Jimmy Page Is Still Practicing

“I don’t do face calls and all of that,” says Jimmy Page. “Because I’m a creature of habit, I usually end up holding the phone to my ear as opposed to looking at the image.”

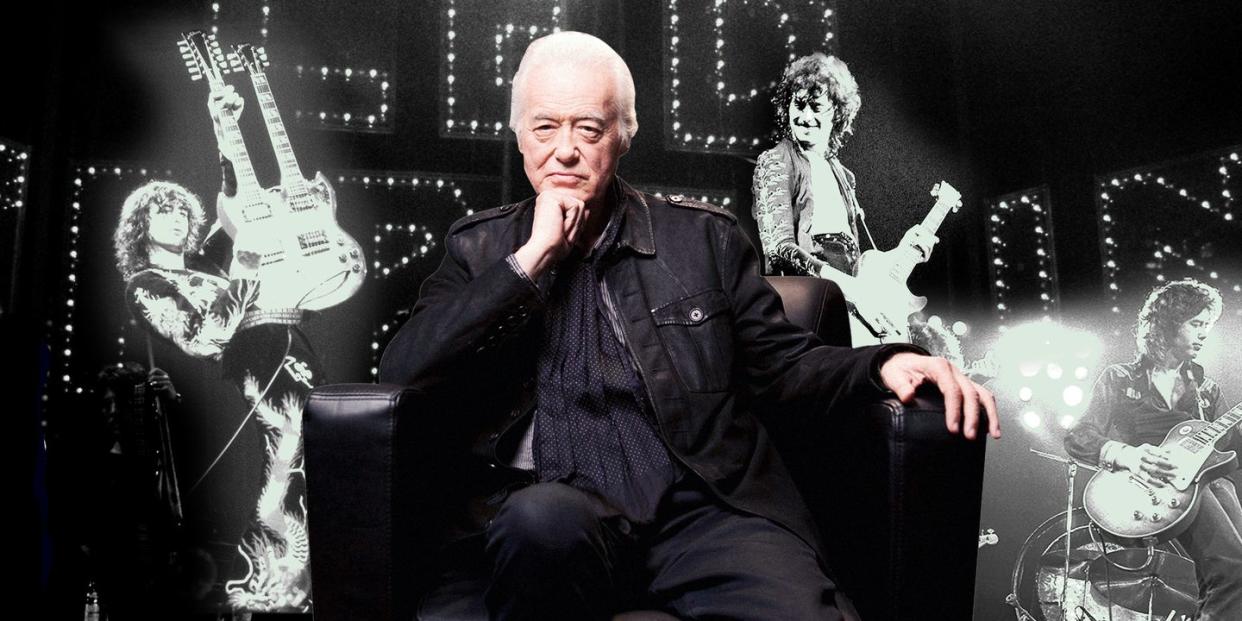

Fair enough. So a regular call it is from a chatty and affable Page, 76, who is currently riding out the pandemic at his home in Southeast England. The occasion is the release of the new photo collection Jimmy Page: The Anthology, which gathers hundreds of images spanning the career of this guitar colossus, from his days as an in-demand session musician up to his recent oversight of reissues of the Led Zeppelin catalogue and his participation in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Play it Loud” instrument exhibit. The twist is that the book (which was first published earlier this year as a very pricey signed limited edition) focuses on items from his personal archive—studio notes, stage costumes and, of course, gaggles of guitars and piles of musical gear.

The Anthology is something of a companion to his 2014 book Jimmy Page by Jimmy Page. “The first book was the autobiography in photographs,” he says. “That’s something I always wanted to do, because I don’t know anyone else who has done something like that. But this one is the detail behind the detail, so you get close up and personal with things, even quite invasive with the guitars—if they’d seen a photograph of the dragon suit, now they’re going to be able to see it in really close detail.”

Mostly, The Anthology illustrates the tale of a boy whose family moved into a house where the previous owners had left a guitar, an accident that set him on a lifelong quest. “The guitar made an intervention into my life, that’s the way I see it,” he says. “And then I became totally obsessed—the guitar just became another limb, like it was grafted on.”

Along the way, Page’s text covers moments like acquiring a sitar in 1962, years before George Harrison discovered Indian music, or playing sessions with Nico and checking out the Velvet Underground in a New York nightclub (“They were incredible,” he says, “I could never work out why people weren’t going to see them”).

Other parts of the story, like the vision for and recording of Led Zeppelin’s earth-shaking first album, are broken down step by step. “It was all moving so fast,” he says of that record’s creation. “You wouldn’t be able to catch your breath at the pace this stuff was being done at. It wasn’t being done in a hurry, it was just on a mission.”

It’s been years since we got new music from Page; most of his efforts in the 21st Century have focused on maintaining and burnishing Led Zeppelin’s legacy. But when you’ve seen and done the things he has, you have to wonder what there is left to prove.

“When I look back on it,” says Jimmy Page, “it feels something like a charmed life.”

Esquire: How are you holding up through quarantine? What’s a typical day for Jimmy Page?

Jimmy Page: I locked down in February. It was rumored that the over-70s were going to be locked down, so I was being pretty cautious anyway and really keeping my distance. I’m very fortunate that I have a place in the country as opposed to my main place, which is in London, so I went out there and basically been locked down ever since.

Initially, it gave the opportunity to deal with the things that you were always complaining about because you didn’t have enough time! It was good to be able to sort out my books in the library and actually do some reading—I’m pretty bad about getting books and then not reading them. So it was a good opportunity to catch up with that, and to properly visit my record collection and get that into order.

My routine was, after I had breakfast, I started playing the guitar, because I had so much administrative work to do that I wasn’t playing as much as I wanted to. Then more recently, the emails started flying around again and you get back into the admin stuff, but I haven’t stopped playing the guitar.

Are you playing towards any particular end?

Basically, if I play the guitar, I usually come up with new stuff anyway. I’ve always done that, going back to being a session musician. Playing around on some theme, or something from the past, I’ll come up with something that I didn’t have before. It’s not “Oh, my God, stop the world,” but it means that flair for spontaneity hasn’t left me—and I’m touching wood, because it would be a sad day if it ever does.

So I was doing things like checking out exactly how I played certain things on the records, because over the years, they would mutate a bit, so I thought, let’s see exactly what it was. But one thing I didn’t ever do was to play scales. When I did guitar magazine interviews, they always looked at me in amazement because I didn’t practice scales. I guess I had so much other stuff that I actually wanted to play and practice. This comes with being an unschooled musician; I’ve got my own ways of doing things.

Why did you start keeping all of this ephemera, especially from the early years, that we see in the book? Did you have a sense that this stuff could turn out to be important?

It’s interesting, isn’t it? Somebody asked, are you a hoarder? No, but the point is that I knew at the time that what I was involved in was really a phenomenon—since hitting in the ‘50s, when rock and roll kicked off—and I gave my life to that, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I didn’t think I was going to be successful at it, I’ve got to say, but I just knew that’s what I wanted to be part of.

So all of these things happened, like being a studio musician and having these diaries where you would you log in the sessions that you had coming up. Bit by bit, I collected those sort of things. When I moved houses, I had two suitcases full and I didn’t want this stuff to be mislaid, so I left it with my parents. But I did carry on collecting things, in an archive sort of way—being the producer of Led Zeppelin, I had all the acetates and test pressings, some of the clothes that I wore as a studio musician, or even a drawing that I did on the back of a music book.

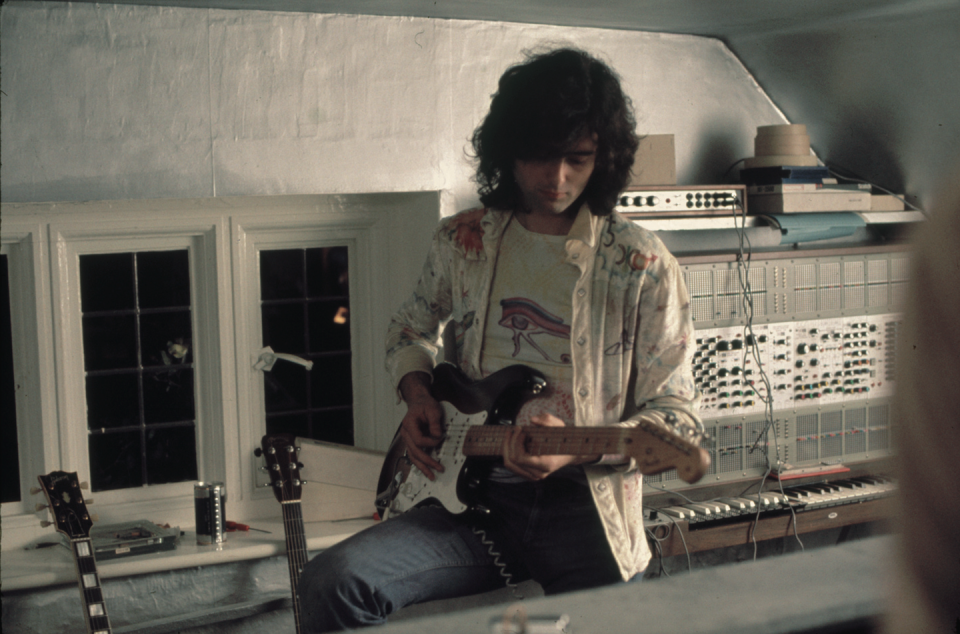

When you think back on sessions, do you think of them in terms of the gear and the set-up? Is that what defines, say, recording “Stairway to Heaven” for you?

I thought for the book, it would be interesting to pick one or two songs from each album and show the equipment that was used as best I could. So the classic one is that you’ve got the Harmony guitar—the first four albums were all written on that guitar, and “Stairway” was played on that guitar. Then the first overdubs were on electric 12-strings, one a Vox and one a Fender. So the set-up for the photograph is the guitar it was written on, and on each side is the 12-string that make up all the texture. But then the big thing about it was, how am I going to do this live? And that’s when I came across the idea of doing it on the double neck because I could pull off the 6-string work and the 12-string work on one guitar.

So what the photograph portrays is that these are the instruments that were literally used on “Stairway,” and then this was the guitar that needed to be acquired in order to play the song live. It gives people an inside view, where they maybe read about this stuff in the past, I wanted to be really authoritative with what I was doing.

Last month was the fortieth anniversary of John Bonham’s passing. What thoughts did that bring up?

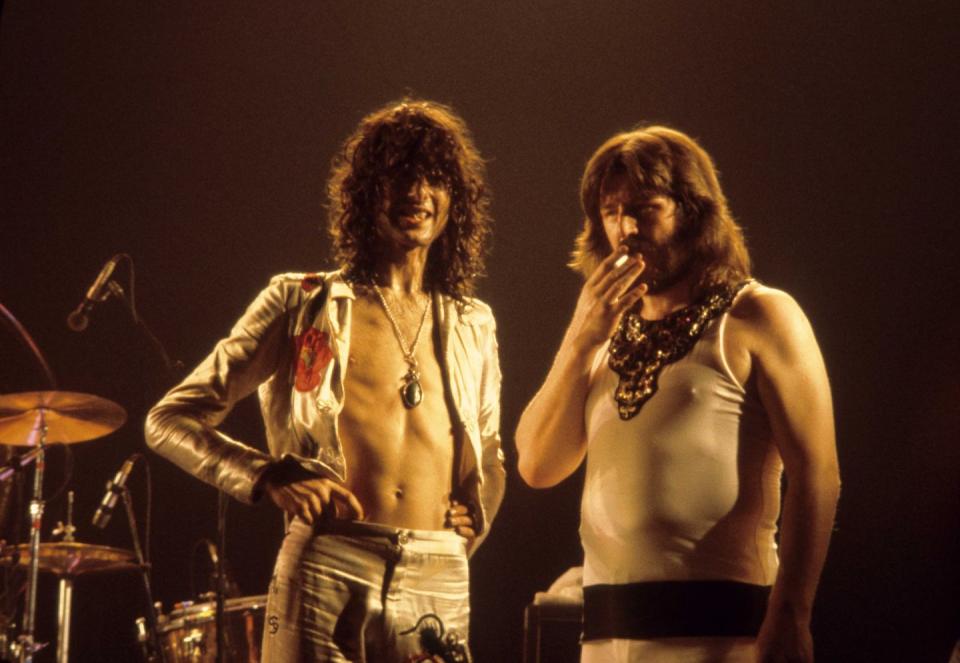

I could go on for hours and hours talking about John Bonham. But on that first album, the very first track is “Good Times Bad Times.” And I think I can safely say that the drum pattern on that song changed drumming overnight. He brought an attitude to the drums that hadn’t existed before, and he developed so many techniques along the way that nobody had even thought of.

It was just wonderful working with him. I just loved it. You’d have these long improvisations like on “Dazed and Confused”—the thing started getting longer and longer, it got like a classical piece, in movements—and it was all guitar-led, but we were so in sync with each other that you could try all this stuff. I’d give him the nod and he would know something was coming and it was almost like ESP—not only with him, all the band, but that was the key character I was working with.

It’s such a tragic loss, just for the music he would have been making all those years. Who knows what he would have done? I hope I would have done it with him along the way.

The last Zeppelin project that was announced was a documentary for the band’s fiftieth anniversary. What’s going on with that?

Well, I did all my parts for it. I can’t give you any of the secrets away. I’m not sure but I think that it’s got slowed up relative to the Covid virus. So I can’t give you the exact date, but I’m sure it will get finished.

But it does hit, the way the virus has changed everything. On the previous book, there were all these marvelous things I was able to do. I did a Q&A at the Ace Hotel in LA with Chris Cornell, all these interesting events, different ways to do book signings. I always like to think of things that are different to what others are doing.

Well, we all need to think about doing things differently now.

Yes, we have, haven’t we? I better keep practicing the guitar. Maybe I might even be able to play it live outside.

Have you thought about doing any kind of virtual performances or events?

Well, one of the reasons why I enjoyed being in groups when I was young was the camaraderie, the ambience of the concert and the audience—though I must admit that in the early days, there wasn’t that many that came along. But it was that whole thing of playing with other musicians and having that musical conversation. I’m not the sort of person where, “We’re doing this record out in LA, let’s send the file to Jimmy Page and he’ll put his guitar on there.” I don’t do that. So I couldn’t really see me doing something on the screen, on Zoom or one of those. But it’s hard to say, because in another six months I might be craving doing it on Zoom.

Does it make you think that when things come back, you’d be more eager to play?

I’m not thinking about going back out there. I’m working on quite a lot of stuff at the moment. I’m always working on projects, and more often than not, on projects that have multiple installments, like my website or the Led Zeppelin re-releases. So that’s the sort of level that I go into things, it’s not just some sort of yes, no, sign off without really knowing what it is. I get right in there—and that’s a good way to summarize the book, I get right in there with every sort of detail. So who knows what the next thing will be, but I can guarantee I’ll have put a lot of work into it.

You Might Also Like