Inside the Game-Changing Trial of 'Lady Chatterley's Lover'

In October 1960, Esquire dispatched writer Sybille Bedford to London’s criminal court, where she spent days reporting each and every beat of a star-studded trial. But the perp on the stand at the Old Bailey wasn’t a murderer, a cheat, or a thief—instead, it was a dirty novel.

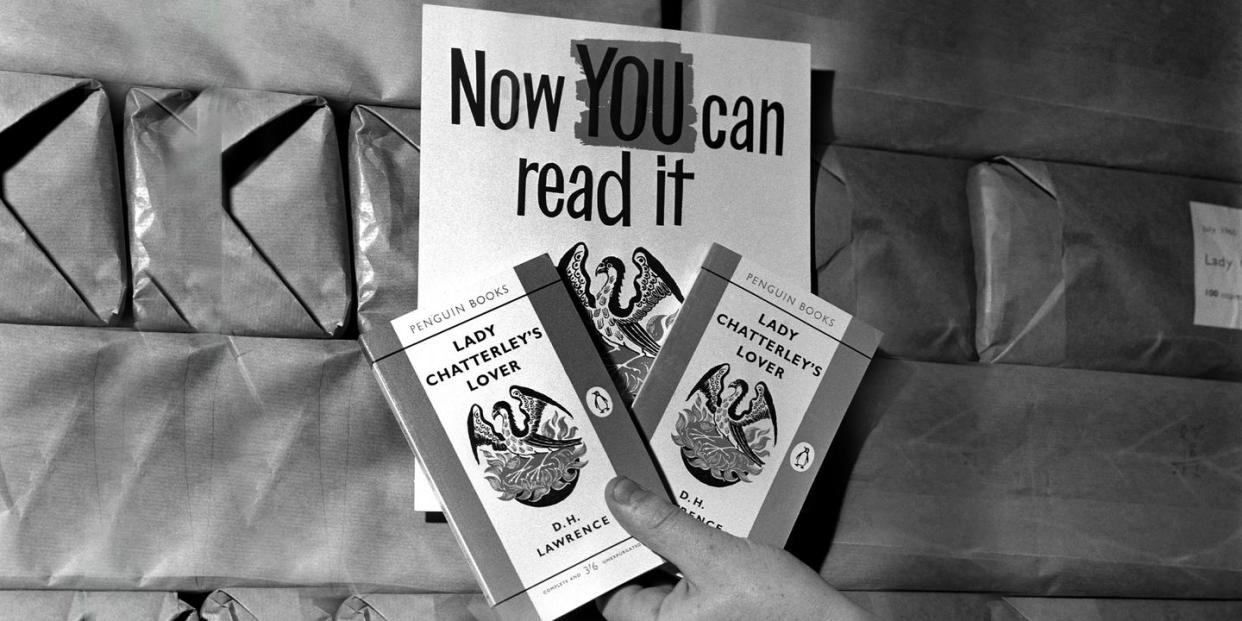

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the final novel by English author D.H. Lawrence, came into the crosshairs of the English government after it had already endured decades of scandal. Lawrence’s scorching tale of sexual and social liberation, centered on a salacious affair between an upper-class woman and her husband’s gamekeeper, had been banned (and promptly smuggled) around the world since it was first privately published in 1928. In August 1960, three decades after the author’s death, Penguin Books published the first unexpurgated English edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Then, the crackdown came—the government moved to prosecute Penguin Books under the new Obscene Publications Act of 1959, which stipulated that publishers could escape conviction by proving that their works had literary merit. “So began the mounting of the first full-scale literary trial in our legal history,” Bedford wrote. An American writer seated next to her quipped, “This is going to be the upper-middle-class English version of our Tennessee Monkey Trial.”

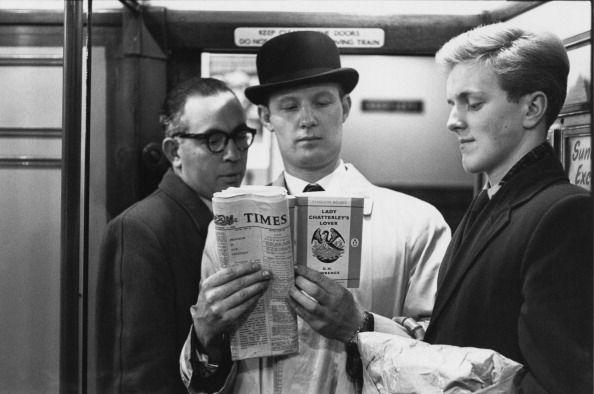

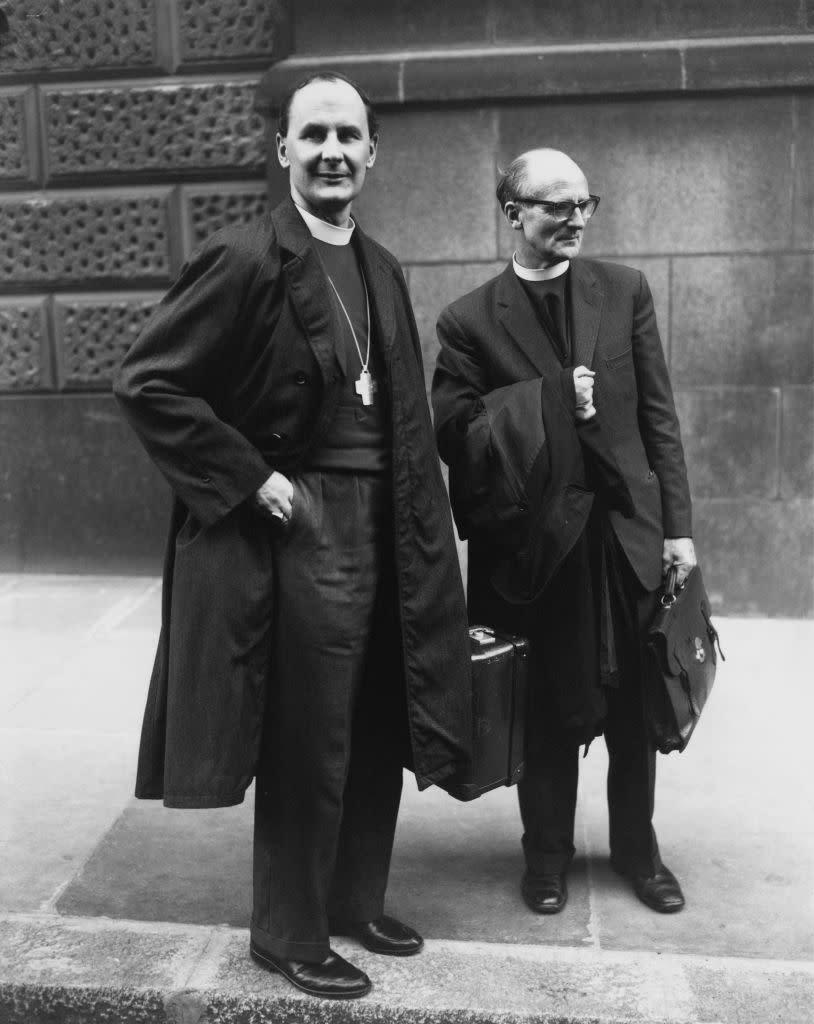

And so it was: covered breathlessly by the international media, the six-day trial featured testimony from expert witnesses including distinguished novelist E.M. Forster, a who’s who of English literati, and even a bishop, who testified that Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a book fit for Christians. Finally, after three hours of deliberation, the jury returned a unanimous verdict: Penguin Books was not guilty. A triumphant Lady Chatterley’s Lover skyrocketed to popularity, selling over three million copies in the next three months. The watershed trial has since been credited with liberalizing Britain’s cultural landscape; as barrister Geoffrey Robertson said, “No other jury verdict in British history has had such a deep social impact.”

With a new adaptation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover landing on Netflix today, as efforts to censor literature once again surge across the United States, renewed interest in the novel’s colorful history has blossomed. To break down the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Esquire Zoomed with Dr. Christopher Hilliard, a professor of history at the University of Sydney and the author of A Matter of Obscenity: The Politics of Censorship in Modern England. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: Why did the British government decide to build a case against Lady Chatterley's Lover? It seems strange that a nearly 30-year-old novel by long-dead writer would come into their crosshairs.

CHRIS HILLIARD: The book was sexually explicit and full of words that hadn’t been printed by mainstream publishers in Britain before this. When the barrister Mervyn Griffith-Jones was asked for his opinion, he said tersely, “If you don’t prosecute over this book, what are you going to prosecute over?” I think the Director of Public Prosecutions (the national chief prosecutor) decided: on the face of it, this book is obscene, and so we should make a case against it. It’s not for us to anticipate what the defense will argue—the new Obscene Publications Act puts us in new territory, and we should just make their case and let the proceedings run their course. I think it was about following process and testing the new legislation. They didn’t seem concerned about the risk of losing, whereas in other obscenity case files from the 1950s, I’ve seen prosecutors worrying about their “batting averages” (their phrase). None of the back-room lawyers were very enthusiastic or zealous about the prosecution, and the Attorney General more or less left them to it—whereas the previous year he’d gotten involved in the decision not to prosecute over Lolita. Lolita might have been an especially sensitive case because the publisher with the British rights was also a Conservative member of Parliament. (He was Harold Nicolson of Weidenfeld & Nicolson.)

Notably, Penguin priced Lady Chatterley’s Lover quite cheaply. What was the significance of that price, and how did it stack up against the price of something like Lolita?

Lolita was about twenty times more expensive than Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The publisher deliberately took that off the popular market, in a way. In those days, Penguin published original nonfiction, but otherwise, they were entirely a reprint house. When Penguin started in the 1930s, they made a big deal of saying that every book was the price of a pack of cigarettes. I can't remember what the price of cigarettes got up to in 1960, but basically, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was quite cheap and accessible.

What was the case that prosecutors sought to make against the novel? What about Lady Chatterley’s Lover was too hot to handle?

The profanities in the novel had never been published by a mainstream publisher before. The sex is explicit, and there’s also the fact that it concerns an extramarital cross-class affair. There are a lot of boundaries being crossed. But the prosecution was primarily concerned about the price. They argued, "This is going to be read by 15-year-olds who just left school going into factory jobs. Everyone will be able to buy this. It's not going to be confined to discreet readers the way Lolita was." During the trial, the prosecutor kept holding out the possibility that if they published Lady Chatterley for scholars at some higher, it'd be a different story. They argued that Penguin was basically selling pornography for the price of a pack of cigarettes.

You write that Penguin's objective was to defeat the “paternalism” of English obscenity law. Can you unpack that description?

Lady Chatterley's Lover is unusual in that it was basically always banned, whereas there were many other books containing profanity, describing sexual acts, or describing gay relationships that were never prosecuted, because they were in published in small limited editions only for the cognoscenti. Quite often, these edgy books would start with small publishers and lavish limited editions, then there would be a trade edition, and that's when the prosecution would come down. Prosecutors, police, and judges would all openly say, "This is now being offered to the general public. Anyone could read this." They were very paternalistic about this, and absolutely unashamed of it.

Going into the trial, Penguin didn’t want to make an issue of this. They wanted to make the argument that Lady Chatterley’s Lover is an important book, and it's important that people have the freedom to discuss questions about sexuality seriously. Then on day one of the trial, the prosecutor overstepped when he said, "Is this a book you wish your wife or your servants to read?" The jury laughed at him, thinking it was a sign of how out of touch he was, but in a way, he wasn’t out of touch—that paternalism is exactly what English obscenity law was. Penguin’s lawyer was told by the publisher, “Don’t go after questions of class. They’ll backfire on you. Make it about freedom, not equality.” But he sensed an opportunity to challenge this paternalism head on and ran with it.

How much attention did the trial attract during its time?

It was massive. It was very widely followed—the media couldn't resist it. Part of that was because of the Obscene Publications Act passing in 1959; the law’s main change was to make literary merit a defense, but it also enabled the defense council to call expert witnesses to say why this is good literature. Previously, any obscenity case was the prosecutor saying, "This is really bad” and the defense saying, "It's not." Then the members of the jury were given the book and told to make up their minds as to whether it was obscene or not. Because of the Obscene Publications Act, Penguin's counsel was able to turn this into a seminar about what makes literature good. They recruited famous writers from E.M. Forster downward to testify about this. Most of the establishment London press were there testifying about it. It was a real media fest, among other things.

They recruited a member of the clergy to come speak on behalf of Lady Chatterley’s Lover too, yes?

Lots of them. It was a bit of an English comedy in that way. One of them was a very influential radical Anglican who said, "Sex is holy communion." That was a gift to the prosecutor, who harassed him. Others on the bench included a monk who wrote a book about D.H. Lawrence. Because English jury deliberations are always silent and secret, we don’t know how the jury reacted to those witnesses. I wonder if part of the real purpose of calling those witnesses was not to actually persuade the jury that sex was like communion, but to create a permission structure.

If it's good enough for a priest, it's good enough for you.

The Obscene Publications Act kept the legacy definition of obscenity from the Victorian period, which was: “Is this material going to deprave and corrupt those who read it?” If a bishop says it's not going to deprave and corrupt you, that’s hard to argue with. Penguin made a very democratic argument that you should have the right to read Lady Chatterley’s Lover. You should have the right to make up your own mind, and we should all be able to talk openly about sexuality. But at the same time, there’s a bit of contradiction. They essentially said, "We want you to be free and we want to get away from paternalism. But look, we’ve got all these big-name authorities like novelists and bishops. You can take their word for it."

Why do you think the prosecution ultimately failed?

I think the prosecutor, Mervyn Griffith-Jones, ultimately overreached. I think he misread. Everyone now thinks of him as a loser because of this case, but he was a smart guy—and amazingly intimidating. He successfully prosecuted a minor Nazi propagandist at Nuremberg a couple of years after the Lady Chatterley trial. A couple of years later, at a society scandal trial, he browbeat the defendant until he actually collapsed under the strain. He was incredibly intimidating, but he blew all his credibility on day one with the line about wives and servants. It wasn’t the first time, either—there was an obscenity case in 1954, concerning a novel called The Philanderer about a New York advertising man, where he said, "Would you give this book as a Christmas present to the girls in the office?" It's bizarre. Again, there's that paternalistic aspect. He tried to play the anti-intellectual, saying things like, "It’s not really holy communion," or "Isn’t this just dressed up as highfalutin stuff?" He thought he could get away with treating the expert witnesses as eggheads or intellectuals not living in the real world. He said this incredibly paternalistic thing to the jury, but then for the rest of the trial, he tried to cozy up to the jury, essentially saying, "You and I are plain-speaking ordinary people, and all this stuff that bishops and poets are telling us is a bit over the top." He underestimated how seriously the jury would take the testimony of the expert witnesses.

How does the case still resonate with us today? Are there elements of modern life or modern law where we see its influence?

I would say no, in a way, because of the road not taken. Penguin tried to defend this on the grounds of equality, saying that poor people should be able to read the same things as rich people do. They didn’t try to defend it on the grounds of the freedom to read—that’s a very American line of defense. Gerry Gardiner, Penguin's counsel, tried to present the right to read what you want as a consumer right, whereas at the exact same time in the United States, the ACLU and a grassroots movement of librarians pushed the idea of a freedom to read. Penguin wanted to fight this on equality, saying that readers of different social origins should have the same access, rather than a generalized right to choose what they want. Ultimately, it was a big breakthrough for British freedom of speech prosecuted on the basis of equality.

You Might Also Like