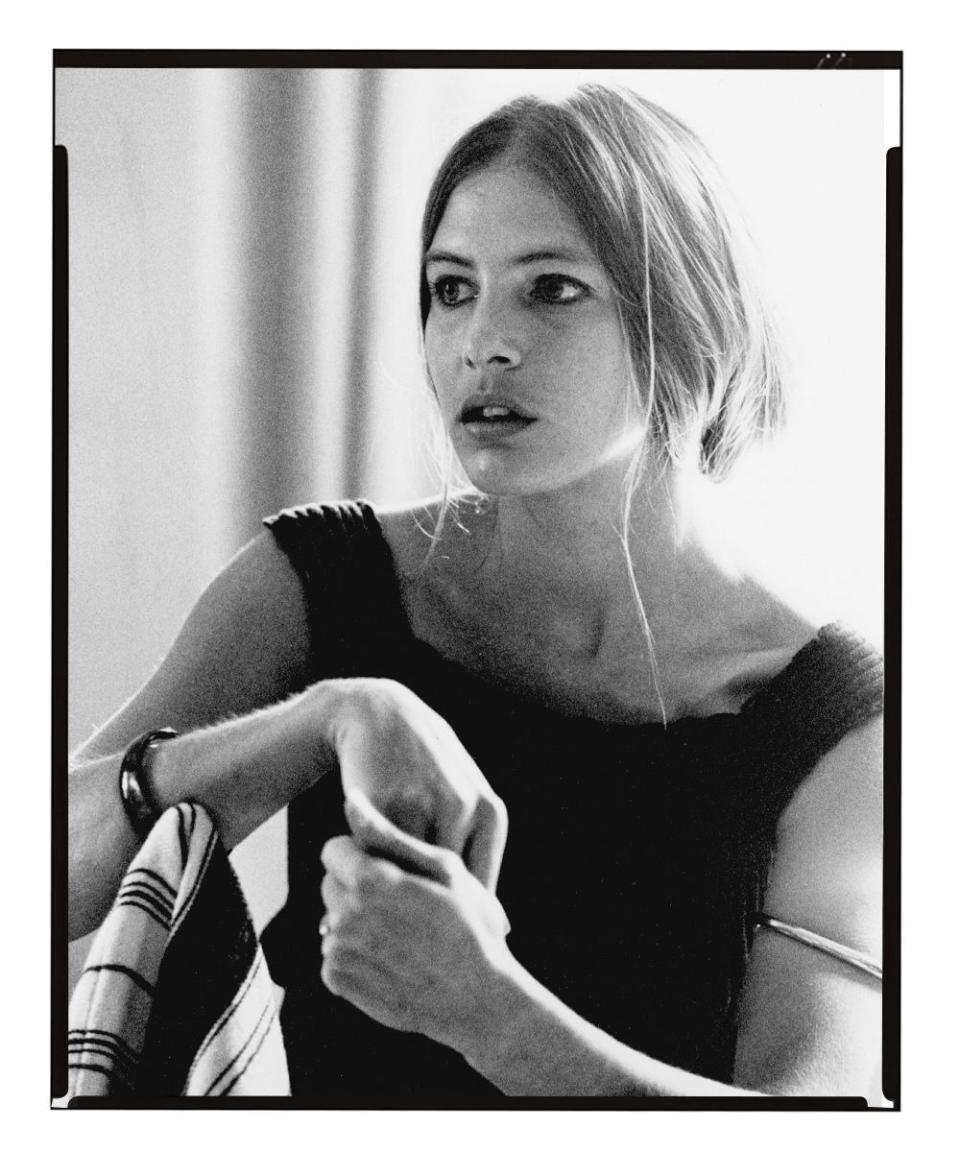

That spring Maggie and he slept in separate bedrooms, and Roth began having an affair with one of his students—an attractive, talented twenty-two-year-old, Lucy Warner. The young woman had caught Roth’s eye before, but in light of Maggie’s revelation he gave himself permission to pursue her. Lucy was an undergraduate who’d been promoted to Roth’s graduate workshop that spring because, as she recalled, one of her stories had been accepted by The Atlantic. Like Roth, she was rather at emotional loose ends. The previous year she’d eloped, disastrously, with another writer at the workshop, and spent the rest of that school year as well as the fall semester in New York, disentangling herself. Both she and Roth vaguely remember his writing “See me after class” at the top of one of her papers; then he took her for a wary walk or for coffee (“He was very terrified of being seen together”) that eventuated, either that day or soon after, in their sleeping together at Warner’s apartment.

Roth was in love. Amid the tense atmosphere at home, he’d sometimes spring to his feet and announce he was taking a walk, then flee across the river and up a long hill to Warner’s second-floor apartment on East Burlington, where he’d skittishly hang sheets over the windows (no curtains) before getting into bed: “Cheever used to swim across Westchester County,” he said; “I used to run across Iowa City.” Roth’s feelings were mostly reciprocated; Warner’s friends at Iowa had been her short-lived husband’s friends, and now she was alone. She remembered the young Roth as “skinny and nervous and funny” and of course “very smart” (the only person with whom she could ever discuss Italo Svevo): “I didn’t feel any rough edges,” she said. “I did later, but not then.” Though he was careful not to burden her with any but the most salient grotesqueries about his marriage, she saw how desperate he was and liked the idea of giving him a haven. “I was always so overjoyed to see him, and felt kind of cherished.”

By then Roth had arranged to rent a house in Princeton the following year for Maggie, Helen, and himself, and had also rented a summer place in Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, near some Iowa friends, the painter Jim Lechay and his wife, Rose. That spring, however, he decided he couldn’t live without Lucy Warner. On her desk was a picture of her family home on an island in Maine, and thither Roth hoped to escape with her, sending Maggie to Wellfleet alone. Then he would devote the summer to getting out of his nightmare marriage and starting over.

Looking back, Lucy Warner found it hard to believe that she’d ever seriously considered Roth’s proposal to run away to her family house in Maine. Her mother was there, for one thing, and the woman had taken a very dim view of Lucy’s hasty marriage and divorce the year before. Still, despite an almost abject wish to regain her mother’s approval, Warner might have run away with Roth to somewhere if he hadn’t expressed a curious concern about becoming too attracted to his stepdaughter as “she got a little older.” “That was an alarm bell for me,” Warner remembered.

Roth was devastated when she told him, toward the end of May, that she couldn’t go to Maine (or wherever) with him after all. In her affidavit the following year, Maggie would claim that their separation around this time had been temporary—he’d planned to rejoin her later that summer on Cape Cod—and attributed their problems to “his emotional state prior to the publication of Letting Go.” This, of course, was a distortion, but plausible up to a point. “Phil, I know you are going through a bad time now,” his editor, Joe Fox, had written him on April 24. “I don’t need to tell you that every author goes through this torture in the month or two months before publication; you know that anyway and it doesn’t help.” Fox quipped that he should work on his backhand and “listen closely to whatever Maggie says,” but of course Roth could hardly bear the thought of his wife, still less now that Lucy was fading from the picture. “He snarls and glowers,” Maggie wrote in her journal. “I ‘drive him crazy.’ It seems hopeless.”

As the summer holiday began, they put Helen on a train to Chicago without discussing the separation with her; Maggie figured they’d be reunited in time for Helen’s arrival in Wellfleet on July 19, but for now Roth was staying in Iowa while Maggie drove east on June 7. Alone in the big rental house on Cape Cod, she puzzled over their estrangement in her journal. Though not imperceptive in other respects, she seemed blind to the main cause of her husband’s dark mood: “[Philip] understands and discerns so much and really feels so little . . . . I never feel really really loved, only ‘given to,’ and I’m never allowed to love Philip in the emotional, physical way that I feel most naturally. It’s quite terrible. Somehow [italics added] Philip has a deep hostile feeling for me and when face to face the emotion I sense is hatred.” Meanwhile, Bob Baker was startled by the news that his friends’ marriage was effectively over (“I don’t see that I can go back to Maggie,” Roth wrote him on June 9, “without, finally, our really destroying one another”); so fond were Bob and his wife, Ida, of the Roths—Maggie too—that they’d named their second and third children Philip and Margaret. Their primary loyalty was to Philip, however, and they urged him to come to their home in Oregon and stay as long as he liked, the way he’d almost done three years ago, when he considered fleeing Maggie rather than marrying her.

In the end, though, he couldn’t bring himself to board the airplane in Cedar Rapids. His fear of flying flared up amid general anxiety, and he phoned his brother instead and asked if he could stay awhile in his Manhattan apartment, located in Stuyvesant Town; Sandy told him to come ahead—his wife, Trudy, and their two boys were summering on Fire Island, so Philip would have the place to himself much of the time. Finally he made his excuses to Bob Baker, who didn’t like the way his friend sounded. “The black fact is that we are concerned about his mental health,” Baker wrote their mutual friend, Ted Solotaroff, afterward, begging him to keep an eye on Roth in New York and let them know how he was doing. “We love the big lug and this is pretty important to us . . . . We haven’t had anyone to turn to for information and—as you’ll understand—we haven’t wanted to press Phil.”

The train trip to New York was an unpromising start to single life, as Roth stopped at a newsstand in Chicago to read the first major reviews of Letting Go in Time and Newsweek. He remembered staggering back to a bench as the words sank in. Two months before, he’d noted his growing dread that the novel to which he’d given so much would be dismissed as “a sad book,” among other things, and here it was in black and white. “Melancholy Journey” was the title of the Newsweek review, whose author described Roth’s hero, Gabe Wallach, as “a selfish, irresolute kvetch,” and likened Roth’s “carefully brilliant set-pieces” to “gaudy depots on the Trans-Siberian Railway.” The Time review (“The Grey Plague”) was a little more sympathetic, suggesting that writers should “solve the second-book problem the way architects solve the 13th-floor problem”—that is, by skipping from the first book to the third.

Sandy was getting ready for a party when Philip arrived that evening; noticing his brother’s frayed nerves, Sandy gave him a phone number where he could be reached. Philip had taken a shower and made a sandwich when the phone rang: Maggie. Though he hadn’t told her his whereabouts, she’d speculated in her journal that he wouldn’t be able to board a plane to Oregon (a likely destination, as she well knew), and hence she was “betting on New York” where, she wrote, he could “see people and talk about his book.” She moreover recorded the fact that she was very drunk by the time she finally got hold of the fugitive. Shouting, she told him that if he didn’t stop this nonsense and come to Wellfleet she’d ruin his life, soaking him for alimony and denouncing him as a cheating philanderer to whosoever would listen. Afterward, Roth tried calming himself with a walk, but when he returned to the apartment he began to shake and was wracked by fits of vomiting and diarrhea; finally he phoned Sandy, who came home immediately. That night Philip belatedly told his brother the whole lurid saga—from the urine ruse to the suicide-attempt-cum-confession back in January.

About a week after his arrival in New York, Roth visited William and Rose Styron at their home in Roxbury, Connecticut, in rustic Litchfield County. Roth informed the couple of his separation from Maggie and asked if he could rent Bill’s two-room studio while they spent the summer, as ever, on Martha’s Vineyard; they insisted he take the studio for free, and even let him use an extra car. Roth had never lived in the countryside and was enchanted by the nearby swimming pond, the long vistas of farmland and wooded ridges, the little general store, and even a famous playwright, Arthur Miller, who stopped by with his wife, Inge Morath, to introduce themselves at the Styrons’ urging.

By then Lucy Warner had also returned to the East and was visiting her brother in Newport, Rhode Island, where he was stationed with the Navy—this after an unhappy meeting with Roth at his brother’s apartment in New York, the day after the drunken Maggie had threatened to leave him as destitute as his friend Marty Greenberg, who was also going through a brutal divorce. Hardly a model of solidity herself at the time, Warner was spooked by his panicky behavior and bolted on the pretext of having a doctor’s appointment. A couple of weeks later Roth phoned her from Connecticut and, wishing to make amends, she agreed to take a bus to nearby Southbury. For a few days they had a pleasant visit, going on long walks and sleeping together, until one night Maggie called while they were broiling steaks. For the next hour or more, Roth and his wife yelled at each other with mounting hysteria while Warner waited outside and the steaks turned to shoe leather. The next day she left for Maine, though not before saying, à la Karen Oakes in Roth’s autobiographical novel My Life as a Man, “I can’t save you, Philip. I’m only twenty-two years old.”

A version of this article appears in the April / May 2021 issue of Esquire.

Adapted from Philip Roth: The Biography, by Blake Bailey, out April 6, 2021, from W. W. Norton & Company Inc. Copyright ? 2021 by Blake Bailey. Copyright ? 2021 by the Estate of Philip Roth.

You Might Also Like