Leonardo DiCaprio’s ‘Flower Moon’ Snub: Why the Oscars Have a Love-Hate Relationship With the Star

Leonardo DiCaprio, once again, missed out on an Oscar nomination.

But that comes as no surprise.

More from Variety

DiCaprio’s portrayal of easily-led naiveté and of greed blotting out love helps to set the tone of last year’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” just as his vexed internal conflict drives “The Departed” forward and his headlong passion launched a million “Titanic” fans.

It’s hard to feel bad for DiCaprio — who, first of all, is among the world’s most famous (and famously high-living) celebrities, and, what’s more, did indeed finally get his trophy. After an aggressive campaign that leaned hard on the notion that he’d been pushed to the edge of safety, and, perhaps, sanity in “The Revenant,” he picked up his award.

And while his derring-do and his survival instincts in that film were indeed a feat, they weren’t what DiCaprio does best. This makes him one of many performers whose Oscar is for work unrepresentative of the rest of their oeuvre, sure. But it also speaks to something greater. The Oscars’ love-hate relationship with DiCaprio — in which so much of his best work, from “The Departed” to “Catch Me If You Can” to “Revolutionary Road,” has gone entirely un-nominated — suggests an industry that’s never quite been at ease with what one of its biggest stars can do.

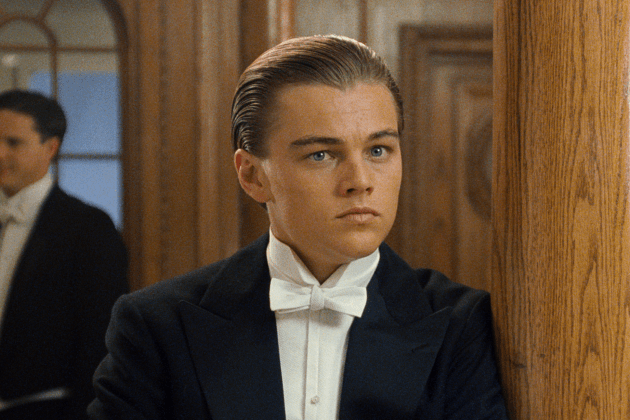

By the time DiCaprio appeared in “Titanic,” he had already been an Oscar nominee for playing an intellectually disabled teenager in 1993’s “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape”; that role was the sort that’s easy to recognize as a standout, and DiCaprio, then, was laden with none of the baggage that would get ported in on the Ship of Dreams. “Titanic” made him an international fixation, a heartthrob with real artistic ambitions of the sort that hadn’t, perhaps, been seen since Beatty, or Valentino. The hysteria around him may have been judged its own reward; when “Titanic” reeled in 14 nominations, DiCaprio’s name wasn’t called, and he skipped the ceremony entirely.

Was DiCaprio worthy of an award for “Titanic”? People have been nominated for less than helping to anchor the romance at the center of the biggest film ever made. And what might have seemed like a “snub” began to blossom into a grudge, with DiCaprio never meaningfully in contention for the next grown-up movies he made, “Catch Me If You Can” and “Gangs of New York,” both released in 2002. What DiCaprio would have to do to catch Oscar’s eye began to glimmer into clarity with 2004’s “The Aviator,” for which he was nominated. In “Titanic” and “Catch Me If You Can,” he’d made a meal out of his personal charm, showing both his suavity and its limits. In “The Aviator,” in which he depicted the downward spiral into madness suffered by real-life magnate Howard Hughes, he was made to suffer.

Which takes nothing away from the performance — a very strong one, in fact, and the one that cemented the collaboration he’d begun with Martin Scorsese on the set of “Gangs of New York” as a real going concern. But what the voters seemed to want from DiCaprio was to see meaningful effort, to watch that pretty face contort with a bit of agony. Just two years later, he sat at the center of “The Departed,” the film that would eventually win best picture, and played out a struggle of divided loyalties and self-sacrifice through a chewy Boston accent. His race to talk his way out of each jam with a certain criminal charisma made for movie-star work, the kind that Oscar seems to recognize for many performers but him. DiCaprio’s nomination that year for less substantial work in a less impressive movie, “Blood Diamond,” came as a surprise only until one recalled that in the Edward Zwick thriller, DiCaprio’s Rhodesian accent was even more tactically deployed. Once again, DiCaprio was honored only once he made it clear he was striving for it.

So it went for DiCaprio, once again ignored for a reunion with “Titanic” co-star Kate Winslet in 2008’s “Revolutionary Road,” in which both partners personified plainspoken and unaffected agony within a marriage. (This one may not have just been a DiCaprio thing; Winslet’s nomination, and win, that year, came for playing an illiterate Nazi, perhaps history’s greatest example of being made to show one’s work.) And with “The Wolf of Wall Street” in 2013 — coming a year after a might-have-been-nominated turn as the charismatic evil at the center of Oscar favorite “Django Unchained” — DiCaprio made a three-hour-long heel turn, a depiction of bottomless avarice studded with ingenious physical comedy, look effortless. Which may have been why he lost to Matthew McConaughey, whose physical decline as a rodeo cowboy with AIDS in “Dallas Buyers Club” was rooted in effort one could see scrawled across the screen.

DiCaprio certainly seemed to want an Oscar by the time “The Revenant” came around, and the stars aligned — including a field of competitors that call to mind the season of “Survivor” structured with a cast designed to let fourth-time returnee Rob Mariano walk to a victory. There are plenty of stars who’ve waited for a win, but few whose core characteristics as performers — in this case, a charisma that can easily be turned towards manipulation or chilly amorality — seem to leave the Academy unmoved. (That he ended up nominated for “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” may be explained by some curse finally having been lifted with his winning for playing an uncomplicated secular saint who suffers for our sins in “The Revenant.” Or maybe it’s just that in “Hollywood” he gets a hero’s ending.)

So it is with “Killers of the Flower Moon,” in which DiCaprio puts every bit of himself into playing a character one would never want to meet. Perhaps it really is exhausting rooting for the anti-hero, or even just watching him. DiCaprio’s wiliness in exploiting Lily Gladstone’s (beautifully played, as well) character draws upon his essential gifts, and his ability to conjure his character’s nascent and uncomplicated thoughts as though they’re occurring to him for the first time is a testament to DiCaprio’s ability to draw out the shades of meaning from the elemental, just as he did finding stardom in the “Titanic” screenplay. It’s not a set of skills the Oscars seem to want for a man who got his prize, finally, for fighting bears, even as all fans might have wanted to do was see him use his silver tongue to talk the beast into submission.

Or maybe it’s something else. DiCaprio, after all, was finally given the prize once he went as far as it’s possible to go on a film set, and then told us about it, and told us about it. But this is the same performer who skipped the ceremony when the film he was in had made him the biggest actor on earth, and won best picture; he’s the same performer who’s used each of his glancingly rare media opportunities, this time around, to talk about how special a scene partner Lily Gladstone is. (And Gladstone now appears likely to win best actress.)

DiCaprio’s lifestyle makes headlines, and he’s one of the only actors on earth who could get a film as expensive and not-obviously-commercial as “Killers of the Flower Moon” greenlit. Having won at last, DiCaprio doesn’t seem to need another Oscar, not when he already has it all. And need — that thing that pushes past demonstrations of movie-star charm with big accents or broad suffering, even though movie-star charm is what makes movies work — is at the center of the Oscars. DiCaprio, in the end, will be fine without another prize, and the Oscars, just as they have over the course of his career, seem to recognize that.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.