‘Like kissing Hitler’: The stars who failed Hollywood’s ‘chemistry test’

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re an actress at the beginning of your career. You’ve been acclaimed for your performances on stage – your Ophelia was the talk of the National Theatre, and your Chekhov interpretations have been described as “breathtaking” – and your agents and manager are now keen that you make the leap to cinema.

You’re perfectly comfortable with this, fancying the idea of greater exposure. But it is somewhat to your horror that, after having successfully impressed the director and producer of a new romantic comedy, you’re then wheeled into a room where a succession of considerably older and more famous actors are waiting for you. You are then peremptorily instructed to kiss each of them in front of half-interested prying eyes, in order to see if you click. This, for the uninitated, is the “chemistry test”.

The unpleasant and often humiliating ritual that actors (of both sexes, but predominantly women) have had to undergo for years has always been under the radar, but none other than Anne Hathaway has come forward to discuss its grimness, in a recent interview with V Magazine to promote her new romantic comedy The Idea of You.

To great uproar, she revealed that, during her ingénue days two decades ago, she would be compelled to kiss actors all day. As she put it: “Back in the 2000s – and this did happen to me – it was considered normal to ask an actor to make out with other actors to test for chemistry, which is actually the worst way to do it.”

She hated the experience, saying that “I was told, ‘We have 10 guys coming today and you’re cast. Aren’t you excited to make out with all of them?’ And I thought, ‘Is there something wrong with me?’ because I wasn’t excited. I thought it sounded gross.

“It wasn’t a power play, no one was trying to be awful or hurt me,” she went on. “It was just a very different time and now we know better.” Yet Hathaway remains aware today that had she refused to participate, it could easily have been the end of her mainstream career. As she admitted: “I was so young and terribly aware how easy it was to lose everything by being labelled ‘difficult,’ so I just pretended I was excited and got on with it.”

Hathaway has since gone on to a glittering career that has included everything from Oscar-winning glory in Les Misérables to working with acclaimed directors such as Ang Lee, Nolan and James Gray, and there is a welcome paucity of cookie-cutter Hollywood rom-coms on her CV that have required her to look winsomely at her leading men while kissing them passionately.

Yet what her comments have done is to reopen discussion about the chemistry test in Hollywood, which used to be standard practice, but, as Hathaway has now suggested, has disappeared. Nowadays, the industry has “intimacy co-ordinators” who carefully monitor the co-ordination of a love scene so that there can be no complaints of exploitation, but in recent memory, the priority was in seeing whether the couples on screen could fall in love with one another convincingly. Some producers and directors were prepared to go to extreme lengths to achieve this.

Admittedly, few went as far as Robert Evans, who Sharon Stone recently recounted told her to sleep with her co-star William Baldwin while making the erotic thriller Sliver in order to improve their chemistry. She said that Evans told her: “I should sleep with Billy Baldwin, because if I slept with Billy Baldwin, Billy Baldwin’s performance would get better, and we needed Billy to get better in the movie because that was the problem.”

Stone, then at the peak of her commercial power because of the recent success of Basic Instinct, refused point-blank to entertain the idea, and later described Evans as “one of the most bizarre human beings I ever encountered in the film business, and one of the most inappropriate.”

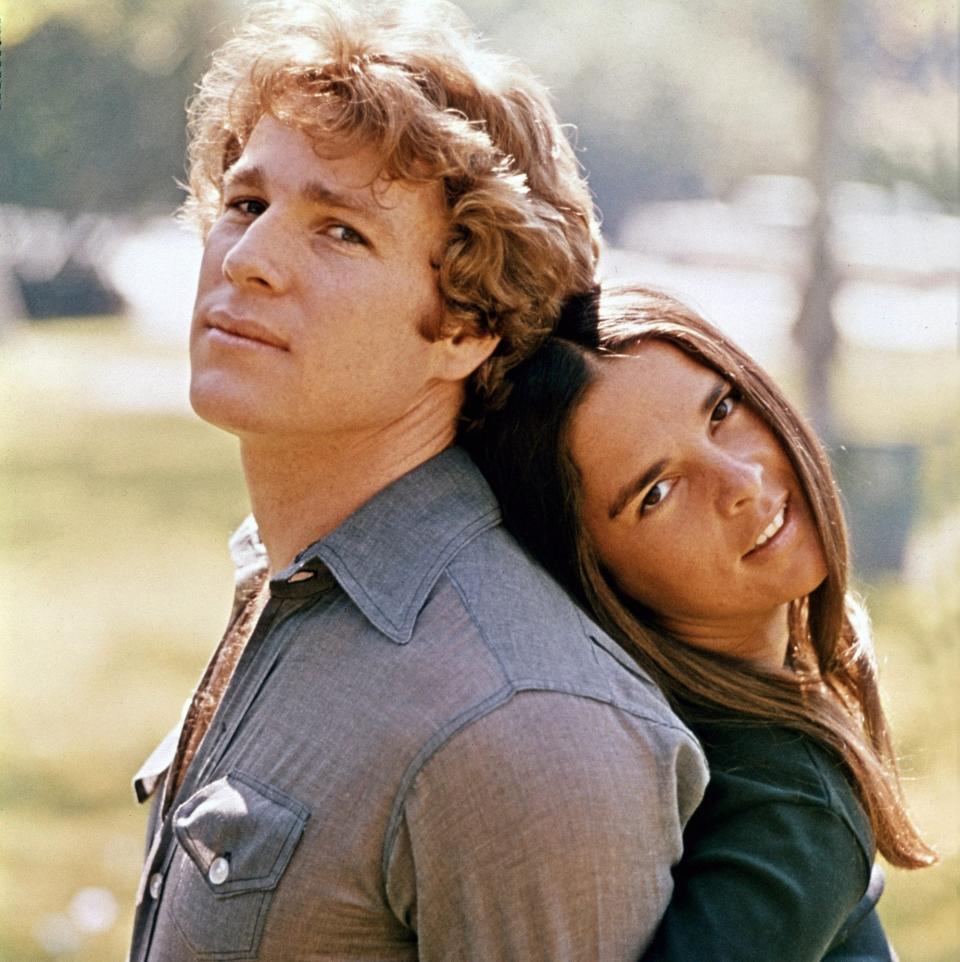

Evans himself boasted to Stone, while attempting to convince her to undertake this particular exercise in Method acting, that he had slept with Ava Gardner in order to elicit the right degree of performance while appearing opposite her in the 1957 Hemingway adaptation The Sun Also Rises. He was certainly a prolific husband, marrying seven times over the course of his life, and his most famous relationship was with the actress Ali MacGraw, who, in a supreme degree of confidence (or nepotism) he had cast in the film Love Story, which was produced by Paramount: the studio that he was running at the time. He was repaid by the film becoming a smash hit.

There was no off-screen romance between MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal, the film’s star, although she kissed him so hard at the screen test that O’Neal was sure both that he had the job, and wondered if there was something else between them, only to be disabused when a mutual friend informed him that MacGraw kissed everybody that hard.

A different kind of love, however, blossomed a couple of years later between she and Steve McQueen when they appeared in Walter Hill’s crime thriller The Getaway; ironically, she had not wanted to take the role, but Evans had pressured her into it, saying that it would be good for her career. He later regretted not listening to his wife. “Ali warned me, ‘I’m a hot lady. Never leave me for more than two weeks,’” he said. The marriage crumbled and she subsequently married her co-star instead, leading to lifelong regrets on Evans’s part.

But these encounters were all at least consensual, and Stone was able to refuse her producer’s blandishments. Before Evans had begun his career in earnest, however, the rigours of the casting couch in Hollywood meant that, rather than leading men and ladies being auditioned to see if they could fall in love with each other convincingly, the moguls simply took their favourite starlets and placed them under contract. They were then cast opposite whichever actor was similarly in favour with the studio.

This led to deeply grim behaviour that constituted, at the minimum, sexual abuse and exploitation – often much worse. The notorious Louis B. Mayer, co-founder of MGM Studios, wielded such power in Hollywood that he backed up his threats to ruin careers with action; when the actress Jean Howard, the target of his advances, not only refused them but married the agent Charles K. Feldman, Mayer saw to it not only that Feldman was banned from the MGM premises, but also that his clients were barred from appearing in his productions.

Yet this was a man who would hold meetings with a teenage Judy Garland sitting on his lap, almost absent-mindedly groping her as he pressed for some big-money deal or other. As the Hollywood historian and author Carl Beauchamp put it: “Mayer believed he’d built his studio brick by brick, it was his town, and he was king, so therefore he deserved all the perks of the kingdom.”

Many of the victims of this kind of abuse were scarred forever. Marilyn Monroe, a notable veteran of the casting couch, later wrote of the studio heads in her memoir My Story that “I met them all. Phoniness and failure were all over them. Some were vicious and crooked. But they were as near to the movies as you could get. So you sat with them, listening to their lies and schemes. And you saw Hollywood with their eyes — an overcrowded brothel, a merry-go-round with beds for horses.”

It may have been because of the legacy of this mistreatment that Monroe, for all her undoubted beauty and glamour, often had frosty relationships with her co-stars. The froideur that occurred between her and Laurence Olivier on the set of the film The Prince and the Showgirl later inspired the picture My Week with Marilyn, while her Some Like It Hot co-star Tony Curtis famously (and ungallantly) described love scenes with her as “like kissing Hitler”. He later also claimed to have had a romantic affair with her, which he described as “unforgettable”; with Monroe long since dead, there was no possibility of verifying or denying his claims, but the chemistry on-screen between the two actors remains one of the comic highpoints of cinema.

This is more than can be said for many other duos, where chemistry tests either had never taken place or had proved to be erroneous. Although Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie’s electrifying chemistry both on and off-screen while making Mr and Mrs Smith led to the Brangelina phenomenon, lightning failed to strike twice while Jolie was making the Johnny Depp comedy-thriller The Tourist. The resultant awkwardness between the two would destroy the film’s credibility.

Yet there have been even more dismal examples of mismatched couples, whether it’s Julia Roberts branding her co-star Nick Nolte in the forgotten romantic comedy I Love Trouble as “completely disgusting” (he responded that “[she’s] not a nice person, everyone knows that”) or Sophia Loren attacking Marlon Brando for groping her on the set of A Countess for Hong Kong, after which she said “He never did it again but it was very difficult working with him after that.”

Sometimes, of course, off-screen rows can lead to blistering on-screen relationships. Debra Winger and Richard Gere made a smouldering couple in the much-loved romantic drama An Officer and a Gentleman, but there was little affection when the cameras were turned off; Winger said that being with Gere was “like talking to a brick wall”, although she also allowed that “we had bad men running the show and so it kind of dirties the water.”

And even if Patrick Swayze’s romance with Jennifer Grey in Dirty Dancing made it one of the Eighties’ most popular films, Swayze found dealing with his co-star trying, writing of her in his memoir that “She’d slip into silly moods, forcing us to do scenes over and over. She seemed particularly emotional, sometimes bursting into tears if someone criticized her.”

Tension, if harnessed correctly by a skilled filmmaker, could even bring out the best, rather than worst, in a situation. Sean Young and Harrison Ford famously loathed one another on the set of Blade Runner, with their love scene being labelled a “hate scene” by those who worked on set, but Ridley Scott was able to turn this to the film’s advantage, creating a greater layer of ambiguity as to which of the characters was a supposedly emotionless replicant and which was a human being.

By the time that Young was digitally resurrected for her reappearance in the sequel, Blade Runner 2049, the look of intermingled surprise and horror that Ford’s character greeted her with on screen could either be put down to his skills as an actor, or reminiscence of what had happened between the two three and a half decades before.

Nor have more recent experiences between actors been pleasant ones. When Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson first auditioned for the Twilight saga, they met in the bedroom of the director Catherine Hardwicke’s house and were asked to attempt one of the script’s innumerable love scenes, to which Pattinson went full method. In Hardwicke’s recollection, “They did the kissing scene and he fell off and landed right there on this floor. Rob was so into it, he fell off the bed. I’m like, ‘Dude, calm down.’”

An additional problem was that, whatever the circumstances of their audition, Stewart was still a minor. As Hardwicke said, “I thought, ‘Oh my god, Kristen was 17, I don’t want to get in some illegal thing.’ So I remember I told Rob, ‘By the way, Kristen is 17. In our country, it’s illegal for them to have sexual relations.’ And he’s like, ‘Oh, OK, whatever.’” At the time, Pattinson was 21. During filming of the series, he and Stewart famously became a couple, before equally famously splitting after her affair with her Snow White and the Huntsman director Rupert Sanders.

Likewise, although the Fifty Shades of Grey series was widely criticised for the apparent absence of chemistry between its stars Jamie Dornan and Dakota Johnson, the meeting between the originally cast Charlie Hunnam and Johnson – masterminded by the original film’s director Sam Taylor-Johnson – sounds distinctly queasy. After the previous actresses who auditioned with Hunnam (and had to be “kissed and squeezed” by him) were judged to be too passive, a far more intimate audition was arranged at an LA hotel room, in which Taylor-Johnson was said to have pushed the pair to their limits “in every sense”.

Whatever happened in the hotel room, Johnson was successful in obtaining the part. Hunnam, however, subsequently dropped out, citing “something of a nervous breakdown”. It is not difficult to infer that something may have gone awry in this particular chemistry test.