'To Kill a Mockingbird' star Mary Badham reveals why Barack Obama reminded her of Gregory Peck

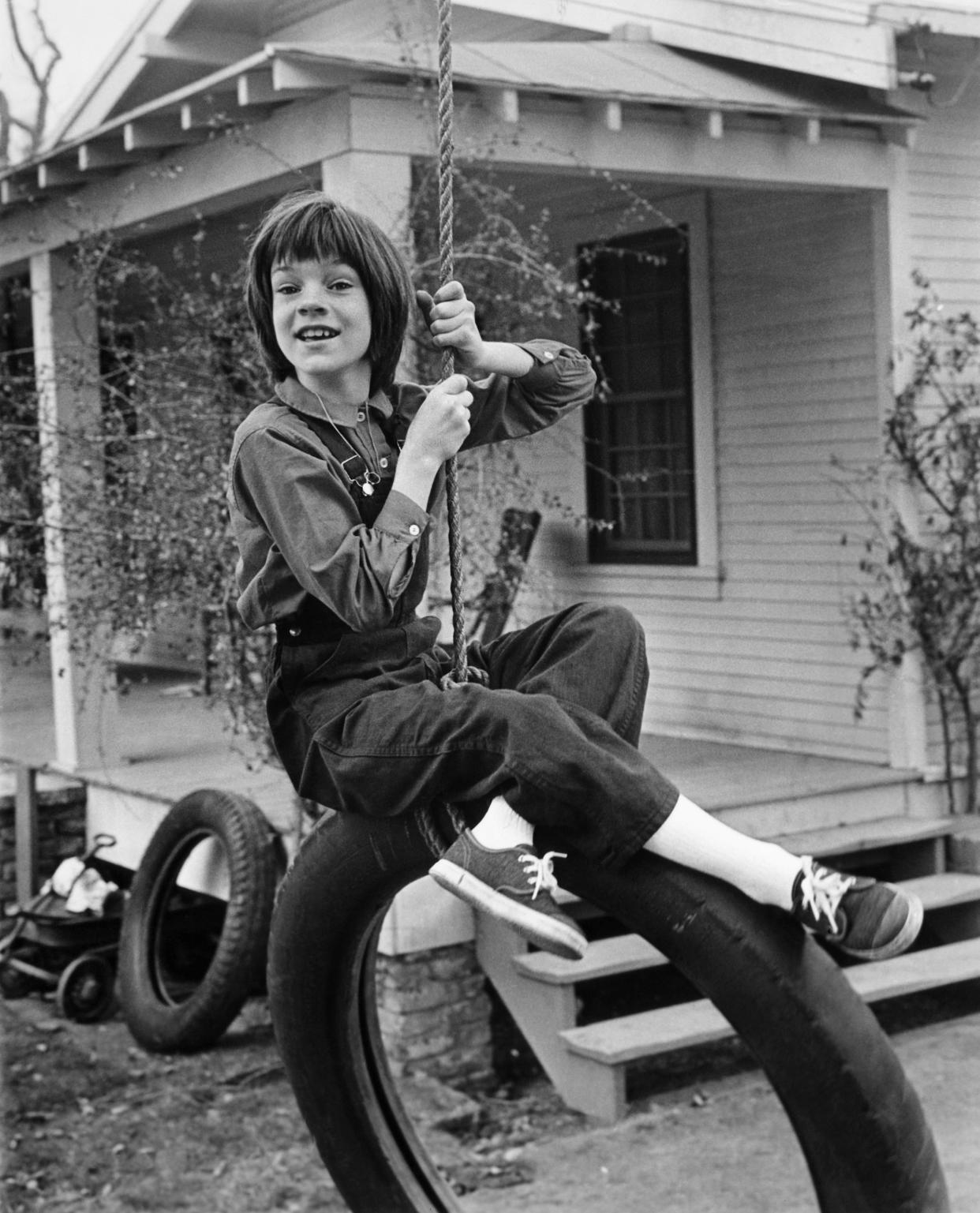

To Kill a Mockingbird’s status as a classic film is built on the riveting performances of Gregory Peck as lawyer Atticus Finch, and 9-year-old Mary Badham as his daughter, Scout. It has been said many times that Peck was the real Atticus, a charismatic family man who devoted much of his life to helping others. But as I watched the 1962 movie in anticipation of its return to theaters, Atticus’s calm demeanor and unpretentious eloquence reminded me of someone else: former President Barack Obama. When I brought up the comparison with Badham, who met Obama at a 2012 White House screening of To Kill a Mockingbird, she burst out laughing.

“That’s right! Absolutely,” Badham, 66, told Yahoo Entertainment. “And it’s funny because having been with the president, I had the same thought when we were together. He’s got that sense of humor. He puts people at ease as soon as he walks in the door.”

If anyone can speak to Gregory Peck’s character, it’s Badham. During filming, both Peck and Brock Peters (who played the falsely accused Tom Robinson) became father figures to Badham, helping her to feel at home as the lone girl on her first film set. And as she grew to be an adult, the two actors inspired her to keep spreading the film’s message of tolerance.

That message still holds power for audiences. To Kill a Mockingbird, released on the heels of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel, follows events in the life of 6-year-old Jean Louise “Scout” Finch (Badham) over several months in Depression-era rural Alabama. The story is told from her perspective, as the scrappy, thoughtful girl begins to wake up to the violence and bigotry of the world around her. The film’s main event is a trial, during which attorney Atticus passionately defends an African-American man (Peters) who has been accused of rape, despite blowback from his own white community. Though Tom Robinson is clearly innocent, the white jury finds him guilty and his character meets a tragic end. Nevertheless, Atticus continues to uphold the values he teaches his children: fighting discrimination whenever possible, challenging assumptions about race and class, and upholding nonviolence.

Of course, much of this went over Badham’s head when she was making the movie. She remembers those five months as “play time.” But when she saw the completed film, the actress connected its depiction of racism in the 1930s to something she’d witnessed in her own Alabama hometown in the 1960s. The story involved a woman named Beddie Harris, whom Badham described as “my Calpurnia” (referring to the African-American housekeeper who looks after Atticus’s children in To Kill a Mockingbird, played in the film by Estelle Evans).

“Beddie and I had to ride on the back of the bus. You know, she would take me around,” Badham said. “And I remember one Easter, we’d gone down to get the clothes and the shoes and the hat and gloves, and all the nine yards that you had to have back then, and we got on the bus. It was packed like sardines in the back. There were plenty of open seats in the white section, but we couldn’t sit there. So we sat in the first seat beyond that.

“And this big white bus driver — when he looked in the mirror, he slams on the brakes and he comes back there and gets real ugly with Beddie. I never, ever had heard anything like that in my life. It scared me to death. And poor Beddie was just totally mortified and she had to sit back in the back, partially on the laps of two black gentleman in the back. It was just horrible.”

Working on To Kill a Mockingbird had opened Badham’s eyes to discrimination in the Deep South. When she returned home from shooting on the Universal Studios backlot (where the Boo Radley house still stands), she couldn’t close them again.

“When I went to California, I had friends of all races colors and creeds and it was wonderful,” the Birmingham native said. “And then having to go back to Alabama and dealing with being put back in a box and not being able to speak unless spoken to, and if a black man so much as looked me in the face he could be killed, literally … When I was 14, 15 years old, I was like, I’m out of here. I can’t do this anymore. And I left.”

Despite being Oscar-nominated for her role as Scout (the youngest-ever Best Supporting Actress nominee at the time), Badham took just four more acting jobs, including a Twilight Zone episode, before retiring from show business. (Her half-brother John Badham, a film student at Yale when Mary was cast in Mockingbird, carried on the family’s Hollywood legacy, directing films like Saturday Night Fever and WarGames.) Mary completed her education, relocated to Arizona (she now lives in Florida), and moved on to other endeavors, including art restoration and raising a family.

But her Mockingbird co-stars Peck and Peters were still a part of her life. She remained close with both actors until their deaths in the early ’00s, occasionally spending weekends with the Peck family or listening to jazz musicians jam at Brock and Didi Peters’ house. The two actors, both activists who fought racism and anti-Semitism throughout their lives, instilled in Badham the idea “that the work we did had to mean something.”

In other words: To Kill a Mockingbird was not just an acting job; it was a lifelong responsibility. Badham realized what this meant for her when, as a young mother, she received a call from a college professor, asking her to speak to his class about the film. Since then, she has spent decades traveling around the country, talking to young people about tolerance and the harsh realities of the Jim Crow South.

Watching the film nearly 60 years after it premiered, I found To Kill a Mockingbird to be a very good film, but not a progressive one. It has clear elements of the “white savior narrative,” in which a white character experiences personal growth by helping black characters fight racism, while the black characters’ perspectives are downplayed or disregarded. As Roger Ebert pointed out in a 2001 essay on To Kill a Mockingbird: when the “guilty” verdict is read, the camera shows Atticus’s reaction, not Tom’s; when Atticus goes to a black neighborhood to report Tom’s death, the black characters are given neither lines nor closeups; and the scene in which Scout single-handedly stops a lynch mob is extreme wishful thinking, since racially motivated lynchings were shockingly common in Southern states prior to 1950.

Some of these elements were addressed by writer Aaron Sorkin in his new Broadway production of To Kill a Mockingbird, which gives larger roles to the characters of Calpurnia and Tom, and shows that Atticus has his own biases to overcome. While purists may have balked at the idea of tweaking Harper Lee’s story, Badham loved Sorkin’s version — and believes that To Kill a Mockingbird’s message is too important to keep preserved in amber.

“When you take a subject matter as serious as the subject matter that we’re dealing with, it is it is art to be able to look at it from different directions, different viewpoints, or to give it more robustness maybe then it had before,” she said. “That’s what art is all about.”

To Kill a Mockingbird, part of the TCM Big Screen Classic Series from Fathom Events, will play in theaters for four showtimes only on March 24 and 27. For tickets, visit FathomEvents.com.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Want daily pop culture news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Entertainment & Lifestyle’s newsletter.