Hugh Grant Talks Fascism, Bad Sex, and Being Terrified of Kate Winslet for ‘The Regime’

[Editor’s note: The following contains spoilers through Episode 4 of “The Regime.”]

Kate Winslet has only one Academy Award, but good luck telling Hugh Grant that.

More from IndieWire

Created by “Succession” writer Will Tracy, HBO’s “The Regime” is a dark political satire about an authoritarian country and its dangerously squirrely ruler. The venomous Chancellor Elena Vernham is a scene-stealing TV character who gifts Winslet ample acting opportunity.

Winslet always delivers — be it through the text-heavy speeches given to Elena’s constituency, a handful of bespoke musical theater moments (complete with flawless costumes), or the crowning jewel episode that sees Vernham meet with ex-Chancellor turned prisoner Ed Keplinger. That’s Grant.

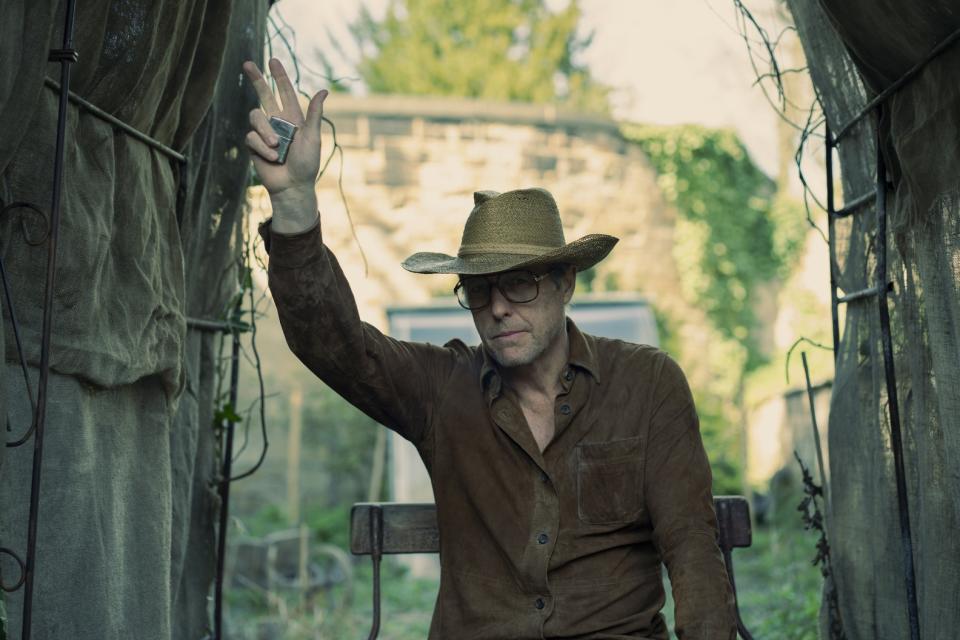

“I’ve barely seen her for 30 years since ‘Sense and Sensibility,’ and I was a bit frightened of her now,” Grant told IndieWire; he gives a shaggily chic performance as a flirty and shifty academic with a life framed in underground dystopia. “I mean, God almighty, she’s got about 400 Oscars and is revered.”

Winslet has a single Oscar win for “The Reader,” but earned her first Best Supporting Actress nomination for — you guessed it — “Sense and Sensibility.” A testament to excellence in British acting, Grant is no slouch himself. But that intimidation factor worked wonders for his second-ever production with Winslet.

Directed by Stephen Frears and fittingly written by Seth Reiss (Tracy’s co-author on the culinary thriller “The Menu”), Episode 4 “Midnight Feast” sees Vernham spiraling on the international stage before retreating to Keplinger’s dinner table in a subterranean cell. There they trade barbs about the state of their disastrous country’s government; it’s a single episode for Grant but a tension that underlies the entirety of the six-part limited series. The “Wonka” actor likened the experience to appearing opposite Meryl Streep in “Florence Foster Jenkins” and Nicole Kidman in “The Undoing.”

“I’m quite frightened of these women, so it was just a question of trying to keep my end up,” Grant said. “But when [Elena] comes to [Ed’s] cell, I know she’s going to have me beaten up because that’s what she does when she’s in a bad mood. Then about halfway through or three-quarters of the way through the scene, I just can’t stand her. And I go for her. And we go for each other.”

Talking IndieWire through his character journal from a year ago, Grant notes Winslet’s kindness in real life and breaks down his time as the late Ed Keplinger. Read on for more about the crafting of this brilliant legislative mind: a complicated fallen leader who liked schnapps, Schubert, self-governance, and sex.

“He once shagged Elena,” Grant offered. “Does that come through in that scene?”

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

IndieWire: “The Regime” and Ed Keplinger feel like such a natural fit for you given your acting and political background. Tell me about how you came by the project and your ambitions for the role.

Hugh Grant: I think Stephen Frears just sent it to me, and he has a habit of doing that out of the blue. He sends me excellent scripts. He sent me “Florence Foster Jenkins.” Then he sent me “A Very English Scandal.” And then he sent me this one and I think we have quite similar tastes. I thought, “Well, this is classy. It’s Frears. It’s Kate Winslet. It’s HBO.” And for me, it worked very well on the page. It seemed funny and cutting and sort of bonkers in a good way. And I like playing complicated, duplicitous, possibly narcissistic individuals.

I was struck by the description of Keplinger’s look as “rumpled dissident cool.” He presents right off the bat as a complete portrait. What went into your prep process creating that initial impression?

I was talking to Will Tracy about it and I can’t remember the exact conversation, but we agreed that Keplinger had probably been an academic and rather a dishy one. I think he did very well in terms of filling the seats of his lectures with that rumpled dissident charm. And on the back of that, I think he got himself up the ranks politically, came to [power], and briefly was the darling of the people. But then I think they slightly rumbled him; they slightly thought, “Hang on, maybe this guy is a bit of a narcissist. Maybe he’s not really a man of the people. Maybe all this lefty stuff is a bit of a pose.” And that was the big debate for me about the character: Did he really care about his people? Did he care about social justice or was he something of a liberal intelligencia sood?

There’s also that line, “It’s always exactly the same with you people. You refuse to choose what’s best for you.” What was your ultimate verdict with him? Was he a good guy?

I think he doesn’t really know. We didn’t really know. He’s dead now. I think it worried him. I think definitely that there had been, I would imagine, real moments of conviction. But I think like so many other people in politics, in the end, the game of politics, the snakes and ladders, becomes utterly addictive and the compulsion to win — or, in Keplinger’s case, to get revenge on Elena who has toppled him — overwhelms everything. That’s even to the point where he just can’t bear the uneducated populace who could possibly vote for this monster.

You have a reputation of engaging with tabloid press in the UK, and a big part of Keplinger’s arc is that struggle to get people to read and engage with reputable media honestly. What was it like for you to explore that frustration through a character?

Sorry, are you saying I am like Keplinger myself in my real life?

[Laughs.] No, not at all. Only in so far as you’ve had experiences talking about the way media shapes how we see things and Keplinger’s political situation is an interesting parallel.

Ah, well, it is true that I was completely uninterested in politics until I was about 50. Then I found myself swept along on this tide of campaigning about press abuse and the abuse of power in the tabloid press in the UK and in trying to get reforms enacted. I ended up meeting an awful lot of politicians and spending a lot of time campaigning and lobbying. They do sort of fascinate me. And the model of a politician who once was very passionate and full of conviction, but is now really unable to stop just thinking about themselves and their career and how can we destroy the opposition, that tribalism is a very, very, very common one — at least in the UK.

Here’s a question from my colleague, Ben Travers, who I believe you’ve spoken with for IndieWire before. He asked, “On Kate, clearly you had a bad time. Clearly she’s very hard to work with. Everyone knows. What do you need to get off your chest?”

[Chuckles.] Well, I’ve barely seen her for 30 years since “Sense and Sensibility,” and I was a bit frightened of her now. I mean, God almighty, she’s got about 400 Oscars and is revered. It was a bit like doing “Florence Foster Jenkins” with Meryl or even “The Undoing” with Nicole. I’m quite frightened of these women. So it was just a question of trying to keep my end up. She was very kind to me.

Did you have any particular moments from the script that you enjoyed?

I think that whole scene with Kate is pretty good actually. Clearly, some deal has been struck whereby [Keplinger] has to behave as this prisoner and go along with this charade of occasionally being taken to a country estate and filmed so that the population believes that he is still at large and a threat to the nation. And in return for that, I think she has promised to take care of his family who he hasn’t seen for, I’m estimating, about three years.

So, at the beginning of that scene, when she comes to my cell, I know she’s going to have me beaten up because that’s what she does when she’s in a bad mood — but I have to try and stay civil for the sake of my family. And then about halfway through or three-quarters of the way through the scene, I just can’t stand her. And I go for her. And we go for each other. I think it was very well-written. That was quite fun.

How do you think comedy and charisma play into creating those sorts of megalomaniacal characters? There’s such a great rhythm on that exchange, “I’m here to fuck your brains out, Eddie.” “Oh, right.” “That’s a joke. I’m here to smash your fucking face in.” “Well, if you think it’ll help.” Walk me through creating the tension for that type of moment; I just loved it.

Well, great! I couldn’t agree with you more. I think that’s a wonderful pair of couplets. What I’ve tried to do in my older age as an actor is not plan anything much. I do massive backstories on my character. I could tell you almost anything about his childhood or even his parents and everything. But I try not to plan the scene too much and to see what happens. Just see what happens, try and keep my ears open to what the other actor’s doing — assuming they’re any good — because that seems to be what the camera likes. I think I spent years slightly pre-planned in how I was going to deliver a line, particularly comedy lines, and I watch those things now and I think, “Yeah, that’s why that joke doesn’t work because it pre-planned, you idiot.” Whereas anything that is fresh in the moment, delivery or sometimes just an improvisation, it tends to end up in a film and it tends to work.

On the use of curse words, there’s that run you have at the end — the one that buttons the scene with Kate. Keplinger says, “They’re born in pain, so you turn their pain into anger and make their anger your cudgel. It’s brilliant, but now they’re turning the cudgel on you, aren’t they, Elena? And you know it and you’re very scared and that is why you are here. You silly fucking bitch.” Why is that little expletive at the end important?

Well, he has lost it. I mean, he’s lost his legendary self-control because he hates her so much and is so resentful of what she’s done to him and his wonderful career and his wonderful image. He just can’t fucking stand her, and his mask slips. Of course, at that moment, we know he’s going to be beaten to a jelly — and also he instantly regrets it. He says something like, “Where’s my family?” And she gives him a cryptic answer to torture him. We did try some different versions of that particular line, which were much worse than bitch.

You mentioned that you did all of this background work in terms of imagining what Keplinger’s life looked like, both as an academic but then also when he was younger. Can you tell me something that maybe didn’t make it into the show?

Funny enough, because it’s so difficult doing these interviews months and months and months after you’ve shot the thing — I mean, I shot this almost a year ago — you just can’t remember anything. So I went back and I read all my notes. I guess I could tell you he loves Schubert. His daughter is a pianist. Obviously, none of these things were ever going to end up in the show. They were never scripted; these are all just things I knew about. His mother was artistic. His father was a banker. They’re quite privileged.

What else could I tell you? He once shagged Elena. Does that come through in that scene?

[Laughs.] It does, it does.

And I think it was a failure and I think that’s one of the reasons that Keplinger is a bit obsessed with Zubak. It’s not just that he wants to deploy him, but also he’s fascinated by men who are probably better in bed than he is. I always thought Keplinger might actually be a bit lapsang souchong between the sheets.

Will Tracy and Kate spoke with me a bit about this sense that those sorts of moments of embarrassment, those innermost points of shame, get played out on a global scale through some of these moodier world leaders. What was it like to watch those little secrets you knew as an actor ramp up to meet the climactic finale we’re going to see across Episodes 5 and 6?

The shameful secret is that to this day I never read five and six and I haven’t seen them either. I’m looking forward to them. The whole thing gets broadcast next month, I think, in the UK. So that’s a treat for me. But I can’t really tell you what effect the death of Keplinger has on this story. I don’t know.

“The Regime” premiered in the U.S. on Sunday, March 3 at 9 p.m. ET on HBO. Episodes release weekly there through the Sunday, April 7 — and reach the UK Monday, April 8 on NOW TV and Sky Atlantic.

Best of IndieWire

The 12 Best Thrillers Streaming on Netflix in April, from 'Fair Play' to 'Emily the Criminal'

Quentin Tarantino's Favorite Movies: 61 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.