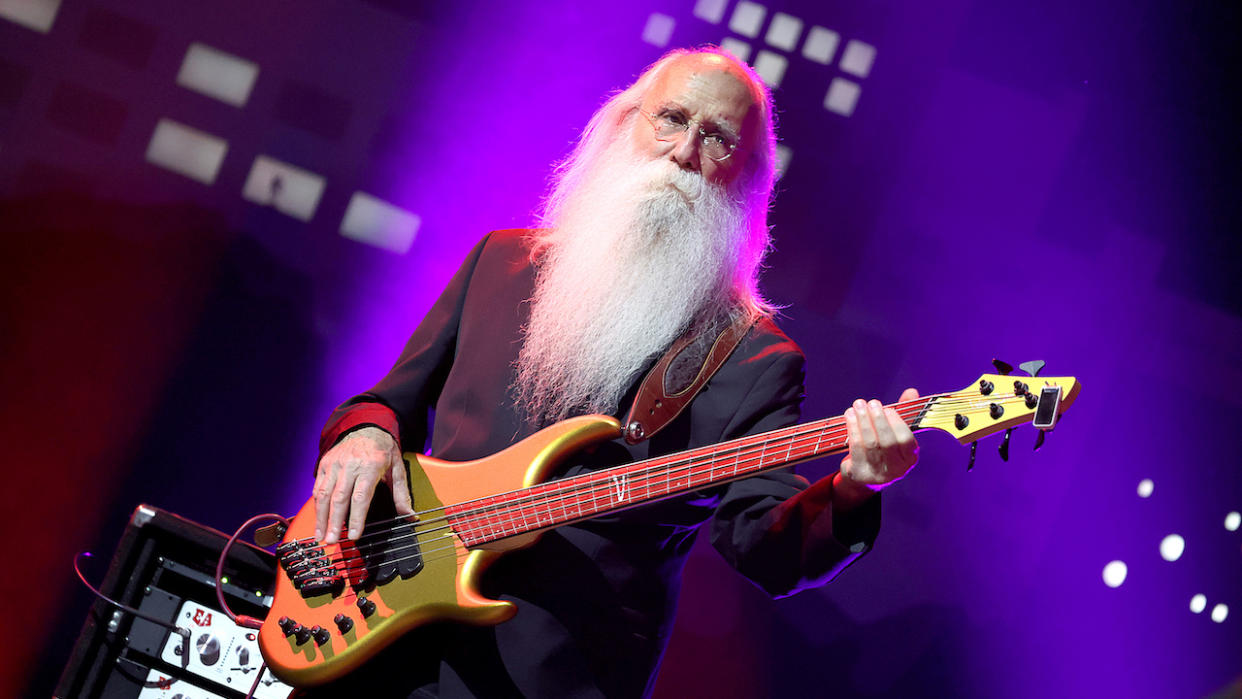

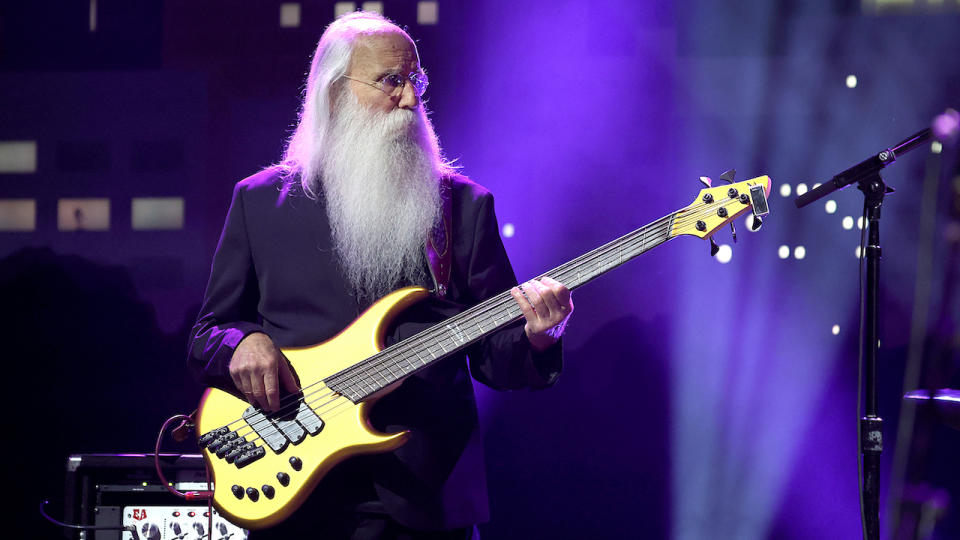

Lee Sklar: “If the drummer doesn’t swing – let him serve French fries in McDonald’s"

Few faces within the bass world are as instantly recognisable as session great Lee Sklar. Aside from being a gun for hire, Lee is probably best known for his longstanding work alongside Phil Collins and James Taylor, but unlike so many bassists, it’s impossible to label the one kind of music that he gets called for. “When I got into the studio scene, I found myself getting all kinds of calls,” Lee told BP. “One minute I’m doing Helen Reddy’s I Am Woman, and the next thing I know I’m doing Spectrum with Billy Cobham. The call’s would come in and I’d look at everything as a challenge.”

After 50 years in the industry, having seen recording technology bloom from the days when a four track was state of the art, how have things changed for Lee? “Firstly, I’m all in favour of technology – I don’t want to be living in the stone age – but with Pro-Tools and such like, you’ve got singers that can’t sing to save their lives and engineers whose whole careers are spent tuning bad singers. You’ve got a drummer with no time, so you move the beat. As far as I’m concerned if the drummer doesn’t swing, fire him – let him serve French fries in McDonald’s, but don’t let him get in a studio.”

“Every once in a while I work on things and I feel like I’m in the old days,” says Lee. “We got so used to that – going into sessions with Jim Gordon or Jim Keltner and the pocket was so strong! Everything was based on ensemble playing, whereas nowadays, at least half the work I do, I’m just overdubbing to sequenced bass and they want it to feel natural, but you’re already handcuffed by the fact that this was done to a sequencer!”

The rise of technology has undoubtedly led to the decline of the traditional recording studio, allowing most modern electronic music to be made with nothing more than a laptop. However, it’s not only the technology that’s changed, but also the method of recording. “They want you to make the track breath a little bit," says Lee. "I often think: ‘why don’t they just put a real rhythm section together?’"

"People want to keep as much control and money as they can, and they are afraid to let a bunch of guys come in and actually play something. I’ve made records that way and suddenly we’ll do a gig and the first time the band plays the song it’s 100 times better than the record and they’re wondering why! It’s because we’re all putting personality into the tunes.”

With such a wealth of experience to draw on, across so many musical genres, how does Lee come up with his bass parts? “The one thing I’ve cultivated is a real sensitivity to singer/songwriters,” he says. “I know how to accompany, and how to listen to a person breathe to hear where the downbeat is – to never try to lead them. I’m really comfortable on that seat.”

“Guys get so used to ‘time’ that they don’t really understand that you can have a beautiful pause before a verse, because you’re human! Don’t do all your training with a metronome, try to understand what it is to really feel a song. Don’t be afraid to leave that kind of space. I often get hired because the artist feels comfortable with the extra room.”

Leland Sklar’s book, Everybody Loves Me, is now available on Amazon.