How Iron Maiden grew up - the story of Powerslave

In January 1984, when Iron Maiden arrived at Le Chalet Hotel in Jersey, in the Channel Islands to begin writing material for their next album, they were five men on a mission. The previous 12 months had seen them accomplish a successful career transition from standard bearers for the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal into internationally recognised rock stars with their first headline tour of America, including prestige shows at New York’s Madison Square Garden and Los Angeles’s Long Beach Arena – and their first US Top 20 album with Piece Of Mind. Now it was time to bring the hammer down.

“For me, Piece Of Mind was the best album we’d done up to that point,” Maiden bassist and founder Steve Harris told me. “People still talked about [previous Maiden album] The Number Of The Beast, because of the title track and Run To The Hills, which were both big hits, and because it was Bruce’s [Dickinson, singer] first album [with Maiden]. But Piece Of Mind was the one for me.”

The first Maiden album to feature the classic line-up of Harris, Dickinson, guitarists Dave Murray and Adrian Smith and drummer Nicko McBrain, Piece Of Mind was also the first record to fully integrate Dickinson as a songwriter. He had written Run To The Hills, Maiden’s first Top 10 single, but it was on Piece Of Mind that he began the songwriting partnership with Smith that would flourish more fully over the coming years, not least on the bugling, Dio-esque Flight Of Icarus, one of the album’s two chart singles.

However, it was the other song Dickinson co-wrote with Smith that really demonstrated what they would bring to Maiden: Sunlight And Steel, which introduced an extra-large dose of rock groove to Maiden’s trademark galloping metal.

“I never saw myself as a heavy-metal speed merchant,” Smith told me. “Definitely not a shredder! I grew up listening to Eric Clapton and the sort of blues rock that bands like Zeppelin and Purple were doing. I loved rock guitar, but it had to have melody.”

“We both grew up loving Machine Head by Deep Purple,” Dickinson recalled. “It was definitely part of the appeal that Ian Gillan was such a great singer and Ritchie Blackmore was such an awe-inspiring guitarist, but it was the songs that mattered to us most – all the ones that got you first time, like Smoke On The Water and Highway Star. So when Adrian and I first started writing together it was natural we would gravitate more to that kind of thing. “

Steve Harris, of course, had his own mathematical notions of groove. Groove was good. Melody was welcomed, but unless it was sewn into the fabric of something more complex and high-wire, it simply didn’t resonate for him. Harris had never really been into singles. He was into prog.

The evidence had been there from the band’s debut album, in 1980, on the seven-minute-plus Phantom Of The Opera. It was there in excelsis on Hallowed Be Thy Name from Number Of The Beast, and as the epic grand finale to Piece Of Mind, in To Tame A Land. All epics written solely by Harris.

As founder, leader, chief songwriter and ultimate decision maker, ’Arry, as everyone except Bruce called him, ensured that Maiden’s chief focus, musically, would always remain on the pure, unsullied force of the hardest, fastest, most technically acrobatic and undeniably heavy fucking metal you ever heard.

Frequent line-up changes – replacing a key guitarist, their drummer, even their singer – that would have killed the career of lesser titans seemed only to drive Maiden on. Harris was right: Piece Of Mind was their best album to date. All they had to do now was follow it up with something at least as good, hopefully even better. No small task. Harris, though, refused to acknowledge that he and the band were under pressure.

“People kept talking about pressure, and looking back I can obviously see why. But the truth is I didn’t really feel any at the time,” he shrugged. “It wasn’t arrogance. I just never worried about what we had done before or what other people – management, record companies, tour promoters, the music press – expected of us. Not when it came to writing new material.

“My priorities were simple. Number one, I have to like it. If I think something we’ve done is really good, then it doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks. Number two, the fans have to like it. If I like it and the fans like it, that’s all that ever matters to me. The critics can say what they like after that, it won’t matter to me.”

Dickinson also felt blissfully unconstrained by the weight of expectation that now sat on Maiden’s shoulders. Still only 25, as he later told me: “My main memory of writing songs in Jersey is of excitement. We’d just come off a really successful world tour, and as a band we were still at peak velocity, as it were. Meanwhile, we were stuck in this out-of-season hotel. It was too bloody cold to go out, and there was nowhere to go anyway.”

Plus, as Harris pointed out, “the hotel bar was open round the clock and it was free, so we probably spent the first week or so getting pissed!”

Another factor adding to their collective oomph was that Maiden’s fifth album would be their first with the same line-up as its predecessor. Harris always dictated that ahead of any new album, they commit to a designated writing period, which in in this case was six weeks.

“I don’t write on the road,” he explained. “I prefer to be with the band in the studio.” However, Dickinson had already come up with the song that was to give the album its title and conceptual theme: Powerslave. According to Smith: “He’d done the Piece Of Mind tour with this horrible little four-track machine full of ideas, riffs, arrangements and whatever, and the Egyptian thing was on there. Everyone he spoke to about it was really taken by the theme, so that’s where we went.”

Dickinson had written the song Powerslave alone. But it was the rock monster he and Smith came up with one night in Jersey that broke new ground for Iron Maiden.

The guitarist had been working on the riff in his hotel room when Dickinson knocked on his door. “I played him the music. He started singing, and we had 2 Minutes To Midnight. We wrote it in about twenty minutes.

“I could knock out stuff like that all day. But it didn’t always fit into the kind of fantasy-horror thing that Maiden had going for them. In the early days I needed Bruce to help me make things more how Maiden would want them. 2 Minutes To Midnight is a perfect example of that. I had the right riff and Bruce had the right words.”

With a flashing switchblade riff that could have come from the first Montrose album, and a chorus from Deep Purple’s Burn, 2 Minutes To Midnight was joyous, almost gleeful. Yet the nuclear-doomsday lyrics were almost comically bleak: lots of killing ‘the unborn in the womb’, and warnings of ‘demon’s seed’ and ‘children torn in two’. In 1984 this was heavy metal at its zenith.

“2 Minutes To Midnight deals with a very gory subject,” Dickinson agreed, “and some of the lyrics are distinctly unpleasant. But that’s just as it should be, because [nuclear war] is a very unpleasant subject.”

2 Minutes To Midnight was the obvious choice as the first single from the album, and, sure enough, it became a sizeable UK hit, fizzing to No.12. It was Harris who came up with what became the second single, a red-hot slab of peak Maiden titled Aces High, a soulful call-to-arms in the tradition of Where Eagles Dare from Piece…, only punchier, angrier.

Aces High was heavy artillery bass and whizbang, Spitfire guitars, machine-gun drums and air-raid-siren vocals. Sure enough, that single also roared into the UK Top 20.

The most important new number begun in Jersey, however, was Harris’s monumental musical retelling of the 18th-century Samuel Taylor Coleridge gothic poem The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner. Coleridge was a notorious dope fiend, and The Rime is full of richly evocative verbiage about ‘the wrath of spirits… from the land of mist and snow’. As a poem worth reading now, I wouldn’t urge any hurry. Far too much about an albatross. Musically, however, in the hands of a dedicated metal music maestro like Harris, at 27 working at his absolute peak, Coleridge’s trippy peregrinations took on a whole new dimension of gothic splendour – and horror.

The band sketched out another handful of songs in Jersey, but it wasn’t until they arrived at Compass Points Studios in Nassau, in the Bahamas, with producer Martin Birch (or ‘Pool Bully’, as he would be credited) that things really began to cook. It was clear from the start that the album’s strength would centre on 2 Minutes To Midnight, Aces High, Powerslave and Rime Of The Ancient Mainer.

Of the other four tracks, only Harris’s suitably swashbuckling The Duellists, inspired by the 1977 Ridley Scott film of the same name, really cut muster, such was the elevated standard the band had now set themselves. Bill Hobbs, who had choreographed the film’s fight scenes, coincidentally founded the fencing club of which Dickinson – an Olympic-level fencer – was a member. Dickinson’s own Flash Of The Blade just about qualified, too, but surely one song about sword fighting per album was enough?

No Maiden fan’s life was going to be any the poorer, either, for having skipped Dickinson and Smith’s blustering Back In The Village – revisiting the theme of The Prisoner from the Number Of The Beast album, only far less interestingly. Dickinson finished the lyrics for 2 Minutes To Midnight only once they had begun recording in earnest in the studio. Everyone could hear straight away that this was another Maiden classic in the mould of early riff monsters like Sanctuary and Wrathchild.

Dickinson’s personal best, however, was to be found in the mesmerising seven-minute title track, on which his use of Middle Eastern melodies, albeit rendered on a screaming electric guitar, and Egyptian mythology – both Horus, the falcon god, and his father Osiris, ruler of the underworld, are name-checked in the very first verse – created a brilliantly apt metaphor for the occult power of the rock gods, themselves ‘slaves to the power of death’.

As Dickinson later explained: “Powerslave is more than just about the ancient Egyptians. It was also about us, the band, and what was happening to us. I’d been on a non-stop rollercoaster since joining the band two years before. The tours were getting longer and crazier, and the expectations around us were astronomical by the time we came to Powerslave. We were slaves to the power, whether musically or in terms of just chasing success. In fact, we were both.

“There was an ironic message, too, in the lyrics. When you had amplifiers powering a big PA system, you had ones just generating power and nothing else, and they were called slave amplifiers, because they were just slaves to the big amplifier. They were, literally, power slaves.”

The track also included an unexpectedly moving guitar interlude where Dave Murray and Adrian Smith entwine their solos, going from silk desert evening breezes at the start, to full-thrust adventures among the pharaohs and pyramids as the guitars lead the band into pure metal mayhem. It sounds like both guitarists have complete mastery of the moment.

In fact, Smith told me he was so horribly hungover when he recorded his part, “it nearly killed me”. He recalled how the night before, he and the band “were having a bit of a late night in the studio”. “We were partying and doing guitar overdubs at the same time. Which turned more into just partying, to be honest. I went to bed fairly drunk at about three a.m., not expecting to work the next morning.”

Producer Martin Birch usually never called anyone into the studio before noon. This time he phoned the still delirious Smith at 10am. “He said come down and do some more work. My head was pounding, but I went down to the studio. It turned out the reason Martin was ready to go was because he hadn’t been to bed at all yet.”

Birch had stayed up the rest of the night with singer Robert Palmer, who was about to make his fourth album at Compass Point. At the time, Palmer virtually lived on the island. No slouch himself when it came to “the playboy lifestyle”, as Birch laughingly recalled, when Palmer heard his mate Martin was back in the studio with Maiden he’d come to say hi to some fellow Brits.

Smith: “So the two of them are sat behind the desk as I walk in. They said: ‘Come on, then, what do you want to do?’ And I said Powerslave.”

A great singer, Palmer was also a formidable producer in his own right.

“Seeing him sitting there with Martin, waiting for me to play, I was pretty nervous, I have to admit. But I just went for the solo. It came off alright, and Robert Palmer really liked it too.”

The twice-as-nice paradise they found themselves in in Nassau certainly lent itself to all sorts of shenanigans during the band’s almost four-month stay.

Nicko McBrain told me that when he’d joined the band the year before, “everybody with the exception of Steve and Bruce was just fucking nuts! We were just going absolutely fucking crazy on everything we could possibly get our hands on! Nine times out of ten it was in the booze department, but, you know, we’d have a bit of ‘taboo’ and a bit of ‘yahoo’ and a little bit of livening up here and there.”

Not Steve Harris, though. Not in 1984 and not since. The ultra-highs he sought lay within the very fabric of Maiden’s music. His music. Something he took very seriously, no fucking around. Which is how he was able to turn his cathedral-like version of Coleridge’s Rime Of The Ancient Mariner into such a monumental musical achievement.

Even Smith, who admitted he was somewhat out of his comfort zone as a musician with such a demanding piece of work, recalled: “When Steve put Mariner forward I just knew we had to do it, because I’d never heard anyone do anything like it before. I remember how when we recorded it in the Bahamas, Steve had to hang the lyrics from the top of the wall all the way to the floor, there were so many for Bruce to learn. Steve was so fired up about it he convinced everyone else. It’s so dramatic, how can you not like it?”

For generations of Iron Maiden fans, Rime Of The Ancient Mariner remains the most fully realised of all Harris’s cinematically epic rock masterpieces. There would be others – the eight-minute-plus Alexander The Great on their next album, Somewhere In Time, the almost 10-minute-long title track to their 1988 album Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son; and there had been others before, such as Phantom Of The Opera, To Tame A Land – but none that captured so eerily or so definitively the strange, other-worldly place Harris summoned forth in his version of Rime Of The Ancient Mariner. A

masterful evocation of a complicated mood-piece that would become the dramatic cornerstone of the Maiden live spectacle for many years to come, it was also prophetic in terms of Maiden’s musical evolution, and that of heavy metal itself, with the coming wave of thrash- and speed-metal bands (led by Metallica, led by Lars Ulrich, who confessed in his youth to being “the biggest Maiden fan on the planet”) all drawing inspiration from its outlandish disregard for musical norms.

Indeed, Rime was so layered, so multi-sectioned and almost scientifically constructed, it became the blueprint for what just a few years later became known as progressive metal. Dream Theater, arch proponents of prog-metal, once described their early musical explorations as a fusion of Powerslave and Rush’s Hemispheres.

“It’s great that people love the more straightforward rock stuff, cos so do I,” said Harris. “But I know a lot of our fans checked out Coleridge just on the strength of our version of Rime. For me, knowing lots of kids in their teens discovered Coleridge’s work through our music is amazing. It was the same with To Tame A Land on Piece… So many people told me that after hearing it they went and read Dune by Frank Herbert, which inspired it.”

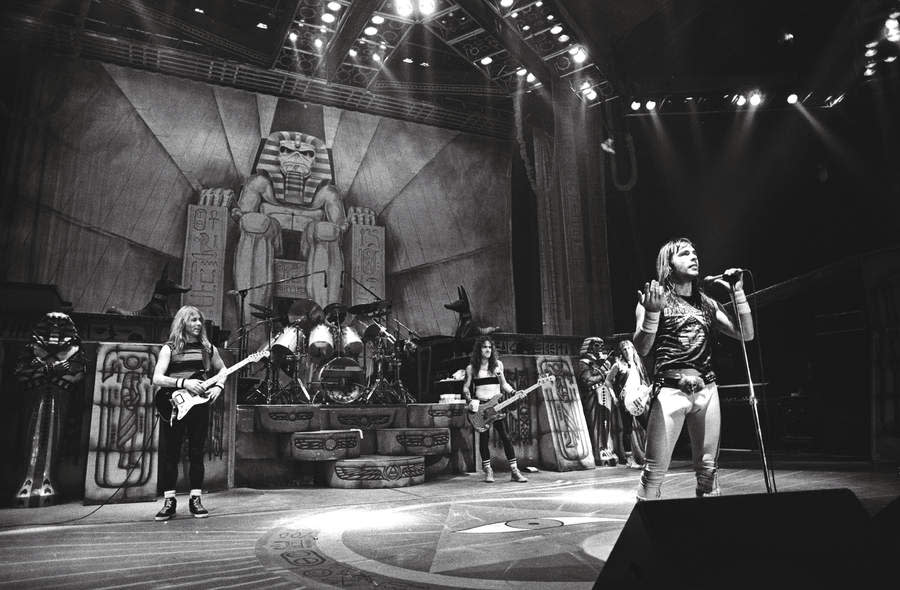

Equally impressive was the ancient Egyptian motif that the album sleeve and stage show would be based on. Dickinson’s title song of power-lust among the pyramids had inspired Maiden’s long-time sleeve designer Derek Riggs to create his most sophisticated artwork yet: Eddie’s ghastly immortal visage replacing that of the ancient pharaohs, as he sits, Sphinx-like, on his enormous desert throne, a monument to megalomania, as self-absorbed as the Sun.

On stage it was simply a question of bringing the album sleeve into three-dimensional life, topped off with a 30-foot mummified Eddie, eyes shooting fire. “Cos you think of Egypt and the pyramids, and really, how do you portray that without looking like Hawkwind?” said Harris. “But it was probably the best stage show we ever did.”

Dave Murray later told me that he remembered the Powerslave album as “the moment when we first realised we’d have to start taking things a bit more seriously”. “That was that start,” he said, “of us being aware we weren’t just young tearaways any more.”

In 1984, with Powerslave, the band had begun their metamorphosis into seasoned pros. In this respect also, Maiden’s fifth album would be a watershed in their career; the moment when, ready or not, the boys in the band were forced to step up and become men.

“It felt sort of like we had got to the top of the mountain with that one,” said Harris. “We had never really felt that way before. Everything up to then had been about climbing the mountain. With Powerslave it felt like we were looking out over the rest of the world.”

Released in September 1984, Powerslave was Iron Maiden’s second British No.1 album, and their second million-selling album in the US, where it reached No.12. It also heralded the start of World Slavery, the biggest, most successful tour they would ever undertake.

“It was the best tour we ever did and it was the worst,” said Dickinson. “And it nearly finished us off for good.”

Ultimately, Powerslave was a gloriously packaged, if somewhat patchy, collection of material: four absolute epics; four average joes.

“I think this album is superior to the previous one,” Dickinson told me. “We took what was best in Piece Of Mind, while stressing the aggressive style of Number Of The Beast.”

Harris felt the opposite. Looking back, he told me: “I still think of Powerslave as a really, really strong album. I think there are four standout tracks on there, all of which we did live, and that’s Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, 2 Minutes To Midnight, Powerslave itself and Aces High.

"Of the other tracks… there is some good ones. There’s The Duellists, which I still think is good, you know, its musically interesting. But if you put The Duellists against Rime Of The Ancient Mariner and 2 Minutes To Midnight… I mean, it’s just no way. But they weren’t filler songs or anything like that, I just think those four particular songs were really strong.”

Piece Of Mind would remain Harris’s favourite Iron Maiden album for some years, until they made Seventh Son Of A Seven Son in 1988.

Years later, Dickinson said: “Powerslave felt like the sort of natural rounding off of Piece Of Mind and Number Of The Beast, that whole sort of era. I remember listening back to it and I thought: ‘Um … this is great, but I don’t know how much more we can do of records that sound in this kind of vein.’”

Um… Time would tell…